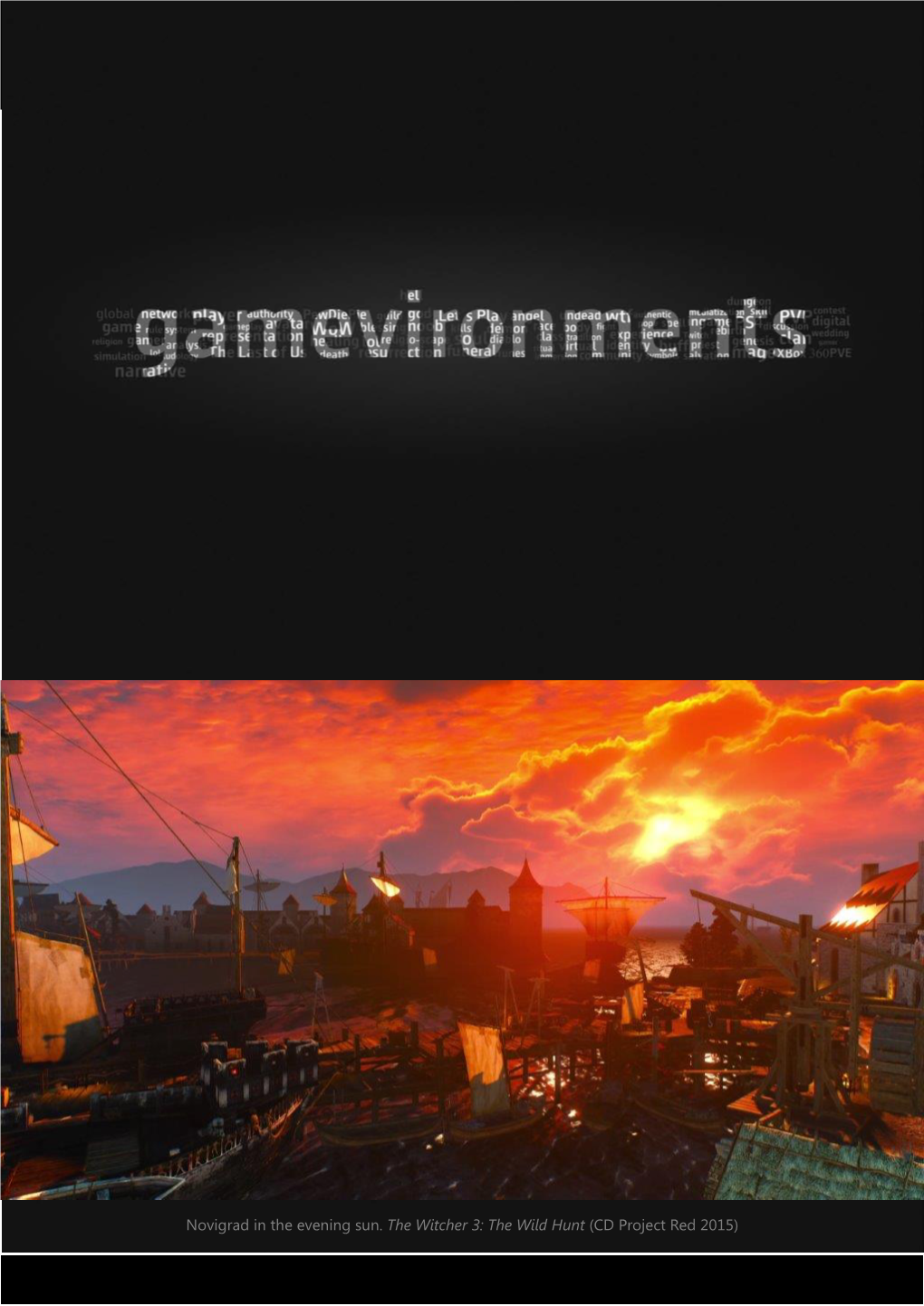

Novigrad in the Evening Sun. the Witcher 3: the Wild Hunt (CD Project Red 2015)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Activision and Lionhead Studios Roll out the Red Carpet at Retail Stores for the Movies (TM): Stunts & Effects Expansion Pack

