Great Entertainers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARSC Journal, Spring 1992 69 Sound Recording Reviews

SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First Hundred Years CS090/12 (12 CDs: monaural, stereo; ADD)1 Available only from the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, 220 S. Michigan Ave, Chicago, IL, for $175 plus $5 shipping and handling. The Centennial Collection-Chicago Symphony Orchestra RCA-Victor Gold Seal, GD 600206 (3 CDs; monaural, stereo, ADD and DDD). (total time 3:36:3l2). A "musical trivia" question: "Which American symphony orchestra was the first to record under its own name and conductor?" You will find the answer at the beginning of the 12-CD collection, The Chicago Symphony Orchestra: The First 100 Years, issued by the Chicago Symphony Orchestra (CSO). The date was May 1, 1916, and the conductor was Frederick Stock. 3 This is part of the orchestra's celebration of the hundredth anniversary of its founding by Theodore Thomas in 1891. Thomas is represented here, not as a conductor (he died in 1904) but as the arranger of Wagner's Triiume. But all of the other conductors and music directors are represented, as well as many guests. With one exception, the 3-CD set, The Centennial Collection: Chicago Symphony Orchestra, from RCA-Victor is drawn from the recordings that the Chicago Symphony made for that company. All were released previously, in various formats-mono and stereo, 78 rpm, 45 rpm, LPs, tapes, and CDs-as the technologies evolved. Although the present digital processing varies according to source, the sound is generally clear; the Reiner material is comparable to RCA-Victor's on-going reissues on CD of the legendary recordings produced by Richard Mohr. -

