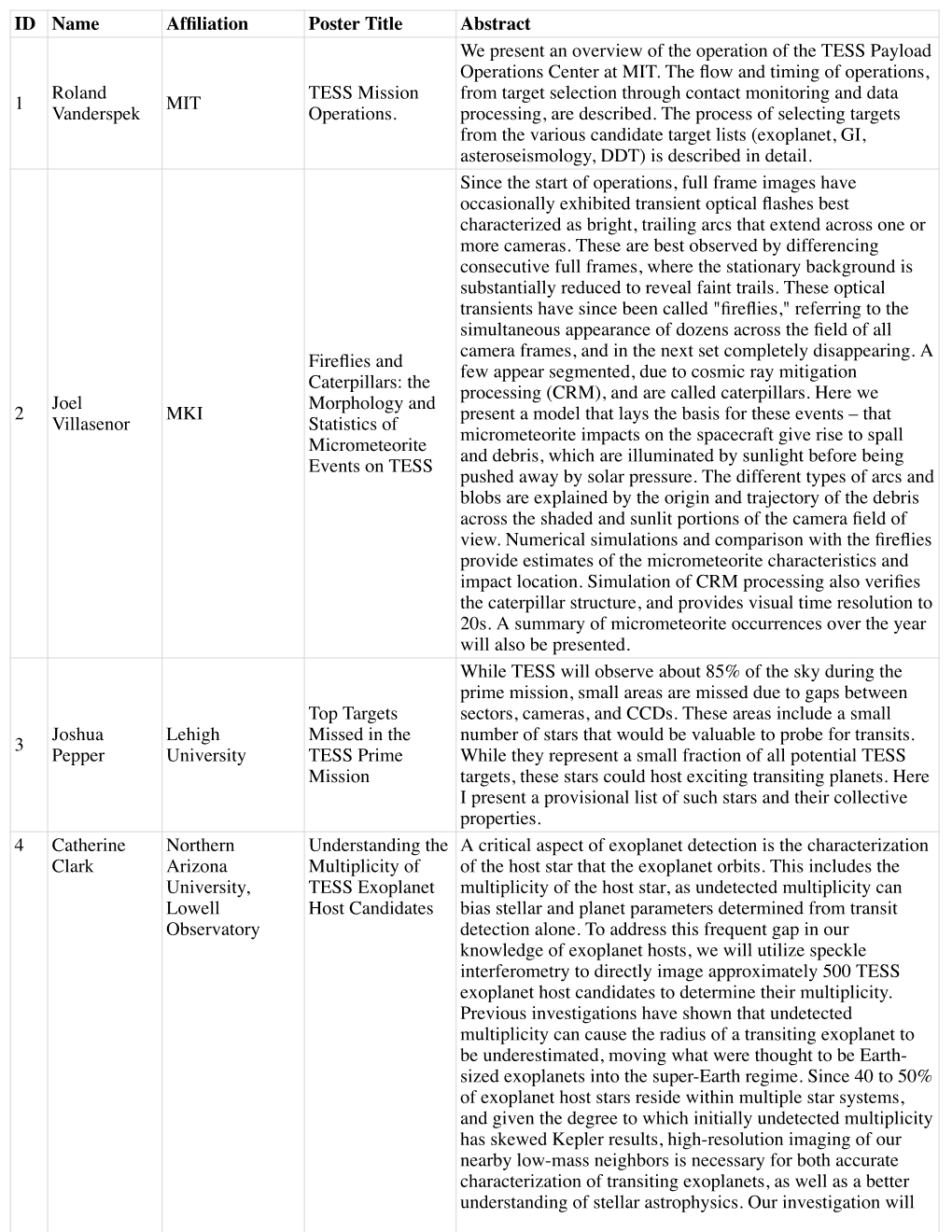

Poster Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Nearest Stars: a Guided Tour by Sherwood Harrington, Astronomical Society of the Pacific

