Classroom ABSTRACT Arts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Work Diet, Exercise, Reduced Stress Levels, Adequate Rest

The Magazine of the Greater Valparaiso Chamber of Commerce Volume 4 Issue 3 Summer 2004 Staying Healthy is “Heart”Work Diet, exercise, reduced stress levels, adequate rest . You know the way to a healthy heart. You also know that when special care of your heart and circulatory system is needed, the cardiology physicians and healthcare professionals at NICP, P.C. are the folks to call. We provide quality, affordable, state-of-the-art technology and personal care that have made us the most trusted and respected cardiologists in the area. Offering: • Clinical Evaluations • Consultations • Nuclear Stress Tests • Echocardiogram • 24 Hour Holter Monitor • Arterial and Venous Dopplers • Permanent Pacemaker and Transtelephonic Evaluations Keith Atassi, M.D. • G. David Beiser, M.D. Northwest Indiana Cardiovascular Physicians, P.C. John A. Forchetti, M.D. • Fred J. Harris, M.D. Akram Kholoki, M.D. • Daniel P. Linert, M.D. 2000 Roosevelt Rd. in Valparaiso Hector J. Marchand, M.D. • M. Satya Rao, M.D. 800-727-6337 Michael L. Wheat, M.D. 219-531-9419 contents Cover: Foreground— Bob & Sandy Coolman 5 Inside left to right— Keith & Becky Kirkpatrick, Sweet Home Valparaiso Bill & Rose Ferngren and Jack the Dog. How and Why We Live Where We Live. Feature Stories Special Features Home Mountain to put graphic here. 5 10 14 12-13 Insert Valparaiso is a city of From Broadway shows and edgy, From quiet candlelight to family 2004 Community Half Century Awards neighborhoods, each with its contemporary theater to fun and boisterous sports bars, Improvement Award winners. own identity, its own sense of musicians and bands that Valparaiso offers dining community and its own sense appeal to a wide variety of tastes, experiences to suit every style, of self. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

From Zones of Conflict Comes Music for Peace

From zones of conflict comes music for peace. What is Fambul Tok? Around a crackling bonfire in a remote village, the war finally ended. Seven years since the last bullet was fired, a decade of fighting in The artists on this album have added their voices to a high-energy, Sierra Leone found resolution as people stood and spoke. Some had urgent call for forgiveness and deep dialogue. They exemplify the perpetrated terrible crimes against former friends. Some had faced creative spirit that survives conflict, even war. From edgy DJs and horrible losses: loved ones murdered, limbs severed. But as they soulful singer-songwriters, from hard-hitting reggae outfits to told their stories, admitted their wrongs, forgave, danced, and sang transnational pop explorers, they have seen conflict and now sow together, true reconciliation began. This is the story of “Fambul Tok” peace. They believe in the power of ordinary people - entire com- (Krio for “family talk”), and it is a story the world needs to hear. munities ravaged by war - to work together to forge a lasting peace. They believe in Fambul Tok. Fambul Tok originated in the realization that peace can’t be imposed from the outside, or the top down. Nor does it need to be. The com- munity led and owned peacebuilding in Sierra Leone is teaching us that communities have within them the resources they need for their own healing. Join the fambul at WAN FAMBUL O N E FA M I LY FAMBULTOK.COM many voices ... Wi Na Wan Fambul BajaH + DRY EYE Crew The groundbreaking featuring Rosaline Strasser-King (LadY P) and Angie 4:59 grassroots peacebuilding of Nasle Man AbjeeZ 5:33 the people of Sierra Leone Say God Idan RaicHel Project has also been documented featuring VieuX Farka Toure 4:59 in the award-winning film Ba Kae Vusi MAHlasela 5:05 Fambul Tok, and in its Guttersnipe BHI BHiman 6:52 companion book, Fambul Shim El Yasmine 5:10 Tok. -

