Rushing Union Elections: Protecting the Interests of Big Labor at the Expense of Workers’ Free Choice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Why a Union Voice Makes a Real Difference for Women Workers: Then and Now

Why a Union Voice Makes a Real Difference for Women Workers: Then and Now Judith A. Scottt ABSTRACT: Working women, labor unions, and collective action played a crucial role in passing and implementing the Pregnancy Discrimination Act. The Article describes how labor unions pushed for the passage of the Act and later made protections for pregnant workers real through collective bargaining, internal education efforts, and litigation. Finally, the Article discusses the fundamental improvements for working women that still must be achieved- and the need for strengthened worker organizations if those changes are to become a reality. IN TRO DU CTION ................................................................................................ 233 I. THE FIRST STEP: THE ROLE OF UNIONS IN PASSING THE PDA ................... 234 II. UNION ADVOCACY: MAKING THE PDA REAL FOR WORKERS ................... 235 III. BEYOND THE PDA: THE FUTURE ROLE OF UNIONS IN SECURING THE RIGHTS OF W OMEN W ORKERS ............................................................. 241 C ON CLU SION ................................................................................................... 244 INTRODUCTION In this Article, I describe an important story behind the passage and implementation of the 1978 Pregnancy Discrimination Act (PDA)I--one that has continuing implications for creating a society that delivers for poor and working families and rebuilds the middle class. It is the story of how the empowerment of working women and collective action were crucial to improving workplace culture and practices for pregnant workers thirty years ago, and why those same factors are necessary today if we are to dramatically t Judith A. Scott is currently General Counsel of the Service Employees International Union and a member of the law firm of James & Hoffman, P.C., Washington, D.C. -

How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers' Rights

How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights ICED OUT: How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights ICED OUT | How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights by Rebecca Smith, National Employment Law Project; Ana Avendaño, AFL-CIO; Julie Martínez Ortega, American Rights at Work Education Fund Photo Credits: Photos featured in this report were generously supplied by the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice. © October 2009. All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements: Eddie Acosta, AFL-CIO; Erin Johansson, American Rights at Work Education Fund; Michael L. Snider, Attorney at Law; Jenny Yang, Cohen, Milstein, Sellers and Toll; Brooke Anderson, East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy; Brooke Greco, Florida Immigrant Advocacy Center; Brady Bratcher, Iron Workers Union Local 75; Hillary Ronen, La Raza Centro Legal; Renee Saucedo, La Raza Centro Legal; Jennifer Rosenbaum, New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice; Julie Samples, Oregon Law Center ; Jacqueline Ramirez, Service Employees International Union Local 87; Siovhan Sheridan-Ayala, Sheridan Ayala Law Office; Mary Bauer, Kristin Graunke, Monica Ramirez and Andrew Turner, Southern Poverty Law Center; Vanessa Spinazola, The Pro Bono Project; Gening Liao, formerly of United Food and Commercial Workers; Randy Rigsby, United Steelworkers District 9; Jim Knoepp, Virginia Justice Center. 2 ICED OUT: How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction ......................................................................... 5 II. Immigration and Labor Law in Context ................................................ 7 III. Federal Policies Fail to Ensure Appropriate Balance Between Immigration and Labor Law Enforcement ................................... 13 IV. Case Studies: Immigration Enforcement Trumps Labor Rights .........................15 V. The Need to Identify and Assist Workers Who Are Victims of Labor Trafficking Rather than Focusing on Their Deportation ................30 VI. -

