The New Jacob Bronowski Archive Erica Wagner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

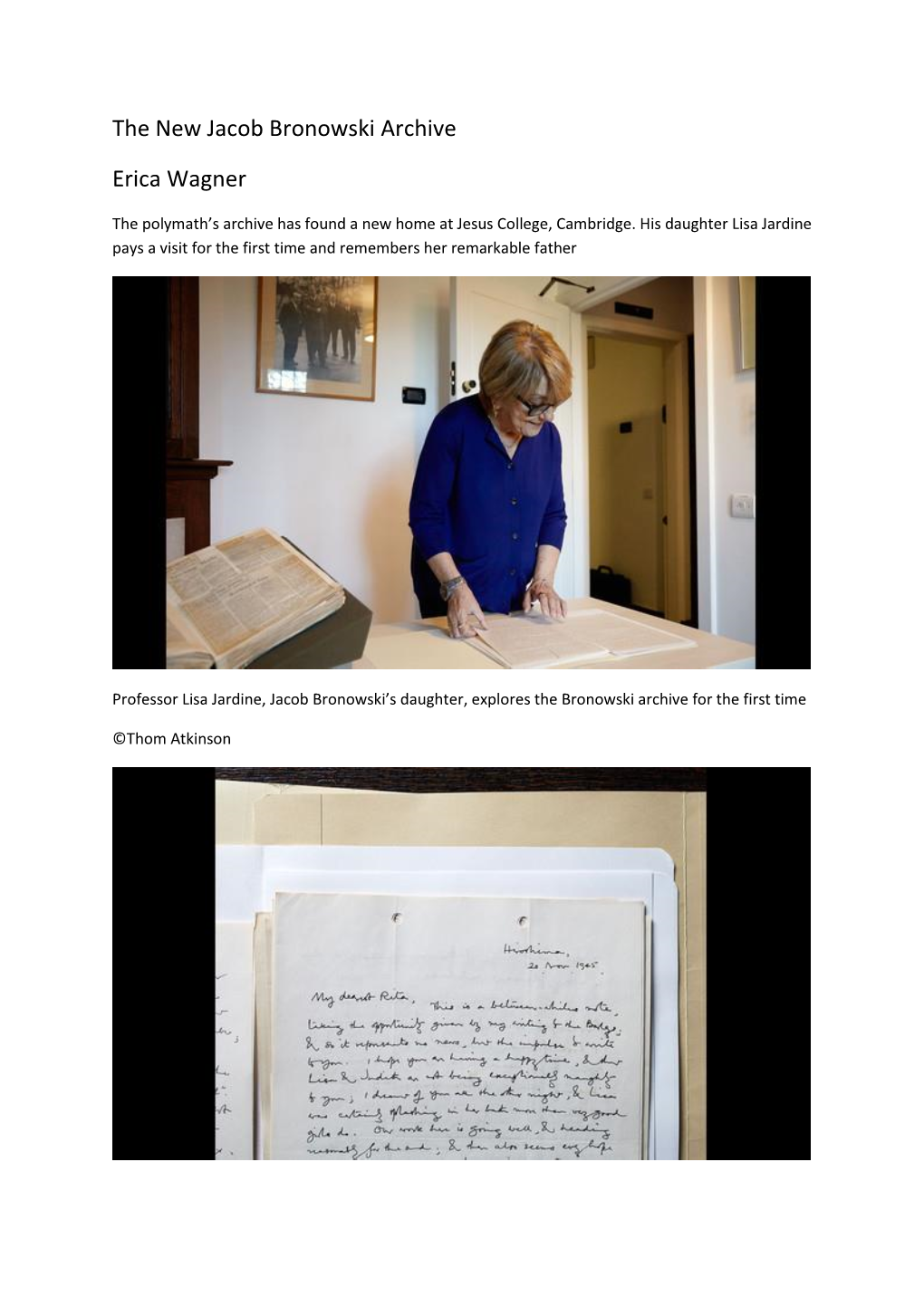

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Full List of Files Released L C P First Date Last Date Scope/Content