Songs of Sinatra Steve Tyrell

Songs of Sinatra Steve Tyrell I never met Frank Sinatra, but I wish I had. Frank created a genre of musical expression that has remained timeless and everlasting, and unlike the disposable pop culture of today will live forever as long as it has a chance to be heard. Frank Sinatra and his music have no expiration date; they are always cool and current. He sang the great songs and expressed the words in a way that makes the listener understand the intentions of the songwriter. I only met the Sinatra family after I started to make my standards albums. I received a very complimentary message after my second album "Standard Time" from Frank Sinatra, Jr. He told me how much he liked my first two albums and encouraged me to continue doing what I was doing. He complimented my vocal approach, my arrangements and the musicians I chose to use on those albums, many of whom he knew personally and had worked with his father. Nancy Sinatra had also gone way out of her way to encourage me and compliment my standards albums. We have become great friends and have often played the same venues around the country as I have also done with Frank, Jr. Tina was the next family member to encourage me, and we have become very good friends. She comes to my performances and has always referred to my albums and performances "as me keeping their music alive." Imagine, me keeping Frank's music alive: quite an encouraging statement, but that's what Tina, Frank and Nancy have told me ever since I started making my standards albums. -

Download and Upload and If You Have a Low Data Rate, You Can't Do Any of Those Things, No Matter How Smart Or Motivated You Are

Produced by VRMB. Sponsored by Track Hospitality Software. Ep. 1: The Wake-up Call 2 Ep. 2: Journey into Advocacy 23 Ep. 3: Go Together 39 Ep. 4: The Big Day 57 Ep. 5: Money 75 Ep. 6: We Need to Talk 89 Ep. 7: Telling Your Story 109 Ep. 8: When It All Goes Wrong 122 Ep. 9: Big Ideas 143 Ep. 10: Where Do We Go From Here 161 Ep. 1: The Wake-up Call Eric Bay (ANP) Things got out of hand and city council members ran on platforms that said we want to rein this in and stop this. Unfortunately, what they did was take several draconian measures and backward steps in eliminating about 70% of all of the formerly licensed and legal properties in New Orleans. Megan McCrea (NASTRA) The city was basically trying to pass a ban on short term rentals. And even those of us who were in operation would have to stop. Phil Minardi (Expedia) Right now in the US, we have over 4200 municipalities, I would say, decent guests is that at least half of them at this point, have either had the conversation about regulations or are currently having them right now. Paige Teel (NEVRP) We are trying to figure out exactly how we want to be defined, which has always been something that's been hard for us because we've we're not gonna say flown under the radar, but we've also not been regulated. So there's kind of a two edged sword to that, especially now due to the Coronavirus. -

Songs by Title

16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Songs by Title 16,341 (11-2020) (Title-Artist) Title Artist Title Artist (I Wanna Be) Your Adams, Bryan (Medley) Little Ole Cuddy, Shawn Underwear Wine Drinker Me & (Medley) 70's Estefan, Gloria Welcome Home & 'Moment' (Part 3) Walk Right Back (Medley) Abba 2017 De Toppers, The (Medley) Maggie May Stewart, Rod (Medley) Are You Jackson, Alan & Hot Legs & Da Ya Washed In The Blood Think I'm Sexy & I'll Fly Away (Medley) Pure Love De Toppers, The (Medley) Beatles Darin, Bobby (Medley) Queen (Part De Toppers, The (Live Remix) 2) (Medley) Bohemian Queen (Medley) Rhythm Is Estefan, Gloria & Rhapsody & Killer Gonna Get You & 1- Miami Sound Queen & The March 2-3 Machine Of The Black Queen (Medley) Rick Astley De Toppers, The (Live) (Medley) Secrets Mud (Medley) Burning Survivor That You Keep & Cat Heart & Eye Of The Crept In & Tiger Feet Tiger (Down 3 (Medley) Stand By Wynette, Tammy Semitones) Your Man & D-I-V-O- (Medley) Charley English, Michael R-C-E Pride (Medley) Stars Stars On 45 (Medley) Elton John De Toppers, The Sisters (Andrews (Medley) Full Monty (Duets) Williams, Sisters) Robbie & Tom Jones (Medley) Tainted Pussycat Dolls (Medley) Generation Dalida Love + Where Did 78 (French) Our Love Go (Medley) George De Toppers, The (Medley) Teddy Bear Richard, Cliff Michael, Wham (Live) & Too Much (Medley) Give Me Benson, George (Medley) Trini Lopez De Toppers, The The Night & Never (Live) Give Up On A Good (Medley) We Love De Toppers, The Thing The 90 S (Medley) Gold & Only Spandau Ballet (Medley) Y.M.C.A. -

