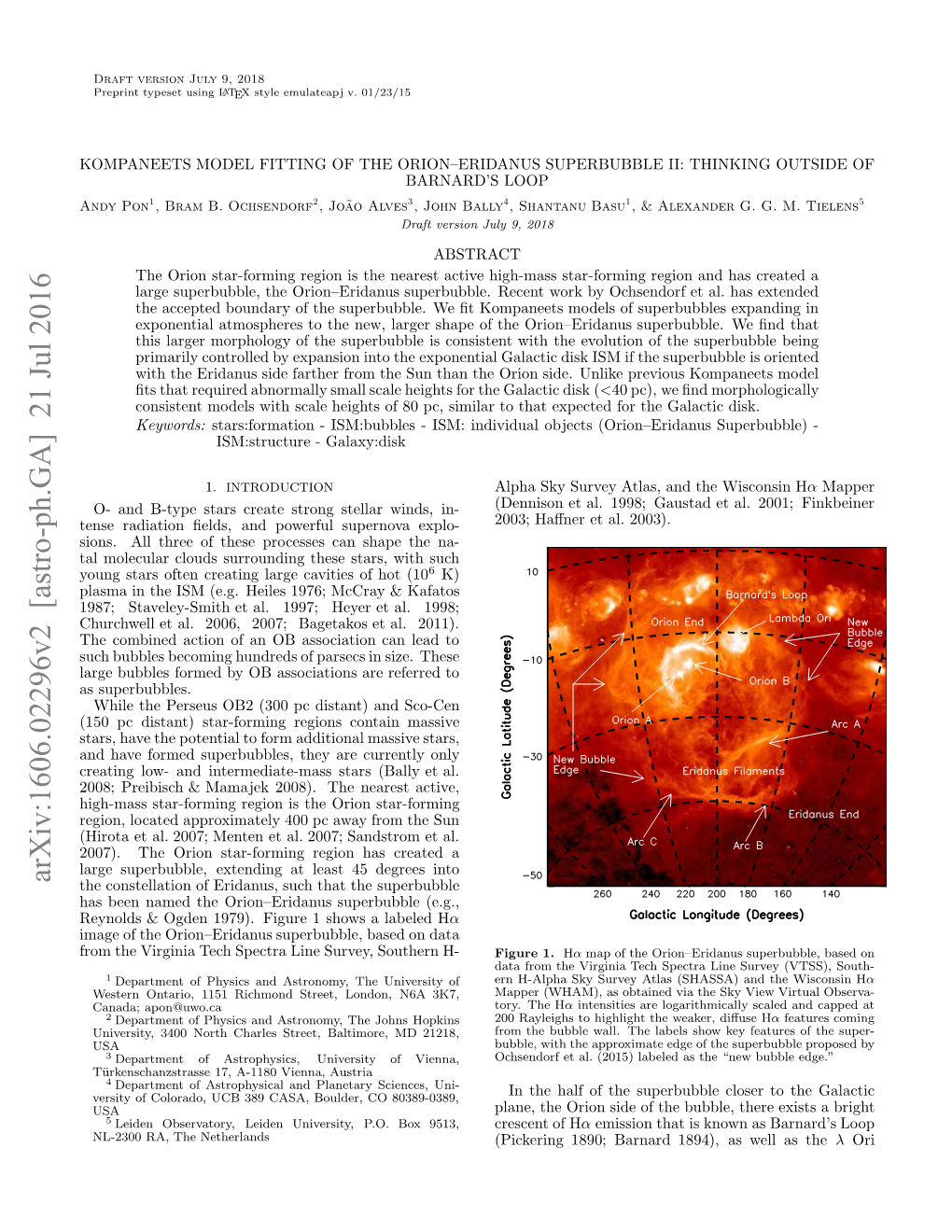

Arxiv:1606.02296V2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps

W here Are the Distant Worlds? Star Maps Abo ut the Activity Whe re are the distant worlds in the night sky? Use a star map to find constellations and to identify stars with extrasolar planets. (Northern Hemisphere only, naked eye) Topics Covered • How to find Constellations • Where we have found planets around other stars Participants Adults, teens, families with children 8 years and up If a school/youth group, 10 years and older 1 to 4 participants per map Materials Needed Location and Timing • Current month's Star Map for the Use this activity at a star party on a public (included) dark, clear night. Timing depends only • At least one set Planetary on how long you want to observe. Postcards with Key (included) • A small (red) flashlight • (Optional) Print list of Visible Stars with Planets (included) Included in This Packet Page Detailed Activity Description 2 Helpful Hints 4 Background Information 5 Planetary Postcards 7 Key Planetary Postcards 9 Star Maps 20 Visible Stars With Planets 33 © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Detailed Activity Description Leader’s Role Participants’ Roles (Anticipated) Introduction: To Ask: Who has heard that scientists have found planets around stars other than our own Sun? How many of these stars might you think have been found? Anyone ever see a star that has planets around it? (our own Sun, some may know of other stars) We can’t see the planets around other stars, but we can see the star. -

A Synchrotron Superbubble in the IC 10 Galaxy: a Hypernova Remnant?

Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 000, 1–?? (2007) Printed 28 October 2018 (MN LATEX style file v2.2) A synchrotron superbubble in the IC 10 Galaxy: a hypernova remnant? T. A. Lozinskaya1⋆ and A. V. Moiseev2 1Sternberg Astronomical Institute, Universitetskii pr. 13, Moscow, 119991 Russia 2Special Astrophysical Observatory, Nizhnii Arkhyz, Karachaevo-Cherkesia, 369167 Russia Accepted 2007 June 29. Received 2007 June; in original form 2007 June 4 ABSTRACT The nature of the synchrotron superbubble in the IC 10 galaxy is discussed using the results of our investigation of its ionized gas structure, kinematics, and emission spectrum from observations made with the 6-m telescope of the Special Astrophysical Observatory of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and based on our analysis of the radio emission of the region. The hypernova explosion