Improving the Root Vegetables

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rhubarb Asheville

RHUBARB TAKE-AWAY MENU SNACKS Asparagus, English Peas 7 Comeback Sauce 5 Blue Cheese, BBQ Salt 7.5 House-Made Saltines, Bread & Butter Pickles 7 Chapata Toast, Red Onion Jam, Strawberry-Green Peppercorn Compote, Crispy Shallots 12 E Y V Benton’s Bacon 6.5 Mimosa Egg, Sauce Gribiche, Ramp Breadcrumbs, Pickled Red Onion 10 LG Feta, Pecans, Shaved Vegetables, Strawberry-Banyuls Vinaigrette 12 Flageolet Beans, Local Mushrooms, Tuscan Kale, Fennel Tops, Breadcrumbs 17 SANDWICHES Seared Double Beef & Bacon Patty, B&B Pickles, French Fries 11.5 - Add House Pimiento Cheese, Ashe County Cheddar or Ashe County Gouda 2 Gouda, Spiced Green Tomatoes, Radicchio, Sweet Potato Brioche, French Fries 11.5 Pepper-Vinegar BBQ Sauce, Chow-Chow, Brioche Bun, French Fries 13.5 ENTREES Dandelion Greens, Fennel Confit, Hoppin’ John, Fennel Pesto, Pickled Fennel 24 Pea and Carrot Potage, Asparagus, Herb Salad 23 20 Spring Risotto, Asparagus, Peas, Ramps, Parsley Root, Sorrel Pistou 23 Farm & Sparrow Grits, Garlic Confit, Hearty Greens, Breadcrumbs 18 Roasted Red Bliss Potatoes, Green Garlic, Spinach, Wild Ramps, GG Parsley Chermoula 23 Roasted Rutabaga, Rapini, House Steak Sauce, Pickled Radish 24 Dessert CHILDREN’s MENU Whipped Cream 6 5 Streusel Topping 6 5 5 NON-ALCOHOLIC (1L) 6 3 2 Beer WINE Jean-Luc Joillot, Crémant De Bourgogne Brut, Burgundy, France NV 20 375ml Clara Vie, Brut, Crémant de Limoux, Languedoc-Roussillon, France NV 22 Miner, Simpson Vineyard, Viognier, Napa Valley, California 2017 16 375ml Mayu, Huanta Vineyard, Pedro Ximenez, Valle De Elqui, -

Rutabagas Michigan-Grown Rutabagas Are Available Late September Through November

Extension Bulletin HNI52 • October 2012 msue.anr.msu.edu/program/info/mi_fresh Using, Storing and Preserving Rutabagas Michigan-grown rutabagas are available late September through November. Written by: Katherine E. Hale MSU Extension educator Recommended • Use rutabagas in soups or stew, or bake, boil or steam and slice or varieties mash as a side dish. Lightly stir- American Purple Top, Thomson fry or eat raw in salads. Rutabaga Laurentian and Joan is traditional in Michigan pasties, along with potatoes, carrots and Interesting facts beef. • Harvest when they reach the size • Rutabaga belongs to the of a softball. You may harvest Cruciferae or mustard family and rutabagas as they reach edible size the genus Brassica, classified as and throughout the season since Brassica napobrassica. they will keep in the ground. • Developed during the Middle Ages, rutabagas are thought to be a cross between Storage and food safety the turnip and the cabbage. • Wash hands before and after handling fresh fruits and • The rutabaga is an excellent source of vitamin C and vegetables. potassium, and a good source for fiber, thiamin, vitamin B6, calcium, magnesium, vitamin A and manganese. • Rutabagas will keep for months in a cool storage place. They store well in plastic bags in a refrigerator or cold cellar. • Similar to the turnip but sweeter, rutabagas are inexpensive and low in calories. • Keep rutabagas away from raw meat and meat juices to prevent cross contamination. Tips for buying, preparing • Before peeling, wash rutabagas using cool or slightly warm and harvesting water and a vegetable brush. • Look for smooth, firm vegetables with a round shape. -

