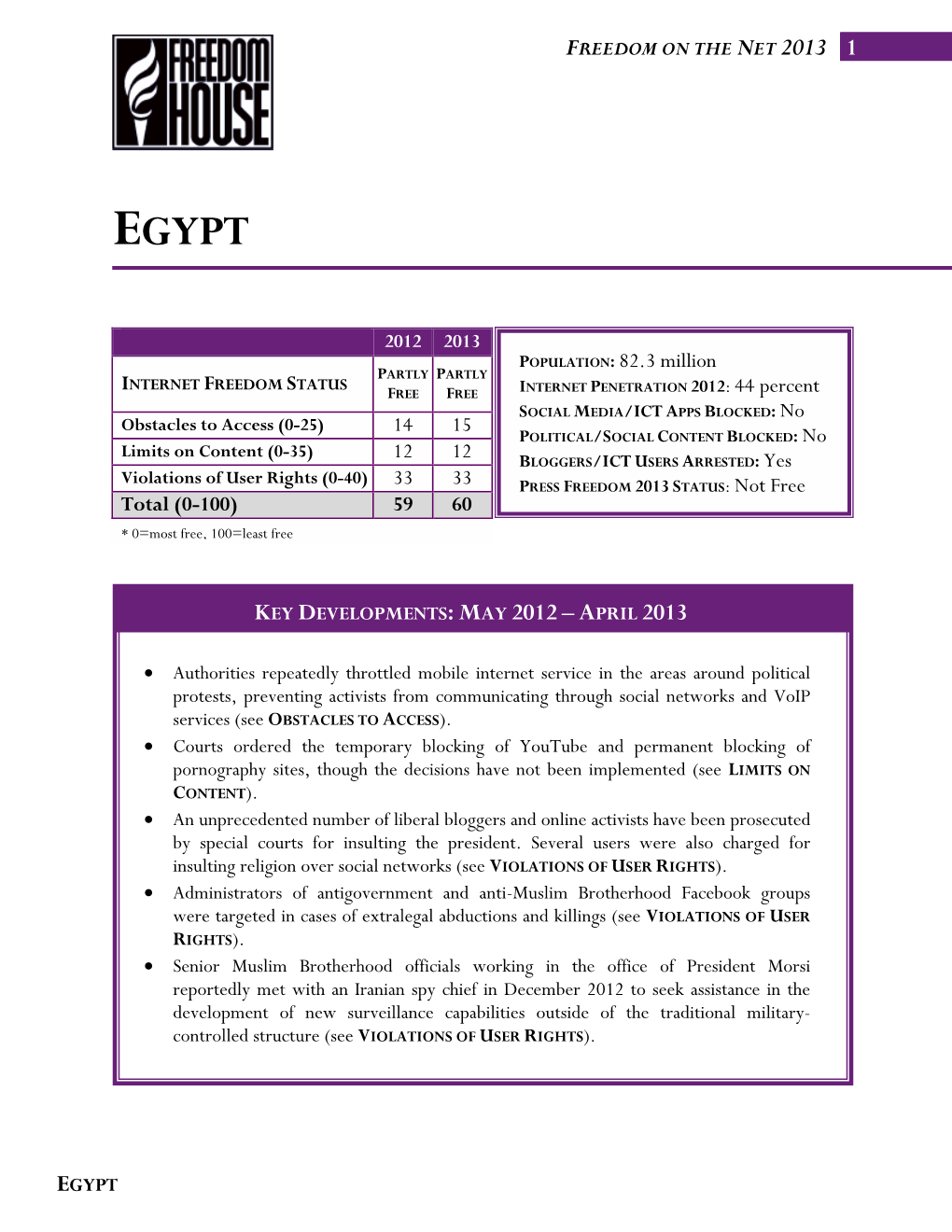

82.3 Million PRESS FREEDOM 2013 STATUS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Women and Participation in the Arab Uprisings: a Struggle for Justice

