The Poetical Works of Sir Walter Scott, Bart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winckley Square Around Here’ the Geography Is Key to the History Walton

Replica of the ceremonial Roman cavalry helmet (c100 A.D.) The last battle fought on English soil was the battle of Preston in unchallenged across the bridge and began to surround Preston discovered at Ribchester in 1796: photo Steve Harrison 1715. Jacobites (the word comes from the Latin for James- town centre. The battle that followed resulted in far more Jacobus) were the supporters of James, the Old Pretender; son Government deaths than of Jacobites but led ultimately to the of the deposed James II. They wanted to see the Stuart line surrender of the supporters of James. It was recorded at the time ‘Not much history restored in place of the Protestant George I. that the Jacobite Gentlemen Ocers, having declared James the King in Preston Market Square, spent the next few days The Jacobites occupied Preston in November 1715. Meanwhile celebrating and drinking; enchanted by the beauty of the the Government forces marched from the south and east to women of Preston. Having married a beautiful woman I met in a By Steve Harrison: Preston. The Jacobites made no attempt to block the bridge at Preston pub, not far from the same market square, I know the Friend of Winckley Square around here’ The Geography is key to the History Walton. The Government forces of George I marched feeling. The Ribble Valley acts both as a route and as a barrier. St What is apparent to the Friends of Winckley Square (FoWS) is that every aspect of the Leonard’s is built on top of the millstone grit hill which stands between the Rivers Ribble and Darwen. -

The History of Scotland from the Accession of Alexander III. to The

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT LOS ANGELES THE GIFT OF MAY TREAT MORRISON IN MEMORY OF ALEXANDER F MORRISON THE A 1C MEMORIAL LIBRARY HISTORY OF THE HISTORY OF SCOTLAND, ACCESSION OF ALEXANDEB III. TO THE UNION. BY PATRICK FRASER TYTLER, ** F.RS.E. AND F.A.S. NEW EDITION. IN TEN VOLUMES. VOL. X. EDINBURGH: WILLIAM P. NIMMO. 1866. MUEKAY AND OIBB, PUINTERS. EDI.VBUKOII V.IC INDE X. ABBOT of Unreason, vi. 64 ABELARD, ii. 291 ABERBROTHOC, i. 318, 321 ; ii. 205, 207, 230 Henry, Abbot of, i. 99, Abbots of, ii. 206 Abbey of, ii. 205. See ARBROATH ABERCORN. Edward I. of England proceeds to, i. 147 Castle of, taken by James II. iv. 102, 104. Mentioned, 105 ABERCROMBY, author of the Martial Achievements, noticed, i. 125 n.; iv. 278 David, Dean of Aberdeen, iv. 264 ABERDEEN. Edward I. of England passes through, i. 105. Noticed, 174. Part of Wallace's body sent to, 186. Mentioned, 208; ii. Ill, n. iii. 148 iv. 206, 233 234, 237, 238, 248, 295, 364 ; 64, ; 159, v. vi. vii. 267 ; 9, 25, 30, 174, 219, 241 ; 175, 263, 265, 266 ; 278, viii. 339 ; 12 n.; ix. 14, 25, 26, 39, 75, 146, 152, 153, 154, 167, 233-234 iii. Bishop of, noticed, 76 ; iv. 137, 178, 206, 261, 290 ; v. 115, n. n. vi. 145, 149, 153, 155, 156, 167, 204, 205 242 ; 207 Thomas, bishop of, iv. 130 Provost of, vii. 164 n. Burgesses of, hanged by order of Wallace, i. 127 Breviary of, v. 36 n. Castle of, taken by Bruce, i. -