Download 1 File

Starship Troopers by Robert Heinlein Table of Contents Starship Troopers Chapter 8 Chapter 1 Chapter 9 Chapter 2 Chapter 10 Chapter 3 Chapter 11 Chapter 4 Chapter 12 Chapter 5 Chapter 13 Chapter 6 Chapter 14 Chapter 7 Chapter 1 Come on, you apes! You wanta live forever? — Unknown platoon sergeant, 1918 I always get the shakes before a drop. I’ve had the injections, of course, and hypnotic preparation, and it stands to reason that I can’t really be afraid. The ship’s psychiatrist has checked my brain waves and asked me silly questions while I was asleep and he tells me that it isn’t fear, it isn’t anything important — it’s just like the trembling of an eager race horse in the starting gate. I couldn’t say about that; I’ve never been a race horse. But the fact is: I’m scared silly, every time. At D-minus-thirty, after we had mustered in the drop room of theRodger Young , our platoon leader inspected us. He wasn’t our regular platoon leader, because Lieutenant Rasczak had bought it on our last drop; he was really the platoon sergeant, Career Ship’s Sergeant Jelal. Jelly was a Finno-Turk from Iskander around Proxima — a swarthy little man who looked like a clerk, but I’ve seen him tackle two berserk privates so big he had to reach up to grab them, crack their heads together like coconuts, step back out of the way while they fell. Off duty he wasn’t bad — for a sergeant. -

By Song Title

Solar Entertainments Karaoke Song Listing By Song Title 3 Britney Spears 2000s 17 MK 2010s 22 Lily Allen 2000s 39 Queen 1970s 679 Fetty Wap 2010s 711 Beyonce 2010s 1973 James Blunt 2000s 1999 Prince 1980s 2002 Anne Marie 2010s #ThatPower Will.I.Am & Justin Bieber 2010s 007 (Shanty Town) Desmond Dekker & The Aces 1960s 1 800 273 8255 Logic & Alessia Cara & Khalid 2010s 1 Thing Amerie 2000s 10/10 Paolo Nutini 2010s 10000 Hours Dan & Shay & Justin Bieber 2010s 18 & Life Skid Row 1980s 2 Become 1 Spice Girls 1990s 2 Hearts Kylie Minogue 2000s 20th Century Boy T Rex 1970s 21 Guns Green Day 2000s 21st Century Breakdown Green Day 2000s 21st Century Christmas Cliff Richard 2000s 22 (Twenty Two) Taylor Swift 2010s 24K Magic Bruno Mars 2010s 2U David Guetta & Justin Bieber 2010s 3 AM Busted 2000s 3 Nights Dominic Fike 2010s 3 Words Cheryl Cole 2000s 30 Days Saturdays 2010s 34+35 Ariana Grande 2020s 4 44 Jay Z 2010s 4 In The Morning Gwen Stefani 2000s 4 Minutes Madonna & Justin Timberlake 2000s 5 Colours In Her Hair McFly 2000s 5,6,7,8 Steps 1990s 500 Miles (I'm Gonna Be) Proclaimers 1980s 7 Rings Ariana Grande 2010s 7 Things Miley Cyrus 2000s 7 Years Lukas Graham 2010s 74 75 Connells 1990s 9 To 5 Dolly Parton 1980s 90 Days Pink & Wrabel 2010s 99 Red Balloons Nena 1980s A Bad Dream Keane 2000s A Blossom Fell Nat King Cole 1950s A Change Would Do You Good Sheryl Crow 1990s A Cover Is Not The Book Mary Poppins Returns Soundtrack 2010s A Design For Life Manic Street Preachers 1990s A Different Beat Boyzone 1990s A Different Corner George Michael 1980s -

Real-Life Literacy Instruction, K-3: a Handbook for Teachers

The Cultural Practices of Literacy Study University of British Columbia The creation of this Handbook was supported by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada Real-life Literacy Instruction, K-3: A Handbook for Teachers Victoria Purcell-Gates With Model Lessons by: Andrea Beatty Jason Hodgins Allison Jambor Sarah Loat Tazmin Manji Ashley McKittrick Marianne McTavish Colleen Stebner Aimée Dione Williams Tracy Gates, Editorial Assistant The Cultural Practices of Literacy Study University of British Columbia The creation of this Handbook was supported by the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter 1. Creating Real-Life Literacy Activities for Young Readers and Writers by Victoria Purcell-Gates 1 Chapter 2. Learning the Literacy Worlds of Your Students 7 Intro by Victoria Purcell-Gates 7 Model Lesson #1: The “To-Do” List by Allison Jambor 7 Learning what is 'Real-Life' for Your Students by Victoria Purcell-Gates 19 Model Lesson #2: Cooking Up Some Authenticity by Sarah Loat 29 Chapter 3 Creating Contexts for Real-Life Literacy 41 Authentic Contexts: Requirement for Real-Life Literacy by Victoria Purcell-Gates 41 Model Lesson #3: The Sears Catalogue Comes to School by Marianne McTavish 42 Creating the Contexts for Real-Life Literacy by Victoria Purcell-Gates 56 Model Lesson #4: Guinea Pigs in the Classroom by Colleen Stebner 65 Chapter 4 Writing and Reading Real Life Texts for Real Life Purposes 79 Looking Back at the Research by Victoria Purcell-Gates 79 Model Lesson #5: Loving Letter -