is shown to be a more plausi- ble mechanism of the formation of the synchrotron superbubble compared with the earlier proposed model of multiple supernova explosions. A compact remnant of this hypernova may be identified with the well known X-ray binary X-1 – an accreting black hole. Key words: ISM: bubbles – ISM: kinematics and dynamics – supernova remnants galaxies: individual: IC 10. 1 INTRODUCTION. and observations with a scanning Fabry–Perot interferom- eter (FPI) in the Hα line. We report the detailed results The synchrotron superbubble in the IC 10 galaxy was discov- of our observations in a separate paper (Lozinskaya et al. ered by Yang & Skillman (1993). They associated it with the 2007). In this Letter we summarize the main results of these explosion of about ten supernovae. The synchrotron nature observations and the ensuing conclusions. -

H I Deficiency in Groups : What Can We Learn from Eridanus ?

Bull. Astr. Soc. India (2004) 32, 239{245 H i de¯ciency in groups : what can we learn from Eridanus ? A. Omar¤y Raman Research Institute, Sadashivanagar, Bangalore 560 080, India Received 14 July 2004; accepted 24 August 2004 Abstract. The H i content of the Eridanus group of galaxies is studied using the GMRT observations and the HIPASS data. A signi¯cant H i de¯ciency up to a factor of 2 ¡ 3 is observed in galaxies in the Eridanus group. The de¯ciency is found to be directly correlated with the projected galaxy density and inversely correlated with the line-of-sight radial velocity. It is suggested that the H i de¯ciency is due to tidal interactions. An important implication is that signi¯cant evolution of galaxies can take place in a group environment. Keywords : galaxies: ISM { galaxies: interactions { galaxies: kinematics and dynamics { galaxies: evolution { galaxies: clusters: individual: Eridanus group { radio lines: galaxies 1. Introduction Spiral galaxies in the cores of clusters are known to be H i de¯cient compared to their ¯eld counterparts (Davies and Lewis 1973, Giovanelli and Haynes 1985, Cayatte et al. 1990, Bravo-Alfaro et al. 2000). Several gas-removal mechanisms have been proposed to explain the H i de¯ciency in cluster galaxies. There are convincing results from both the simulations and the observations that ram-pressure stripping can be active in galaxies which have crossed the high ICM (Intra Cluster Medium) density region in the cores of clusters (Vollmer et al. 2001, van Gorkom 2003). However, it is not clear that all H i de¯cient galaxies have crossed the core. -