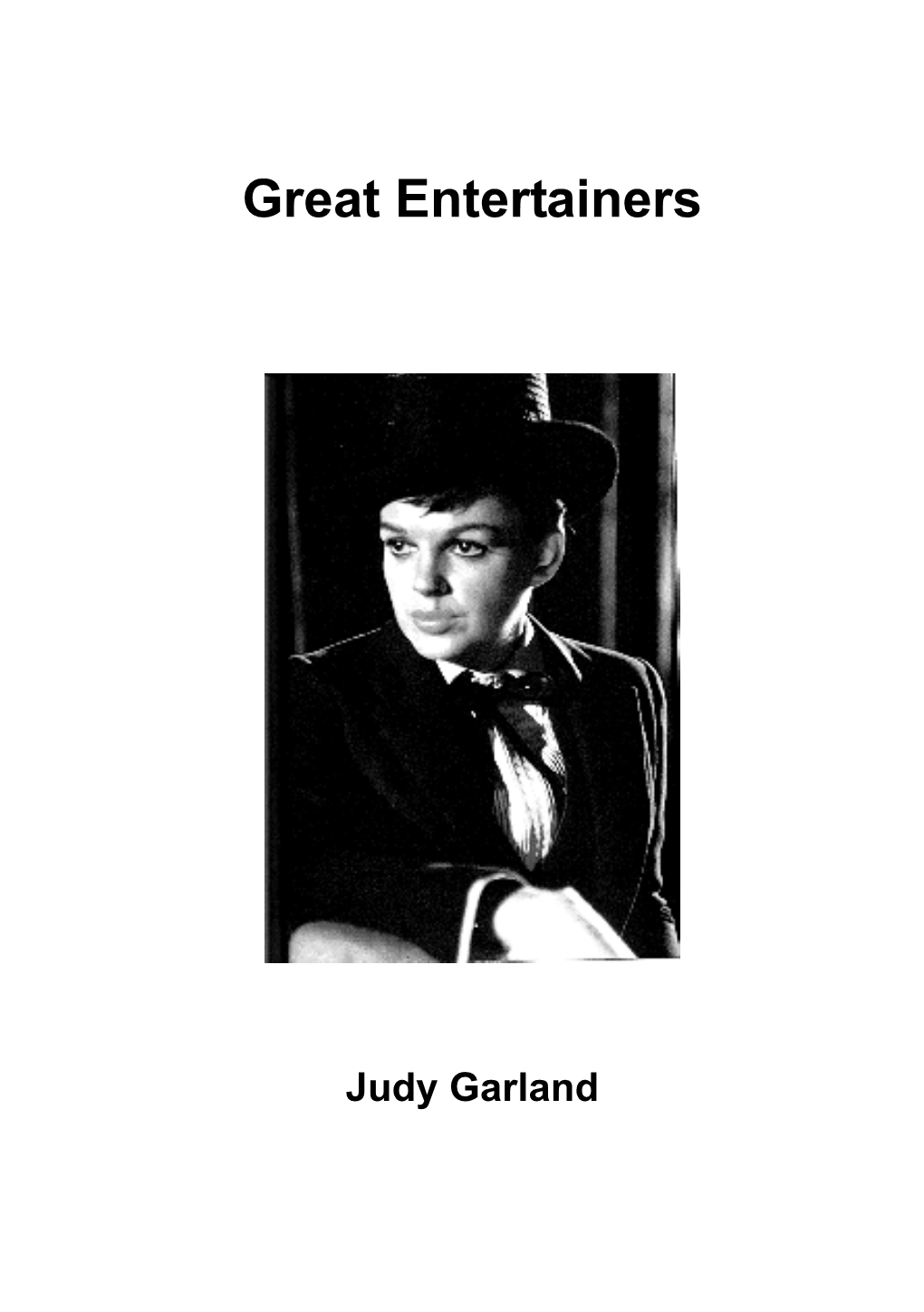

Judy Garland (1922-1969)

1/22 Data Judy Garland (1922-1969) Pays : États-Unis Sexe : Féminin Naissance : Grand-Rapid (S. D.), 10-06-1922 Mort : Londres, 22-01-1969 Note : Chanteuse et actrice américaine Autre forme du nom : Frances Gumm (1922-1969) ISNI : ISNI 0000 0000 8380 6106 (Informations sur l'ISNI) Judy Garland (1922-1969) : œuvres (255 ressources dans data.bnf.fr) Œuvres audiovisuelles (y compris radio) (45) "Un enfant attend. - [2]" "Un enfant attend. - [2]" (2016) (2016) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) de Ernest Gold et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le magicien d'Oz" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2013) (2013) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "La jolie fermière" "Till the clouds roll by" (2013) (2012) de George Wells et autre(s) de Richard Whorf et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "Meet me in St. Louis. - Vincente Minnelli, réal.. - [2]" (2012) (2012) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Le chant du Missouri" "La pluie qui chante. - Richard Whorf, réal.. - [2]" (2011) (2010) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de George Wells et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur data.bnf.fr 2/22 Data "Le chant du Missouri" "Le magicien d'Oz" (2009) (2009) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Victor Fleming et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "The pirate" "La danseuse des Folies Ziegfeld" (2008) (2007) de Vincente Minnelli et autre(s) de Sonya Levien et autre(s) avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur avec Judy Garland (1922-1969) comme Acteur "Parade de printemps" "Un enfant attend. -

![1944-06-30, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5585/1944-06-30-p-395585.webp)

1944-06-30, [P ]

Friday, .Tune 3*), JQ44 THE TOLEDO UNION JOURNAL Page 5 ‘Dear Marfin Heard on a Hollywood Movie Set HOLLY WOOD — John News and Gossip of Stage and Serei n Conte and Marilyn Maxwell are enacting one of the j. - ■- <fr.:-;-UUZ;.,> . .ll . , ..■■j , f -r .. Lr „ — . .. romantic interludes in the Abbott and Costello starrer, Star I*refers Pie “Lost in a Harem," on &tage Stars Use Own Names 26 at M-G-M. «► As the scene begins, Ar Birthday ‘Cake’ , S mF k v i Conte takes Marilyn's hand HOLLYWOOD — Judy Gar In New Screen Vogue and says; {, .* diettjo, land defied tradition on her HOLLYWOOD (Special)—If a present trend continues in “I love you.” Hofljwood wri’ers may soon stop worrying about what names to “I’m — I’m speechless,” twenty-second birthday. ' ' I ’ says Marilyn. “As we say in At a family dinner tendered give their screen characters. Actors will simply use their own America, 'this is so sud the young star by her mother, names—as more and more of them are now doing. den'.” By TED TAYLOR Mrs. Ethel Gilmore, the familiar Take the instance of Jose Iturbi. He made his screen debat AmAmL W. birthday cake was conspicuous playing himself in "Thousads Cheer.” “After I have regained my throne, will you marry by its absence. Judy’s favorite In 20th Century Fox s Four Jills and a Jeep,” they prac- HOLLYWOOD (FP)—This fs probably the first ease on record dessert is chocolate pie. After tically dropped the traditional me?” Conte asks her. M-G-M Stars Two New “Yes,” repli“s Maralyn, as of a man nominating himself for a movie plot. -

