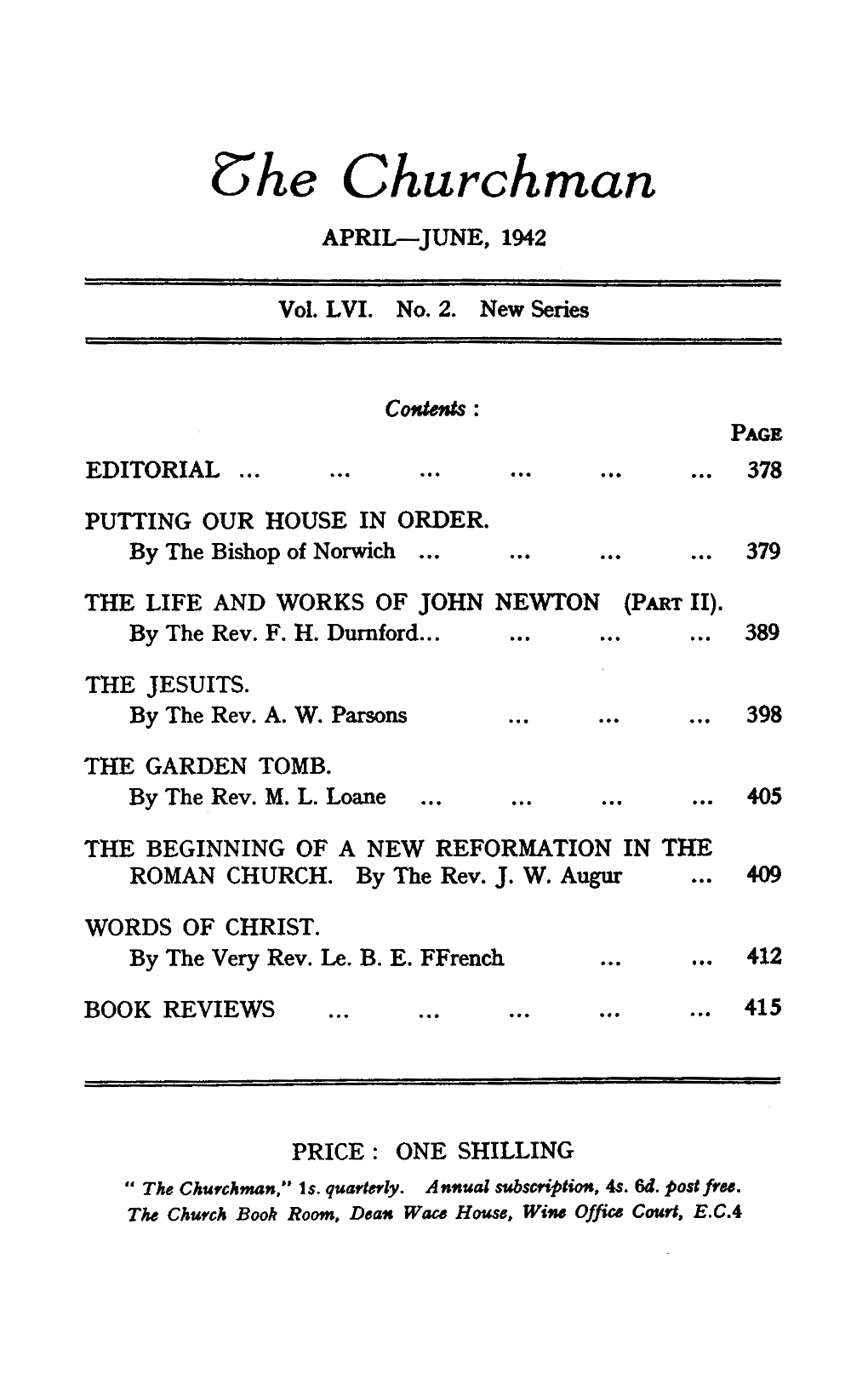

U He Churchman APRIL-JUNE, 1942

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Memorials Hilles Family

MEMORIALS of the HILLES FAMILY More particularly of SAMUEL and MARGARET HILL HILLES of Wilmington, Delaware WITH SOME ACCOUNT OF THEIR ANCESTRY AND SOME DATA NOT BEFORE PUBLISHED ALSO EXTENDED REFERENCES TO THE LIFE OF RICHARD HILLES or HILLS PRINCIPAL FOUNDER OF THE MERCHANT TAYLORS SCHOOL IN LONDON, 1561.. THE FRIEND OF MILES COVERDALE, JOHN CALVIN, ARCHBISHOP CRANMER, BISHOP HOOPER AND OTHERS, PROMINENT IN -THE EARLY DAYS OF THE REFORMATION TOGETHER WITH A HITHERTO UNPUBLISHED SONNET AND PORTRAIT OF JOHN G. \VHITTIER WITH ILLUSTRATIONS SAMUEL E. HILLES CINCINNATI 1928 Copyright, 1928, by SAMUEL E. HILLES Printed in the United States of America Frontispiece SAMUEL HILLES 1788-1873 Photographed about 1870. To the cherished memory of SAMUEL HILLES and MARGARET HILL HILLES this labor of love is affectionately dedicated by their grandson "In March, 1638, the first group of colonists sent out by the Government of Sweden was landed at 'The Rocks,' a natural wharf at Christiana Creek, just above its junction with the Brandywine. The transport was an armed vessel named from an important port of the southern coast of Sweden, 'Key of Kalmar.' The photographic reproduction herewith was made from the miniature model in the Swedish Naval Museum. The ship was of less than two hundred tons burden, and the cargo consisted of adzes, knives and other tools, mirrors, gilt chains and the like, for trade with the natives. The leader of the expedition, Peter Minuit, was a native of Holland." -Courtesy of Wilmington Trust Company. FOREWORD HESE MEMORIALS, in mind for many years, have finally been undertaken, as a labor of love, by a grandson who was T named for the grandfather and closely associated with the later life of SAMUEL HILLES and MARGARET HILL HILLES, in their home in Wilmington, Delaware. -

Founder and First Organising Secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893-1952, N.D

British Library: Western Manuscripts MANSBRIDGE PAPERS Correspondence and papers of Albert Mansbridge (b.1876, d.1952), founder and first organising secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893-1952, n.d. Partly copies. Partly... (1893-1952) (Add MS 65195-65368) Table of Contents MANSBRIDGE PAPERS Correspondence and papers of Albert Mansbridge (b.1876, d.1952), founder and first organising secretary of the Workers' Educational Association; 1893–1952, n.d. Partly copies. Partly... (1893–1952) Key Details........................................................................................................................................ 