The Night Sky December

The Night Sky December Equipment you will need Because of the darkness of our forest locations, you can see many wonders of the night skies with your naked eye, although your eyes will Boötes need a good 20 minutes to adjust to the darkness. Any bright lights, such as that from your torch, will set them back again. You can reduce this effect by putting a red filter on your torch. Equipment worth investing in includes: Lynx • Binoculars – cheaper and easier to carry than a telescope. Look for ones with glass lenses. • Camera – to capture that fantastic star scene forever • Tripod – essential for use with your camera • Telescope – worth investing in for the really committed stargazer • Google Skymaps – a superb free app, available for Android and Delphinius iPhone. You point your phone towards the sky and it shows you the constellations and identifies the stars using inbuilt GPS Lepus Getting started – your first 5 constellations to spot • Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) has been used by sailors since ancient times to locate the fixed-point Pole Star and navigate home • Leo (the lion) is it a lion, as the Greeks decided? Or is it K9 from Doctor Who? • Cassiopeia (the queen of Aethiopia) is one of the easiest constellations to locate and looks like a huge W, almost directly overhead • Cepheus (the king of Aethiopia) is one of 48 constellations Eridanus identified by 2nd century astronomer Ptolemy. Imagine a child’s drawing of a house, complete with roof • Orion (the hunter), with belt and sword, is perhaps the most famous constellation – and one of the few that actually bears some slight resemblance to its namesake Stargazing facts for kids • You can see the International Space Station without using binoculars, and you can track it moving across the sky • The sun is 300,000 times bigger than earth and 93 million miles Boötes Lynx Delphinus Lepus Eridanus away. -

Breaching the Eddington Limit in the Most Massive, Most Luminous Stars

Mass Loss from (Hot) Massive Luminous Stars Stan Owocki Bartol Research Institute Department of Physics & Astronomy University of Delaware Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Massive Stars in the Whirlpool Galaxy Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Henize 70: LMC SuperBubble Wind-Blown Bubbles in ISM Some key scalings: Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Henize 70: LMC SuperBubble Wind-Blown Bubbles in ISM Some key scalings: WR wind bubble NGC 2359 Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Henize 70: LMC SuperBubble Wind-Blown Bubbles in ISM Some key scalings: WR wind bubble NGC 2359 Superbubble in the Large Magellanic Cloud Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Pistol Nebula Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Eta Carinae Wednesday, January 12, 2011 P-Cygni Line Profile Line-scattering in massive winds Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Observed wind line profiles Resonance line-scattering Recombination line O-star P-Cygni profile WR-star emission profile −v∞ +v −v∞ ∞ Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Basic Mass Loss Properties i 2 Mass Loss rate M = 4πρvr Terminal speed Velocity law v(r) v∞ 8 Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Massive-Star Mass Loss i M 1. OB Winds M ~ 10−9 − 10−6 yr v∞ 1000 − 3000 km / s – opt. thin τ c < 1 2. Wolf-Rayet Winds i M M ~ 10−6 − 10−5 yr – opt. thick τ c > 1 v∞ 1000 − 3000 km / s 3. Luminous Blue Variable (LBV) Eruptions i 1 −5 M -very opt. thick τ c M ~ 10 − 1 !! yr v∞ 50 − 1000 km / s Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Q: What can drive such extreme mass loss?? Wednesday, January 12, 2011 Q: What can drive such extreme mass loss?? A: The force of light! Wednesday, January 12, 2011 -