"We Are the Kickers!" the Milwaukee

WE ARE THE KICKERS! The Milwaukee Kickers Story Chapter 1: “Realizing a Dream” The Wisconsin Soccer Association began a youth soccer program in 1962 with the Milwaukee County Parks & Recreation Department, which, by 1968, had become the third largest participation sport in the park system. In 1970, it moved up to second largest. Because the league program was basically ethnic-oriented, it became evident in 1968 to several people deeply involved in Milwaukee area soccer clubs that a new club needed to be formed to accommodate the growing number of American kids enjoying the game. Recognizing the lack of opportunity for the American player in an almost totally ethnic controlled sport, the 12 initiators wanted to develop the sport in a unique way to become a “traditional American” sport: to give everyone a place and a chance to play, boys and girls alike; to provide good coaching and stable administration; and, most importantly, to develop FAMILY INVOLVEMENT, which, in turn, would provide a strong volunteer base from which to operate the club. After much soul searching, these people left their respective clubs and founded the Milwaukee Kickers in November, 1968. Using the slogan, “American Soccer is Our Goal”, and choosing red and gray as club colors, the twelve Founders were: Carol and Lorenzo Draghicchio, Lew and Louise Dray, Dorothy and Frank Kral, Aleks and Helga Nikolic, Irene and Milan Nikolic, Elfriede and Sirous Samy . The fledgling club operated literally on a shoestring, relying almost entirely on car washes, rummage sales, newspaper drives and merchandise sales to finance the operation. The first adult squads competed in January, 1969, in the Indoor Season of the WSA at the Milwaukee Auditorium. -

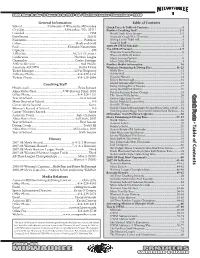

2008-09 Media Guide

UUWMWM Men:Men: BBrokeroke 1010 RecordsRecords iinn 22007-08007-08 / HHorizonorizon LeagueLeague ChampionsChampions • 20002000 1 General Information Table of Contents School ..................................University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Quick Facts & Table of Contents ............................................1 City/Zip ......................................................Milwaukee, Wis. 53211 Panther Coaching Staff ........................................................2-5 Founded ...................................................................................... 1885 Head Coach Erica Janssen ........................................................2-3 Enrollment ............................................................................... 28,042 Assistant Coach Kyle Clements ..................................................4 Nickname ............................................................................. Panthers Diving Coach Todd Hill ................................................................4 Colors ....................................................................... Black and Gold Support Staff ...................................................................................5 Pool .................................................................Klotsche Natatorium 2008-09 UWM Schedule ..........................................................5 Capacity..........................................................................................400 Th e 2008-09 Season ..............................................................6-9 -

How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers' Rights

How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights ICED OUT: How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights ICED OUT | How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights by Rebecca Smith, National Employment Law Project; Ana Avendaño, AFL-CIO; Julie Martínez Ortega, American Rights at Work Education Fund Photo Credits: Photos featured in this report were generously supplied by the New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice. © October 2009. All Rights Reserved. Acknowledgements: Eddie Acosta, AFL-CIO; Erin Johansson, American Rights at Work Education Fund; Michael L. Snider, Attorney at Law; Jenny Yang, Cohen, Milstein, Sellers and Toll; Brooke Anderson, East Bay Alliance for a Sustainable Economy; Brooke Greco, Florida Immigrant Advocacy Center; Brady Bratcher, Iron Workers Union Local 75; Hillary Ronen, La Raza Centro Legal; Renee Saucedo, La Raza Centro Legal; Jennifer Rosenbaum, New Orleans Workers’ Center for Racial Justice; Julie Samples, Oregon Law Center ; Jacqueline Ramirez, Service Employees International Union Local 87; Siovhan Sheridan-Ayala, Sheridan Ayala Law Office; Mary Bauer, Kristin Graunke, Monica Ramirez and Andrew Turner, Southern Poverty Law Center; Vanessa Spinazola, The Pro Bono Project; Gening Liao, formerly of United Food and Commercial Workers; Randy Rigsby, United Steelworkers District 9; Jim Knoepp, Virginia Justice Center. 2 ICED OUT: How Immigration Enforcement Has Interfered with Workers’ Rights TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .. ........................ 5 II. Immigration and Labor Law in Context . 7 III. Federal Policies Fail to Ensure Appropriate Balance Between Immigration and Labor Law Enforcement . 13 IV. Case Studies: Immigration Enforcement Trumps Labor Rights . 15 V. The Need to Identify and Assist Workers Who Are Victims of Labor Trafficking Rather than Focusing on Their Deportation . -