www.astrosociety.org/uitc No. 5 - Spring 1986 © 1986, Astronomical Society of the Pacific, 390 Ashton Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94112. The Nearest Stars: A Guided Tour by Sherwood Harrington, Astronomical Society of the Pacific A tour through our stellar neighborhood As evening twilight fades during April and early May, a brilliant, blue-white star can be seen low in the sky toward the southwest. That star is called Sirius, and it is the brightest star in Earth's nighttime sky. Sirius looks so bright in part because it is a relatively powerful light producer; if our Sun were suddenly replaced by Sirius, our daylight on Earth would be more than 20 times as bright as it is now! But the other reason Sirius is so brilliant in our nighttime sky is that it is so close; Sirius is the nearest neighbor star to the Sun that can be seen with the unaided eye from the Northern Hemisphere. "Close'' in the interstellar realm, though, is a very relative term. If you were to model the Sun as a basketball, then our planet Earth would be about the size of an apple seed 30 yards away from it — and even the nearest other star (alpha Centauri, visible from the Southern Hemisphere) would be 6,000 miles away. Distances among the stars are so large that it is helpful to express them using the light-year — the distance light travels in one year — as a measuring unit. In this way of expressing distances, alpha Centauri is about four light-years away, and Sirius is about eight and a half light- years distant. -

Early Observations of the Interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov

geosciences Article Early Observations of the Interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov Chien-Hsiu Lee NSF’s National Optical-Infrared Astronomy Research Laboratory, Tucson, AZ 85719, USA; [email protected]; Tel.: +1-520-318-8368 Received: 26 November 2019; Accepted: 11 December 2019; Published: 17 December 2019 Abstract: 2I/Borisov is the second ever interstellar object (ISO). It is very different from the first ISO ’Oumuamua by showing cometary activities, and hence provides a unique opportunity to study comets that are formed around other stars. Here we present early imaging and spectroscopic follow-ups to study its properties, which reveal an (up to) 5.9 km comet with an extended coma and a short tail. Our spectroscopic data do not reveal any emission lines between 4000–9000 Angstrom; nevertheless, we are able to put an upper limit on the flux of the C2 emission line, suggesting modest cometary activities at early epochs. These properties are similar to comets in the solar system, and suggest that 2I/Borisov—while from another star—is not too different from its solar siblings. Keywords: comets: general; comets: individual (2I/Borisov); solar system: formation 1. Introduction 2I/Borisov was first seen by Gennady Borisov on 30 August 2019. As more observations were conducted in the next few days, there was growing evidence that this might be an interstellar object (ISO), especially its large orbital eccentricity. However, the first astrometric measurements do not have enough timespan and are not of same quality, hence the high eccentricity is yet to be confirmed. This had all changed by 11 September; where more than 100 astrometric measurements over 12 days, Ref [1] pinned down the orbit elements of 2I/Borisov, with an eccentricity of 3.15 ± 0.13, hence confirming the interstellar nature. -

Make a Comet Materials: Students Should First Line Their Mixing Bowls with Trash Bags

Build Your Own Comet Prep Time: 30 minutes Grades: 6-8 Lesson Time: 55 minutes Essential Questions: • What is a comet composed of? • What gives a comet its tail? • What makes a comet different from other Near-Earth Objects (NEOs)? Objectives: • Create a physical representation of a comet and its properties. • Observe distinguishable factors between comets and other NEOs. Standards: • MS – PS1-4: Develop a model that predicts and describes changes in particle motion, temperature, and state of a pure substance when thermal energy is added or removed. • CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RST.6-8.3 - Follow precisely a multistep procedure when carrying out experiments, taking measurements, or performing technical tasks. Teacher Prep: • Materials per comet: o 5 lbs. dry ice, ice chest, paper cups, towels, small container (for scooping), wooden or plastic mixing spoon, trash bag, mixing bowl, heavy work gloves, 1 tablespoon or less of starch, 1 tablespoon or less of dark corn syrup (or soda), 1 tablespoon or less of vinegar, 1 tablespoon or less of rubbing alcohol, large beaker, water, 1 c dirt/sand, 1 L of water. • Additional materials: o Hammer or mallet, paper cups, towels, flashlight, hair dryer. • Most of the dry ice needs to be in a fine powder before the students arrive, so use the hammer to do this ahead of time. There should be about 50-60% fine powder in order to hold the comet together. It is best to separate the dry ice ahead of time with towels. • This can also be done as a class demonstration. Teacher Notes/Background: • This lesson was adapted from NASA’s Make Your Own Comet activity. -

