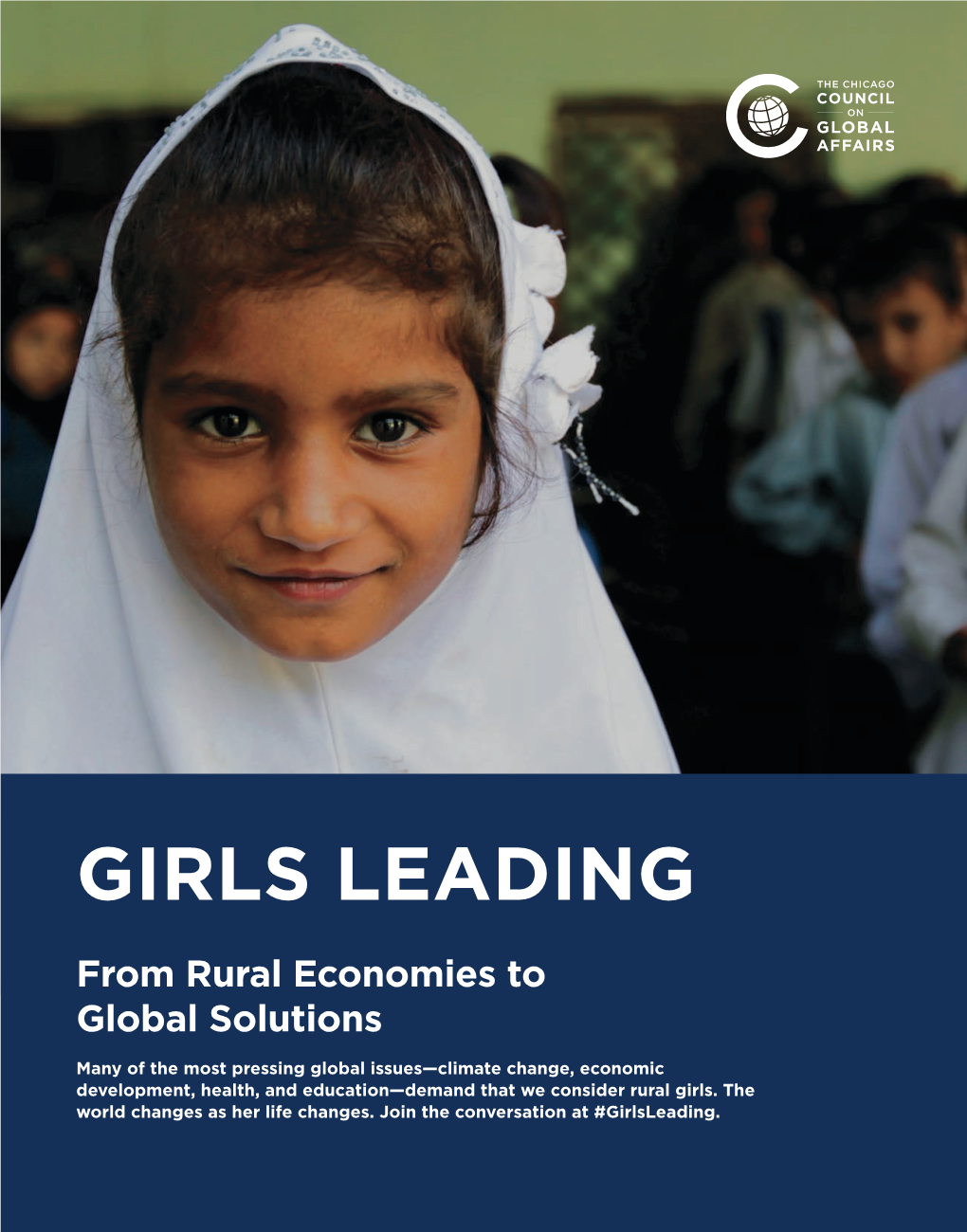

Girls Leading

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Submitted By

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by BRAC University Institutional Repository Internship Report On “Internal Investigation Practice: A Study on BRAC” Submitted to: S.M Arifuzzaman Assistant Professor, BBS, BRAC University Submitted by: Fozley Ibnul Lishan ID # 13164070 MBA, Major in Finance Date of Submission: 29th May, 2016 1 Letter of Transmittal May 29, 2016 S.M Arifuzzaman Assistant Professor, BBS, BRAC University Subject: Submission of Internship Report. Dear Sir, I, Fozley Ibnul Lishan, ID: 13164070, Major: Finance, MBA, would like to inform you that I have completed my internship report on “Internal Investigation Practice: A Study on BRAC”. In this regard I have tried my best to complete the work according to your direction. It will be great pleasure for me if kindly accept my report and allow me to complete my degree. Sincerely Yours, Fozley Ibnul Lishan ID: 13164070 MBA, Major: Finance i 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT Preparing this report the person helps me, is my coordinator, S.M Arifuzzaman whose cares make me to be served myself for making this report. And the thank goes to my colleagues who always been friendly and cooperative for putting their advices. Friends and People, who added their advices to make this report, obviously are getting worthy of thanks. In preparing this report a considerable amount of thinking and informational inputs from various sources were involved. I would like to take this opportunity to express my sincere gratitude to those without their blessing and corporation this report would not have been possible. At the very outset I would like to pay my gratitude to Almighty Allah for the kind blessing to complete the report. -

Global Philanthropy Forum Conference April 18–20 · Washington, Dc

GLOBAL PHILANTHROPY FORUM CONFERENCE APRIL 18–20 · WASHINGTON, DC 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference This book includes transcripts from the plenary sessions and keynote conversations of the 2017 Global Philanthropy Forum Conference. The statements made and views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of GPF, its participants, World Affairs or any of its funders. Prior to publication, the authors were given the opportunity to review their remarks. Some have made minor adjustments. In general, we have sought to preserve the tone of these panels to give the reader a sense of the Conference. The Conference would not have been possible without the support of our partners and members listed below, as well as the dedication of the wonderful team at World Affairs. Special thanks go to the GPF team—Suzy Antounian, Bayanne Alrawi, Laura Beatty, Noelle Germone, Deidre Graham, Elizabeth Haffa, Mary