Rutabaga Volume 1 • Number 12

Rutabaga Volume 1 • Number 12 What’s Inside l What’s So Great about Rutabaga? l Selecting and Storing Rutabaga l Varieties of Rutabaga l Fitting Rutabaga into MyPyramid l Recipe Collection l Grow Your Own Rutabaga l Activity Alley What’s So Great about Rutabaga? ; Rutabagas are an excellent source of vitamin C, and a good source of potassium, fiber and vitamin A. ; Rutabagas are low in calories and are fat free. ; Rutabaga’s sweet, mildly peppery flesh makes great side dishes. ; Rutabagas are tasty in salads, soups, and stews. Rutabagas are inexpensive. Selecting and Storing Rutabaga Rutabagas are available all year. But these root vegetables are Why is Potassium best in the fall. Rutabagas are often trimmed of taproots and tops. Important? When found in the grocery store, they are coated with clear wax to prevent moisture loss. Eating a diet rich in potassium and lower in sodium is Look for good for your health. Potassium is an electrolyte that Firm, smooth vegetables with a round, oval shape. Rutabagas helps keep body functions normal. It may also help pro- should feel heavy for their size. tect against high blood pressure. Potassium is found in fruits and vegetables. Avoid Avoid rutabagas with punctures, deep cuts, cracks, or decay. Root vegetables like rutabagas are good sources of potassium. Most adults get adequate amounts of potas- Storage sium in their diet. To be sure you are eating enough, go Rutabagas keep well. Refrigerate in a to www.MyPyramid.gov to see how many fruits and plastic bag for two weeks or more. -

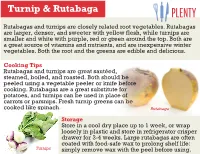

Turnip & Rutabaga

Turnip & Rutabaga Rutabagas and turnips are closely related root vegetables. Rutabagas are larger, denser, and sweeter with yellow flesh, while turnips are smaller and white with purple, red or green around the top. Both are a great source of vitamins and nutrients, and are inexpensive winter vegetables. Both the root and the greens are edible and delicious. Cooking Tips Rutabagas and turnips are great sautéed, steamed, boiled, and roasted. Both should be peeled using a vegetable peeler or knife before cooking. Rutabagas are a great substitute for potatoes, and turnips can be used in place of carrots or parsnips. Fresh turnip greens can be cooked like spinach. Rutabaga Storage Store in a cool dry place up to 1 week, or wrap loosely in plastic and store in refrigerator crisper drawer for 3-4 weeks. Large rutabagas are often coated with food-safe wax to prolong shelf life: Turnips simply remove wax with the peel before using. Quick Shepherd’s Pie Ingredients: • 1 lb rutabaga or turnip (or both) • ¼ cup low-fat milk • 2 tbsp butter • ½ tsp salt • ½ tsp pepper • 1 tbsp oil (olive or vegetable) • 1 lb ground lamb or beef • 1 medium onion, finely chopped • 3-4 carrots, chopped (about 2 cups) • 3 tbsp oregano • 3 tbsp flour • 14 oz chicken broth (reduced sodium is best) • 1 cup corn (fresh, canned, or frozen) Directions: 1. Chop the rutabaga/turnip into one inch cubes. 2. Steam or boil for 8-10 minutes, or until tender. 3. Mash with butter, milk, and salt and pepper. Cover and set aside. 4. Meanwhile, heat oil in a skillet over medium-high heat. -

Recipe List by Page Number

1 Recipes by Page Number Arugula and Herb Pesto, 3 Lemon-Pepper Arugula Pizza with White Bean Basil Sauce, 4 Shangri-La Soup, 5 Summer Arugula Salad with Lemon Tahini Dressing, 6 Bok Choy Ginger Dizzle, 7 Sesame Bok Choy Shiitake Stir Fry, 7 Bok Choy, Green Garlic and Greens with Sweet Ginger Sauce, 8 Yam Boats with Chickpeas, Bok Choy and Cashew Dill Sauce, 9 Baked Broccoli Burgers, 10 Creamy Dreamy Broccoli Soup, 11 Fennel with Broccoli, Zucchini and Peppers, 12 Romanesco Broccoli Sauce, 13 Stir-Fry Toppings, 14 Thai-Inspired Broccoli Slaw, 15 Zesty Broccoli Rabe with Chickpeas and Pasta, 16 Cream of Brussels Sprouts Soup with Vegan Cream Sauce, 17 Brussels Sprouts — The Vegetable We Love to Say We Hate, 18 Roasted Turmeric Brussels Sprouts with Hemp Seeds on Arugula, 19 Braised Green Cabbage, 20 Cabbage and Red Apple Slaw, 21 Cabbage Lime Salad with Dijon-Lime Dressing, 22 Really Reubenesque Revisited Pizza, 23 Simple Sauerkraut, 26 Chipotle Cauliflower Mashers, 27 Raw Cauliflower Tabbouleh, 28 Roasted Cauliflower and Chickpea Curry, 29 Roasted Cauliflower with Arugula Pesto, 31 Collard Green and Quinoa Taco or Burrito Filling, 32 Collard Greens Wrapped Rolls with Spiced Quinoa Filling, 33 Mediterranean Greens, 34 Smoky Collard Greens, 35 Horseradish and Cannellini Bean Dip, 36 Kale-Apple Slaw with Goji Berry Dressing, 37 Hail to the Kale Salad, 38 Kid’s Kale, 39 The Veggie Queen’s Husband’s Daily Green Smoothie, 40 The Veggie Queen’s Raw Kale Salad, 41 Crunchy Kohlrabi Quinoa Salad, 42 Balsamic Glazed Herb Roasted Roots with Kohlrabi, -