In 1925, Eight Actors Were Dedicated to a Dream. Expatriated from Their Broadway Haunts by Constant Film Commitments, They Wante

In 1925, eight actors were dedicated to a dream. Expatriated from their Broadway haunts by constant film commitments, they wanted to form a club here in Hollywood; a private place of rendezvous, where they could fraternize at any time. Their first organizational powwow was held at the home of Robert Edeson on April 19th. ”This shall be a theatrical club of love, loy- alty, and laughter!” finalized Edeson. Then, proposing a toast, he declared, “To the Masquers! We Laugh to Win!” Table of Contents Masquers Creed and Oath Our Mission Statement Fast Facts About Our History and Culture Our Presidents Throughout History The Masquers “Who’s Who” 1925: The Year Of Our Birth Contact Details T he Masquers Creed T he Masquers Oath I swear by Thespis; by WELCOME! THRICE WELCOME, ALL- Dionysus and the triumph of life over death; Behind these curtains, tightly drawn, By Aeschylus and the Trilogy of the Drama; Are Brother Masquers, tried and true, By the poetic power of Sophocles; by the romance of Who have labored diligently, to bring to you Euripedes; A Night of Mirth-and Mirth ‘twill be, By all the Gods and Goddesses of the Theatre, that I will But, mark you well, although no text we preach, keep this oath and stipulation: A little lesson, well defined, respectfully, we’d teach. The lesson is this: Throughout this Life, To reckon those who taught me my art equally dear to me as No matter what befall- my parents; to share with them my substance and to comfort The best thing in this troubled world them in adversity. -

Sunshine State

SUNSHINE STATE A FILM BY JOHN SAYLES A Sony Pictures Classics Release 141 Minutes. Rated PG-13 by the MPAA East Coast East Coast West Coast Distributor Falco Ink. Bazan Entertainment Block-Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Shannon Treusch Evelyn Santana Melody Korenbrot Carmelo Pirrone Erin Bruce Jackie Bazan Ziggy Kozlowski Marissa Manne 850 Seventh Avenue 110 Thorn Street 8271 Melrose Avenue 550 Madison Avenue Suite 1005 Suite 200 8 th Floor New York, NY 10019 Jersey City, NJ 07307 Los Angeles, CA 9004 New York, NY 10022 Tel: 212-445-7100 Tel: 201 656 0529 Tel: 323-655-0593 Tel: 212-833-8833 Fax: 212-445-0623 Fax: 201 653 3197 Fax: 323-655-7302 Fax: 212-833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com CAST MARLY TEMPLE................................................................EDIE FALCO DELIA TEMPLE...................................................................JANE ALEXANDER FURMAN TEMPLE.............................................................RALPH WAITE DESIREE PERRY..................................................................ANGELA BASSETT REGGIE PERRY...................................................................JAMES MCDANIEL EUNICE STOKES.................................................................MARY ALICE DR. LLOYD...........................................................................BILL COBBS EARL PICKNEY...................................................................GORDON CLAPP FRANCINE PICKNEY.........................................................MARY -

The Plagued History of Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, 1965-2009 LAWRENCE SCHULMAN