Distr. LIMITED E/ESCWA/SDD/2013/Technical Paper.13 26 December 2013 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH ECONOMIC AND SOCIAL COMMISSION FOR WESTERN ASIA (ESCWA) WOMEN AND PARTICIPATION IN THE ARAB UPRISINGS: A STRUGGLE FOR JUSTICE New York, 2013 13-0381 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This paper constitutes part of the research conducted by the Social Participatory Development Section within the Social Development Division to advocate the principles of social justice, participation and citizenship. Specifically, the paper discusses the pivotal role of women in the democratic movements that swept the region three years ago and the challenges they faced in the process. The paper argues that the increased participation of women and their commendable struggle against gender-based injustices have not yet translated into greater freedoms or increased political participation. More critically, in a region dominated by a patriarchal mindset, violence against women has become a means to an end and a tool to exercise control over society. If the demands for bread, freedom and social justice are not linked to discourses aimed at achieving gender justice, the goals of the Arab revolutions will remain elusive. This paper was co-authored by Ms. Dina Tannir, Social Affairs Officer, and Ms. Vivienne Badaan, Research Assistant, and has benefited from the overall guidance and comments of Ms. Maha Yahya, Chief, Social Participatory Development Section. iii iv CONTENTS Page Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................... iii Chapter I. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................... 1 II. GENDERING ARAB REVOLUTIONS: WHAT WOMEN WANT ......................... 2 A. The centrality of gender to Arab revolutions............................................................ 2 B. Participation par excellence: Activism among Arab women.................................... 3 III. CHANGING LANES: THE STRUGGLE OVER WOMEN’S BODIES ................. -

Women's Struggle for Citizenship

OCTOBER 2017 Women’s Struggle for Citizenship: Civil Society and Constitution Making after the Arab Uprisings JOSÉ S. VERICAT Cover Photo: Marchers on International ABOUT THE AUTHORS Women’s Day, Cairo, Egypt, March 8, 2011. Al Jazeera English. JOSÉ S. VERICAT is an Adviser at the International Peace Institute. Disclaimer: The views expressed in this paper represent those of the author Email: [email protected] and not necessarily those of the International Peace Institute. IPI welcomes consideration of a wide range of perspectives in the pursuit of ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS a well-informed debate on critical policies and issues in international The author would like to thank Mohamed Elagati and affairs. Nidhal Mekki for their useful feedback. This project would not have seen the light of day without the input of dozens IPI Publications of civil society activists from Egypt, Tunisia, and Yemen, as Adam Lupel, Vice President well as several from Libya and Syria, who believed in its Albert Trithart, Associate Editor value and selflessly invested their time and energy into it. Madeline Brennan, Assistant Production Editor To them IPI is very grateful. Within IPI, Amal al-Ashtal and Waleed al-Hariri provided vital support at different stages Suggested Citation: of the project’s execution. José S. Vericat, “Women’s Struggle for Citizenship: Civil Society and IPI owes a debt of gratitude to its many donors for their Constitution Making after the Arab generous support. In particular, IPI would like to thank the Uprisings,” New York: International governments of Finland and Norway for making this Peace Institute, October 2017. publication possible. -

Petition To: United Nations Working

PETITION TO: UNITED NATIONS WORKING GROUP ON ARBITRARY DETENTION Mr Mads Andenas (Norway) Mr José Guevara (Mexico) Ms Shaheen Ali (Pakistan) Mr Sètondji Adjovi (Benin) Mr Vladimir Tochilovsky (Ukraine) HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL UNITED NATIONS GENERAL ASSEMBLY COPY TO: UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF THE RIGHT TO FREEDOM OF OPINION AND EXPRESSION, MR DAVID KAYE; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE RIGHTS TO FREEDOM OF PEACEFUL ASSEMBLY AND OF ASSOCIATION, MR MAINA KIAI; UNITED NATIONS SPECIAL RAPPORTEUR ON THE SITUATION OF HUMAN RIGHTS DEFENDERS, MR MICHEL FORST. in the matter of Alaa Abd El Fattah (the “Petitioner”) v. Egypt _______________________________________ Petition for Relief Pursuant to Commission on Human Rights Resolutions 1997/50, 2000/36, 2003/31, and Human Rights Council Resolutions 6/4 and 15/1 Submitted by: Media Legal Defence Initiative Electronic Frontier Foundation The Grayston Centre 815 Eddy Street 28 Charles Square San Francisco CA 94109 London N1 6HT BASIS FOR REQUEST The Petitioner is a citizen of the Arab Republic of Egypt (“Egypt”), which acceded to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (“ICCPR”) on 14 January 1982. 1 The Constitution of the Arab Republic of Egypt 2014 (the “Constitution”) states that Egypt shall be bound by the international human rights agreements, covenants and conventions it has ratified, which shall have the force of law after publication in accordance with the conditions set out in the Constitution. 2 Egypt is also bound by those principles of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (“UDHR”) that have acquired the status of customary international law. -

In May 2011, Freedom House Issued a Press Release Announcing the Findings of a Survey Recording the State of Media Freedom Worldwide

