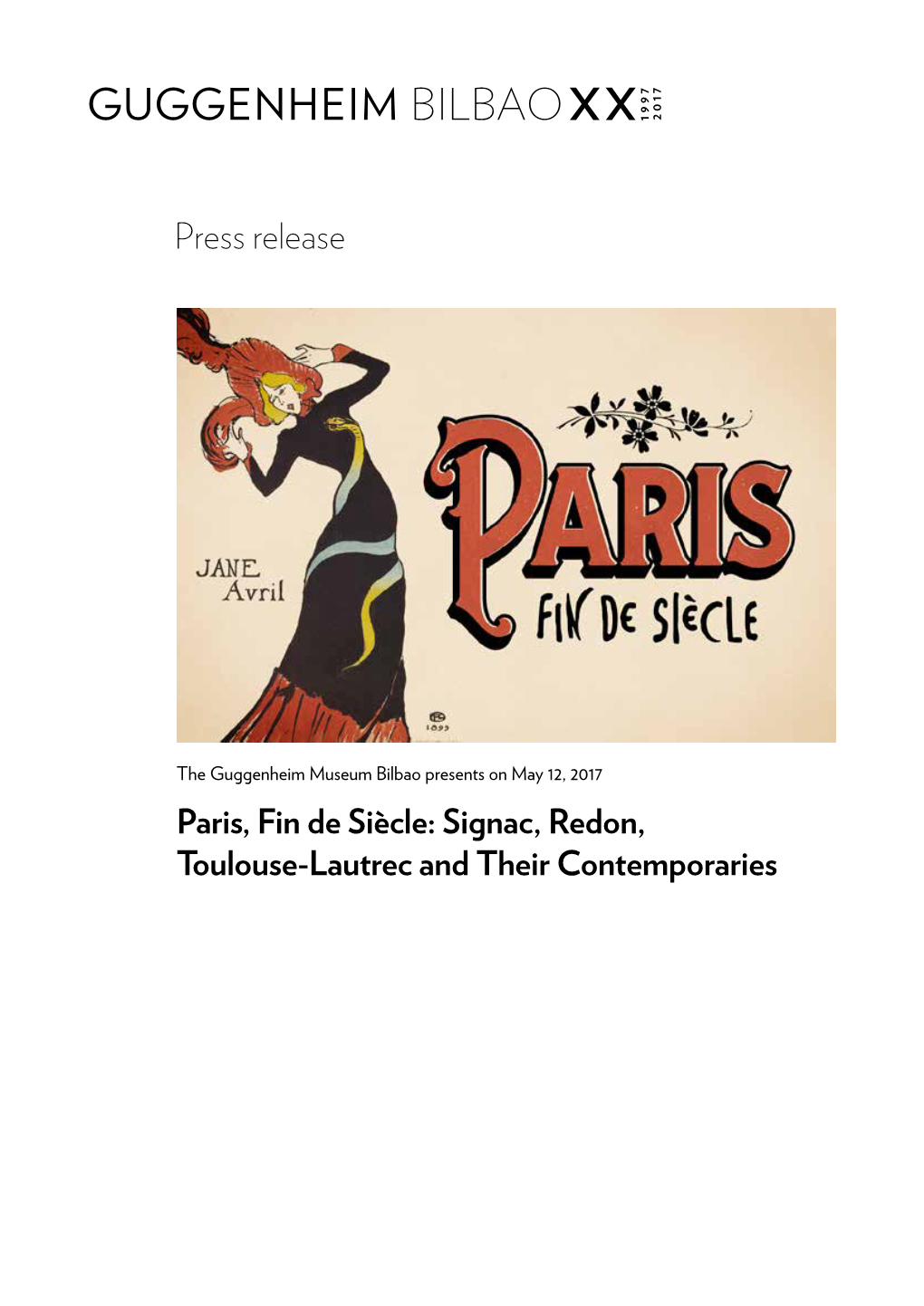

Press Release

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Artists' Journeys IMAGE NINE: Paul Gauguin. French, 1848–1903. Noa