1 Provenance........................................................................................................................................ 1 Add MS 65195–65251 A. PAPERS OF INSTITUTIONS, ORGANISATIONS AND COMMITTEES. ([1903–196 2 Add MS 65252–65263 B. SPECIAL CORRESPONDENCE. 65252–65263. MANSBRIDGE PAPERS. Vols. LVIII–LXIX. Letters from (mostly prominent)........................................................................................ 33 Add MS 65264–65287 C. GENERAL CORRESPONDENCE. 65264–65287. MANSBRIDGE PAPERS. Vols. LXX–XCIII. General correspondence; 1894–1952,................................................................................. 56 Add MS 65288–65303 D. FAMILY PAPERS. ([1902–1955]).................................................................... 65 Add MS 65304–65362 E. SCRAPBOOKS, NOTEBOOKS AND COLLECTIONS RELATING TO PUBLICATIONS AND LECTURES, ETC. ([1894–1955])......................................................................................................... -

UNIVERSITY of LONDON INSTITUTE Jf EDUCATION

UNIVERSITY OF LONDON INSTITUTE j f EDUCATION LIBRARY NOT TO BE REMOVED FROM LiBRART RELIGIOUS EDUCATION AND ITS UNDERLYING STRUCTURE. Andrew Sangster M.Phil Institute of Education, University of London. 1 X - / < I -Sol^S7 - 0 ABSTRACT Part 1 of this thesis is an historical survey of the legislation and development of Religious Education as a school subject. Part 2 is a study of the different approaches to the subject. The thesis outlines a continuing tension within the subject between those who see Religious Education as a phenomenological study; those who see it as a confessional opportunity; and those who view it as a broad discussion period or nurturing experience. There is also an examination of the issues relating to Moral Education within this subject. Part 3 summarises the historical perspective, examines the nature of the subject in the light of educational theory, makes a brief examination of the 1992 White Paper (Choice and Diversity) and finally sets out the idea that if the right approaches to the subject are adopted there is no need for the opting-out clauses in the Government legislation. 2 CONTENTS GENERAL INTRODUCTION p.4 PART I CHAPTER 1. A Brief History to 1944 p.8 CHAPTER 2. The 1944 Education Act p.25 CHAPTER 3. 1945-1959 p.43 CHAPTER 4. The 1960s p.56 CHAPTER 5. 1970-88 p.92 PART 2 INTRODUCTION TO PART 2 P.121 CHAPTER 6. Confessionalisra p.122 CHAPTER 7. The Moral Perspective p.139 CHAPTER 8. The Implicit Approach p.157 CHAPTER 9. The Explicit Approach p.171 PART 3 INTRODUCTION TO PART 3 P.186 CHAPTER 10. -

