JG Crowther and the Making of Interwar British Culture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric Kandel Form in Which This Information Is Stored

RESEARCH I NEWS pendent, this system would be expected to [2] HEEsch and J E Bums. Distance estimation work quite well, since the new recruit bees by foraging honeybees, The Journal ofExperi mental Biology, Vo1.199, pp. 155-162, 1996. tend to take the same route as the experi [3] M V Srinivasan, S W Zhang, M Lehrer, and T enced scout bee. What dOJhe ants do when S Collett, Honeybee Navigation en route to they cover similarly several kilometres on the goal: Visual flight control and odometry, foot to look for food? Preliminary evidence The Journal ofExperimental Biology, Vol. 199, pp. 237-244, 1996. indicates that they don't use an odometer but [4] M V Srinivasan, S W Zhang, M Altwein, and instead might count steps! J Tautz, Honeybee Navigation: Nature and Calibration of the Odometer, Science, Vol. Suggested Reading 287, pp. 851-853, 1996. [1] Karl von Frisch, The dance language and OT Moushumi Sen Sarma, Centre for Ecological Sci ientation of bees, Harvard Univ. Press, Cam ences, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore 560012, bridge, MA, USA, 1993. India. Email: [email protected] Learning from a Sea Snail: modify future behaviour, then memory is the Eric Kandel form in which this information is stored. Together, they represent one of the most valuable and powerful adaptations ever to Rohini Balakrishnan have evolved in nervous systems, for they In the year 2000, Eric Kandel shared the allow the future to access the past, conferring Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicinel flexibility to behaviour and improving the with two other neurobiologists: Arvid chances of survival in unpredictable, rapidly Carlsson and Paul Greengard. -

Introduction and Historical Perspective

Chapter 1 Introduction and Historical Perspective “ Nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution. ” modified by the developmental history of the organism, Theodosius Dobzhansky its physiology – from cellular to systems levels – and by the social and physical environment. Finally, behaviors are shaped through evolutionary forces of natural selection OVERVIEW that optimize survival and reproduction ( Figure 1.1 ). Truly, the study of behavior provides us with a window through Behavioral genetics aims to understand the genetic which we can view much of biology. mechanisms that enable the nervous system to direct Understanding behaviors requires a multidisciplinary appropriate interactions between organisms and their perspective, with regulation of gene expression at its core. social and physical environments. Early scientific The emerging field of behavioral genetics is still taking explorations of animal behavior defined the fields shape and its boundaries are still being defined. Behavioral of experimental psychology and classical ethology. genetics has evolved through the merger of experimental Behavioral genetics has emerged as an interdisciplin- psychology and classical ethology with evolutionary biol- ary science at the interface of experimental psychology, ogy and genetics, and also incorporates aspects of neuro- classical ethology, genetics, and neuroscience. This science ( Figure 1.2 ). To gain a perspective on the current chapter provides a brief overview of the emergence of definition of this field, it is helpful -

Full List of Files Released L C P First Date Last Date Scope/Content

Full list of files released L C P First Date Last Date Scope/Content Former Ref Note KV 2 WORLD WAR II KV 2 German Intelligence Agents and Suspected Agents KV 2 3386 06/03/1935 18/08/1953 Greta Lydia OSWALD: Swiss. Imprisoned in PF 45034 France on grounds of spying for Germany in 1935, OSWALD was said to be working for the Gestapo in 1941 KV 2 3387 12/11/1929 12/01/1939 Oscar Vladimirovich GILINSKY alias PF 46098 JILINSKY, GILINTSIS: Latvian. An arms dealer VOL 1 in Paris, in 1937 GILINSKY was purchasing arms for the Spanish Popular Front on behalf of the Soviet Government. In November 1940 he was arrested by the Germans in Paris but managed to obtain an exit permit. He claimed he achieved this by bribing individual Germans but, after ISOS material showed he was regarded as an Abwehr agent, he was removed in Trinidad from a ship bound for Buenos Aires and brought to Camp 020 for interrogation. He was deported in 1946 KV 2 3388 13/01/1939 16/02/1942 Oscar Vladimirovich GILINSKY alias PF 46098 JILINSKY, GILINTSIS: Latvian. An arms dealer VOL 2 in Paris, in 1937 GILINSKY was purchasing arms for the Spanish Popular Front on behalf of the Soviet Government. In November 1940 he was arrested by the Germans in Paris but managed to obtain an exit permit. He claimed he achieved this by bribing individual Germans but, after ISOS material showed he was regarded as an Abwehr agent, he was removed in Trinidad from a ship bound for Buenos Aires and brought to Camp 020 for interrogation. -