Full list of files released L C P First Date Last Date Scope/Content Former Ref Note KV 2 WORLD WAR II KV 2 German Intelligence Agents and Suspected Agents KV 2 3386 06/03/1935 18/08/1953 Greta Lydia OSWALD: Swiss. Imprisoned in PF 45034 France on grounds of spying for Germany in 1935, OSWALD was said to be working for the Gestapo in 1941 KV 2 3387 12/11/1929 12/01/1939 Oscar Vladimirovich GILINSKY alias PF 46098 JILINSKY, GILINTSIS: Latvian. An arms dealer VOL 1 in Paris, in 1937 GILINSKY was purchasing arms for the Spanish Popular Front on behalf of the Soviet Government. In November 1940 he was arrested by the Germans in Paris but managed to obtain an exit permit. He claimed he achieved this by bribing individual Germans but, after ISOS material showed he was regarded as an Abwehr agent, he was removed in Trinidad from a ship bound for Buenos Aires and brought to Camp 020 for interrogation. He was deported in 1946 KV 2 3388 13/01/1939 16/02/1942 Oscar Vladimirovich GILINSKY alias PF 46098 JILINSKY, GILINTSIS: Latvian. An arms dealer VOL 2 in Paris, in 1937 GILINSKY was purchasing arms for the Spanish Popular Front on behalf of the Soviet Government. In November 1940 he was arrested by the Germans in Paris but managed to obtain an exit permit. He claimed he achieved this by bribing individual Germans but, after ISOS material showed he was regarded as an Abwehr agent, he was removed in Trinidad from a ship bound for Buenos Aires and brought to Camp 020 for interrogation. -

Notes to Robert Curtis's Presentation at WL2018

Notes to Robert Curtis's presentation at WL2018 R. T. Curtis Some students of H.F. Baker Henry Frederick Baker was a hugely influential Cambridge geometer in the late 19th and early 20th century. His students included Coxeter who went on to become one of the most important geometers in the 20C; du Val and Edge, who were distinguished algebraic ge- ometers; and Todd of the Todd-Coxeter coset enumeration algorithm. The eminent number theorist Mordell was another student, as was Jacob Bronowski who wrote and presented The Ascent of Man which in the 1960s was a popular television series about the rise of civilization. Bronowski's daughter Lisa (later Lisa Jardine) also studied Mathematics at Cambridge in the year above me but changed to English in her third year and went on to become Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary, University of London. This talk will begin with the contribution of Todd. The synthematic totals preserved by the symmetric group S6 The 15 partitions of six letters into pairs are known as synthemes; a set of five synthemes such that every pair appears is a synthematic total; there are just 6 of these totals, and so the symmetric group S6 permutes both the original 6 letters and the 6 totals. Todd wrote the totals on the board in his 1967 Cambridge Part III course which I attended, and demonstrated important properties of these two non-permutation identical actions. From S6 to M12 to M24 Todd's lectures demonstrated an important method of constructing groups: Use a well- known group to construct a new combinatorial or geometric structure; observe that the new structure possesses more symmetries than just the group you used in its construction. -