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN to BE HABITABLE? 8:15 A.M. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 A.M. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome C

Monday, November 13, 2017 WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO BE HABITABLE? 8:15 a.m. MHRGC Salons ABCD 8:15 a.m. Jang-Condell H. * Welcome Chair: Stephen Kane 8:30 a.m. Forget F. * Turbet M. Selsis F. Leconte J. Definition and Characterization of the Habitable Zone [#4057] We review the concept of habitable zone (HZ), why it is useful, and how to characterize it. The HZ could be nicknamed the “Hunting Zone” because its primary objective is now to help astronomers plan observations. This has interesting consequences. 9:00 a.m. Rushby A. J. Johnson M. Mills B. J. W. Watson A. J. Claire M. W. Long Term Planetary Habitability and the Carbonate-Silicate Cycle [#4026] We develop a coupled carbonate-silicate and stellar evolution model to investigate the effect of planet size on the operation of the long-term carbon cycle, and determine that larger planets are generally warmer for a given incident flux. 9:20 a.m. Dong C. F. * Huang Z. G. Jin M. Lingam M. Ma Y. J. Toth G. van der Holst B. Airapetian V. Cohen O. Gombosi T. Are “Habitable” Exoplanets Really Habitable? A Perspective from Atmospheric Loss [#4021] We will discuss the impact of exoplanetary space weather on the climate and habitability, which offers fresh insights concerning the habitability of exoplanets, especially those orbiting M-dwarfs, such as Proxima b and the TRAPPIST-1 system. 9:40 a.m. Fisher T. M. * Walker S. I. Desch S. J. Hartnett H. E. Glaser S. Limitations of Primary Productivity on “Aqua Planets:” Implications for Detectability [#4109] While ocean-covered planets have been considered a strong candidate for the search for life, the lack of surface weathering may lead to phosphorus scarcity and low primary productivity, making aqua planet biospheres difficult to detect. -

W359 E31 RS.Pdf

WOLF 359 "SÉCURITÉ" by Gabriel Urbina (Writer's Note: The following takes place on Day 864 of the Hephaestus Mission) INT. U.S.S. URANIA - FLIGHT DECK - 1400 HOURS We come in on the STEADY HUM of a ship's engine. There's various BEEPS and DINGS from a control console. Sharp-eared listeners might notice that things sound considerably sleeker and smoother than what we're used to. Someone TYPES into a console, and hits a SWITCH. There's a discrete burst of STATIC, followed by - JACOBI Sécurité, sécurité, sécurité. U.S.S. Hephaestus Station, this is the U.S.S. Urania. Be advised that we are on an intercept vector. Request you avoid any course corrections or exterior activity. Please advise your intentions. He hits a BUTTON. For a BEAT he just awaits the reply. JACOBI (CONT'D) Still no reply, sir. You really think someone's alive in there? I mean... look at that thing. It's only duct tape and sheer stubbornness keeping it together. KEPLER No. They're there. Rebroadcast, and transmit the command authentication codes. JACOBI Aye-aye. (hits the radio switch) Sécurité, sécurité, sécurité. U.S.S. Hephaestus, this is the U.S.S. Urania. I say again: we are on an approach vector to your current position. Authentication code: Victor-Uniform-Lima-Charlie- Alpha-November. Please advise your intentions. BEAT. And then - KRRRCH! MINKOWSKI (over radio receiver) U.S.S. Urania, this is Hephaestus Actual. Continue on current course, and use vector zero one decimal nine for your final approach. 2. JACOBI Copy that, Hephaestus Actual. -