Modelling Supernova Remnant Kinematics and X-Ray Emission: Some Examples

Modelling Supernova Remnant kinematics and X-ray emission: Some Examples. Margarita Rosado Instituto de Astronomía UNAM Collaborators: • Pablo Velázquez, Ary Rodríguez González (ICN-UNAM) • Jorge Reyes Iturbide (IT Santiago Tianguistengo) • Patricia Ambrocio-Cruz (UAEH) • Mónica Sánchez-Cruces (ESFM-IPN) I. The Kinematics: By means of a FP Interferometer (i.e. the PUMA) One gets millions of Halpha or [SII] profiles over the field. From Valdez- Gutiérrez et al. 2001 OAN: San Pedro Mártir, B.C. Mexico PUMA INTERFEROMETER PUMA parameters - Detector CCD 1024x1024 – FP scanning steps 48 – Finesse 24 – Spectral resolution 47.3 km s-1 – Plate scale 0.59 arcsec pix -1 – Filters Hα [SII] – Central lambda a 6570 6720 – Interference order 330 332 – Free spectral range b 847 931 – Sampling step c 17.6 19.4 – Calibration line a Hα (6562.7) Ne (6717.04) a) in units of angstroms, b) in km s -1, c) in km s -1 channel -1 Doppler Effect Iso-velocity contours in our Galaxy Rotation curve of our Galaxy (also from Bland & Blitz ) The kinematics of SNRs is a powerful tool that we can use to estimate the DISTANCE, and other important parameters of those objects. The Galactic SNR CTB 109 and the quest for its distance: Radio Einstein X-rays continuum, and CO CO and HI From Gregory & Falman (1980), Tatematsu et al. (1987), Kothes et al. (2002, 2006) While in the optical: Hurford & Fesen (1995) Sánchez -Cruces et al. (2017) 2D [SII]/Hα line-ratios of the optical filaments è a radiative shock Typical [SII] velocity profiles of two regions: è SNR CTB 109 IS IN THE PERSEUS ARM è THIS SNR HOSTING A MAGNETAR HAS RATHER TYPICAL INITIAL ENERGY II. -

Feedback by Massive Stars and the Emergence of Superbubbles

Astronomy & Astrophysics manuscript no. krause+2013_ESB_II_v10 c ESO 2018 January 3, 2018 Feedback by massive stars and the emergence of superbubbles II. X-ray properties Martin Krause1, 2,⋆, Roland Diehl1, 2, Hans Böhringer1, 2, Michael Freyberg1, and Daniel Lubos1 1 Max-Planck-Institut für extraterrestrische Physik, Giessenbachstr. 1, 85741 Garching, Germany 2 Excellence Cluster Universe, Technische Universität München, Boltzmannstrasse 2, 85748 Garching, Germany Received March 24, 2014; accepted ? ABSTRACT Context. In a previous paper we investigated the energy transfer of massive stars to the interstellar medium as a function of time and the geometrical configuration of three massive stars via 3D-mesh-refining hydrodynamics simulations, following the complete evolution of the massive stars and their supernovae except non-thermal processes . Aims. In order to compare our results against observations we derive thermal X-ray properties of the interstellar medium from our simulations and compare them to observations of superbubbles in general, to the well-studied nearby Orion-Eridanus superbubble and to the diffuse soft X-ray emission of nearby galaxies. Methods. We analysed our ISM simulation results with the help of spectra for plasma temperatures between 0.1 and 10 keV and computed the spectral evolution and the spatio-temporal distribution of the hot gas. Results. Despite significant input of high temperature gas from supernovae and fast stellar winds, the resulting thermal X-ray spectra are generally very soft, with most of the emission well below 1 keV. We show that this is due to mixing triggered by resolved hydrodynamic instabilities. Supernovae enhance the X-ray luminosity of a superbubble by 1-2 orders of magnitude for a time span of about 0.1 Myr; longer if a supernova occurs in a larger superbubble and shorter in higher energy bands. -