AUTOBIOGRAPHY and HISTORY on SCREEN: the Life and Times of Lord

AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND HISTORY ON SCREEN: The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten 1 Abstract: The television series, The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten (1968), was a unique collaboration between an independent production company, Associated- Rediffusion, a national museum, the Imperial War Museum, and one of the most famous aristocratic and military figures of the 20th century, Lord Mountbatten. Furthermore, Mountbatten was the programme’s presenter, appearing on screen to describe his experiences autobiographically. Through the use of film and images, Mountbatten’s ‘life’ was intertwined with the historical ‘times’ of over half a century. Though praised at the point of its release to British audiences in 1969 by the public, critics and historians alike, The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten has since largely been ignored by scholars interested in the history-on-television genre. By detailing the origins, format, production and reception of the series, and by comparing it to both The Great War (1964) and The World at War (1973-1974), which were also produced in conjunction with the Imperial War Museum, the immediate success and subsequent failure of The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten to attract popular and academic attention provides an argument for widening the discussion on television history and its limited categorizations. Key words: autobiography, history, television, Imperial War Museum, The Great War, The World at War. 2 To tell the story of this century on television is in itself a formidable task. To focus this story on one single man, however remarkable his career, breaks new ground. This series is not only about Lord Mountbatten, it is with him and that gives this television history a unique dimension.1 Academic literature concerning factual history programmes is abundant with references to The Great War and The World at War, which were television series made in collaboration with the Imperial War Museum (IWM) from 1963-1964 and 1971-1974 respectively. -

Science, Scientific Intellectuals and British Culture in the Early Atomic Age, 1945-1956: a Case Study of George Orwell, Jacob Bronowski, J.G

Science, Scientific Intellectuals and British Culture in The Early Atomic Age, 1945-1956: A Case Study of George Orwell, Jacob Bronowski, J.G. Crowther and P.M.S. Blackett Ralph John Desmarais A Dissertation Submitted In Fulfilment Of The Requirements For The Degree Of Doctor Of Philosophy Imperial College London Centre For The History Of Science, Technology And Medicine 2 Abstract This dissertation proposes a revised understanding of the place of science in British literary and political culture during the early atomic era. It builds on recent scholarship that discards the cultural pessimism and alleged ‘two-cultures’ dichotomy which underlay earlier histories. Countering influential narratives centred on a beleaguered radical scientific Left in decline, this account instead recovers an early postwar Britain whose intellectual milieu was politically heterogeneous and culturally vibrant. It argues for different and unrecognised currents of science and society that informed the debates of the atomic age, most of which remain unknown to historians. Following a contextual overview of British scientific intellectuals active in mid-century, this dissertation then considers four individuals and episodes in greater detail. The first shows how science and scientific intellectuals were intimately bound up with George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty Four (1949). Contrary to interpretations portraying Orwell as hostile to science, Orwell in fact came to side with the views of the scientific rig h t through his active wartime interest in scientists’ doctrinal disputes; this interest, in turn, contributed to his depiction of Ingsoc, the novel’s central fictional ideology. Jacob Bronowski’s remarkable transition from pre-war academic mathematician and Modernist poet to a leading postwar BBC media don is then traced. -

The Routledge Companion to British Media History

40 The origins and practice of science on British television Timothy Boon and Jean-Baptiste Gouyon Both science and television have been extraordinarily powerful forces for economic, social and cultural change in the period since 1945. It follows that the television representation of scientific and technological subjects should be an exceptionally potent subject for revealing core elements of our culture. And yet science television has until recently been the province of a very small coterie of scholars. As a result, what we know about the story of the history of science on television is uneven. However, especially in a volume of this breadth, where it is possible to draw comparison with other fields, it is important to ask what it has meant, over the substantive period of British television history, to present science, specifically on television. But we must work with what we have, and this essay follows the weight of the literature in covering the period before 1980 in significantly more depth than the last few decades. What has it meant to viewers to experience science television programs? The fundamental point about the history, institutions and influence of television is that it was the growth of viewers that drove its development. Television license holders increased 300-fold in the key years of expansion between 1947 and 1955, by which date 4.5 million homes had sets; there were 13 million by 1964 when BBC2 started; in 2009–10, 25 million licenses were in force. All the same, it is difficult to make direct links between these bald figures and the experience of viewers of science television programs. -

Bronowski: the Complex Life of a Science Popularizer David Edgerton Parses a Biography of a Polymath and Star of 1970S Broadcasting