Initial Characterization of Interstellar Comet 2I/Borisov

Initial characterization of interstellar comet 2I/Borisov Piotr Guzik1*, Michał Drahus1*, Krzysztof Rusek2, Wacław Waniak1, Giacomo Cannizzaro3,4, Inés Pastor-Marazuela5,6 1 Astronomical Observatory, Jagiellonian University, Kraków, Poland 2 AGH University of Science and Technology, Kraków, Poland 3 SRON, Netherlands Institute for Space Research, Utrecht, the Netherlands 4 Department of Astrophysics/IMAPP, Radboud University, Nijmegen, the Netherlands 5 Anton Pannekoek Institute for Astronomy, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, the Netherlands 6 ASTRON, Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy, Dwingeloo, the Netherlands * These authors contributed equally to this work; email: [email protected], [email protected] Interstellar comets penetrating through the Solar System had been anticipated for decades1,2. The discovery of asteroidal-looking ‘Oumuamua3,4 was thus a huge surprise and a puzzle. Furthermore, the physical properties of the ‘first scout’ turned out to be impossible to reconcile with Solar System objects4–6, challenging our view of interstellar minor bodies7,8. Here, we report the identification and early characterization of a new interstellar object, which has an evidently cometary appearance. The body was discovered by Gennady Borisov on 30 August 2019 UT and subsequently identified as hyperbolic by our data mining code in publicly available astrometric data. The initial orbital solution implies a very high hyperbolic excess speed of ~32 km s−1, consistent with ‘Oumuamua9 and theoretical predictions2,7. Images taken on 10 and 13 September 2019 UT with the William Herschel Telescope and Gemini North Telescope show an extended coma and a faint, broad tail. We measure a slightly reddish colour with a g′–r′ colour index of 0.66 ± 0.01 mag, compatible with Solar System comets. -

The Search for Exomoons and the Characterization of Exoplanet Atmospheres

Corso di Laurea Specialistica in Astronomia e Astrofisica The search for exomoons and the characterization of exoplanet atmospheres Relatore interno : dott. Alessandro Melchiorri Relatore esterno : dott.ssa Giovanna Tinetti Candidato: Giammarco Campanella Anno Accademico 2008/2009 The search for exomoons and the characterization of exoplanet atmospheres Giammarco Campanella Dipartimento di Fisica Università degli studi di Roma “La Sapienza” Associate at Department of Physics & Astronomy University College London A thesis submitted for the MSc Degree in Astronomy and Astrophysics September 4th, 2009 Università degli Studi di Roma ―La Sapienza‖ Abstract THE SEARCH FOR EXOMOONS AND THE CHARACTERIZATION OF EXOPLANET ATMOSPHERES by Giammarco Campanella Since planets were first discovered outside our own Solar System in 1992 (around a pulsar) and in 1995 (around a main sequence star), extrasolar planet studies have become one of the most dynamic research fields in astronomy. Our knowledge of extrasolar planets has grown exponentially, from our understanding of their formation and evolution to the development of different methods to detect them. Now that more than 370 exoplanets have been discovered, focus has moved from finding planets to characterise these alien worlds. As well as detecting the atmospheres of these exoplanets, part of the characterisation process undoubtedly involves the search for extrasolar moons. The structure of the thesis is as follows. In Chapter 1 an historical background is provided and some general aspects about ongoing situation in the research field of extrasolar planets are shown. In Chapter 2, various detection techniques such as radial velocity, microlensing, astrometry, circumstellar disks, pulsar timing and magnetospheric emission are described. A special emphasis is given to the transit photometry technique and to the two already operational transit space missions, CoRoT and Kepler. -