Hanley, Olivia Heffernan, Tori Hirsch, Meghan Kennedy, DJ Latham, Jarrod Sport, Geena St. Andrew, Marla Stein, Carla Thorson and Anna Wirth—for their work and dedication to the GPF, its community and its mission. STRATEGIC PARTNERS Newman’s Own Foundation USAID The David & Lucile Packard The MasterCard Foundation Foundation Anonymous Skoll Foundation The Rockefeller Foundation Skoll Global Threats Fund Margaret A. Cargill Foundation The Walton Family Foundation Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation The World Bank IFC (International Finance SUPPORTING MEMBERS Corporation) The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust MEMBERS Conrad N. Hilton Foundation Anonymous Humanity United Felipe Medina IDB Omidyar Network Maja Kristin Sall Family Foundation MacArthur Foundation Qatar Foundation International Charles Stewart Mott Foundation The Global Philanthropy Forum is a project of World Affairs. -

S-1098-0010-07-00019.Pdf

The Human Development Award A special UNDP Human Development Lifetime Achievement Award is presented to individuals who have demonstrated outstanding commitment during their lifetime to furthering the understanding and progress of human development in a national, regional or global context.This is the first time such a Lifetime Achievement Award has been awarded. Other Human Development Awards include the biennial Mahbub ul Haq Award for Outstanding Contribution to Human Development given to national or world leaders - previously awarded to President Fernando Henrique Cardoso of Brazil in 2002 and founder of Bangladesh's BRAC Fazle Hasan Abed in 2004 - as well as five categories of awards for outstanding National Human Development Reports. Human development puts people and their wellbeing at the centre of development and provides an alternative to the traditional, more narrowly focused, economic growth development paradigm. Human development is about people, about expanding their choices and capabilities to live long, healthy, knowledgeable, and creative lives. Human development embraces equitable economic growth, sustainability, human rights, participation, security, and political freedom. As part of a cohesive UN System, UNDP promotes human development through its development work on the ground in 166 countries worldwide and through the publication of annual Human Development Reports. H.M.the King of Thailand: A Lifetime of Promoting Human Development This first UNDP Human Development Lifetime Achievement Award is given to His Majesty King Bhumibol Adulyadej of Thailand for his extraordinary contribution to human development on the occasion of the sixtieth anniversary of his accession to the throne. At his coronation, His Majesty the King uttered the Oath of Accession: "We shall reign with righteousness, for the benefits and happiness of the Siamese people". -