Black Leg, Light Leaf Spot and White Leaf Spot in Crucifers

A CLINIC CLOSE-UP Black Leg, Light Leaf Spot, and White Leaf Spot in Western Oregon Oregon State University Extension Service January 2016 A number of foliar fungal diseases can affect crucifer crops. Three fungal pathogens have emerged recently in western Oregon where epidemics of black leg, light leaf spot, and white leaf spot have been occurring since 2014. Black leg has been detected sporadically in Oregon since the 1970’s but historically black leg has caused significant problems wherever crucifers were grown. Crucifer seed rules have been in place within Oregon, Washington, and other markets to protect crucifer crops from black leg. Light leaf spot is new to North America, but has been reported in other regions of the world where it is known to cause significant seed yield losses of winter oilseed rape. Light leaf spot and black leg can both result in reduced yields or quality, depending on disease incidence and severity in vegetable and seed fields. White leaf spot has been previously reported in the US, but management has not normally been needed except in the southeastern US. White leaf spot may be less of an economic threat to crucifer production in the Pacific Northwest, compared to the risks from black leg and light leaf spot. The complete host range for these three diseases is not known at this time but it is likely that all Brassica and Raphanus crops grown in the Pacific Northwest are susceptible to some degree. These three diseases may be found on volunteer Brassica, Raphanus, and Sinapis species as well as crucifer weed species including little bittercress (Cardamine oligosperma), western yellowcress (Rorippa curvisiliqua), field pennycress (Thlaspi arvense), wild radish (Raphanus sativus), shepherd’s purse (Capsella bursa-pastoris), hedge mustard (Sisymbrium officinale), and field mustard or birdsrape mustard (Brassica rapa var. -

Brassica Napus Var

Genome Genetics and molecular mapping of resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8 in rutabaga (Brassica napus var. napobrassica) Journal: Genome Manuscript ID gen-2016-0034.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the Author: 04-May-2016 Complete List of Authors: Hasan, Muhammad Jakir; University of Alberta, Department of Agricultural, Food and NutritionalDraft Science Rahman, M. H.; Univ Alberta, Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science Keyword: Brassica napus, Rutabaga, Canola, Clubroot resistance, Mapping https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/genome-pubs Page 1 of 36 Genome Genetics and molecular mapping of resistance to Plasmodiophora brassicae pathotypes 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8 in rutabaga ( Brassica napus var. napobrassica ) Muhammad Jakir Hasan and Habibur Rahman M. J. Hasan, and H. Rahman. Department of Agricultural, Food and Nutritional Science, University of Alberta, 4-10 Agriculture/Forestry Centre, Edmonton, AB, T6G 2P5, Canada Corresponding author : Habibur Rahman (e-mail: [email protected]) Draft 1 https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/genome-pubs Genome Page 2 of 36 Abstract: Clubroot disease, caused by Plasmodiophora brassicae , is a threat to the production of Brassica crops including oilseed B. napus . In Canada, several pathotypes of this pathogen, such as pathotype 2, 3, 5, 6 and 8, were identified, and resistance to these pathotypes was found in a rutabaga ( B. napus var. napobrassica ) genotype. In this paper, we report the genetic basis and molecular mapping of this resistance by use of F 2, backcross (BC1) and doubled haploid (DH) populations generated from crossing of this rutabaga line to a susceptible spring B. napus canola line. -