ARSC JOURNAL VOL. 40, NO. 2 $56&-RXUQDO VOLUME 40, NO. 2 • FALL 2009 )UDQN0DQFLQLDQG0RGHVWR+LJK6FKRRO%DQG·V &RQWULEXWLRQWRWKH1DWLRQDO5HFRUGLQJ5HJLVWU\ 67(9(13(&6(. 7KH3ODJXHG+LVWRU\RI-XG\*DUODQGDQG/L]D0LQQHOOL ´/LYHµDWWKH/RQGRQ3DOODGLXP /$:5(1&(6&+8/0$1 'DYLG/HPLHX[DQGWKH*UDWHIXO'HDG$UFKLYHV -$621.8))/(5 7KH0HWURSROLWDQ2SHUD+LVWRULF%URDGFDVW5HFRUGLQJV FALL 2009 FALL *$5<$*$/2 &23<5,*+7 )$,586( %22.5(9,(:6 6281'5(&25',1*5(9,(:6 &855(17%,%/,2*5$3+< $56&-2851$/+,*+/,*+76 Volume 40, No. 2 ARSC Journal Fall, 2009 EDITOR Barry R. Ashpole ORIGINAL ARTICLES 159 Frank Mancini and Modesto High School Band’s Contribution to the 2005 National Recording Registry STEVEN PECSEK 174 The Plagued History of Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, 1965-2009 LAWRENCE SCHULMAN ARCHIVES 189 David Lemieux and the Grateful Dead Archives JASON KUFFLER DISCOGRAPHY 195 The Metropolitan Opera Historic Broadcast Recordings GARY A. GALO 225 COPYRIGHT & FAIR USE 239 BOOK REVIEWS 281 SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS 317 CURRENT BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 ARSC JOURNAL HIGHLIGHTS 1968-2009 ORIGINAL ARTICLE | LAWRENCE SCHULMAN 7KH3ODJXHG+LVWRU\RIJudy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, In overviewing the ill-fated history of Judy Garland’s last Capitol Records album, Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, recorded on 8 and 15 November WKHDXWKRUHQGHDYRUVWRFKURQLFOHWKHORQJDQGZLQGLQJHYHQWVVXUURXQGLQJLWVÀUVW release on LP in 1965, its subsequent truncated reissues over the years, its aborted release RQ&DSLWROLQLQLWVFRPSOHWHIRUPDQGÀQDOO\LWVDERUWHGUHOHDVHRQ&ROOHFWRU·V&KRLFH -

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection

Published Sheet Music from the Rudy Vallee Collection The Rudy Vallee collection contains almost 30.000 pieces of sheet music (about two thirds published and the rest manuscripts); about half of the titles are accessible through a database and we are presenting here the first ca. 2000 with full information. Song: 21 Guns for Susie (Boom! Boom! Boom!) Year: 1934 Composer: Myers, Richard Lyricist: Silverman, Al; Leslie, Bob; Leslie, Ken Arranger: Mason, Jack Song: 33rd Division March Year: 1928 Composer: Mader, Carl Song: About a Quarter to Nine From: Go into Your Dance (movie) Year: 1935 Composer: Warren, Harry Lyricist: Dubin, Al Arranger: Weirick, Paul Song: Ace of Clubs, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Diamonds, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred Song: Ace of Spades, The Year: 1926 Composer: Fiorito, Ted Arranger: Huffer, Fred K. Song: Actions (speak louder than words) Year: 1931 Composer: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Lyricist: Vallee, Rudy; Himber, Richard; Greenblatt, Ben Arranger: Prince, Graham Song: Adios Year: 1931 Composer: Madriguera, Enric Lyricist: Woods, Eddie; Madriguera, Enric(Spanish translation) Arranger: Raph, Teddy Song: Adorable From: Adorable (movie) Year: 1933 Composer: Whiting, Richard A. Lyricist: Marion, George, Jr. Arranger: Mason, Jack; Rochette, J. (vocal trio) Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) Year: 1931 Composer: Lecuona, Ernesto Lyricist: Gilbert, L. Wolfe Arranger: Katzman, Louis Song: African Lament (Lamento Africano) -