Check Your Progress

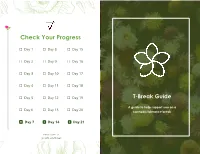

Check Your Progress ☐ Day 1 ☐ Day 8 ☐ Day 15 ☐ Day 2 ☐ Day 9 ☐ Day 16 ☐ Day 3 ☐ Day 10 ☐ Day 17 cc ☐ Day 4 ☐ Day 11 ☐ Day 18 ☐ Day 5 ☐ Day 12 ☐ Day 19 T-Break Guide A guide to help support you on a ☐ Day 6 ☐ Day 13 ☐ Day 20 cannabis tolerance break ☐ Day 7 ☐ Day 14 ☐ Day 21 T-Break Guide™ v3 go.uvm.edu/tbreak Hello. An Introduction . If you use cannabis, at some point, you should take a tolerance break. Like anything else, your body builds up a tolerance: you need more to . get high. A T-Break could help you save money and also keep balance. The hard news is that if you partake most days, a true T-Break should be at least 21 days long, since it takes around three weeks or more for THC . to leave your system. (That’s because THC bonds to fat, which is stored in the body longer.) . I created this guide because people would tell me that when they set out . to take a T-Break, they only lasted a few days. Sometimes they felt ashamed because it was harder than they thought. There is no need to . feel bad… . …but it can be hard to take a break. People usually find some aspect of . getting high beneficial. Cannabis causes fewer harms than some other drugs and creates less cravings. For those very reasons, ironically, some . people find it challenging to find a balance with cannabis: they might think that cannabis has no harms and no cravings. -

A Description of Figurative Meaning Found in Michelle Branch’S the Spirit Room Album

A DESCRIPTION OF FIGURATIVE MEANING FOUND IN MICHELLE BRANCH’S THE SPIRIT ROOM ALBUM A PAPER WRITTEN BY NOVA SITUMEANG REG.NO. 172202009 ENGLISH DIPLOMA 3 STUDY PROGRAM FACULTY OF CULTURAL STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF SUMATERA UTARA MEDAN 2020 Universitas Sumatera Utara . Universitas Sumatera Utara Universitas Sumatera Utara AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I the undersigned NOVA SITUMEANG, hereby declare that I am the sole author of this paper. To the best of my knowledge this paper contains no material previously published by any other person except where due acknowledgement has been made. This paper contains no material which has been accepted as part of the requirements of any other academic degree or non-degree program, in English or in any other language. Signed : Date : August, 2020 i Universitas Sumatera Utara COPYRIGHT DECLARATION Name : NOVA SITUMEANG Title of Paper : A DESCRIPTION OF FIGURATIVE MEANING FOUND IN MICHELLE BRANCH’S THE SPIRIT ROOM ALBUM Qualification : D-III / Ahli Madya Study Program : English language I hope that this paper should be available for reproduction at the direction the Librarian of English Diploma 3 Study Program, Faculty of Cultural Studies, University of Sumatera Utara on the understanding that users made aware to their obligation under law of the Republic of Indonesia. Signed : Date : August, 2020 ii Universitas Sumatera Utara ABSTRAK Judul dari kertas karya ini adalah “A Description of Figurative Meaning Found in Michelle Branch’s The Spirit Room Album”. Kertas Karya ini bertujuan untuk mendeskripsikan majas yang ditemukan di dalam lagu-lagu milik Michelle Branch pada Album The Spirit Room. Teknik yang digunakan untuk mendeskripsikan data ini yaitu dengan membaca lirik lagu Michelle Branch yang diambil dari Albumnya yang berjudul The Spirit Room.