Media in North Africa: the Case of Egypt 10 Lourdes Pullicino In May 2011, Freedom House issued a press release announcing the findings of a survey recording the state of media freedom worldwide. It reported that the number of people worldwide with access to free and independent media had declined to its lowest level in over a decade.1 The survey recorded a substantial deterioration in the Middle East and North Africa region. In this region, Egypt suffered the greatest set-back, slipping into the Not Free category in 2010 as a result of a severe crackdown preceding the November 2010 parliamentary elections. In Tunisia, traditional media were also censored and tightly controlled by government while internet restriction increased extensively in 2009 and 2010 as Tunisians sought to use it as an alternative field for public debate.2 Furthermore Libya was included in the report as one of the world’s worst ten countries where independent media are considered either non-existent or barely able to operate and where dissent is crushed through imprisonment, torture and other forms of repression.3 The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Arab Knowledge Report published in 2009 corroborates these findings and view the prospects of a dynamic, free space for freedom of thought and expression in Arab states as particularly dismal. 1 Freedom House, (2011): World Freedom Report, Press Release dated May 2, 2011. The report assessed 196 countries and territories during 2010 and found that only one in six people live in countries with a press that is designated Free. The Freedom of the Press index assesses the degree of print, broadcast and internet freedom in every country, analyzing the events and developments of each calendar year. -

1 During the Opening Months of 2011, the World Witnessed a Series Of

FREEDOM HOUSE Freedom on the Net 2012 1 EGYPT 2011 2012 Partly Partly POPULATION: 82 million INTERNET FREEDOM STATUS Free Free INTERNET PENETRATION 2011: 36 percent Obstacles to Access (0-25) 12 14 WEB 2.0 APPLICATIONS BLOCKED: Yes NOTABLE POLITICAL CENSORSHIP: No Limits on Content (0-35) 14 12 BLOGGERS/ ICT USERS ARRESTED: Yes Violations of User Rights (0-40) 28 33 PRESS FREEDOM STATUS: Partly Free Total (0-100) 54 59 * 0=most free, 100=least free NTRODUCTION I During the opening months of 2011, the world witnessed a series of demonstrations that soon toppled Hosni Mubarak’s 30-year presidency. The Egyptian revolution received widespread media coverage during the Arab Spring not only because of Egypt’s position as a main political hub in the Middle East and North Africa, but also because activists were using different forms of media to communicate the events of the movement to the world. While the Egyptian government employed numerous tactics to suppress the uprising’s roots online—including by shutting down internet connectivity, cutting off mobile communications, imprisoning dissenters, blocking media websites, confiscating newspapers, and disrupting satellite signals in a desperate measure to limit media coverage—online dissidents were able to evade government pressure and spread their cause through social- networking websites. This led many to label the Egyptian revolution the Facebook or Twitter Revolution. Since the introduction of the internet in 1993, the Egyptian government has invested in internet infrastructure as part of its strategy to boost the economy and create job opportunities. The Telecommunication Act was passed in 2003 to liberalize the private sector while keeping government supervision and control over information and communication technologies (ICTs) in place. -

Youth and the 25Th Revolution in Egypt: Agents of Change and Its Multiple Meanings

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by AUC Knowledge Fountain (American Univ. in Cairo) American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2012 Youth and the 25th Revolution in Egypt: agents of change and its multiple meanings Dina El Sharnouby Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation El Sharnouby, D. (2012).Youth and the 25th Revolution in Egypt: agents of change and its multiple meanings [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1131 MLA Citation El Sharnouby, Dina. Youth and the 25th Revolution in Egypt: agents of change and its multiple meanings. 2012. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/1131 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Humanities and Social Sciences Youth and the 25th Revolution in Egypt: Agents of Change and its Multiple Meanings A Thesis Submitted to The Department of Sociology, Anthropology, Psychology, and Egyptology In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts In Sociology-Anthropology By Dina El- Sharnouby Under the Supervision of Dr. Hanan Sabea January 2012 The American University in Cairo Youth and the 25th Revolution in Egypt: Agents of Change and its Multiple Meanings A Thesis Submitted by Dina El- Sharnouby To the Sociology/Anthropology Program January 2012 In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts Has been approved by Dr. -

Facebook Revolution": Exploring the Meme-Like Spread of Narratives During the Egyptian Protests