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS SCIENCE ENGAGEMENT Bronowski: the complex life of a science popularizer David Edgerton parses a biography of a polymath and star of 1970s broadcasting. or millions of people in the 1970s, the name Jacob Bronowski was synony- mous with science. The Polish-born Fmathematician arrived in London in 1920, at the age of 12. More than half a century later, his finest hour came with the 1973 television series The Ascent of Man, made by the BBC. EVERETT COLLECTION/ALAMY EVERETT Aiming to trace what art historian Kenneth Clark did not in his 1969 series Civilisation, Bronowski’s programme was a long look at the development of society through a scien- tific lens. It was followed that year by a book of the same name. Now, Timothy Sandefur, an adjunct scholar at the libertarian think tank the Cato Institute in Washington DC, makes great claims in The Ascent of Jacob Bronowski. Sandefur describes him as more than a mere polymath, suggesting that he “was involved with nearly every major intellectual under- taking of the twentieth century”; that he was a “serious philosopher” who made “probably the finest documentary film ever made”. Up to a point. There were more Renais- sance men (and inequality meant that all too many were men) in the twentieth cen- tury than one can shake one’s specialist fist at. Just among British mathematician- philosophers, Bertrand Russell and Alfred North Whitehead were more significant in both fields than Bronowski. Chem- ist Michael Polanyi’s philosophical works, notably Personal Knowledge (1958), were in a different league from Bronowski’s mushy apologias, such as The Common Sense of Science (1951). -

Geometry at Cambridge, 1863–1940 ✩

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Elsevier - Publisher Connector Historia Mathematica 33 (2006) 315–356 www.elsevier.com/locate/yhmat Geometry at Cambridge, 1863–1940 ✩ June Barrow-Green, Jeremy Gray ∗ Centre for the History of the Mathematical Sciences, Faculty of Mathematics and Computing, The Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK Available online 10 January 2006 Abstract This paper traces the ebbs and flows of the history of geometry at Cambridge from the time of Cayley to 1940, and therefore the arrival of a branch of modern mathematics in Great Britain. Cayley had little immediate influence, but projective geometry blossomed and then declined during the reign of H.F. Baker, and was revived by Hodge at the end of the period. We also consider the implications these developments have for the concept of a school in the history of mathematics. © 2005 Published by Elsevier Inc. Résumé L’article retrace les hauts et le bas de l’histoire de la géométrie à Cambridge, du temps de Cayley jusqu’à 1940. Il s’agit donc de l’arrivée d’une branche de mathématiques modernes en Grande-Bretagne. Cayley n’avait pas beaucoup d’influence directe, mais la géométrie projective fut en grand essor, déclina sous le règne de H.F. Baker pour être ranimée par Hodge vers la fin de notre période. Nous considérons aussi brièvement l’effet que tous ces travaux avaient sur les autres universités du pays pendant ces 80 années. © 2005 Published by Elsevier Inc. MSC: 01A55; 01A60; 51A05; 53A55 Keywords: England; Cambridge; Geometry; Projective geometry; Non-Euclidean geometry ✩ The original paper was given at a conference of the Centre for the History of the Mathematical Sciences at the Open University, Milton Keynes, MK7 6AA, UK, 20–22 September 2002. -