The University of Chicago Glimpses of Far Away

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO GLIMPSES OF FAR AWAY PLACES: INTENSIVE ATMOSPHERE CHARACTERIZATION OF EXTRASOLAR PLANETS A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE PHYSICAL SCIENCES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ASTRONOMY AND ASTROPHYSICS BY LAURA KREIDBERG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS AUGUST 2016 Copyright c 2016 by Laura Kreidberg All Rights Reserved Far away places with strange sounding names Far away over the sea Those far away places with strange sounding names Are calling, calling me. { Joan Whitney & Alex Kramer TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF FIGURES . vii LIST OF TABLES . ix ACKNOWLEDGMENTS . x ABSTRACT . xi 1 INTRODUCTION . 1 1.1 Exoplanets' Greatest Hits, 1995 - present . 1 1.2 Moving from Discovery to Characterization . 2 1.2.1 Clues from Planetary Atmospheres I: How Do Planets Form? . 2 1.2.2 Clues from Planetary Atmospheres II: What are Planets Like? . 3 1.2.3 Goals for This Work . 4 1.3 Overview of Atmosphere Characterization Techniques . 4 1.3.1 Transmission Spectroscopy . 5 1.3.2 Emission Spectroscopy . 5 1.4 Technical Breakthroughs Enabling Atmospheric Studies . 7 1.5 Chapter Summaries . 10 2 CLOUDS IN THE ATMOSPHERE OF THE SUPER-EARTH EXOPLANET GJ 1214b . 12 2.1 Introduction . 12 2.2 Observations and Data Reduction . 13 2.3 Implications for the Atmosphere . 14 2.4 Conclusions . 18 3 A PRECISE WATER ABUNDANCE MEASUREMENT FOR THE HOT JUPITER WASP-43b . 21 3.1 Introduction . 21 3.2 Observations and Data Reduction . 23 3.3 Analysis . 24 3.4 Results . 27 3.4.1 Constraints from the Emission Spectrum . -

Virtual Planetarium in Cyberstage

Virtual Planetarium in Cyb erStage Valery Burkin, Martin Gob el, Frank Hasenbrink, Stanislav Klimenko, Igor Nikitin, Henrik Tramb erend GMD { German National Research Center for Information Technology Abstract. We describ e an educational application in virtual environ- ment, intended for teaching and demonstration of basics of astronomy. The application includes 3D mo dels of 30 ob jects in the Solar System, 3200 nearby stars, a large database, containing textual descriptions of all ob jects in a scene, interactive map of constellations and to ols for search and navigation. The metho ds, needed for visualization of di erent scale astronomical ob jects in virtual environment, are describ ed. Mo dern educational pro cess actively uses the metho ds of computer graphics and scienti c visualization. Wide opp ortunities are op ened by emerging technology of virtual environments, which can be used for a creation of high interactive virtual lab oratories intended for teaching di erent disciplines. In this pap er we describ e an exp erimental course on basics of astronomy, which is delivered inside the immersive virtual environment system CyberStage, installed at GMD, and gives a p ossibility to explore interactively the Solar System and surrounding stars. The rst section presents the virtual environment system CyberStage. The second section outlines Avango, the main software comp onent driving this sys- tem. The metho ds used for mo deling of astronomical ob jects are describ ed in the third section and summarized in conclusion. 1 Cyb erStage The CyberStage [1] is CAVE-like [2] audio-visual pro jection system. It has ro om sizes (3m3m2.4m) and integrates a 4-side stereo image pro jection and 8- channel spatial sound pro jection, b oth controlled by the p osition of the user's head, followed by a tracking system (Polhemus Fastrak sensors). -

Introduction to ASTR 565 Stellar Structure and Evolution

Introduction to ASTR 565 Stellar Structure and Evolution Jason Jackiewicz Department of Astronomy New Mexico State University August 22, 2019 Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course Outline 1 Main goal 2 Structure of stars 3 Evolution of stars 4 Applications to observations 5 Overview of course Introduction to ASTR 565 Jason Jackiewicz Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course 1 Main goal 2 Structure of stars 3 Evolution of stars 4 Applications to observations 5 Overview of course Introduction to ASTR 565 Jason Jackiewicz Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course Order in the H-R Diagram!! Introduction to ASTR 565 Jason Jackiewicz Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course Motivation: Understanding the H-R Diagram Introduction to ASTR 565 Jason Jackiewicz HRD (2) HRD (3) Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course 1 Main goal 2 Structure of stars 3 Evolution of stars 4 Applications to observations 5 Overview of course Introduction to ASTR 565 Jason Jackiewicz Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course Basic structure - highly non-linear solution Introduction to ASTR 565 Jason Jackiewicz Main goal Structure of stars Evolution of stars Applications to observations Overview of course Massive-star nuclear burning Introduction -