The Case Against the So-Called Right to Work Act, 15 La

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Louisiana State University: DigitalCommons @ LSU Law Center Louisiana Law Review Volume 15 | Number 1 Survey of 1954 Louisiana Legislation December 1954 The aC se Against the So-Called Right to Work Act William J. Dodd Repository Citation William J. Dodd, The Case Against the So-Called Right to Work Act, 15 La. L. Rev. (1954) Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.lsu.edu/lalrev/vol15/iss1/18 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at LSU Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Louisiana Law Review by an authorized editor of LSU Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Case Against the So-Called Right to Work Act William J. Dodd* Act 252 of 1954, referred to as "Louisiana's Right to Work Law," was without question the most controversial legislative problem considered during the 1954 legislative session. The act is class legislation and may well result in a disruption of the otherwise harmonious labor relations that have existed in Lou- isiana up to the present time. Without attempting to go into the reasons why the sponsors and backers of this legislation promoted its passage, let us look at the harm the enforcement of this act can bring to labor relations in Louisiana. Briefly, the following indictments can be brought against this so-called "Right to Work" act:' It will disrupt the harmonious relations presently existing between labor and management and unreasonably restrict em- ployees in the exercise of freedom of speech and communication by forbidding picketing or other lawful means of communi- cating the facts regarding labor disputes. -

The Case for a Fair Deal Labor Policy, Speeches in Senate, Washington, D.C., June 10 and 14, 1949

Th_e Case for a Fair Deal Labor Policy Speeches of HON. HUBERT H. HUMPHREY of Minnesota In the Senate of the United States l June 10 and 14, 1949 "I submit that the processes of democracy are a s relentless and ever-flowing as the )ide itself ..• the American people, the worlcing people of this country, the people who have been oppressed by this law-, are determined that they are going to remove this kind of punitive legislation from the statute books, and are determine.d that they are going to have something to say about the proc esses of government, because this country is their r-- country, as well as it is yours and mine." NOT PRINTED AT GOVERNM~NT EXPENSE 844385---30518 <tongrrssional Rrcord PROCEEDINGS AND DilBATES OF THE 81st CONGRESS, FIRST SESSION A Case For a Fair .Labor Policy SPEECHES of the appropriate purposes· of such pol OF icy. What can_a Government labor pol icy achieve and what are its limits? Table of Contents HON. -HUBERT H. HUMPHREY What should a Government try to do in OF MINNESOTA that field, and what should it refrain IN THE SENATE OF THE UNITED STATES from trying to do? Page June 10 and 14, 1949 Statements of objectives too often are Objectives of a. National L abor Policy____________ 3 mere generalizations on which everyone The P lace of Labor Unions in Our Economy______ 8 can agree. This is true of much of the June 10, 1949 "declaration of policy" in the preamble H istorical Background of Government's Attitude The Senate resumed the consideration of. -