LESSON THREE: Artists’ Journeys 19 L E S S O N S IMAGE NINE: Paul Gauguin. French, 1848–1903. IMAGE TEN: Henri Matisse. French, Noa Noa (Fragrance) from Noa Noa. 1893–94. 1869–1954. Study for “Luxe, calme et volupté.” 7 One from a series of ten woodcuts. Woodcut on 1905. Oil on canvas, 12 ⁄8 x 16" (32.7 x endgrain boxwood, printed in color with stencils. 40.6 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, 1 Composition: 14 x 8 ⁄16" (35.5 x 20.5 cm); sheet: New York. Mrs. John Hay Whitney Bequest. 1 5 15 ⁄2 x 9 ⁄8" (39.3 x 24.4 cm). Publisher: the artist, © 2005 Succession H. Matisse, Paris/Artists Paris. Printer: Louis Ray, Paris. Edition: 25–30. Rights Society (ARS), New York The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Lillie P. Bliss Collection IMAGE ELEVEN: Henri Matisse. French, 1869–1954. IMAGE TWELVE: Vasily Kandinsky. French, born Landscape at Collioure. 1905. Oil on canvas, Russia, 1866–1944. Picture with an Archer. 1909. 1 3 7 3 15 ⁄4 x 18 ⁄8" (38.8 x 46.6 cm). The Museum of Oil on canvas, 68 ⁄8 x 57 ⁄8" (175 x 144.6 cm). Modern Art, New York. Gift and Bequest of Louise The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift and Reinhardt Smith. © 2005 Succession H. Matisse, Bequest of Louise Reinhardt Smith. © 2005 Artists Paris/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP,Paris INTRODUCTION Late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century artists often took advantage of innovations in transportation by traveling to exotic or rural locations. -

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 15 (July 2015), No. 91 Claire White

H-France Review Volume 15 (2015) Page 1 H-France Review Vol. 15 (July 2015), No. 91 Claire White, Work and Leisure in Late Nineteenth-Century French Literature and Visual Culture: Time, Politics and Class. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan, 2014. 246 pp. Figures, notes, bibliography, and index. $75.00 U.S. (hb). ISBN 978-1-137-37306-9. Review by Elizabeth Emery, Montclair State University. The 2006 youth protests against the Contrat première embauche and the 2014 CGT and FO walkouts on the third Conférence sociale pour le travail provide vivid examples of the extent to which the regulation of work continues to dominate the French cultural landscape. Claire White’s Work and Leisure in Late Nineteenth-Century French Literature and Visual Culture contributes a new and fascinating, if idiosyncratic, chapter to our knowledge of French attitudes toward labor and leisure. This is not a classic history of labor reform, but rather, as the author puts it in her introduction, an attempt to situate art and literature within this well-studied context by focusing primarily on the representation of work and leisure in the novels of Emile Zola, the poetry of Jules Laforgue, and the paintings of Maximilien Luce. The book’s title should not be interpreted as a study of the representation of work and leisure in literature and visual culture in general, but in the specific case of these three artists, each of whom “engages with discourses of labour and leisure in a way which is both highly self-conscious and which reveals something about his own understanding of the processes, values and politics of cultural work in the early Third Republic” (p. -

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’S Armory Show

Recording of Marcel Duchamp’s Armory Show Lecture, 1963 [The following is the transcript of the talk Marcel Duchamp (Fig. 1A, 1B)gave on February 17th, 1963, on the occasion of the opening ceremonies of the 50th anniversary retrospective of the 1913 Armory Show (Munson-Williams-Procter Institute, Utica, NY, February 17th – March 31st; Armory of the 69th Regiment, NY, April 6th – 28th) Mr. Richard N. Miller was in attendance that day taping the Utica lecture. Its total length is 48:08. The following transcription by Taylor M. Stapleton of this previously unknown recording is published inTout-Fait for the first time.] click to enlarge Figure 1A Marcel Duchamp in Utica at the opening of “The Armory Show-50th Anniversary Exhibition, 2/17/1963″ Figure 1B Marcel Duchamp at the entrance of the th50 anniversary exhibition of the Armory Show, NY, April 1963, Photo: Michel Sanouillet Announcer: I present to you Marcel Duchamp. (Applause) Marcel Duchamp: (aside) It’s OK now, is it? Is it done? Can you hear me? Can you hear me now? Yes, I think so. I’ll have to put my glasses on. As you all know (feedback noise). My God. (laughter.)As you all know, the Armory Show was opened on February 17th, 1913, fifty years ago, to the day (Fig. 2A, 2B). As a result of this event, it is rewarding to realize that, in these last fifty years, the United States has collected, in its private collections and its museums, probably the greatest examples of modern art in the world today. It would be interesting, like in all revivals, to compare the reactions of the two different audiences, fifty years apart. -