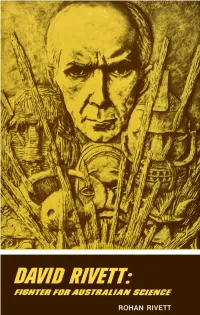

David Rivett

DAVID RIVETT: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE OTHER WORKS OF ROHAN RIVETT Behind Bamboo. 1946 Three Cricket Booklets. 1948-52 The Community and the Migrant. 1957 Australian Citizen: Herbert Brookes 1867-1963. 1966 Australia (The Oxford Modern World Series). 1968 Writing About Australia. 1970 This page intentionally left blank David Rivett as painted by Max Meldrum. This portrait hangs at the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation's headquarters in Canberra. ROHAN RIVETT David Rivett: FIGHTER FOR AUSTRALIAN SCIENCE RIVETT First published 1972 All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission © Rohan Rivett, 1972 Printed in Australia at The Dominion Press, North Blackburn, Victoria Registered in Australia for transmission by post as a book Contents Foreword Vll Acknowledgments Xl The Attack 1 Carving the Path 15 Australian at Edwardian Oxford 28 1912 to 1925 54 Launching C.S.I.R. for Australia 81 Interludes Without Playtime 120 The Thirties 126 Through the War-And Afterwards 172 Index 219 v This page intentionally left blank Foreword By Baron Casey of Berwick and of the City of Westminster K.G., P.C., G.C.M.G., C.H., D.S.a., M.C., M.A., F.A.A. The framework and content of David Rivett's life, unusual though it was, can be briefly stated as it was dominated by some simple and most unusual principles. He and I met frequently in the early 1930's and discussed what we were both aiming to do in our respective fields. He was a man of the most rigid integrity and way of life. -

Consciousness Eclipsed: Jacques Loeb, Ivan P. Pavlov, and the Rise of Reductionistic Biology After 1900

Consciousness and Cognition Consciousness and Cognition 14 (2005) 219–230 www.elsevier.com/locate/concog Consciousness eclipsed: Jacques Loeb, Ivan P. Pavlov, and the rise of reductionistic biology after 1900 Ralph J. Greenspan*, Bernard J. Baars The Neurosciences Institute, 10640 John Jay Hopkins Dr., San Diego, CA 92121, United States Received 17 May 2004 Available online 25 November 2004 Abstract The life sciences in the 20th century were guided to a large extent by a reductionist program seeking to explain biological phenomena in terms of physics and chemistry. Two scientists who figured prominently in the establishment and dissemination of this program were Jacques Loeb in biology and Ivan P. Pavlov in psychological behaviorism. While neither succeeded in accounting for higher mental functions in physical- chemical terms, both adopted positions that reduced the problem of consciousness to the level of reflexes and associations. The intellectual origins of this view and the impediment to the study of consciousness as an object of inquiry in its own right that it may have imposed on peers, students, and those who followed is explored. Ó 2004 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. Keywords: History of ideas; Reductionism; Tropism; Conditional reflex 1. Introduction The current acceptance of consciousness as a suitable object of study in the life sciences came late in the 20th century (Flanagan, 1984). By that time other biological processes—physiology, biochemistry, genetics, embryology, and even many aspects of brain function—had long since * Corresponding author. Fax: +1 858 626 2099. E-mail addresses: [email protected] (R.J. Greenspan), [email protected] (B.J. -

Notes to Robert Curtis's Presentation at WL2018

Notes to Robert Curtis's presentation at WL2018 R. T. Curtis Some students of H.F. Baker Henry Frederick Baker was a hugely influential Cambridge geometer in the late 19th and early 20th century. His students included Coxeter who went on to become one of the most important geometers in the 20C; du Val and Edge, who were distinguished algebraic ge- ometers; and Todd of the Todd-Coxeter coset enumeration algorithm. The eminent number theorist Mordell was another student, as was Jacob Bronowski who wrote and presented The Ascent of Man which in the 1960s was a popular television series about the rise of civilization. Bronowski's daughter Lisa (later Lisa Jardine) also studied Mathematics at Cambridge in the year above me but changed to English in her third year and went on to become Professor of Renaissance Studies at Queen Mary, University of London. This talk will begin with the contribution of Todd. The synthematic totals preserved by the symmetric group S6 The 15 partitions of six letters into pairs are known as synthemes; a set of five synthemes such that every pair appears is a synthematic total; there are just 6 of these totals, and so the symmetric group S6 permutes both the original 6 letters and the 6 totals. Todd wrote the totals on the board in his 1967 Cambridge Part III course which I attended, and demonstrated important properties of these two non-permutation identical actions. From S6 to M12 to M24 Todd's lectures demonstrated an important method of constructing groups: Use a well- known group to construct a new combinatorial or geometric structure; observe that the new structure possesses more symmetries than just the group you used in its construction. -