23.11.08 the Daily Star.Pdf (89.05Kb)

Sunday, November 23, 2008 Metropolitan Make human development an enterprise of all humanity Fazle Hasan Abed says at memorial lecture DU Correspondent Make human development an enterprise of all humanity, said Fazle Hasan Abed, founder and chairperson of Brac, at a lecture in the city yesterday. “We must take up every acceptable implement- whether social, legal, scientific, economic or political- to make human development the enterprise of all humanity,” he added. Abed was delivering the Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed Memorial Lecture 2008 on the 'Development as a Right: The Role of Legal Empowerment in the Making of a Just Society' at the National Museum auditorium. It was organised by Barrister Syed Ishtiaq Ahmed Memorial Foundation at the Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. “When a single member of our neighbourhood lives in poverty and squalor, we are all impoverished,” he said. It is for the governments, organisations and individuals who should practise as a daily act of social justice to make the society a just one, he observed. The Brac founder said in an unequal society where the poor are already disadvantaged, it is important to provide legal safety nets before allowing market forces to operate freely. The present global financial crisis is an example of the unfair economic and social policies at work, he added. Abed said issues like sustainable development, responsible energy, carbon trading or water foot- printing, in the case of Bangladesh, have direct bearing on imminent challenges on several fronts, particularly in food security and climate changes. "It is a sad reality that globally as well as nationally, we have had to wait for such grim realities to shake us out of our self-absorbed comfort zones and make us connect the crucial dots between our rights, needs and responsibilities to our respective societies," he added. -

Women, Business and the Law 2020 World Bank Group

WOMEN, BUSINESS AND THE LAW 2020 AND THE LAW BUSINESS WOMEN, WOMEN, BUSINESS AND THE LAW 2020 WORLD BANK GROUP WORLD WOMEN, BUSINESS AND THE LAW 2020 © 2020 International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank 1818 H Street NW, Washington, DC 20433 Telephone: 202-473-1000; Internet: www.worldbank.org Some rights reserved 1 2 3 4 23 22 21 20 This work is a product of the staff of The World Bank with external contributions. The findings, interpretations, and conclusions expressed in this work do not necessarily reflect the views of The World Bank, its Board of Executive Directors, or the govern- ments they represent. The World Bank does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this work. The boundaries, colors, denominations, and other information shown on any map in this work do not imply any judgment on the part of The World Bank concerning the legal status of any territory or the endorsement or acceptance of such boundaries. Nothing herein shall constitute or be considered to be a limitation upon or waiver of the privileges and immunities of The World Bank, all of which are specifically reserved. Rights and Permissions This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 IGO license (CC BY 3.0 IGO) http://creativecommons.org/ licenses/by/3.0/igo. Under the Creative Commons Attribution license, you are free to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt this work, including for commercial purposes, under the following conditions: Attribution—Please cite the work as follows: World Bank. 2020. Women, Business and the Law 2020. -