Exhibition Checklist

Exhibition Checklist Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde—From Signac to Matisse and Beyond Musée du quai Branly-Jacques Chirac May 28, 2019-September 29, 2019 Musée de l'Orangerie October 16, 2019-January 27, 2020 The Museum of Modern Art, New York March 22, 2020-July 25, 2020 11w53, On View, 3rd Floor, South Gallery GIACOMO BALLA (Italian, 1871–1958) ALPHONSE BERTILLON (French, 1853–1914) Ravachol. François Claudius Kœnigstein. 1892 Albumen silver print 4 1/8 × 2 3/4 × 3/16" (10.5 × 7 × 0.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 ALPHONSE BERTILLON (French, 1853–1914) Fénéon. Félix. 1894–95 Albumen silver print 4 1/8 × 2 3/4 × 3/16" (10.5 × 7 × 0.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 ALPHONSE BERTILLON (French, 1853–1914) Luce. Maximilien. 1894 Albumen silver print 4 1/8 × 2 3/4 × 3/16" (10.5 × 7 × 0.5 cm) The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Gilman Collection, Museum Purchase, 2005 Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde—From Signac to Matisse and Beyond 1 ALPHONSE BERTILLON (French, 1853–1914) Police photograph of exterior of Restaurant Foyot, Paris, after the bombing on April 4, 1894 1894 Facsimile 6 × 9 1/8" (15.2 × 23.1 cm) Archives de la Préfecture de police, Paris UMBERTO BOCCIONI (Italian, 1882–1916) The Laugh 1911 Oil on canvas 43 3/8 x 57 1/4" (110.2 x 145.4 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. -

The Chester Dale Collection January 31, 2010 - January 2, 2012

Updated Monday, May 2, 2011 | 1:38:44 PM Last updated Monday, May 2, 2011 Updated Monday, May 2, 2011 | 1:38:44 PM National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 National Gallery of Art, Press Office 202.842.6353 fax: 202.789.3044 From Impressionism to Modernism: The Chester Dale Collection January 31, 2010 - January 2, 2012 Important: The images displayed on this page are for reference only and are not to be reproduced in any media. To obtain images and permissions for print or digital reproduction please provide your name, press affiliation and all other information as required(*) utilizing the order form at the end of this page. Digital images will be sent via e-mail. Please include a brief description of the kind of press coverage planned and your phone number so that we may contact you. Usage: Images are provided exclusively to the press, and only for purposes of publicity for the duration of the exhibition at the National Gallery of Art. All published images must be accompanied by the credit line provided and with copyright information, as noted. File Name: 3063-001.jpg Title Title Section Raw File Name: 3063-001.jpg Henri Matisse Henri Matisse The Plumed Hat, 1919 Display Order The Plumed Hat, 1919 oil on canvas oil on canvas Overall: 47.7 x 38.1 cm (18 3/4 x 15 in.) Title Assembly The Plumed Hat Overall: 47.7 x 38.1 cm (18 3/4 x 15 in.) framed: 65.9 x 58.1 x 5.7 cm (25 15/16 x 22 7/8 x 2 1/4 in.) Title Prefix framed: 65.9 x 58.1 x 5.7 cm (25 15/16 x 22 7/8 x 2 1/4 in.) Chester Dale Collection Chester Dale -

Download (PDF)