It was a "Facebook revolution": Exploring the meme-like spread of narratives during the Egyptian protests. Fue una "Revolución de Facebook": Explorando la narrativa de los meme difundidos durante las protestas egipcias. Summer Harlow1 Recibido el 14 de mayo de 2013- Aceptado el 22 de julio de 2013 ABSTRACT: Considering online social media’s importance in the Arab Spring, this study is a preliminary exploration of the spread of narratives via new media technologies. Via a textual analysis of Facebook comments and traditional news media stories during the 2011 Egyptian uprisings, this study uses the concept of “memes” to move beyond dominant social movement paradigms and suggest that the telling and re-telling, both online and offline, of the principal narrative of a “Facebook revolution” helped involve people in the protests. Keywords: Activism, digital media, Egypt, social media, social movements. RESUMEN: Éste es un estudio preliminar sobre el rol desempeñado por un estilo narrativo de los medios sociales, conocido como meme, durante la primavera árabe. Para ello, realiza un análisis textual de los principales comentarios e historias vertidas en Facebook y retratadas en los medios tradicionales, durante las protestas egipcias de 2011. En concreto, este trabajo captura los principales “memes” de esta historia, en calidad de literatura principal de este movimiento social y analiza cómo el contar y el volver a contar estas historias, tanto en línea como fuera de línea, se convirtió en un estilo narrativo de la “revolución de Facebook” que ayudó a involucrar a la gente en la protesta. Palabras claves: Activismo, medios digitales, Egipto, medios sociales, movimientos sociales. -

Palgrave Studies in Young People and Politics

Palgrave Studies in Young People and Politics Series Editors James Sloam Department of Politics and International Relations Royal Holloway, University of London Egham, UK Constance Flanagan School of Human Ecology University of Wisconsin–Madison Madison, WI, USA Bronwyn Hayward School of Social and Political Sciences University of Canterbury Christchurch, New Zealand Over the past few decades, many democracies have experienced low or falling voter turnout and a sharp decline in the members of mainstream political parties. These trends are most striking amongst young people, who have become alienated from mainstream electoral politics in many countries across the world. Young people are today faced by a particu- larly tough environment. From worsening levels of child poverty, to large increases in youth unemployment, to cuts in youth services and educa- tion budgets, public policy responses to the fnancial crisis have placed a disproportionate burden on the young. This book series will provide an in-depth investigation of the changing nature of youth civic and political engagement. We particularly welcome contributions looking at: • Youth political participation: for example, voting, demonstrations, and consumer politics • The engagement of young people in civic and political institutions, such as political parties, NGOs and new social movements • The infuence of technology, the news media and social media on young people’s politics • How democratic innovations, such as social institutions, electoral reform, civic education, can rejuvenate democracy • The civic and political development of young people during their transition from childhood to adulthood (political socialisation) • Young people’s diverse civic and political identities, as defned by issues of gender, class and ethnicity • Key themes in public policy affecting younger citizens—e.g. -

The Interaction Between Citizen Media and the Mainstream Media Media Organisation in Egypt During 2011, 2012 & 2013

BIRMINGHAM CITY UNIVERSITY The Interaction Between Citizen Media and the Mainstream Media Media Organisation in Egypt during 2011, 2012 & 2013 77,000 Words Noha Atef Supervisors: Prof. Tim Wall Dr. Dima Saber Submitted to the Faculty of Art, Design and Media at Birmingham City University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy I declare that this is a true copy of the examined manuscript of my PhD thesis in 17th January, 2017, which was further submitted on 10th March, 2017 with minor changes approved by the examiners. 1 Abstract THE INTERACTION BETWEEN CITIZEN MEDIA AND THE MAINSTREAM MEDIA Media Organisation of Egypt during 2011, 2012 & 2013 This research explores the mutual influences between citizen media and the mainstream media, through studying two phenomena occurred in Egypt during the years 2011, 2012 and 2013; which are the institutionalisation of citizen journalism and the employment of a number of citizen journalists in the mainstream media. The thesis answers the question: What is the nature of interaction between citizen media and the mainstream media? I argue that the citizen media -mainstream media interaction is driven by the medium, which is the social media, the media organizer; or the individuals who control the media outlet, either by having editorial authority, such as Editors-in-chief, or owning it. In addition, the mass media are another driver of the interaction between citizen media and the mainstream media. Plus, the relationship between the citizens of the state and the political regime too, it influence the convergence and divergence of citizen media and the mainstream media. -