BRINGING the WORKERS' RIGHTS BACK IN? the Discourses And

Simon Pahle Philosophiae Doctor (P Department of International EnvironmentNorwegian and Development University Studies, of Life SciencesNoragric • Universitetet for miljø- og biovitenskap ISBN 978-82-575-0980-4 ISSN 1503-1667 BRINGING THE WORKERS’ RIGHTS BACK IN? The Discourses and Politics of fortifying h D) Thesis 2011:16 Core Labour Standards through a Labour- Trade Linkage Simon Pahle Philosophiae Doctor (P h D) Thesis 2011:16 Norwegian University of Life Sciences NO–1432 Ås, Norway Phone +47 64 96 50 00 www.umb.no, e-mail: [email protected] BRINGING THE WORKERS’ RIGHTS BACK IN? The Discourses and Politics of fortifying Core Labour Standards through a Labour-Trade Linkage Philosophiae Doctor (PhD) Thesis Simon Pahle Department of International Environment and Development Studies (Noragric) Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB) Ås 2011 Thesis number 2011:16 ISBN 978-82-575-0980-4 ISSN 1503-1667 TIL MATHIAS & GABRIEL (Alt har sin pris) BRINGING THE WORKERS’ RIGHTS BACK IN? The Discourses and Politics of fortifying Core Labour Standards through a Labour-Trade Linkage ABSTRACT Throughout the 1990s the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) conducted a campaign to convince states to institute a linkage between the international labour and trade regimes (also dubbed a social clause): Trading rights granted to countries qua members of the World Trade Organisation (WTO) would be made conditional on their compliance with International Labour Organisation (ILO) core labour standards – i.e., their upholding of the rights that enable workers ‘to claim a fair share of the wealth they have helped to generate’. The proposal was premised on the claim that increasing global competition confers commercial advantages on producers that undercut labour standards, and that this incites a regulatory race to the bottom. -

About the Wisconsin Policy Forum

About the Wisconsin Policy Forum The Wisconsin Policy Forum was created on January 1, 2018, by the merger of the Milwaukee-based Public Policy Forum and the Madison-based Wisconsin Taxpayers Alliance. Throughout their lengthy histories, both organizations engaged in nonpartisan, independent research and civic education on fiscal and policy issues affecting state and local governments and school districts in Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Policy Forum is committed to those same activities and to that spirit of nonpartisanship. Preface and Acknowledgments This report was undertaken to paint a clearer picture of the youth sports landscape in the city of Milwaukee: what options are available to kids and their families, what are the characteristics of these programs and how are they supported financially, and what are some of the primary challenges facing the city’s youth sports organizations. We hope that this research will help guide youth sports leaders, funders, and policymakers. Report authors would like to thank the representatives of youth sports organizations who shared information by responding to our survey, as well as key informants who provided additional insight. In addition, we are grateful to members of the advisory committee convened to guide this report for generously providing their time and expertise; and to representatives from Milwaukee Recreation for taking the time to provide us with important information about the unique role they play in Milwaukee’s youth sports landscape. Finally, we wish to thank the Milwaukee Youth Sports Alliance for spearheading this initiative, and the Milwaukee Bucks and Bader Philanthropies for their contributions that helped make this research possible. -

Tmobilereport Layout 1.Qxd

LOWERING THE BAR OR SETTING THE STANDARD? DEUTSCHE TELEKOM’S U.S. LABOR PRACTICES www.americanrightsatwork.org Lowering the Bar or Setting the Standard? Deutsche Telekom’s U.S. Labor Practices By John Logan, Ph.D., Director of Labor Studies, San Francisco State University © December 2009 American Rights at Work Education Fund All photos courtesy Communications Workers of America LOWERING THE BAR OR SETTING THE STANDARD? DEUTSCHE TELEKOM’S U.S. LABOR PRACTICES By John Logan, Ph.D. Director of Labor Studies, San Francisco State University 2 Preface 11 T-Mobile’s Intensive Union Avoidance Campaign 3 Introduction: Deutsche Telekom’s Corporate 16 The NLRB Exposes T-Mobile USA’s Anti-Union Double Standard Inspires a New Global Intimidation Partnership for Workers 19 Why Workers Want and Need a Voice 5 T-Mobile USA and the American System of Labor Relations 27 Conclusion 8 Conflict Versus Cooperation: Deutsche Telekom in the United States PREFACE During my years of service in the U.S. House of Representatives, I saw the remarkable drive and promise of American businesses and workers. Along with my House colleagues, I championed the view that a level playing field is fundamental in crafting public policy solutions that both advance the interests of America’s workers and help our business sector responsibly engage in the global economy. The important research documented in this report highlights some of the key questions we face as a nation in a competitive 21st century economy. Do we reward those who play by the rules, or those who skirt the rules for their own gain? Do we encourage partnerships that bring workers’ voices to the table and protect their rights, or allow companies to violate the letter and the spirit of our labor laws in pursuit of short-term gain? In 2000, my colleagues on the House Subcommittee on Telecommunications, Trade and Consumer Protec- tion heard testimony in support of the German telecommunications company Deutsche Telekom’s pro- posed acquisition of VoiceStream Communications. -