30 November 2011 Berlin, Dhaka Friends: Wulff

PRESSE REVIEW Official visit of German Federal President in Bangladesh 28 – 30 November 2011 Bangladesh News 24, Bangladesch Thursday, 29 November 2011 Berlin, Dhaka friends: Wulff Dhaka, Nov 29 (bdnews24.com) – Germany is a trusted friend of Bangladesh and there is ample scope of cooperation between the two countries, German president Christian Wulff has said. Speaking at a dinner party hosted by president Zillur Rahman in his honour at Bangabhaban on Tuesday, the German president underlined Bangladesh's valuable contribution to the peacekeeping force. "Bangladesh has been one of the biggest contributors to the peacekeeping force to make the world a better place." Prime minister Sheikh Hasina, speaker Abdul Hamid, deputy speaker Shawkat Ali Khan, ministers and high officials attended the dinner. Wulff said bilateral trade between the two countries is on the rise. On climate change, he said Bangladesh should bring its case before the world more forcefully. http://bdnews24.com/details.php?id=212479&cid=2 [02.12.2011] Bangladesh News 24, Bangladesch Thursday, 29 November 2011 'Bangladesh democracy a role model' Bangladesh can be a role model for democracy in the Arab world, feels German president. "You should not mix religion with power. Tunisia, Libya, Egypt and other countries are now facing the problem," Christian Wulff said at a programme at the Dhaka University. The voter turnout during polls in Bangladesh is also very 'impressive', according to him. The president came to Dhaka on a three-day trip on Monday. SECULAR BANGLADESH He said Bangladesh is a secular state, as minority communities are not pushed to the brink or out of the society here. -

The World's 500 Most Influential Muslims, 2021

PERSONS • OF THE YEAR • The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • B The Muslim500 THE WORLD’S 500 MOST INFLUENTIAL MUSLIMS • 2021 • i The Muslim 500: The World’s 500 Most Influential Chief Editor: Prof S Abdallah Schleifer Muslims, 2021 Editor: Dr Tarek Elgawhary ISBN: print: 978-9957-635-57-2 Managing Editor: Mr Aftab Ahmed e-book: 978-9957-635-56-5 Editorial Board: Dr Minwer Al-Meheid, Mr Moustafa Jordan National Library Elqabbany, and Ms Zeinab Asfour Deposit No: 2020/10/4503 Researchers: Lamya Al-Khraisha, Moustafa Elqabbany, © 2020 The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre Zeinab Asfour, Noora Chahine, and M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin 20 Sa’ed Bino Road, Dabuq PO BOX 950361 Typeset by: Haji M AbdulJaleal Nasreddin Amman 11195, JORDAN www.rissc.jo All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced or utilised in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanic, including photocopying or recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Views expressed in The Muslim 500 do not necessarily reflect those of RISSC or its advisory board. Set in Garamond Premiere Pro Printed in The Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan Calligraphy used throughout the book provided courte- sy of www.FreeIslamicCalligraphy.com Title page Bismilla by Mothana Al-Obaydi MABDA • Contents • INTRODUCTION 1 Persons of the Year - 2021 5 A Selected Surveyof the Muslim World 7 COVID-19 Special Report: Covid-19 Comparing International Policy Effectiveness 25 THE HOUSE OF ISLAM 49 THE -

The Blended Value Map Annotated Bibliography

The Blended Value Map Annotated Bibliography 1 Introductory Note: Please note, this document is meant to accompany The Blended Value Map. The descriptions of organizations and resources in this document are primarily drawn directly from the relevant websites. When another website or document is the source, the link or reference is provided. The descriptions in this document are not meant to be definitive, we recommend readers go directly to the source material or website listed for more definitive material. 2 Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) General Overview 3 Information Resources (Books, Articles, Websites) Business for Social Responsibility Website www.bsr.org white papers Business for Social Responsibility (BSR) is a global organization that helps member companies achieves success in ways that respect ethical values, people, communities and the environment. BSR provides information, tools, training and advisory services to make corporate social responsibility an integral part of business operations and strategies. A nonprofit organization, BSR promotes cross sector collaboration and contributes to global efforts to advance the field of corporate social responsibility. www.bsr.org AtKisson Accelerator Sustainability Tool Kit The AtKisson Accelerator (trademarks and registrations pending) is a comprehensive toolkit that helps integrate sustainability into organizations, initiatives, and plans. It is for use by any group, organization, business, community, or region, in virtually any context. The purpose is to help those initiatives -

TECHNOLOGY and INNOVATION REPORT 2021 Catching Technological Waves Innovation with Equity