2006 Was Another Year of Great Events, New Releases, and Accolades for and About Judy Garland’S Great Talent and Body of Work

2006 was another year of great events, new releases, and accolades for and about Judy Garland’s great talent and body of work. The biggest news for this past year was the discovery of two of the lost Decca recordings that Judy made in 1935. Thought to be lost forever, these recordings were transferred to digital format and put up for auction (see following page for details). The other big news for the year would have to be the highly successful release of the Judy Garland stamp on what would have been Judy’s 84th birthday, June 10, 2006 (see following page for details) June 2006 could well be remembered as the best “Judy Garland Month” ever! We had the stamp release, two new CDs, over 10 DVDs, the Judy Garland Festival in Minnesota, and more! Plus, The Judy Room has a new look! Beginning in Summer 2006, I began making “vintage magazine covers” the theme of the homepage (see the thumbnails below). These covers reflect the change in seasons and special events or holidays while also fondly looking back to golden age of fan magazines . A BIG THANK YOU to “Alex in Belgium” for his masterful photo colorization. I would like to extend a special thanks and appreciation to Eric Hemphill, Scott Schechter, “tinman”, Donald, and everyone else who has helped to make The Judy Room a success. I hope you all know that I couldn’t do this without you. THANK YOU! Sincerely, Scott Brogan The Judy Room JANUARY 12, 2006: The Recording Industry Association Of America (RIAA) announces their Grammy Hall Of Fame inductees, and the 1956 M-G-M Records soundtrack to The Wizard Of Oz is included. -

Theatre Archive Project Archive

University of Sheffield Library. Special Collections and Archives Ref: MS 349 Title: Theatre Archive Project: Archive Scope: A collection of interviews on CD-ROM with those visiting or working in the theatre between 1945 and 1968, created by the Theatre Archive Project (British Library and De Montfort University); also copies of some correspondence Dates: 1958-2008 Level: Fonds Extent: 3 boxes Name of creator: Theatre Archive Project Administrative / biographical history: Beginning in 2003, the Theatre Archive Project is a major reinvestigation of British theatre history between 1945 and 1968, from the perspectives of both the members of the audience and those working in the theatre at the time. It encompasses both the post-war theatre archives held by the British Library, and also their post-1968 scripts collection. In addition, many oral history interviews have been carried out with visitors and theatre practitioners. The Project began at the University of Sheffield and later transferred to De Montfort University. The archive at Sheffield contains 170 CD-ROMs of interviews with theatre workers and audience members, including Glenda Jackson, Brian Rix, Susan Engel and Michael Frayn. There is also a collection of copies of correspondence between Gyorgy Lengyel and Michel and Suria Saint Denis, and between Gyorgy Lengyel and Sir John Gielgud, dating from 1958 to 1999. Related collections: De Montfort University Library Source: Deposited by Theatre Archive Project staff, 2005-2009 System of arrangement: As received Subjects: Theatre Conditions of access: Available to all researchers, by appointment Restrictions: None Copyright: According to document Finding aids: Listed MS 349 THEATRE ARCHIVE PROJECT: ARCHIVE 349/1 Interviews on CD-ROM (Alphabetical listing) Interviewee Abstract Interviewer Date of Interview Disc no. -