Discovery of a Low-Mass Companion to a Metal-Rich F Star with the Marvels Pilot Project

The Astrophysical Journal, 718:1186–1199, 2010 August 1 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/718/2/1186 C 2010. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. DISCOVERY OF A LOW-MASS COMPANION TO A METAL-RICH F STAR WITH THE MARVELS PILOT PROJECT Scott W. Fleming1,JianGe1, Suvrath Mahadevan1,2,3, Brian Lee1, Jason D. Eastman4, Robert J. Siverd4, B. Scott Gaudi4, Andrzej Niedzielski5, Thirupathi Sivarani6, Keivan G. Stassun7,8, Alex Wolszczan2,3, Rory Barnes9, Bruce Gary7, Duy Cuong Nguyen1, Robert C. Morehead1, Xiaoke Wan1, Bo Zhao1, Jian Liu1, Pengcheng Guo1, Stephen R. Kane1,10, Julian C. van Eyken1,10, Nathan M. De Lee1, Justin R. Crepp1,11, Alaina C. Shelden1,12, Chris Laws9, John P. Wisniewski9, Donald P. Schneider2,3, Joshua Pepper7, Stephanie A. Snedden12, Kaike Pan12, Dmitry Bizyaev12, Howard Brewington12, Olena Malanushenko12, Viktor Malanushenko12, Daniel Oravetz12, Audrey Simmons12, and Shannon Watters12,13 1 Department of Astronomy, University of Florida, 211 Bryant Space Science Center, Gainesville, FL 326711-2055, USA; scfl[email protected]fl.edu 2 Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics, The Pennsylvania State University, 525 Davey Laboratory, University Park, PA 16802, USA 3 Center for Exoplanets and Habitable Worlds, The Pennsylvania State University, University Park, PA 16802, USA 4 Department of Astronomy, The Ohio State University, 140 West 18th Avenue, Columbus, OH 43210, USA 5 Torun´ Center for Astronomy, Nicolaus Copernicus University, ul. Gagarina 11, 87-100, Torun,´ Poland 6 Indian Institute of Astrophysics, Bangalore 560034, India 7 Department of Physics and Astronomy, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN 37235, USA 8 Department of Physics, Fisk University, 1000 17th Ave. -

Detection of Exocometary CO Within the 440 Myr Old Fomalhaut Belt: a Similar CO+CO2 Ice Abundance in Exocomets and Solar System Comets

UCLA UCLA Previously Published Works Title Detection of Exocometary CO within the 440 Myr Old Fomalhaut Belt: A Similar CO+CO2 Ice Abundance in Exocomets and Solar System Comets Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1zf7t4qn Journal Astrophysical Journal, 842(1) ISSN 0004-637X Authors Matra, L MacGregor, MA Kalas, P et al. Publication Date 2017-06-10 DOI 10.3847/1538-4357/aa71b4 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California The Astrophysical Journal, 842:9 (15pp), 2017 June 10 https://doi.org/10.3847/1538-4357/aa71b4 © 2017. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Detection of Exocometary CO within the 440 Myr Old Fomalhaut Belt: A Similar CO+CO2 Ice Abundance in Exocomets and Solar System Comets L. Matrà1, M. A. MacGregor2, P. Kalas3,4, M. C. Wyatt1, G. M. Kennedy1, D. J. Wilner2, G. Duchene3,5, A. M. Hughes6, M. Pan7, A. Shannon1,8,9, M. Clampin10, M. P. Fitzgerald11, J. R. Graham3, W. S. Holland12, O. Panić13, and K. Y. L. Su14 1 Institute of Astronomy, University of Cambridge, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0HA, UK; [email protected] 2 Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, 60 Garden Street, Cambridge, MA 02138, USA 3 Astronomy Department, University of California, Berkeley CA 94720-3411, USA 4 SETI Institute, Mountain View, CA 94043, USA 5 Univ. Grenoble Alpes/CNRS, IPAG, F-38000 Grenoble, France 6 Department of Astronomy, Van Vleck Observatory, Wesleyan University, 96 Foss Hill Dr., Middletown, CT 06459, USA 7 MIT Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and