Synod of the Missionary Diocese of Algoma

A.D. 1950 Journal of Proceedings OF THE SIXTEENTH SESSION OF THE Synod of the Missionary Diocese of Algoma CLIFFE PRINTING COMPANY SAULT STE . MARIE, ONTARIO {J;tutral ~yunb of tbe arl1urtl1 nf fnglnnb in arnnnbn mnrnutn Attessinu Numher.· .. ·· ... .· . .· . ......... ...... ....... ... .. ... .. .. .......... .. ... THE INCORPORATED SYNOD OF THE Missionary Diocese of Algoma OF THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND IN CANADA Journal of Proceedings OF THE SIXTEENTH SESSION Held in the City of Sault Ste. l\'Iarie, Ontario, from June 6th to 8th in-elusive A.D. 1950. WITH ApPENDICES t:l:LERGY AND' OFFlcERS; DIOCESE <JF ALG'OMA.· ''l!he' Bisltop;' The Right Rev. William Lockridge" Wright" D'.D';, Bishophur'st, Sault 'Site. Marie';' O,n,t. The :Dean~ , TIre Very Irev. J. H. Oraigr' M.k) }) .]) ~ , Al1cbdeaeonS" , ___ ___ . __ _ tIle Veri:'. C. VV .. Balf&ur, M.A., Archdeacon emeritusf saurt See. Marie' The Ven-. J. B. Lilrdsell, Archdeacon of Muskoka ____ .. .. _,'___ _, . ____ _____,. Gravenhurst The' Vel'],. J. S ... Smedley'f L .'llh'1 Archdeacon~ of Algoma: _____ ..__ ~< __ _ Po.rt Arthm:-' HonO'rary CaU:ons: The Rev. F: W . ColIotoI1, E .A.,- B.D. __ ________________ _, ..__ __ _._ __ __ . __ ____ ~. __ S''3!ul't Ste: Marie' The' Rev. C. C. Simpson;, L.Th. (Retired) __ __ ______ __ __ _,_. __ __ __ ,____ ___ _____________ Orangeville The Rev. RIchard Haines _______________________________ __ .__ ., .... ___________ ____ ____________ Little Current The ReV'. H. A. Bilns ____ __ ___ _,_ _, ___ __ __. _'____ _______ _.__ ,_____ _-.' _ ___ __ '______ ___ ,_,'___ __ '. -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses The church colleges 1890-1944,with special reference to the church of England colleges and the role of the national society Boyd, Michael V. How to cite: Boyd, Michael V. (1981) The church colleges 1890-1944,with special reference to the church of England colleges and the role of the national society, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/7517/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 THE CHURCH COLLEGES 1890-1946, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND COLLEGES AND THE ROLE OF THE NATIONAL SOCIETY A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Durham School of Education by MICHAEL V. BOYD 1981 ABSTRACT THE CHURCH COLLEGES 1890-1944, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND COLLEGES AND THE ROLE OF THE NATIONAL SOCIETY Michael V. -

Book Reviews PRAISE of GLORY

82 THE CHURCHMAN that are offered. But I take a mental note of them all, endeavouring to weave any which may be helpful into the general structure of the service, and thus church worship becomes more and more the vital energetic channel of the grace of God, and worshippers learn the truth of the old dictum-" Man's chief end is to glorify God, and to enjoy Him for ever." Book Reviews PRAISE OF GLORY. By E. I. Watkin. iv and 280 pp. Skeed and Ward, 1943, 10/6. This commentary of thirteen chapters on Lauds and Vespers is by a Roman Catholic Ia·yman, who was received into the Roman Church at Downside at the age of twenty years. Mr. Watkin is knovm for his philosophical and theological writings and for his translation of Halevy's History of the English People " and Maritafn's" Introduction to Philosophy." The Catholic News-Letter has pointed out that "Jay scholars have exerted a very powerful influence upon the development of the Breviary," and it is there fore fitting that a layman should write a commentary showing such a keen understanding and appreciation of the Hours of the I{oman Breviary. The Roman Church is fortunate in having a layman so well-informed and so well versed in liturgiology that he is able to supply a running commentary on the Psalms and other parts of the two Offices, skilfully explaining the intricacies of the Common and Proper of Saints, proposing thoughts which will be helpful in interpreting the chief themes and in following the leitmotif of the days, and at the same time injecting little personal notes which considerably add to the interest of the book. -