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper

Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes Contents 1 Visiting the Exhibition 2 The Exhibition 3 Answers to the Trail Page 1 – Family Tree Page 2 – 1689 (James VII and II) Page 3 – 1708 (James VIII and III) Page 4 – 1745 (Bonnie Prince Charlie) 4 After your visit 5 Additional Resources National Museums Scotland Scottish Charity, No. SC011130 illustrations © Jenny Proudfoot www.jennyproudfoot.co.uk Bonnie Prince Charlie and the Jacobites Teacher & Adult Helper Notes 1 Introduction Explore the real story of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, better known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and the rise and fall of the Jacobites. Step into the world of the Royal House of Stuart, one dynasty divided into two courts by religion, politics and war, each fighting for the throne of thethree kingdoms of Scotland, England and Ireland. Discover how four Jacobite kings became pawns in a much wider European political game. And follow the Jacobites’ fight to regain their lost kingdoms through five challenges to the throne, the last ending in crushing defeat at the Battle of Culloden and Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape to the Isle of Skye and onwards to Europe. The schools trail will help your class explore the exhibition and the Jacobite story through three key players: James VII and II, James VIII and III and Bonnie Prince Charlie. 1. Visiting the Exhibition (Please share this information with your adult helpers) Page Character Year Exhibition sections Important information 1 N/A N/A The Stuart Dynasty and the Union of the Crowns • Food and drink is not permitted 2 James VII 1688 Dynasty restored, Dynasty • Photography is not allowed and II divided, A court in exile • When completing the trail, ensure pupils use a pencil 3 James VIII 1708- The challenges of James VIII and III 1715 and III, All roads lead to Rome • You will enter and exit via different doors. -

GIPE-002620-Contents.Pdf (934.5Kb)

Dhallanjayarao Ga(\gil·Librar Illn~ m~ Ina 1111 11111 IRII Inlill GIPE-PUNE-:Q02620 lHE STORY OF THE" NATIONS " . SUBSCRIPTION . EDmON " II· ~be ~tOt1? of tbe Jaations SCOTLAND. , .. THE STORY OF THE NATION S.· I. ROn By ARTHUR GILMAN, 30. THE BYZANTINE EMPIRE. M.A. By c. W. C. OMAN . .. THE JEWs. By Prof. J. K. 31. SICILY: Phmnician, Greek HOSMER. and Reman. By the late 3. GERMANY. By Rev. S. BARING- Prof. E. A. FREEMAN. GOULD, M.A. 3" THE TUSCAN REPUBLICS. 4. CARTHAGE. By Prof. ALFRED By BELLA DUFFY. J. CHURCH. 33. POLAND. By W. R. MORFILL, 5. ALEXANDER'S EMPIRE. By M.A. Prof. J. P. MAHAFFY. 3+ PARTWA. By Prof. GEORGE 6. THE MOORS IN SPAIN. By RAWLINSON. STANLEY LANE-POOLE. 35. AUSTRALIAN COMMON- 7. ANCIENT EGYl'T. By Prof. WEALTH. By GREVILLE GEORGF. RAWLINSON. TREGARTUEN. 8. HUNGARY. By Prof. ARMINIUS 36. SPAIN. By H. E. WATTS., VAMBERY. 37. JAPAN. By DAVID MURRAY, 9. THE SARACENS. By ARTHUR Ph.D. GILMAN, M.A. 38. SOUTH AFRICA. By GEORGI< 10. IRELAND. By the Hon. EMILY M. THEAL. LAWI.ESS. 39- VENICE. By ALETHEA WIEL. II. CHALDEA. By ZENAioE A. 40. THE CRUSADES. By T. A. RAGOZIN. ARCHER and C. L. KINGS' I •• THE GOTHS. By HENRY BRAD FORD. LEY. 41. VEDIC INDIA. By Z. A. RA' 13. ASSYRIA. By ZEN AiDE A. RA COZIN. • GOZIN. 4'. WEST INDIES AND THE 14. TURKEY. By STANLEY LANE SPANISH MAIN. By JAMES POOLE. RODWAY. IS. HOLLAND. By Prof. J- .E. 43. BOHEMIA. By C. EDMUND THOROLD ROGERS. MAURICE. 16. MEDIEVAL FRANCE. -