A Guide to Star Names, Pronunciations, and Related Constellations

Astronomy Club of Asheville 3 Feb. 2020 version Page 1 of 8 A Guide to Star Names, Pronunciations, and Related Constellations Proper Star Names: There are over 300 proper star names that are used and accepted worldwide today -- and approved by the International Astronomical Union. Most of them come from the ancient Arabic cultures, but there are many star names in common use from the Greek, the Roman, European, and other cultures as well. On the pages below you will find an alphabetical list of many, but not all, of the proper star names, their pronunciations, and related constellations. Find a list of star names by constellation at this web link. Find another list of common star names at this web link. Star Catalogs that are Currently Used by Astronomers 1. Bayer Catalog: This first widely recognized star catalog was published by German astronomer Johann Bayer in 1603. This list of naked-eye stars indexes the stars in each constellation, using the letters of the Greek alphabet, followed by the genitive form of its parent constellation's Latin name, e.g., alpha Orionis. Typically, the brightest star in each constellation received the first Greek letter (alpha), the second brightest star the second letter (beta), and on-and-on. But you will often notice that the Bayer sequencing of the bright stars in the constellations is not true to what we see and know today about their apparent brightness. Original errors in the brightness estimates, along with the brightness variability of the stars (like Betelgeuse in Orion), have caused the Bayer sequencing not to match the stellar brightness that we observe today. -

Forming a Constant Density Medium Close to Long Gamma-Ray Bursts

A&A 460, 105–116 (2006) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361:20065709 & c ESO 2006 Astrophysics Forming a constant density medium close to long gamma-ray bursts A. J. van Marle1,N.Langer1, A. Achterberg1, and G. García-Segura2 1 Astronomical Institute, Utrecht University, PO Box 80000, 3508 TA, Utrecht, The Netherlands e-mail: [A.vanMarle;N.Langer;A.Achterberg]@astro.uu.nl 2 Instituto de Astronomía-UNAM, APDO Postal 877, Ensenada, 22800 Baja California, Mexico e-mail: [email protected] Received 29 May 2006 / Accepted 21 July 2006 ABSTRACT Aims. The progenitor stars of long Gamma-Ray Bursts (GRBs) are thought to be Wolf-Rayet stars, which generate a massive and energetic wind. Nevertheless, about 25 percent of all GRB afterglows light curves indicate a constant density medium close to the exploding star. We explore various ways to produce this, by creating situations where the wind termination shock arrives very close to the star, as the shocked wind material has a nearly constant density. Methods. Typically, the distance between a Wolf-Rayet star and the wind termination shock is too large to allow afterglow formation in the shocked wind material. Here, we investigate possible causes allowing for a smaller distance: A high density or a high pressure in the surrounding interstellar medium (ISM), a weak Wolf-Rayet star wind, the presence of a binary companion, and fast motion of the Wolf-Rayet star relative to the ISM. Results. We find that all four scenarios are possible in a limited parameter space, but that none of them is by itself likely to explain the large fraction of constant density afterglows. -

Supernova Star Maps

Supernova Star Maps Which Stars in the Night Sky Will Go Su pernova? About the Activity Allow visitors to experience finding stars in the night sky that will eventually go supernova. Topics Covered Observation of stars that will one day go supernova Materials Needed • Copies of this month's Star Map for your visitors- print the Supernova Information Sheet on the back. • (Optional) Telescopes A S A Participants N t i d Activities are appropriate for families Cre with children over the age of 9, the general public, and school groups ages 9 and up. Any number of visitors may participate. Location and Timing This activity is perfect for a star party outdoors and can take a few minutes, up to 20 minutes, depending on the Included in This Packet Page length of the discussion about the Detailed Activity Description 2 questions on the Supernova Helpful Hints 5 Information Sheet. Discussion can start Supernova Information Sheet 6 while it is still light. Star Maps handouts 7 Background Information There is an Excel spreadsheet on the Supernova Star Maps Resource Page that lists all these stars with all their particulars. Search for Supernova Star Maps here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov/download-search.cfm © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Star Maps: Stars likely to go Supernova! Leader’s Role Participants’ Role (Anticipated) Materials: Star Map with Supernova Information sheet on back Objective: Allow visitors to experience finding stars in the night sky that will eventually go supernova. -