Goddard Society Lunch 10Th September 2016 I: Spencer Leeson Spencer Leeson, Headmaster from 1934 to 1946, Was, of Course, a Gian

Goddard Society Lunch 10th September 2016 I: Spencer Leeson Spencer Leeson, Headmaster from 1934 to 1946, was, of course, a giant. He was Chairman of HMC seven times, and was to become Bishop of Peterborough. Leeson was immensely proud of Winchester College. Few things, even the Nazis, perturbed him. So when an anxious colleague asked him in 1939 what would happen when the Germans landed, Leeson responded that it would be time to think about that when the invaders got to Eastleigh. It is possible that there was only one thing that perturbed the formidable Spencer Leeson. John Dancy, in his biography of Walter Oakeshott, gives us a clue. He tells us that a bright young thing once asked Leeson “and how do you like being Headmaster of Winchester, Mr Leeson?” “Madam”, was the grave reply, “how will you like the Day of Judgement?”. II: The 59th Headmaster So how do I like the day of judgement? My wife tells me that for the first time in many a year, I am singing as I walk around our house. She is therefore, for her own part, very unhappy, as you may imagine, about our move. She last night reminded me that, after we were both privileged to be asked down here in June last year to discuss the headmastership with the Warden and Fellows, we went, once proceedings had ended, to Winchester Cathedral, and sat together there, in silence, in the nave. We paid our respects to William of Wykeham, and also to William Waynflete, one of my predecessors as Headmaster here, and Founder of my previous school, Magdalen College School. -

(Edward Fitz-) Gerald Brenan Carlos Pranger (Estelle) Sylvia Pankhurst

Name(s) for which Copyright is Contact name Organisation held (Alastair) Brian (Clarke) Harrison Susanna Harrison (Edward Fitz-) Gerald Brenan Carlos Pranger (Estelle) Sylvia Pankhurst & Dame Christabel Pankhurst, New Times & Ethiopia News Professor Richard Pankhurst (George) Geoffrey Dawson Robert Bell Langliffe Hall (Henry) David Cunynghame & Sir Andrew Cunynghame Sir Andrew Cunynghame (Henry) David Cunynghame, Shepperton Film Studios Magdalena Dulce Shepperton Studios Ltd (Herbert) Jonathan Cape, George Wren Howard & Jonathan Cape Ltd (Publishers) Jo Watt Random House (Isabelle) Hope Muntz Valerie Anand (Joint) International Committee of Movements for E, Dr Joseph H Retinger, European Movement, European Movement, Paris, International Committee of Movements for European, International Council of European Movement, Paul-Henri Spaak, Rachel Ford, Sir Harold Beresford Butler, Thomas Martin & United Kingdom Council of European Movement Joao Diogo Pinto European Movement (Nicholas) Robin Udal John Oliver Udal (Reginald) Jack Daniel Reginald Jack Daniel (Sydney) Ivon Hitchens John Hitchens (Thomas) Malcolm Muggeridge, Alan (John Percival) Taylor, Dorothy Leigh Sayers, Robert Howard Spring G Glover David Higham Associates Ltd (William Ewart) Gladstone Murray, Alfred Ryan, Antony Craxton, Baron of Lonsdale Sir William Jocelyn Ian Fraser, BBC, BBC Empire Executive, Cyril Conner, John Beresford Clark, Lt- Gen Sir (Edward) Ian (Claud) Jacob, Peter (Robert) Fleming, Rt Hon John (Henry) Whitley, Rt Hon Sir Alexander George Montagu Cadogan, Sir William -