Activision and Lionhead Studios Roll Out the Red Carpet at Retail Stores for the Movies (TM): Stunts & Effects Expansion Pack SANTA MONICA, June 6, 2006 /PRNewswire-FirstCall via COMTEX News Network/ -- PC gamers can make movie magic with Activision, Inc. (Nasdaq: ATVI) and Lionhead(R) Studios' The Movies(TM): Stunts & Effects Expansion Pack, which ships to retail stores nationwide today. Building on The Movies' critically acclaimed gameplay, The Movies: Stunts & Effects Expansion Pack gives players the tools to turn ordinary scripts into blockbuster films with the addition of stuntmen, astounding visual effects, a variety of dangerous stunts, a movie-making toolset, impressive new sets and an innovative "Freecam Mode" that allows players to adjust the camera location, angle, field of view and path. "The Movies: Stunts & Effects Expansion Pack allows players to create scenes that will have audiences on the edge their seats," said Dusty Welch, vice president of global brand management, Activision, Inc. "From car scenes that end in epic explosions to sci-fi thrillers that feature alien spaceships destroying an entire city, The Movies: Stunts & Effects gives fans what they need to make runaway smash hits." The Movies: Stunts & Effects Expansion Pack allows players to enhance each scene with a variety of options, including death- defying stunts and various particle and visual effects such as fireball explosions, shattering glass, smoke and lasers. Miniature sets, blue screens and green screens add to the spectacular action with dramatic sweeping angles, larger-than-life scale and the illusion of flying across diverse landscapes. Gamers are further immersed into the Hollywood lifestyle as they train and manage stuntmen, as well as compete for industry awards and achievements by uploading their movies to www.themoviesgame.com for the entire world to see. -

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11

2K and Bethesda Softworks Release Legendary Bundles February 11, 2014 8:00 AM ET The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim and BioShock® Infinite; Borderlands® 2 and Dishonored™ bundles deliver supreme quality at an unprecedented price NEW YORK--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Feb. 11, 2014-- 2K and Bethesda Softworks® today announced that four of the most critically-acclaimed video games of their generation – The Elder Scrolls® V: Skyrim, BioShock® Infinite, Borderlands® 2, and Dishonored™ – are now available in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation®3 computer entertainment system, and Windows PC. ● The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim & BioShock Infinite Bundle combines two blockbusters from world-renowned developers Bethesda Game Studios and Irrational Games. ● The Borderlands 2 & Dishonored Bundle combines Gearbox Software’s fan favorite shooter-looter with Arkane Studio’s first- person action breakout hit. Critics agree that Skyrim, BioShock Infinite, Borderlands 2, and Dishonored are four of the most celebrated and influential games of all time. 2K and Bethesda Softworks(R) today announced that four of the most critically- ● Skyrim garnered more than 50 perfect review acclaimed video games of their generation - The Elder Scrolls(R) V: Skyrim, scores and more than 200 awards on its way BioShock(R) Infinite, Borderlands(R) 2, and Dishonored(TM) - are now available to a 94 overall rating**, earning praise from in two all-new bundles* for $29.99 each in North America on the Xbox 360 some of the industry’s most influential and games and entertainment system from Microsoft, PlayStation(R)3 computer respected critics. -

CHARLOTTE EMILY LOUISE ATKINSON GAMEPLAY ARTIST Technical Artist and Asset Creation

CHARLOTTE EMILY LOUISE ATKINSON GAMEPLAY ARTIST Technical Artist and Asset Creation +44 7584 061 091 | [email protected] Portfolio: https://www.artstation.com/artofcatkin LinkedIn: /artofcatkin | Twitter: @ArtofCatkin 1 AAA Title Shipped 1 Year Experience within the Games Industry. 5 Years of experience with 3D Software and Engines. PERSONAL STATMENT I am an enthusiastic technical gameplay artist with a background in environment art. I’ve got grit and determination; as a result, I like a good challenge. I’m polite, organized, and open-minded. I work well under Pressure and meet required deadlines. I enjoy and work well within a team, and capable of working independently. I am able and willing to take on responsibilities and leadership roles. I adapt and learn new skills quickly and adjust to new requirements/ changes with ease. I’ve been in the games industry for over a year, and have a wide range of skills and experiences. I graduated with Frist class BA Hons in Game Art (2016) and Distinction MA in Games Enterprise (2017) from the University of South Wales. I currently Work for the Warner Bros studio: Tt Games as a Junior Gameplay Artist. I am computer literate and have experience with Jira, SVN, and AAA pipelines. I am highly skilled in software packages, such as; 3Ds Max, Maya, ZBrush, Unreal Engine 4, and Photoshop. I have also acquired experience in Marmoset Toolbag 3, Quixel, Illustrator and traditional art forms. CREDITED TITLES EXPERIENCE 2018: LEGO DC Supervillains Nov 2018 - Current: JUNIOR GAMEPLAY ARTIST Tt Games, Knutsford. 2016: Koe I create, rig and animate interactive assets for Puzzles and Quest with in the Game hubs and pre 2016: Tungsten Valkyrie levels. -