Uma Breve História Da Geometria Molecular Sob a Perspectiva Didático-Epistemológica De Guy Brousseau

Uma Breve História da Geometria Molecular sob a Perspectiva Didático-Epistemológica de Guy Brousseau Kleyfton Soares da Silva Laerte Silva da Fonseca Johnnatan Duarte de Freitas RESUMO O objetivo desta pesquisa foi analisar a evolução histórica da Geometria Molecular (GM), de modo a apresentar discussões, limitações, dificuldades e avanços associados à concepção do saber em jogo e, através disso, contribuir com elementos para análise crítica da organização didática em livros e sequências de ensino. Foi realizado um levantamento histórico na perspectiva epistemológica defendida por Brousseau (1983), em que a compreensão da evolução conceitual do conteúdo visado pelo estudo é alcançada quando há o entrelaçamento de fatos que ajudam a identificar obstáculos que limitaram e/ou limitam a aprendizagem de um dado conteúdo. Trata-se de uma abordagem inédita tanto pelo direcionamento do conteúdo como pela metodologia adotada. A análise histórica permitiu traçar um conjunto de oito obstáculos que por um lado estagnou a evolução do conceito de GM e por outro impulsionou cientistas a buscarem alternativas teóricas e metodológicas para resolver os problemas que foram surgindo ao longo do tempo. O estudo mostrou que a questão da visualização em química e da necessidade de manipulação física de modelos moleculares é constitutiva da própria evolução história da GM. Esse ponto amplifica a necessidade de superação contínua dos obstáculos epistemológicos e cognitivos associados às representações moleculares. Palavras-chave: Análise Epistemológica. Geometria -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

Fritz Arndt and His Chemistry Books in the Turkish Language

42 Bull. Hist. Chem., VOLUME 28, Number 1 (2003) FRITZ ARNDT AND HIS CHEMISTRY BOOKS IN THE TURKISH LANGUAGE Lâle Aka Burk, Smith College Fritz Georg Arndt (1885-1969) possibly is best recog- his “other great love, and Brahms unquestionably his nized for his contributions to synthetic methodology. favorite composer (5).” The Arndt-Eistert synthesis, a well-known reaction in After graduating from the Matthias-Claudius Gym- organic chemistry included in many textbooks has been nasium in Wansbek in greater Hamburg, Arndt began used over the years by numerous chemists to prepare his university education in 1903 at the University of carboxylic acids from their lower homologues (1). Per- Geneva, where he studied chemistry and French. Fol- haps less well recognized is Arndt’s pioneering work in lowing the practice at the time of attending several in- the development of resonance theory (2). Arndt also stitutions, he went from Geneva to Freiburg, where he contributed greatly to chemistry in Turkey, where he studied with Ludwig Gattermann and completed his played a leadership role in the modernization of the sci- doctoral examinations. He spent a semester in Berlin ence (3). A detailed commemorative article by W. Walter attending lectures by Emil Fischer and Walther Nernst, and B. Eistert on Arndt’s life and works was published then returned to Freiburg and worked with Johann in German in 1975 (4). Other sources in English on Howitz and received his doctorate, summa cum laude, Fritz Arndt and his contributions to chemistry, specifi- in 1908. Arndt remained for a time in Freiburg as a cally discussions of his work in Turkey, are limited. -

AUTOBIOGRAPHY and HISTORY on SCREEN: the Life and Times of Lord

AUTOBIOGRAPHY AND HISTORY ON SCREEN: The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten 1 Abstract: The television series, The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten (1968), was a unique collaboration between an independent production company, Associated- Rediffusion, a national museum, the Imperial War Museum, and one of the most famous aristocratic and military figures of the 20th century, Lord Mountbatten. Furthermore, Mountbatten was the programme’s presenter, appearing on screen to describe his experiences autobiographically. Through the use of film and images, Mountbatten’s ‘life’ was intertwined with the historical ‘times’ of over half a century. Though praised at the point of its release to British audiences in 1969 by the public, critics and historians alike, The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten has since largely been ignored by scholars interested in the history-on-television genre. By detailing the origins, format, production and reception of the series, and by comparing it to both The Great War (1964) and The World at War (1973-1974), which were also produced in conjunction with the Imperial War Museum, the immediate success and subsequent failure of The Life and Times of Lord Mountbatten to attract popular and academic attention provides an argument for widening the discussion on television history and its limited categorizations. Key words: autobiography, history, television, Imperial War Museum, The Great War, The World at War. 2 To tell the story of this century on television is in itself a formidable task. To focus this story on one single man, however remarkable his career, breaks new ground. This series is not only about Lord Mountbatten, it is with him and that gives this television history a unique dimension.1 Academic literature concerning factual history programmes is abundant with references to The Great War and The World at War, which were television series made in collaboration with the Imperial War Museum (IWM) from 1963-1964 and 1971-1974 respectively. -