Playing with Fire. the Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian

Playing with Fire.The Muslim Brotherhood and the Egyptian Leviathan Daniela Pioppi After the fall of Mubarak, the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) decided to act as a stabilising force, to abandon the street and to lend democratic legiti- macy to the political process designed by the army. The outcome of this strategy was that the MB was first ‘burned’ politically and then harshly repressed after having exhausted its stabilising role. The main mistakes the Brothers made were, first, to turn their back on several opportunities to spearhead the revolt by leading popular forces and, second, to keep their strategy for change gradualist and conservative, seeking compromises with parts of the former regime even though the turmoil and expectations in the country required a much bolder strategy. Keywords: Egypt, Muslim Brotherhood, Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, Arab Spring This article aims to analyse and evaluate the post-Mubarak politics of the Muslim Brotherhood (MB) in an attempt to explain its swift political parable from the heights of power to one of the worst waves of repression in the movement’s history. In order to do so, the analysis will start with the period before the ‘25th of January Revolution’. This is because current events cannot be correctly under- stood without moving beyond formal politics to the structural evolution of the Egyptian system of power before and after the 2011 uprising. In the second and third parts of this article, Egypt’s still unfinished ‘post-revolutionary’ political tran- sition is then examined. It is divided into two parts: 1) the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces (SCAF)-led phase from February 2011 up to the presidential elections in summer 2012; and 2) the MB-led phase that ended with the military takeover in July 2013 and the ensuing violent crackdown on the Brotherhood. -

The European Union Delegation to Egypt

News Coverage prepared for: The European Union delegation to Egypt . Disclaimer: “This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of this document are the sole responsibility of authors of articles and under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of IPSOS or the European Union.” 1 . Thematic Headlines Domestic Scene Egyptians Reject Civil Disobedience Egypt’s Military warns of plots on Eve of Strike Foreign Funding Investigations Reveal Plots to Divide the Country Hundreds Protest Military Rule on ‘Friday of Departure’ MB Ready to Form National Coalition Government Port Said Fact-Finding Committee Holds Fans Responsible Congress Delegation to Visit Egypt This Week MP Threatens To Tender His Resignation Egypt Bars British Woman from Leaving Country Shura Elections Second Phase In Mubarak Trial, Defense Arguments End Thursday IMF Spokesperson Denies Meeting SCAF Delegation Local Development Minister: Civil Disobedience Calls Are Destructive SCAF Challenges FJP US Military Delegation Arrives to Egypt US State Department: SCAF Not Responsible For NGO Raids Officers Accused of Torture Stand Trial Tomorrow NDI Trained MB and Salafi Candidates Al-Gama’a Al-Islamiyah Demands Drafting the Constitution First Mubarak Accused of High Treason 2 Newspapers (11/02/2012) Pages: 1, 3, 4, 5, 16 Authors: Ahram Correspondents Egyptians Reject Civil Disobedience On the anniversary of Mubarak's ouster, opinion is divided between those supporting a general strike and others who see it a downward spiral towards civil disobedience. However, almost all political forces reject the calls for a civil disobedience. Islamic forces rejected both; strikes and civil disobedience, for their gravity on the state’s economy. -

The Most Prominent Violations of Press and Media Freedom in Egypt During 2017

Annual Report on: Freedom of Press and Media in Egypt 2017 Annual on: Freedom of PRreses apndo Merdtia in Egypt 2017 Conducted by Ahmed Abo Elmagd Reviewed by Ahmed Ragab Cover designed by Ahmed Sobhy Published year 2017 Annual Report on: Freedom of Press and Media in Egypt 2017 The Egyptian Center for Public Policy Studies (ECPPS) is a non-governmental, non- party and non-profit organization .It is mission is to propose public policies that aim at reforming the Egyptian legal and economic systems. ECPPS’s goal is to enhance the principles of free market, individual freedom and the rule of law. The Egyptian Center for Public Policy Studies (ECPPS) 1 Annual Report on: Freedom of Press and Media in Egypt 2017 In 2017, the Egyptian Center for Public Policies Studies issues a monthly monitoring to measure (Legislative climate, political climate, economic climate, media performance and civil society role) in regard to freedom of media and journalism in Egypt, in trying to stand on events, changes, violations which happen and effect on media and journalism statement in Egypt. The Egyptian Center for Public Policies Studies held general interviews and conferences with the participation of many parties and different entities (members of Parliament, members of Press Syndicate, researchers and members of media and journalism councils) just to review, present important events and actors observed over the year. This report includes an “annual detailed report for the statement of media and journalism in Egypt in 2017”. Important events and changes which affected negatively or positively in the climate of freedom of press and media work in Egypt in 2017 in addition to precise recommendations for decision makers based on these events and changes to improve the climate of media and journalism in Egypt.