Govind Swarup: Radio Astronomer, Innovator Par Excellence and a Wonderfully Inspiring Leader

LIVING LEGENDS IN INDIAN SCIENCE Govind Swarup: Radio astronomer, innovator par excellence and a wonderfully inspiring leader G. Srinivasan They are ill discoverers that think there the important contributions to cosmology is no land, when they can see nothing but being made using this telescope. He sea. mentioned in very flattering terms the Francis Bacon Ph D thesis of one of Swarup’s students (Vijay Kapahi) which had come to him I must say at the outset that I have no for evaluation. That is how I came to special credentials to write an article know of Swarup. about as famous a person as Govind As it turned out, I moved from Cam- Swarup. I am not one of his numerous bridge to the Raman Research Institute students. Nor have I collaborated with (RRI), Bangalore in the beginning of him in research. Indeed, I am not even an 1976. Within weeks after my coming, I astronomer, let alone a radio astronomer. received an invitation from Govind Swa- But I have been one of his great admir- rup to attend a small meeting he had ers, and he has been a beacon of inspira- convened at RRI to discuss a Summer tion for me during the past four decades. School in Astronomy he was organizing I was therefore delighted – although sur- in Bangalore in June 1976. I was rather prised – when the Editor of Current Sci- surprised because I was still working in ence invited me to write this article. The Condensed Matter Physics. There were K. S. Krishnan, B. N. -

Renewing and Maintaining Union Vitality: New Approaches to Union Growth

NYLS Law Review Vols. 22-63 (1976-2019) Volume 50 Issue 2 Next Wave Organizing Symposium Article 3 January 2006 Renewing and Maintaining Union Vitality: New Approaches to Union Growth Fred Feinstein University of Maryland's School of Public Policy Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.nyls.edu/nyls_law_review Part of the Business Organizations Law Commons, Labor and Employment Law Commons, Law and Economics Commons, and the Organizations Law Commons Recommended Citation Fred Feinstein, Renewing and Maintaining Union Vitality: New Approaches to Union Growth, 50 N.Y.L. SCH. L. REV. (2005-2006). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@NYLS. It has been accepted for inclusion in NYLS Law Review by an authorized editor of DigitalCommons@NYLS. \\server05\productn\N\NLR\50-2\NLR209.txt unknown Seq: 1 14-APR-06 7:51 RENEWING AND MAINTAINING UNION VITALITY: NEW APPROACHES TO UNION GROWTH BY FRED FEINSTEIN* I. THE CHANGE OF FOCUS After decades of declining union density there are indications that at least some unions are getting smarter about their efforts to increase membership. For much of the late 1970s, ’80s, and early ’90s, the labor movement focused on legislative reform as the pri- mary means of reversing its fortune. Unions viewed the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) as failing to protect workers’ right to organize unions, much less encouraging the process of collective bargaining, the law’s stated purpose.1 Yet notwithstanding the widely recognized shortcomings of the law, repeated attempts to amend the NLRA over the past thirty years failed to garner suffi- cient support to pass Congress.2 During the Clinton presidency some labor unions were optimistic that administrative reform and National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) members, who were more supportive of the NLRA’s objectives, would enhance the ability of unions to grow.