Insert Document Title What's New in England 2015 and Beyond for The

Insert Document Title Here What’s New in England 2015 and Beyond For the most up to date guide, please check: http://www.visitengland.org/media/resources/whats_new.aspx 1. Accommodation Bouja by Hoseasons, Devon and Hampshire From 30 January Hoseasons will be introducing ‘affordable luxury breaks’ under new brand Bouja. Set across six countryside and coastal locations, Bouja will offer holiday homes with a deck, patio or private garden, as well as amenities including a flat-screen TV. Bike hire, nature trails and great quality bistros and restaurants will be offered nearby, while quirkier spaces will be provided by the designer Bouja Boutique. Beach Cove Coastal Retreat will be the first location to open, with others following throughout Q1. http://www.hoseasons.co.uk/ The Hospital Club, London January The former hospital turned ‘creative hub’, The Hospital Club, has now added 15 hotel rooms to its Covent Garden venue. The rooms boast sumptuous interiors and stained glass by Russell Sage studios, providing guests with a home away from home. Suites also include a private terrace, rainforest showers and lounge area. Rooms start from £180 per night. http://www.thehospitalclub.com The 25 Boutique, Torquay January A luxury 5 star boutique B&B, is located a 10 minute walk from the centre of Torquay and close by to the Riviera International Centre and Torre abbey. Each room is individually designed and provides different sizes and amenities. http://www.the25.uk/ The Seaside Boarding House, Restaurant & Bar, Burton Bradstock February/March The Seaside Boarding House Restaurant and Bar is set on the cliffs overlooking the sweep of Dorset’s famous Chesil Beach and the wide expanse of Lyme Bay. -

John Menzies Baillie, Chartered Accountant: Nine Hundred Years of Landownership in France, England, Scotland, and America Tom Lee

The Accounting Historians Notebook Volume 28 Article 6 Number 1 April 2005 2005 John Menzies Baillie, chartered accountant: Nine hundred years of landownership in France, England, Scotland, and America Tom Lee Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_notebook Part of the Accounting Commons, and the Taxation Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Tom (2005) "John Menzies Baillie, chartered accountant: Nine hundred years of landownership in France, England, Scotland, and America," The Accounting Historians Notebook: Vol. 28 : No. 1 , Article 6. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/aah_notebook/vol28/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Archival Digital Accounting Collection at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Accounting Historians Notebook by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lee: John Menzies Baillie, chartered accountant: Nine hundred years of landownership in France, England, Scotland, and America John Menzies Baillie, Chartered Accountant: Nine Hundred Years of Landownership in France, England, Scotland, and America by Tom Lee Professor Emeritus, University of Alabama The accounting history literature Lanarkshire. He also died there in contains books and papers dealing 1886. In the intervening 60 years, with the foundation of modern pub- he had an unexceptional career as a lic accountancy in Scotland in the public accountant in Edinburgh be- last half of the nineteenth century fore retiring to Culter Allers. His (e.g. Kedslie, 1990; Lee, 2000; place in history rests exclusively on Walker, 1995). Most deal with his membership in the group of 61 events, circumstances, and conse- Edinburgh accountants who formed quences of the foundation but few the first modern institution of pub- describe the founders other than in lic accountancy in 1853 - the Insti- terms of generic analyses of ori- tute of Accountants in Edinburgh, gins. -

Clan SEMPILL

Clan SEMPILL ARMS Argent, a chevron chequy Gules and of the First between three hunting horns sable garnished and stringed of the Second CREST A stag’s head Argent attired with ten tynes Azure and collard with a prince’s crown Or MOTTO Keep tryst SUPPORTERS Two greyhounds Argent, collared Gules STANDARD The Arms in the hoist and of two tracts Gules and Argent, upon which is depicted three times the Crest, ensigned of a Baron’s coronet along with the Motto ‘Keep tryst’ in letters Gules upon two transverse bands Or A name known in Renfrewshire from the twelfth century, its origin is obscure. The suggestion that it is a corruption of ‘St Paul’ seem unlikely, as is the tradition that the 1st of the name had a reputation for being humble or simple. Robert de Sempill witnessed a charter to Paisley Abbey around 1246, and later, as chamberlain of Renfrew, a charter of the Earl of Lennox. His two sons, Robert and Thomas, supported Robert the Bruce, and both were rewarded by the king for their services. The elder son received all the lands around Largs in Ayrshire which had been confiscated from the Balliols. Thomas received a grant of half of the lands of Longniddry. The lands of Eliotstoun, which became the territorial designation of the chiefly line, were acquired prior to 1344. Sir Thomas Sempill of Eliotstoun fell at the Battle of Sauchiefurn fighting for James III in June 1488. His only son, John, succeeded to the family estates, and early in the reign of James IV – probably in 14188 – he was ennobled with the title, Lord Sempill. -