National Delta Kappa Alpha

,...., National Delta Kappa Alpha Honorary Cinema Fraternity. 31sT ANNIVERSARY HONORARY AWARDS BANQUET honoring GREER GARSON ROSS HUNTER STEVE MCQUEEN February 9, 1969 TOWN and GOWN University of Southern California PROGRAM I. Opening Dr. Norman Topping, President of USC II. Representing Cinema Dr. Bernard R. Kantor, Chairman, Cinema III. Representing DKA Susan Lang Presentation of Associate Awards IV. Special Introductions Mrs. Norman Taurog V. Master of Ceremonies Jerry Lewis VI. Tribute to Honorary l\llembers of DKA VII. Presentation of Honorary Awards to: Greer Garson, Ross Hunter, Steve McQueen VIII. In closing Dr. Norman Topping Banquet Committee of USC Friends and Alumni Mrs. Tichi Wilkerson Miles, chairman Mr. Stanley Musgrove Mr. Earl Bellamy Mrs. Lewis Rachmil Mrs. Harry Brand Mrs. William Schaefer Mr. George Cukor Mrs. Sheldon Schrager Mrs. Albert Dorskin Mr. Walter Scott Mrs. Beatrice Greenough Mrs. Norman Taurog Mrs. Bernard Kantor Mr. King Vidor Mr. Arthur Knight Mr. Jack L. Warner Mr. Jerry Lewis Mr. Robert Wise Mr. Norman Jewison is unable to be present this evening. He will re ceive his award next year. We are grateful to the assistance of 20th Century Fox, Universal studios, United Artists and Warner Seven Arts. DEPARTMENT OF CINEMA In 1929, the University of Southern California in cooperation with the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences offered a course described in the Liberal Arts Catalogue as : Introduction to Photoplay: A general introduction to a study of the motion picture art and industry; its mechanical founda tion and history; the silent photoplay and the photoplay with sound and voice; the scenario; the actor's art; pictorial effects; commercial requirements; principles of criticism; ethical and educational features; lectures; class discussions, assigned read ings and reports. -

Memories from “CHITARRE ACUSTICHE D’ITALIA”

Art Phillips Music Design PO Box 219 Balmain NSW 2041 Tel: +61 2 9810-6611 Fax: +61 2 9810-6511 Cell: +61 (0) 407 225 811 ART PHILLIPS – memories from “CHITARRE ACUSTICHE D’ITALIA” Each of the songs included in “ Chitarre Acustiche d’Italia ” have been an important element for the music career of the two-time Emmy and APRA awarded artist composer Art Phillips (Arturo Di FIlippo). The Italian heritage of his father and grandfather and their love for music, drove Art into the music scene and inspired him to create, after more than 30 years of global success, a tribute album like this. This album is the story of Italian family memories and traditions. Below, Art Phillips explains the feelings and memories related to each track contained on the album. 1. Tra Veglia e Sonno (Between Wakefulness and Sleep) A piece I learnt from my father and grandfather in my very early years. They would play this every time they got together in my grandfathers kitchen with their guitar and mandolin, where live music would be an important part in our family life. Grandpa lived just around the corner from my home where our backyards connected, in fact he was also a carpenter and brick mason and built our home as well as all the other homes located around our block. Most of his children lived next door or just around the corner with connecting back yards. We would visit my grandpa and grandma each and every day, and there would not be many days in passing that my guitar wouldn’t join into the family’s musical moments. -

Austerity Fashion 1945-1951 Bethan Bide .Compressed

Austerity Fashion 1945-1951 rebuilding fashion cultures in post-war London Bethan Bide Royal Holloway, University of London Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Figure 1: Second-hand shoes for sale at a market in the East End, by Bob Collins, 1948. Museum of London, IN37802. 2 Declaration of authorship I Bethan Bide hereby declare that this thesis and the work presented in it is entirely my own. Where I have consulted the work of others, this is always clearly stated. Bethan Bide 8 September 2017 3 Abstract This thesis considers the relationship between fashion, austerity and London in the years 1945 to 1951—categorised by popular history as a period of austerity in Britain. London in the late 1940s is commonly remembered as a drab city in a state of disrepair, leading fashion historians to look instead to Paris and New York for signs of post-war energy and change. Yet, looking closer at the business of making and selling fashion in London, it becomes clear that, behind the shortages, rubble and government regulation, something was stirring. The main empirical section of the thesis is divided into four chapters that explore different facets of London’s fashionable networks. These consider how looking closely at the writing, making, selling and watching of austerity fashion can help us build a better understanding of London fashion in the late 1940s. Together, these chapters reveal that austerity was a driving force for dynamic processes of change— particularly in relation to how women’s ready-to-wear fashions were made and sold in the city—and that a variety of social, economic and political conditions in post- war Britain changed the way manufacturers, retailers and consumers understood the symbolic capital of London fashion.