UNITED NATIONS CONFERENCE ON TRADE AND DEVELOPMENT TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION REPORT 2021 Catching technological waves Innovation with equity Geneva, 2021 © 2021, United Nations All rights reserved worldwide Requests to reproduce excerpts or to photocopy should be addressed to the Copyright Clearance Center at copyright.com. All other queries on rights and licences, including subsidiary rights, should be addressed to: United Nations Publications 405 East 42nd Street New York, New York 10017 United States of America Email: [email protected] Website: https://shop.un.org/ The designations employed and the presentation of material on any map in this work do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. This publication has been edited externally. United Nations publication issued by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development. UNCTAD/TIR/2020 ISBN: 978-92-1-113012-6 eISBN: 978-92-1-005658-8 ISSN: 2076-2917 eISSN: 2224-882X Sales No. E.21.II.D.8 ii TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION REPORT 2021 CATCHING TECHNOLOGICAL WAVES Innovation with equity NOTE Within the UNCTAD Division on Technology and Logistics, the STI Policy Section carries out policy- oriented analytical work on the impact of innovation and new and emerging technologies on sustainable development, with a particular focus on the opportunities and challenges for developing countries. It is responsible for the Technology and Innovation Report, which seeks to address issues in science, technology and innovation that are topical and important for developing countries, and to do so in a comprehensive way with an emphasis on policy-relevant analysis and conclusions. -

Towards a More Reliable and Caring City

Nalalaoman | Nasasarigan | Nangangataman VOLUME 1 - NO. 1 JULY - OCTOBER 2019 TOWARDS A MORE RELIABLE AND CARING CITY OF MAYOR NELSON S. LEGACION PB 2019 FIRST 100 DAYS BY MAYOR SON 1 GREENER CITY OF NAGA Balatas Open Dumpsite, Naga City 2 2019 FIRST 100 DAYS BY MAYOR SON 3 GREENER CITY OF NAGA REFLECTING MAYOR SON’S VISION OF GREEN, mini-forests inside Naga’s urban areas, the Forests-in-our-Midst (FOM) Program was launched at the former Balatas Open Dumpsite area where 1,500 native trees were planted as a forest-growing activity, launching the start of the city’s plan towards a greener Naga. 2 2019 FIRST 100 DAYS BY MAYOR SON 3 ContentNagas Na! 06 PUTTING THE HOUSE IN ORDER 20 TECH4ED PROJECT: DIGITAL EMPOWERMENT ‘NAGA NA!’: NEW CITY BRAND MODERNIZING THE 07 21 BICOL CENTRAL STATION INTERNET ACCESSIBILITY: 21 FREE PUBLIC WIFI 22 NEW INFIRMARY LABORATORY 23 ADDITIONAL MEDICAL PERSONNEL PUBLIC TOILETS FOR MALE, 23 FEMALE, AND LGBTQ+ COMMUNITY MEETINGS: TO BE CONSTRUCTED 07 DRAWING NEARER TO THE PEOPLE MORE CLASSROOMS, 24 MORE SCHOLARS 10 ACCESSIBLE CITY HALL CULTURE OF SPORTS EXCELLENCE BALATAS OPEN 25 12 DUMPSITE CLOSURE MAKING A NAME IN THE 26 INTERNATIONAL ARENA NEWLY-OPENED SLF PROVIDES 13 THE OPTION OF CONVERTING OUR GARBAGE INTO ENERGY STRENGTHENING INTERNATIONAL 27 LINKAGES: CULTURAL AND ECONOMIC TIES WITH CZECH FOREST IN OUR MIDST: REPUBLIC 14 NAGA GREENING MISS EARTH FLORA 2019 IN NAGA 15 CITY PLASTIC REGULATION 28 ROAD TO PUBLIC SAFETY: SALARY ADJUSTMENT FOR CITY 16 ROAD CLEARING OPERATIONS 29 HALL JOB ORDER AND CONTRACT- OF-SERVICE EMPLOYEES LIGHTS AND CAMERAS: 17 PRELUDE TO A SAFER NAGA 29 IMPROVED LEGAL SERVICES DRAINAGE MASTERPLAN: 17 SOLVING THE CITY FLOODING NAGA NA! PRELIMINARY STEPS IN BOOSTING NAGA’S TOURISM AND HOUSING SOLUTIONS 30 18 LOCAL ECONOMY 20 MAKING A BIG DIGITAL LEAP PEÑAFRANCIA 2019 COMMITTEE CHAIRMANSHIPS & MEMBERSHIPS MYC 2019: ANCHORING 34 THE FAITH OF THE YOUTH HON. -

Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia

Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Edited by Halim Rane Printed Edition of the Special Issue Published in Religions www.mdpi.com/journal/religions Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia Editor Halim Rane MDPI • Basel • Beijing • Wuhan • Barcelona • Belgrade • Manchester • Tokyo • Cluj • Tianjin Editor Halim Rane Centre for Social and Cultural Research / School of Humanities, Languages and Social Science Griffith University Nathan Australia Editorial Office MDPI St. Alban-Anlage 66 4052 Basel, Switzerland This is a reprint of articles from the Special Issue published online in the open access journal Religions (ISSN 2077-1444) (available at: www.mdpi.com/journal/religions/special issues/ Australia muslim). For citation purposes, cite each article independently as indicated on the article page online and as indicated below: LastName, A.A.; LastName, B.B.; LastName, C.C. Article Title. Journal Name Year, Volume Number, Page Range. ISBN 978-3-0365-1222-8 (Hbk) ISBN 978-3-0365-1223-5 (PDF) © 2021 by the authors. Articles in this book are Open Access and distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license, which allows users to download, copy and build upon published articles, as long as the author and publisher are properly credited, which ensures maximum dissemination and a wider impact of our publications. The book as a whole is distributed by MDPI under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons license CC BY-NC-ND. Contents About the Editor .............................................. vii Preface to ”Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia” ........................ ix Halim Rane Introduction to the Special Issue “Islamic and Muslim Studies in Australia” Reprinted from: Religions 2021, 12, 314, doi:10.3390/rel12050314 .................. -

Gob. Murphy Flexibiliza Restricciones Por COVID-19

Senadores Instan al Presidente Biden Enfocarse en Acceso a Vacunas COVID-19 para... Latinoaméricadental, instaron hoy a la Administración Bi - aproximadamente un tercio de la cifra total de Por Abel Berry Especial para LA VOZ) den a que desarrolle una estrategia integral muertos a nivel mundial a consecuencia del WASHINGTON – El Senador Bob Me - que aborde la grave crisis del COVID-19 en COVID-19. néndez (D-N.J.), el Presidente del Comité de América Latina y el Caribe y se enfoque en el “Es crítico que los Estados Unidos expanda Relaciones Exteriores en el Senado, y los acceso a vacunas para los países en desarrollo nuestros esfuerzos para asegurar que las per- Senadores Tim Kaine (D-Va.) y Marco Rubio en las Américas. Mientras la pandemia con- sonas más vulnerables del mundo sean vacu- (R-Fla.), el Presidente y Miembro de Más Alto tinua arrasando varios países de la región, nadas”, escribieron los senadores al Presidente Rango del Subcomité del Hemisferio Occi - AméricaQQQQ¢¢¢¢ Latina y QQQQ¢¢¢¢el Caribe ya constituyenQQQ¢¢¢QQQQQ¢¢¢¢¢QQQQ¢¢¢¢(Pasa a la Página 15) Gob. Murphy Flexibiliza Restricciones por COVID-19 (Vea la Página 12) Marisa Butler de Estados Unidos Coronada en el Miss Earth 2021 QQQQ¢¢¢¢QQQQ¢¢¢¢QQQ¢¢¢QQQQQ¢¢¢¢¢QQQQ¢¢¢¢ VOCERO HISPANO DE NEW JERSEY AÑO XLVII 20 DE MAYO DE 2021 QQQQ¢¢¢¢ConmemoranQQQQ¢¢¢¢ en NewarkQQQ¢¢¢ FechaQQQQQ¢¢¢¢¢ Patria delQQQQ¢¢¢¢ 20 de Mayo En conmemoración a la fecha Patria del 20 de Mayo y el Apóstol de Cuba José Martí, en el aniversario de su muerte, el pasado domingo en la ciudad de Newark se llevó a cabo una ceremonia en el Mother Cabrini Park, localizado en la calle Market detrás de la Penn Station, que incluyó la entonación de los himnos cubano y americano, una ofrenda floral ante el Busto del Apóstol y el uso de la palabra de prominentes figuras de la comunidad.