Remarks on Brassica

International Journal of AgriScience Vol. 3(6): 453-480, June 2013 www.inacj.com ISSN: 2228-6322© International Academic Journals The wild and the grown – remarks on Brassica Hammer K.¹*, Gladis Th.¹ , Laghetti G.² , Pignone D.² ¹Former Institute of Crop Science, University of Kassel, Witzenhausen, Germany. * Author for correspondence (email: [email protected]) ²CNR – Institute of Plant Genetics, Bari, Italy. Received mmmm yyyy; accepted in revised form mmmmm yyyy ABSTRACT Brassica is a genus of the Cruciferae (Brassicaceae). The wild races are concentrated in the Mediterranean area with one species in CE Africa (Brassica somaliensis Hedge et A. Miller) and several weedy races reaching E Asia. Amphidiploid evolution is characteristic for the genus. The diploid species Brassica nigra (L.) Koch (n = 8), Brassica rapa L. emend. Metzg. (n = 10, syn.: B. campestris L.) and Brassica oleracea L. (n = 9) all show a rich variation under domestication. From the naturally occurring amphidiploids Brassica juncea (L.) Czern. (n = 18), Brassica napus L. emend. Metzg. (n = 19) and the rare Brassica carinata A. Braun (n = 17) also some vegetable races have developed. The man-made Brassica ×harmsiana O.E. Schulz (Brassica oleracea × Brassica rapa, n = 29, n = 39), or similar hybrids, serve also for the development of new vegetables. Brassica tournefortii Gouan (n = 10) from another Brassica- cytodeme, different from the Brassica rapa group, is occasionally grown as a vegetable in India. Brassica has developed two hotspots under cultivation, in the Mediterranean area and in E Asia. Cultivation by man has changed the different Brassica species in a characteristic way. The large amount of morphologic variation, which exceeded in many cases variations occurring in distinct wild species, has been observed by the classical botanists by adding these variations to their natural species by using Greek letters. -

Non-Starchy Vegetables Fat-Burning Non-Starchy Vegetables

WEIGHT LOSS GUIDELINES NON-STARCHY VEGETABLES FAT-BURNING NON-STARCHY VEGETABLES Alfalfa sprouts Dill pickles Pepproncinis Artichoke Eggplant Portabello mushrooms Artichoke hearts Endive Purslane Arugula Escarole Radicchio Asparagus Fennel Radishes Avocado Garlic Rapini Baby bok choy Ginger Red cabbage Baby corn Green beans Romaine Bamboo shoots Green onions Rutabaga Bean sprouts Hearts of palm Sauerkraut Bell peppers (all) Herbs (thyme, parsley, Scallions Bok choy basil, cilantro, rosemary, Seaweed (all) dill, sage, mint, Broccoli Shallots lemongrass, wasabi) Broccolini Snap peas Horseradish Brussels sprouts Snow peas Hot peppers (all– as Cabbage (all) Spaghetti squash much as you can handle, Cactus leaf hot stuff!) Spinach Carrots, raw (cooked Iceberg lettuce Summer squash carrots are starchy) Italian beans Swiss chard Cauliflower Jalapeno peppers Tomatillos Celery Jicama Tomato Chayote Kale (all) Turnip greens Chicory Kimchi Turnips Chinese cabbage Kohlrabi Water chestnuts Collard greens Leeks Watercress Crookneck squash Lettuce(all) Wax beans Cucumber Mushrooms (all) Yard-long beans Cushaw squash Mustard greens Yellow squash Daikon radish Okra Zucchini Dandelion greens Olives Dark leafy greans (ALL Onions are your friends!) Weight Loss Coach: 1.800.273.1686 x4 WEIGHT LOSS GUIDELINES STARCHY VEGETABLES IT’S NOT THAT THESE VEGGIES ARE BAD FOR YOU. YOU’LL FIND SOME OF THEM IN OUR WONDERFUL VEGGIE BLENDS– IN PERFECT PORTIONS TO PROMOTE WEIGHT LOSS AND KEEP YOU SATISFIED. WE JUST RECOMMEND NOT ADDING ANY MORE OF THESE VEGGIES TO YOUR PROGRAM -

DM3-Monfort.Pdf (430.4Kb)