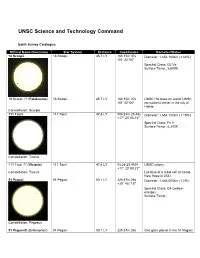

UNSC Science and Technology Command

UNSC Science and Technology Command Earth Survey Catalogue: Official Name/(Common) Star System Distance Coordinates Remarks/Status 18 Scorpii {TCP:p351} 18 Scorpii {Fact} 45.7 LY 16h 15m 37s Diameter: 1,654,100km (1.02R*) {Fact} -08° 22' 06" {Fact} Spectral Class: G2 Va {Fact} Surface Temp.: 5,800K {Fact} 18 Scorpii ?? (Falaknuma) 18 Scorpii {Fact} 45.7 LY 16h 15m 37s UNSC HQ base on world. UNSC {TCP:p351} {Fact} -08° 22' 06" recruitment center in the city of Halkia. {TCP:p355} Constellation: Scorpio 111 Tauri 111 Tauri {Fact} 47.8 LY 05h:24m:25.46s Diameter: 1,654,100km (1.19R*) {Fact} +17° 23' 00.72" {Fact} Spectral Class: F8 V {Fact} Surface Temp.: 6,200K {Fact} Constellation: Taurus 111 Tauri ?? (Victoria) 111 Tauri {Fact} 47.8 LY 05:24:25.4634 UNSC colony. {GoO:p31} {Fact} +17° 23' 00.72" Constellation: Taurus Location of a rebel cell at Camp New Hope in 2531. {GoO:p31} 51 Pegasi {Fact} 51 Pegasi {Fact} 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Diameter: 1,668,000km (1.2R*) {Fact} +20° 46' 7.8" {Fact} Spectral Class: G4 (yellow- orange) {Fact} Surface Temp.: Constellation: Pegasus 51 Pegasi-B (Bellerophon) 51 Pegasi 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Gas giant planet in the 51 Pegasi {Fact} +20° 46' 7.8" system informally named Bellerophon. Diameter: 196,000km. {Fact} Located on the edge of UNSC territory. {GoO:p15} Its moon, Pegasi Delta, contained a Covenant deuterium/tritium refinery destroyed by covert UNSC forces in 2545. {GoO:p13} Constellation: Pegasus 51 Pegasi-B-1 (Pegasi 51 Pegasi 50.1 LY 22h:57m:28s Moon of the gas giant planet 51 Delta) {GoO:p13} +20° 46' 7.8" Pegasi-B in the 51 Pegasi star Constellation: Pegasus system; a Covenant stronghold on the edge of UNSC territory. -

The Fundamentals of Stargazing Sky Tours South

The Fundamentals of Stargazing Sky Tours South 01 – The March Sky Copyright © 2014-2016 Mintaka Publishing Inc. www.CosmicPursuits.com -2- The Constellation Orion Let’s begin the tours of the deep-southern sky with the most famous and unmistakable constellation in the heavens, Orion, which will serve as a guide for other bright constellations in the southern late-summer sky. Head outdoors around 8 or 9 p.m. on an evening in early March, and turn towards the north. If you can’t find north, you can ask someone else, or get a small inexpensive compass, or use the GPS in your smartphone or tablet. But you need to face at least generally northward before you can proceed. You will also need a good unobstructed view of the sky in the north, so you may need to get away from structures and trees and so on. The bright stars of the constellation Orion (in this map, south is up and east is to the right) And bring a pair of binoculars if you have them, though they are not necessary for this tour. Fundamentals of Stargazing -3- Now that you’re facing north with a good view of a clear sky, make a 1/8th of a turn to your left. Now you are facing northwest, more or less. Turn your gaze upward about halfway to the point directly overhead. Look for three bright stars in a tidy line. They span a patch of sky about as wide as your three middle fingers held at arm’s length. This is the “belt” of the constellation Orion.