Historical Group

Historical Group NEWSLETTER and SUMMARY OF PAPERS No. 69 Winter 2016 Registered Charity No. 207890 COMMITTEE Chairman: Dr John A Hudson ! Dr Noel G Coley (Open University) Graythwaite, Loweswater, Cockermouth, ! Dr Christopher J Cooksey (Watford, Cumbria, CA13 0SU ! Hertfordshire) [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Prof Alan T Dronsfield (Swanwick, Secretary: Prof. John W Nicholson ! Derbyshire) 52 Buckingham Road, Hampton, Middlesex, ! Prof Ernst Homburg (University of TW12 3JG [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Maastricht) Membership Prof Bill P Griffith ! Prof Frank James (Royal Institution) Secretary: Department of Chemistry, Imperial College, ! Dr Michael Jewess (Harwell, Oxon) London, SW7 2AZ [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Dr David Leaback (Biolink Technology) Treasurer: Dr Peter J T Morris ! Mr Peter N Reed (Steensbridge, 5 Helford Way, Upminster, Essex RM14 1RJ ! Herefordshire) [e-mail: [email protected]] ! Dr Viviane Quirke (Oxford Brookes Newsletter Dr Anna Simmons ! University) Editor Epsom Lodge, La Grande Route de St Jean, !Prof Henry Rzepa (Imperial College) St John, Jersey, JE3 4FL ! Dr Andrea Sella (University College) [e-mail: [email protected]] Newsletter Dr Gerry P Moss Production: School of Biological and Chemical Sciences, Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London E1 4NS [e-mail: [email protected]] http://www.chem.qmul.ac.uk/rschg/ http://www.rsc.org/membership/networking/interestgroups/historical/index.asp 1 RSC Historical Group NewsletterNo. 69 Winter 2016 Contents From the Editor 2 Message from the Chair 3 ROYAL SOCIETY OF CHEMISTRY HISTORICAL GROUP MEETINGS 3 “The atom and the molecule”: celebrating Gilbert N. Lewis 3 RSCHG NEWS 4 MEMBERS’ PUBLICATIONS 4 PUBLICATIONS OF INTEREST 5 CAN YOU HELP? - Update from the summer 2015 newsletter 6 Feedback from the summer 2015 newsletter 6 NEWS AND UPDATES 7 SOCIETY NEWS 8 SHORT ESSAYS 8 175 Years of Institutionalised Chemistry and Pharmacy – William H. -

BRADWELL LODGE (Formerly the Rectory) BRADWELL on SEA

MALDON DISTRICT COUNCIL BRADWELL LODGE (formerly the Rectory) BRADWELL ON SEA TM 004 067 Originally a C16 house on a moated site, considerably extended by John Johnson, architect, with the gardens laid out by the agricultural improver and rector (Rev. Sir Henry Bate Dudley) in the late C18. HISTORIC DEVELOPMENT The north wing of Bradwell Lodge was originally a moated Tudor house dating from 1520. It was believed to have been given to Ann of Cleeves by Henry VIII as part of the divorce settlement. The Rev. Sir Henry Bate Dudley (1745-1824) purchased the advowson of Bradwell-juxta-Mare in 1781 for a reported sum of £1,500. He acted as curate for the absentee rector George Pawson until 1797 and leased the neglected glebe from him. Writing to the bishop in March 1798, Bate Dudley explained how when he had arrived at Bradwell the glebe of 300 acres was in so ruinous a state from flooding and neglect that no one would farm it. Bate Dudley drained the glebe and the first mark of recognition of what he had done came from the Society of Arts in 1788 when he was granted the Silver Medal for reclaiming the land from the sea. In his report to the Society, Bate Dudley said that he had enclosed 45 acres by September 1786 and by 1800, when he was awarded the Gold Medal, he had reclaimed 206 acres and was growing corn on the land. He spent £28,000 of his personal fortune in draining the marshland round Bradwell and eventually reclaimed over 250 acres of marshland and applied mole drainage to heavy land.