A Short Essay About Preston Written by Desiree Le

qwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwerty uiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasd fghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzx cvbnmqwertyuPrestoniopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopThea sdevelopmentdfghjk ofl za cityxc throughoutvbnm qwertyui the centuries opasdfghjklzxcvDesireeb nLe Clairem qSG E/1wertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwEnglischer beit Frauyu Kaphegyiiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxc vbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmq wertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyui opasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfg hjklzxcvbnmrtyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbn mqwertyuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwert yuiopasdfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopas dfghjklzxcvbnmqwertyuiopasdfghjklz Inhaltsverzeichnis: General Information S. 3 Pre-industrial era “ How the city changed during the S. 4 industrialization Developments in the 20th century S. 5 The city today S. 6 Pictures S. 7 Eigenständigkeitserklärung S. 10 Literatur- und Quellenverzeichnis S. 11 Anhang S. 12 2 Preston The development of a city throughout the centuries 1. General information Preston is a city in the shire county of Lancashire, in the North West of England in the sovereign state of the United Kingdom. It’s “located on the north bank of the River Ribble.” (picture 1) 114,300 people live there (ONS, June 2008).1 With 142.22km² it’s about 65km² smaller than Stuttgart. 2 “… The name Preston is derived from Old English words meaning “Priest settlement” and in the Domesday Book appears as Prestune.” 3 The Domesday Book was completed in 1086 and it’s a collection of the great survey of England and Wales. 4 2. Pre-industrial era (shortly before the IR) The plague in November 1631 killed 1100 people in Preston in 12 month. The civil war from 1630 to 1650 and the Battle of Preston in 1648 have been very bad for the town, too. 5 The Jacobite Battle in November 1715 describes the battle, when the troops of King George defeated a Jacobite Army of 2,000 soldiers in the Church Street of Preston. -

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans Designation

The Inventory of Historic Battlefields – Battle of Prestonpans The Inventory of Historic Battlefields is a list of nationally important battlefields in Scotland. A battlefield is of national importance if it makes a contribution to the understanding of the archaeology and history of the nation as a whole, or has the potential to do so, or holds a particularly significant place in the national consciousness. For a battlefield to be included in the Inventory, it must be considered to be of national importance either for its association with key historical events or figures; or for the physical remains and/or archaeological potential it contains; or for its landscape context. In addition, it must be possible to define the site on a modern map with a reasonable degree of accuracy. The aim of the Inventory is to raise awareness of the significance of these nationally important battlefield sites and to assist in their protection and management for the future. Inventory battlefields are a material consideration in the planning process. The Inventory is also a major resource for enhancing the understanding, appreciation and enjoyment of historic battlefields, for promoting education and stimulating further research, and for developing their potential as attractions for visitors. Designation Record and Full Report Contents Name - Context Alternative Name(s) Battlefield Landscape Date of Battle - Location Local Authority - Terrain NGR Centred - Condition Date of Addition to Inventory Archaeological and Physical Date of Last Update Remains and Potential -