Game Developer Index 2012 Swedish Games Industry’S Reports 2013 Table of Contents

GAME DEVELOPER INDEX 2012 SWEDISH GAMES INDUSTRY’S REPORTS 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 WORDLIST 3 PREFACE 4 TURNOVER AND PROFIT 5 NUMBER OF COMPANIES 7 NUMBER OF EMPLOYEES 7 GENDER DISTRIBUTION 7 TURNOVER PER COMPANY 7 EMPLOYEES PER COMPANY 8 BIGGEST PLAYERS 8 DISTRIBUTION PLATFORMS 8 OUTSOURCING/CONSULTING 9 SPECIALISED SUBCONTRACTORS 9 DLC 10 GAME DEVELOPER MAP 11 LOCATION OF COMPANIES 12 YEAR OF REGISTRY 12 GAME SALES 13 AVERAGE REVIEW SCORES 14 REVENUES OF FREE-TO-PLAY 15 EXAMPLE 15 CPM 16 eCPM 16 NEW SERVICES, NEW PIRACY TARGETS 16 VALUE CHAIN 17 DIGITAL MIDDLEMEN 18 OUTLOOK 18 SWEDISH AAA IN TOP SHAPE 19 CONSOLES 20 PUBISHERS 20 GLOBAL 20 CONCLUSION 22 METHODOLOGY 22 Cover: Mad Max (in development), Avalanche Studios 1 | Game Developer Index 2012 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Game Developer Index maps, reports and analyzes the Swedish game devel- opers’ annual operations and international trends by consolidating their respective annual company accounts. Swedish game development is an export industry and operates in a highly globalized market. In just a few decades the Swedish gaming industry has grown from a hobby for enthusiasts into a global industry with cultural and economic importance. The Game Developer Index 2012 compiles Swedish company accounts for the most recently reported fiscal year. The report highlights: • Swedish game developers’ turnover grew by 60 percent to 414 million euro in 2012. A 215% increase from 2010 to 2012. • Most game developer companies (~60 percent) are profitable and the industry reported a combined profit for the fourth consecutive year. • Job creation and employment is up by 30 percent. -

Virtual Pacifism 1

Virtual Pacifism 1 SCREEN PEACE: HOW VIRTUAL PACIFISM AND VIRTUAL NONVIOLENCE CAN IMPACT PEACE EDUCATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF ARTS OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS BY JULIA E. LARGENT DR. ASHLEY DONNELLY – ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2013 Virtual Pacifism 2 Table of Contents Title Page 1 Table of Contents 2 Acknowledgement 3 Abstract 4 Foreword 5 Chapter One: Introduction and Justification 8 Chapter Two: Literature Review 24 Chapter Three: Approach and Gathering of Research 37 Chapter Four: Discussion 45 Chapter Five: Limitations and a Call for Further Research 57 References 61 Appendix A: Video Games and Violence Throughout History 68 Appendix B: Daniel Mullin’s YouTube Videos 74 Appendix C: Juvenile Delinquency between 1965 and 1996 75 Virtual Pacifism 3 Acknowledgement I would like to thank my committee members, Dr. Ashley Donnelly, Professor Nancy Carlson, and Dr. Paul Gestwicki, for countless hours of revision and guidance. I also would like to thank my friends and family who probably grew tired of hearing about video games and pacifism. Lastly, I would like to thank those nonviolent players who inspired this thesis. Without these individuals playing and posting information online, this thesis would not have been possible. Virtual Pacifism 4 Abstract Thesis: Screen Peace: How Virtual Pacifism and Virtual Nonviolence Can Impact Peace Education Student: Julia E. Largent Degree: Master of Arts College: Communication, Information, and Media Date: July 2013 Pages: 76 The following thesis discusses how virtual pacifism can be utilized as a form of activism and discussed within peace education with individuals of all ages in a society saturated with violent media. -

Ubisoft to Co-Publish Oblivion™ on Playstation®3 and Playstation® Portable Systems in Europe and Australia