HRI# ___PRIMARY RECORD Trino

State of California -The Resources Agency Primary#------ DEPARTMENT OF PARKS AND RECREATION HRI# _________ PRIMARY RECORD Trinomial _______ NRHP Status Code 552 Other Listings ---------------------- Review Code Reviewer Date. _ _ _ *Page 1 of 26 *Resource Name or#: 9438 La Jolla Farms Road. La Jolla. CA 92037 *Pl. Other Identifier: Jacob and Rita Bronowski Residence *PZ: Location: Not for publicat ion Unrestricted ~ a. County: San Diego And (P2b and P2c or P2d. Attach a location map as necessary.) *b. USGS Quad La Jolla *Date: 1996 T; R; r.i of~ of Sec.__ B.M. ______ c. Address: 9438 La Jolla Farms Road City: San Diego Zip: 92037 d. UTM: (Give more than one large or linear resources) Zone: Me/ mN e. Other Locational Data (e.g. parcel#, directions to resource, elevation, etc. as appropriate); APN: #342-091-04, Lot 24, La Jolla Farms, Map No. 3487 *P3a. Description (Describe resource and its major elements, include design, materials, condition, alterations, size, setting and boundaries.) The resource is a one-story, basically rectangular shaped, asymmetrical, 20th Century Modern, International style, single family residence. The structure is located on a large lot in an upscale residential community in La Jolla. The building is sited on a bluff overlooking the Pacific Ocean. The front portion of the property contains a long driveway leading to the structure but little formal landscaping. The building has a concrete foundation, stucco exterior and a flat roof. The east fa~ade contains the main entrance to the structure and faces the street. The fa~ade is painted stucco. -

Humanist Blockbuster: Jacob Bronowski and the Ascent of Man Hall, Alexander

University of Birmingham A Humanist Blockbuster: Jacob Bronowski and The Ascent of Man Hall, Alexander DOI: 10.2307/j.ctvqc6h4s License: Unspecified Document Version Peer reviewed version Citation for published version (Harvard): Hall, A 2019, A Humanist Blockbuster: Jacob Bronowski and The Ascent of Man. in Rethinking History, Science, and Religion: An Exploration of Conflict and the Complexity Principle. University of Pittsburgh Press, pp. 145- 159. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvqc6h4s Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. When citing, please reference the published version. Take down policy While the University of Birmingham exercises care and attention in making items available there are rare occasions when an item has been uploaded in error or has been deemed to be commercially or otherwise sensitive. -

A Complete Bibliography of Publications of John Von Neumann

A Complete Bibliography of Publications of John von Neumann Nelson H. F. Beebe University of Utah Department of Mathematics, 110 LCB 155 S 1400 E RM 233 Salt Lake City, UT 84112-0090 USA Tel: +1 801 581 5254 FAX: +1 801 581 4148 E-mail: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] (Internet) WWW URL: http://www.math.utah.edu/~beebe/ 09 March 2021 Version 1.199 Abstract This bibliography records publications of John von Neumann (1903– 1957). Title word cross-reference 1 + 2 [vN51c]. $125 [Lup03]. $19.95 [Kev81]. 2; 000 [MRvN50]. $23.00 [MC00]. $25.00 [Jon04]. $29.95 [CK12]. 21=3 [vNT55]. $35.00 [Ano91, Pan92]. $37.50 [Ano91]. $45.00 [Ano91]. e [MRvN50, Rei50]. F∞ [vN62]. H [vN29b, von10]. N [vN46b]. ν [vN62]. p [DJ13]. p = Kρ4=3 ρ [vNxxb]. π [MRvN50, Rei50, She12]. q [DJ13]. Tρ = 0 [vN35h]. -theorem [von10]. -Theorems [vN29b]. /119.00 [Emc02]. /89.00 [Emc02]. 1 2 0 [Lup03, MC00, Rec07]. 0-19-286162-X [Twe93]. 0-201-50814-1 [Ano91]. 0-262-01121-2 [Ano91, Bow92]. 0-262-12146-8 [Ano91]. 0-262-16123-0 [Ano91]. 0-521-52094-0 [Jon04]. 0-7923-6812-6 [Emc02, Lup03]. 0-8027-1348-3 [MC00]. 0-8218-3776-1 [Rec07]. 1 [GvN47b, GvN47c, GvN47d, Rec07, vNW28a]. 10/18/51 [McC83]. 12th [Var88, Wah96]. 1900s [IM95]. 1927 [Has10a]. 1940s [IM09a]. 1942-1952 [Fit13]. 1946 [vN57b]. 1949 [Ano51]. 1950s [IM09a, Mah11]. 1954 [R´ed99]. 1957 [Ano57c, OPP58, Tel57, Wig57, Wig67a, Wig67c, Wig80]. 1981 [Bir83]. 1982 [TWA+87]. 1988 [B+89, GIS90, Var88]. -