EDUCATOR GUIDE SCHEDULE EDUCATOR OPEN HOUSE Friday, September 28, 4–6pm | Jepson Center TABLE OF CONTENTS LECTURE Schedule 2 Thursday, September 27, 6pm TO Visiting the Museum 2 Members only | Jepson Center MONET Museum Manners 3 French Impressionism About the Exhibition 4 VISITING THE MUSEUM PLAN YOUR TRIP About the Artist 5 Schedule your guided tour three weeks Claude Monet 6–8 in advance and notify us of any changes MATISSE Jean-François Raffaëlli 9–10 or cancellations. Call Abigail Stevens, Sept. 28, 2018 – Feb. 10, 2019 School & Docent Program Coordinator, at Maximilien Luce 11–12 912.790.8827 to book a tour. Mary Cassatt 13–14 Admission is $5 each student per site, and we Camille Pissarro 15–16 allow one free teacher or adult chaperone per every 10 students. Additional adults are $5.50 Edgar Degas 17–19 per site. Connections to Telfair Museums’ Use this resource to engage students in pre- Permanent Collection 20–22 and post-lessons! We find that students get Key Terms 22 the most out of their museum experience if they know what to expect and revisit the Suggested Resources 23 material again. For information on school tours please visit https://www.telfair.org/school-tours/. MEMBERSHIP It pays to join! Visit telfair.org/membership for more information. As an educator, you are eligible for a special membership rate. For $40, an educator membership includes the following: n Unlimited free admission to Telfair Museums’ three sites for one year (Telfair Academy, Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters, Jepson Center) n Invitations to special events and lectures n Discounted rates for art classes (for all ages) and summer camps n 10 percent discount at Telfair Stores n Eligibility to join museum member groups n A one-time use guest pass 2 MUSEUM MANNERS Address museum manners before you leave school. -

Art Assignment #8

Art Assignment #8 Van Gogh Unit Van Gogh Reading/Reading Guide Due Friday, May 15, @4p Dear Art Class, Please read pages 39-61 of the van Gogh book and answer questions 79-139 of the reading guide. Please start this assignment right away. Try to pace yourself and answer at 15 questions per day. If you are part of Google Classroom turn in your google doc there. Please start a new Google Doc with questions and answers. Good luck! Hope everyone is doing well! Mr. Kohn VAN GOGH BOOK READING GUIDE QUESTIONS Pages 39-61 Vincent the Dog 1883-85 I am getting to be like a dog, I feel that the future will probably make me more ugly and rough, and I foresee that “a certain poverty” will be my fate, but, I shall be a painter. --Letter to Theo, December 1883 Vincent came home ready to give his parents another chance to do the right thing. If only his father would apologize for throwing him out of the house, they could all settle down to the important business of Vincent’s becoming an artist. Mr. van Gogh didn’t see it that way. He and Vincent’s mother welcomed their thirty-year-old problem child, but they were ambivalent at the prospect of having him back in the nest. After a few days Vincent wrote humorously yet bitterly to Theo, comparing himself to a stray dog. 39 Dear brother, I feel what Father and Mother think of me instinctively(I do not say intelligently). They feel the same dread of taking me in the house as they would about taking in a big rough dog. -

The Maria at Honfleur Harbor by George-Pierre Seurat

The Maria at Honfleur Harbor By George-Pierre Seurat Print Facts • Medium: Oil on canvas • Date: 1886 • Size: 20 ¾” X 25” • Location: National Gallery Prague • Period: • Style: Impressionism • Genre: Pointillism • Prounounced (ON-flue) • Seurat spent a summer painting six landscapes at Honfleur Harbor. They, for the most part, convey the idea of peaceful living that Seurat must have been experiencing during the summer vacation in which he created these pieces. In none of the paintings are waves crashing to shore nor is the wind forcefully blowing something. Another strange thing to note is that in none of the Honfleur paintings is there the easily recognizable shape of a human being. Maybe Seurat sees crowds of people as causes of stress and therefore never incorporates them into his Honfleur works. It is possible that this is the reason why there's an innate calmness to the six paintings. Artist Facts • Pronounced (sir-RAH) • Born December 2, 1859 • Seurat was born into a wealthy family in Paris, France. • Seurat died March 29, 1891 at the age of just 31. The cause of his death is unknown, but was possibly diphtheria. His one-year-old son died of the same disease two weeks later. • Seurat attended the École des Beaux-Arts in 1878 and 1879. • Chevreul, who developed the color wheel, taught Seurat that if you studied a color and then closed your eyes you would see the complementary color. This was due to retinal adjustment. He called this the halo effect. Thus, when Seurat painted he often used dots of complementary color. -