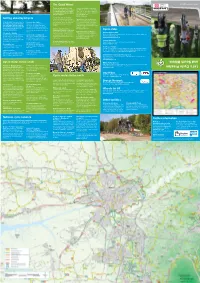

Let's Cycle Preston and South Ribble

The Guild Wheel www.lancashire.gov.uk The Preston Guild Wheel is a 21 mile Stop at the floating Visitor Village where circular cycle route round Preston opened you will find a cafe, shops and information comms: xxxx to celebrate 2012 Guild. Preston Guild centre. There are lakes, hides, walking trails occurs every 20 years and has a history and a play area. The reserve is owned by going back 700 years. Lancashire Wildlife Trust. www.brockholes.org The Guild Wheel links the city with the Getting about by bicycle surrounding countryside and river corridor. Preston Docks – Stop for a drink at one It takes you through the different landscapes of the cafes and pubs by the dockside or Did you know that there are now over 75 Cycle to the station that surround the city, including riverside ride down to the lock gates. When opened km of traffic free cycle paths in Preston Fed up with motorway driving. More and meadows, historic parks and ancient in 1892 it was the largest dock basin in and South Ribble? With new routes like more people are cycling to the station woodland. Europe employing over 500 people. Today the Guild Wheel and 20 mph speed limits and catching the train. A new cycle hub is the dock is a marina. it is becoming more attractive to get opening at Preston station in Summer 2016. Attractions along the route include: www.prestondock.co.uk around the area by bicycle. There is good cycle parking at other stations Avenham and Miller Parks – Ride through Cycle clubs in the area. -

John Hodgson Soldier, Surgeon, Agitator and Quaker?

220 JOHN HODGSON SOLDIER, SURGEON, AGITATOR AND QUAKER? n 1954 Alan Cole presented "More Light on John Hodgson" in relation to the Peace Testimony of 1659 and two Quaker tracts of Ithat year, "A Letter from a Member of the Army, to the Committee of Safety, and Councell of Officers of the Army" and "Love, Kindness, and due Respect".1 Cole's piece was, in part, a response to an earlier consideration of the two tracts and their authorship.2 Unlike the 1950 piece Cole convincingly argued that the John Hodgson who signed both tracts was the same man. "It would certainly be a rather striking coincidence if two writers of the same name had published tracts with such marked similarities of argument and style as we find in these two pamphlets...".3 The other key point in Cole's article was that John Hodgson the Quaker, the author of both tracts, was "a civilian in the summer of 1659 when he addressed his paper, 'Love, Kindness, and due Respect' to the restored Rump... and that he subsequently enlisted or re-enlisted in the Army".4 Although Cole was unable to detail who Hodgson the Quaker might have been the 1950 piece very briefly dismissed a Captain John Hodgson as a possible author of the two tracts.5 However a more detailed consideration of this Captain John Hodgson does suggest that he may be the author of these tracts. There are some interesting parallels between what is known of John Hodgson the Quaker author and this Captain John Hodgson, soldier.6 Captain John Hodgson entered a company of foot in Sir Thomas Fairfax's regiment in his native Yorkshire in late 1642. -

Investigating Murder, Plotting, Romance, Kidnap, Imprisonment, Escape and Execution

The story of Scotland’s most famous queen has everything: battles, INVESTIGATING murder, plotting, romance, kidnap, imprisonment, escape and execution. MARY QUEEN This resource identifies some of the key sites and aims to give teachers OF SCOTS strategies for investigating these sites with primary age pupils. Information for teachers EDUCATION INVESTIGATING HISTORIC SITES: PEOPLE 2 Mary Queen of Scots Using this resource Contents great fun – most pupils find castles and P2 Introduction ruins interesting and exciting. Some of the Using this resource This resource is for teachers investigating sites have replica objects or costumes for P3 the life of Mary Queen of Scots with their pupils to handle. Booking a visit pupils. It aims to link ongoing classroom work with the places associated with the Many of the key sites associated with Mary P4 are, because of their royal connections, in a Supporting learning and queen, and events with the historic sites teaching where they took place. good state of repair. At Stirling there is the great bonus that the rooms of the royal palace P6 NB: This pack is aimed at teachers rather are currently being restored to their 16th- Integrating a visit with than pupils and it is not intended that it century splendour. Many sites are, however, classroom studies should be copied and distributed to pupils. ruinous. Presented properly, this can be a P10 This resource aims to provide: powerful motivator for pupils: What could this Timeline: the life of hole in the floor have been used for? Can you Mary Queen of Scots • an indication of how visits to historic sites can illuminate a study of the work out how the Prestons might defend their P12 dramatic events of the life of Mary castle at Craigmillar? Can anyone see any clues Who’s who: key people Queen of Scots as to what this room used to be? Pupils should in the life of Mary Queen be encouraged at all times to ‘read the stones’ of Scots • support for the delivery of the Curriculum for Excellence and offer their own interpretations of what P14 they see around them.