Percy and Sagan in the Cosmos | Books and Culture 2/20/20, 5:58 PM

Percy and Sagan in the Cosmos | Books and Culture 2/20/20, 5:58 PM Print this page Close this page The following article is located at: https://www.booksandculture.com/articles/2013/marapr/percy-and-sagan-in-cosmos.html Percy and Sagan in the Cosmos On the 30th anniversary of "The Last Self-Help Book." Alan Jacobs | posted 3/04/2013 It is February of 1969 and a new television series is beginning on BBC2. The first images—they are in color, which is noteworthy—are of Michaelangelo's David, Botticelli's Primavera (in closeup), a series of beautiful buildings both ancient and modern. A noble and passionate organ piece by Bach plays. Finally one word appears on the screen: "CIVILISATION"—followed soon by this: "A Personal View by Kenneth Clark." In weekly episodes that last into May, the learned and patrician Clark, one of the great art historians of his age, guides his viewers through the history of European art from the fall of Rome to the rise of modernist architecture in the New World. In the first sentence he speaks, Clark quotes John Ruskin's view that it is through the history of art that we can best understand a given civilization's core commitments and true achievements; for the following 13 hours he makes his viewers believe that Ruskin was right. The series was extraordinarily successful, and the primary lesson that producers at the BBC learned from it was that the "personal view" was key: the series worked not because it provided many beautiful images from the history of Western art—though it did that, and filmed on 35mm stock as well, which is why modern DVDs of the show look so good—but because viewers loved being guided by Clark. -

Crister Skoglund Prolog Till Abacusen Och Rosen 1

http://www.diva-portal.org Postprint This is the accepted version of a paper published in . This paper has been peer-reviewed but does not include the final publisher proof-corrections or journal pagination. Citation for the original published paper (version of record): Skoglund, C. (1995) Prolog till Abacusen och Rosen Dialoger, (34/35): 36-51 Access to the published version may require subscription. N.B. When citing this work, cite the original published paper. Permanent link to this version: http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:sh:diva-32107 Crister Skoglund Prolog till Abacusen och Rosen 1 Prolog till ”Abacusen och Rosen” Crister Skoglund En text skriven inför en uppläsning på Dramaten av Jacob Bronowskis pjäs ”Abacusen och Rosen” i tidskriftens Dialogers regi. Att konst och vetenskap är två fundamentalt olika verksamheter, som attraherar två diametralt motsatta typer av personligheter, framkastas inte sällan som en självklar ”sanning” på kultursidor och i kvällssamtal. Mot det kyligt beräknande vetenskapliga temperamentet ställs då den varmt och lidelsefullt engagerade konstnärssjälen. Den typiske ”Konstnären” och ”Vetenskapsmannen” - och särskilt då naturvetenskapsmannen i sin vita rock - ställs inte sällan upp som varandras motsatser både när det gäller sättet att tänka och förhålla sig till världen. Men är denna uppdelning verkligen ”sann”? Är skillnaderna faktiskt så stora mellan konstnärlig och vetenskaplig verksamhet som vi ibland vill göra gällande? Eller är det kanske så att skillnaderna enbart är skillnader på ytan, och att likheterna i det grundläggande förhållningssättet i själva verkat är större än olikheterna? Att vetenskapligt och konstnärligt skapande i grund och botten förutsätter personer med ett rätt likartat temperament? En som intensivt sysselsatte sig med denna problematik och på olika sätt försökte blottlägga likheter och skillnader mellan konstens och vetenskapens arbetssätt och villkor var den engelske matematikern och litteraturvetaren Jacob Bronowski.