Edgar Degas French, 1834–1917 Woman Arranging Her Hair Ca

Edgar Degas French, 1834–1917 Woman Arranging her Hair ca. 1892, cast 1924 Bronze McNay Art Museum, Mary and Sylvan Lang Collection, 1975.61 In this bronze sculpture, Edgar Degas presents a nude woman, her body leaned forward and face obscured as she styles her hair. The composition of the figure is similar to those found in his paintings of women bathing. The artist displays a greater interest in the curves of the body and actions of the model than in capturing her personality or identity. More so than his posed representations of dancers, the nude served throughout Degas’ life as a subject for exploring new ideas and styles. French Moderns McNay labels_separate format.indd 1 2/27/2017 11:18:51 AM Fernand Léger French, 1881–1955 The Orange Vase 1946 Oil on canvas McNay Art Museum, Gift of Mary and Sylvan Lang, 1972.43 Using bold colors and strong black outlines, Fernand Léger includes in this still life an orange vase and an abstracted bowl of fruit. A leaf floats between the two, but all other elements, including the background, are abstracted beyond recognition. Léger created the painting later in his life when his interests shifted toward more figurative and simplified forms. He abandoned Cubism as well as Tubism, his iconic style that explored cylindrical forms and mechanization, though strong shapes and a similar color palette remained. French Moderns McNay labels_separate format.indd 2 2/27/2017 11:18:51 AM Pablo Picasso Spanish, 1881–1973 Reclining Woman 1932 Oil on canvas McNay Art Museum, Jeanne and Irving Mathews Collection, 2011.181 The languid and curvaceous form of a nude woman painted in soft purples and greens dominates this canvas. -

DP MD EN V4.Indd

MUSÉE CANTONAL DES BEAUX-ARTS LAUSANNE Press kit Maurice Denis. Amour 12.2 – 16.5.2021 Contents 1. Press release 2. The exhibition 3. Press images 4. Comments on 6 presented works 5. Public engagement – Public outreach services 6. Book and Giftshop – Le Nabi Café-Restaurant 7. MCBA partners and sponsors Contact Aline Guberan Florence Dizdari Communication and marketing manager Press coordinator T + 41 79 179 91 03 T + 41 79 232 40 06 [email protected] [email protected] Plateforme 10 Place de la Gare 16 T +41 21 316 34 45 Musée cantonal 1003 Lausanne [email protected] des Beaux-Arts Switzerland mcba.ch MUSÉE CANTONAL DES BEAUX-ARTS LAUSANNE 1. Press release Comrade of Édouard Vuillard and Pierre Bonnard when all three were studying art, Maurice Denis (1870-1943) was a painter and major theoretician of modern French art at the turn of the 20th century. This show – the first dedicated to the artist in Switzerland in 50 years – focuses on the early years of Denis’s career. The novel visual experiments of the “Nabi of the beautiful icons” gave way to the serene splendor of the symbolist works, followed by the bold decision to return to classicism. This event, which features nearly 90 works, is organised with the exceptional support of the Musée d'Orsay and thanks to loans from Europe and the United States. Maurice Denis remains famous for the watchword he devised in 1890, “Remember that a painting – before being a warhorse, a nude woman, or some anecdote or other – is basically a plane surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order.” Beyond this manifesto, the breadth and depth of his pictorial output make clear the ambitions of a life completely devoted to art, love, and spirituality. -

1874 – 2019 • Impressionism • Post-Impressionism • Symbolism

1874 – 2019 “Question: Why can’t art be beautiful instead of fascinating? Answer: Because the concept of beautiful is arguably more subjective for each viewer.” https://owlcation.com/humanities/20th-Century-Art-Movements-with-Timeline • Impressionism • Dada • Post-Impressionism • Surrealism • Symbolism • Abstract Expressionism • Fauvism • Pop Art • Expressionism • Superrealism • Cubism • Post-Modernism • Futurism • Impressionism is a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passage of time), ordinary subject matter • Post-Impressionism is an art movement that developed in the 1890s. It is characterized by a subjective approach to painting, as artists opted to evoke emotion rather than realism in their work • Symbolism, a loosely organized literary and artistic movement that originated with a group of French poets in the late 19th century, spread to painting and the theatre, and influenced the European and American literatures of the 20th century to varying degrees. • Fauvism is the style of les Fauves (French for "the wild beasts"), a group of early twentieth- century modern artists whose works emphasized painterly qualities and strong color over the representational or realistic values retained by Impressionism. • Expressionism is a modernist movement, initially in poetry and painting, originating in Germany at the beginning of the 20th century. ... Expressionist artists have sought to express the meaning of emotional experience rather than physical reality. • Cubism is an early-20th-century avant-garde art movement that revolutionized European painting and sculpture, and inspired related movements in music, literature and architecture.