2007 Extension Research Report Disease Management EVALUATION OF BRASSICA COVER CROPS FOR CONTROL OF SOILBORNE PEST AND DISEASES ON SUBSEQUENT SQUASH W. S. Monfort, A. S. Csinos, A. R. Barrentine, and Lara Lee Hickman, University of Georgia- Department of Plant Pathology, P. O. Box 748, Tifton, GA 31793 Introduction Roundup Ultramax (glyphosate) and removed. Many plants in the Brassicaceae family Using the same treatment design from the produce glucosinolates naturally. previous crop, Vapam (metam sodium) was Glucosinolates degrade into compounds such as drip-applied at 50 gal/A in the wheat treatment methyl isothiocyanates (MITC) and allyl on 31 July prior to planting. Plastic covered isothiocyanates (AITC). plots were 25 feet long and 30 inches wide. Both MITC and AITC are lethal to Squash cv. “Prelude II”seedlings were soilborne pests such as nematodes and fungi. In purchased from Lewis Taylor Farms in Tifton. fact, the common fumigant metham sodium A single plant was transplanted using a degrades to MITC and then accounts for its mechanical type transplanter, which cuts holes activity as a soil fumigant. Since the Brassica in the in the plastic just ahead of the planters in species have been demonstrated to produce the center of the plastic bed adjacent to the drip glucosinolates which degrade into MITC and tape on 16 August. Plant spacing was 12 inches. AITC there is interest in determining if the All plots were injected with Admire (4oz/A on growing a Brassica crop prior to another crop 18 August) and sprayed with Phaser (1 Qt/A on susceptible to soilborne pests would benefit 25 August, and 5, 11, 18, and 25 September), from the rotation. -

Tucson Community Supported Agriculture Newsletter 317 ~ December 5, 2011 ~ Online At

Tucson Community Supported Agriculture Newsletter 317 ~ December 5, 2011 ~ Online at www.TucsonCSA.org Fall 2011 Harvest list is online NEWS FROM THE FARM We are getting wonderful greens right now. But we’ll be getting other things too very soon. New crops are just a bit late maturing. But more potatoes are almost ready to be harvested. The Back Page And in a few weeks we’ll start getting green onions, broccoli, beets, carrots, squash and more. Baked Greens “Chips” THE LAST OF BLACK MESA RANCH HOLIDAY CANDY Easy Minestrone Soup Rutabaga Fries Don’t forget to check our holiday goodies from Black Mesa Ranch. They are only available Turnip or Radish Fritters-variation between Thanksgiving and Christmas. Our last order arrives this week, since next week is the last pickup week before our holiday break. We have truly awesome chocolate candy and Many more recipes in special seasonal goat cheeses. our online recipe archive RUTABAGAS The rutabaga (Brassica napobrassica), a relatively newcomer in the Daikon and Turnip Greens world of cruciferous vegetables, is thought to have evolved from a cross between a wild cabbage and a turnip. The earliest records of The greens of your daikon radishes rutabaga’s existence are from the seventeenth century in Southern and turnips are very edible and can be Europe, where they were both eaten by people and used for animal used like any leafy greens. In fact, fodder. Because rutabagas thrive best in colder climates, they became many people favor turnip greens over popular in Scandinavia, and especially in Sweden, which earned them the turnip themselves. -

Brassica Spp.) – 151

II.3. BRASSICA CROPS (BRASSICA SPP.) – 151 Chapter 3. Brassica crops (Brassica spp.) This chapter deals with the biology of Brassica species which comprise oilseed rape, turnip rape, mustards, cabbages and other oilseed crops. The chapter contains information for use during the risk/safety regulatory assessment of genetically engineered varieties intended to be grown in the environment (biosafety). It includes elements of taxonomy for a range of Brassica species, their centres of origin and distribution, reproductive biology, genetics, hybridisation and introgression, crop production, interactions with other organisms, pests and pathogens, breeding methods and biotechnological developments, and an annex on common pathogens and pests. The OECD gratefully acknowledges the contribution of Dr. R.K. Downey (Canada), the primary author, without whom this chapter could not have been written. The chapter was prepared by the OECD Working Group on the Harmonisation of Regulatory Oversight in Biotechnology, with Canada as the lead country. It updates and completes the original publication on the biology of Brassica napus issued in 1997, and was initially issued in December 2012. Data from USDA Foreign Agricultural Service and FAOSTAT have been updated. SAFETY ASSESSMENT OF TRANSGENIC ORGANISMS: OECD CONSENSUS DOCUMENTS, VOLUME 5 © OECD 2016 152 – II.3. BRASSICA CROPS (BRASSICA SPP.) Introduction The plants within the family Brassicaceae constitute one of the world’s most economically important plant groups. They range from noxious weeds to leaf and root vegetables to oilseed and condiment crops. The cole vegetables are perhaps the best known group. Indeed, the Brassica vegetables are a dietary staple in every part of the world with the possible exception of the tropics.