195463077.23.Pdf

7A L. Uo1^ FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY. U Th is Book is the property of H.B.M. Government and is to be kept in safe custody by the person to whom it has been Issued. Hu Jhifftoritu SUPPLEMENT TO THE MONTHLY ARMY LIST. AUGUST, 1915. PROMOTIONS, APPOINTMENTS, ETC., GAZETTED, AND DEATHS OF OFFICERS R€PORTED, BETWEEN 1st & 31st JULY, 1915. LISTS OF SOLDIERS’ BALANCES UNCLAIMED. LONDON: PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE, BY J. J. KELIHER k CO., LTD., MABSHALSEA ROAD, S.E. FOR OFFICIAL USE ONLY This Book is the property of H.B.M. Government, and is to be kept in sate custody by the person to whom it has been issued. [ Crown Copyright Reserved^ 3Bn Autljaritn. SUPPLEMENT TO THE MONTHLY ARMY LIST. AUGUST, 1910. PROMOTIONS, APPOINTMENTS, ETC., GAZETTED, AND DEATHS OF OFFICERS REPORTED, BETWEEN 1st & 31st JULY, 1915. LISTS OF SOLDIERS’ BALANCES UNCLAIMED. LONDON: PRINTED UNDER THE AUTHORITY OF HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE, BY J. J. KELIHER & CO., LTD.. MARSHALSEA ROAD, S.E. 92468—Wt. 20143—11,500—8/16—J. J. K. & Co. Ltd. 1 Promotions, Appointments, &c. S 3C PROMOTIONS, APPOINTMENTS, &c., since last Publication. War Office., 31st July, 1915. REGULAR FORCES. ARMY. {Extract from the London Gazette, ‘Pith July, 1915.) War Office, With July, 1915. His Majesty The KING has been graciously pleased to promote Major (temporary Lieutenant-Colonel) A. W. P. Knox, 68th Vaughan’s Rifles (!■ rentier Force), Indian Army, to i revet Lieutenant-Colonel in recognition of his distinguished service. Dated 14 July, 1»15. ****** COMMANDS & STAFF. -

The English Journals of Religious Education and the Movement For

[To cite this article: Parker S. G., Freathy, R. and Doney, J. (2016). The Professionalisation of Non-Denominational Religious Education in England: politics, organisation and knowledge. Journal of Beliefs and Values, 37(2).] The Professionalisation of Non-Denominational Religious Education in England: politics, organisation and knowledge Stephen G. Parker,*1 Rob Freathy,** and Jonathan Doney** * Institute of Education, University of Worcester and **Graduate School of Education, University of Exeter Abstract In response to contemporary concerns, and using neglected primary sources, this article explores the professionalisation of teachers of Religious Education (RI/RE) in non- denominational, state-maintained schools in England. It does so from the launch of Religion in Education (1934) and the Institute for Christian Education at Home and Abroad (1935) to the founding of the Religious Education Council of England and Wales (1973) and the British Journal of Religious Education (1978). Professionalisation is defined as a collective historical process in terms of three inter-related concepts: (1) professional self-organisation and professional politics, (2) professional knowledge, and (3) initial and continuing professional development. The article sketches the history of non-denominational religious education prior to the focus period, to contextualise the emergence of the professionalising processes under scrutiny. Professional self-organisation and professional politics are explored by reconstructing the origins and history of the Institute of Christian Education at Home and Abroad, which became the principal body offering professional development provision for RI/RE teachers for some fifty years. Professional knowledge is discussed in relation to the content of Religion in Education which was oriented around Christian Idealism and interdenominational networking. -

OCA Newsletter 2017

Peterborough Cathedral Old Choristers’ Association 2017 Newsletter PETERBOROUGH CATHEDRAL OLD CHORISTERS’ ASSOCIATION 2017 NEWSLETTER 2017 REUNION This year’s reunion took place on Saturday 16 September. Once again, it was held in conjunction with the annual gathering of the Friends of the Cathedral. Old choristers assembled in the stalls and rehearsed with the choirs under the genial direction of Steven Grahl. Before the service, DAVID LOWE laid a wreath at the memorials in St. Sprite’s Chapel in memory of old choristers and former pupils of The King’s School who gave their lives in the two world wars. The first lesson at Evensong was read by SUZ FRANKS. After the service, the Annual General Meeting was held in the Almoner’s Hall. The final event of the day was the reunion dinner, which was held at The Park Inn. Speakers were Canon Ian Black and old chorister CHRISTOPHER BROWN. A first-class meal was enjoyed by the assembled company. The reunion proved, as always, to be a very happy and delightfully nostalgic event. NEW OFFICERS At the AGM, TIM HURST-BROWN was elected as Chairman of the Association. SIMON WILKINSON stood down as Hon. Secretary after being in office for eleven years. He was thanked warmly for his work and particularly for his skilful and unobtrusive organisation of the annual dinners. His successor is LOUISE LAPRUN, to whom we wish every success in this demanding role. She has a hard act to follow, but with the support of the committee and all our members she is sure to make a great success of her new post.