UBISOFT TO CO-PUBLISH OBLIVION™ ON PLAYSTATION®3 AND PLAYSTATION® PORTABLE SYSTEMS IN EUROPE AND AUSTRALIA Paris, FRANCE – September 28, 2006 – Today Ubisoft, one of the world’s largest video game publishers, announced that it has reached an agreement with Bethesda Softworks® to co-publish the blockbuster role-playing game The Elder Scrolls® IV: Oblivion™ on PLAYSTATION®3 and The Elder Scrolls® Travels: Oblivion™ for PlayStation®Portable (PSP™) systems in Europe and Australia. Developed by Bethesda Games Studios, Oblivion is the latest chapter in the epic and highly successful Elder Scrolls series and utilizes next- generation video game hardware to fully immerse the players into an experience unlike any other. Oblivion is scheduled to ship for the PLAYSTATION®3 European launch in March 2007 and Spring 2007 on PSP®. “We are pleased to partner with Besthesda Softworks to bring this landmark role-playing game to all PlayStation fans,” said Alain Corre EMEA Executive Director. “No doubt that this brand new version will continue the great Oblivion success story” The Elder Scrolls® IV: Oblivion has an average review score of 93.6%1 and has sold over 1.7 million units world-wide since its launch in March 2006. It has become a standard on Windows and the Xbox 360 TM entertainment system thanks to its graphics, outstanding freeform role- playing, and its hundreds of hours worth of gameplay. 1 Source : gamerankings.com About Ubisoft Ubisoft is a leading producer, publisher and distributor of interactive entertainment products worldwide and has grown considerably through its strong and diversified lineup of products and partnerships. -

Mdbt7 04 Opinion.Pdf

IN THE CIRCUIT COURT FOR MONTGOMERY COUNTY, MARYLAND CHRISTOPHER S. WEAVER : : Plaintiff & Counter-Defendant : : vs. : Civil No. 238840 : ZENIMAX MEDIA, INC. : : Defendant & Counter-Plaintiff : : MEMORANDUM OPINION On December 13, 2002, the plaintiff, Christopher Weaver (hereinafter “ Weaver”), filed suit against his former employer ZeniMax Media Technology (hereinafter ZeniMax) in Montgomery County alleging he had been constructively terminated. Weaver asserts he is entitled to receive the One Million Two Hundred Thousand Dollar ($1,200,000.00) severance payment as specified in clause 4.3 of Weaver’s Executive Employment Agreement. The merits of this case have not yet been reached. The matter before this Court currently is a potentially dispositive motion for sanctions filed by the defendant corporation. ZeniMax argues that Weaver should not be allowed access to this forum because of certain egregious conduct which began during his employment and later came to light in the course of discovery. 1 A two-day evidentiary hearing began on April 1, 2004, and continued on May 5, 2004 in connection with the defendant’s motion. Because this is a case of first impression in Maryland, the Court invited the parties to submit supplementary briefings prior to the first hearing date. After considering the evidence submitted in this matter and the papers filed by both sides, the Court finds the plaintiff’s conduct amounts to civil vigilantism and agrees with the defendant that the plaintiff’s actions ought to bar him from accessing this forum. Accordingly, ZeniMax’s Sanctions Seeking Dismissal of the Plaintiff’s First Amended Complaint Due to Discovery Abuses is GRANTED. -

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015

Loot Crate and Bethesda Softworks Announce Fallout® 4 Limited Edition Crate Exclusive Game-Related Collectibles Will Be Available November 2015 LOS ANGELES, CA -- (July 28th, 2015) -- Loot Crate, the monthly geek and gamer subscription service, today announced their partnership today with Bethesda Softworks® to create an exclusive, limited edition Fallout® 4 crate to be released in conjunction with the game’s worldwide launch on November 10, 2015 for the Xbox One, PlayStation® 4 computer entertainment system and PC. Bethesda Softworks exploded hearts everywhere when they officially announced Fallout 4 - the next generation of open-world gaming from the team at Bethesda Game Studios®. Following the game’s official announcement and its world premiere during Bethesda’s E3 Showcase, Bethesda Softworks and Loot Crate are teaming up to curate an official specialty crate full of Fallout goods. “We’re having a lot of fun working with Loot Crate on items for this limited edition crate,” said Pete Hines, VP of Marketing and PR at Bethesda Softworks. “The Fallout universe allows for so many possibilities – and we’re sure fans will be excited about what’s in store.” "We're honored to partner with the much-respected Bethesda and, together, determine what crate items would do justice to both Fallout and its fans," says Matthew Arevalo, co-founder and CXO of Loot Crate. "I'm excited that I can FINALLY tell people about this project, and I can't wait to see how the community reacts!" As is typical for a Loot Crate offering, the contents of the Fallout 4 limited edition crate will remain a mystery until they are delivered in November. -

Backgrounder: AIIDE 07 Invited Speakers

Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence 445 Burgess Drive Menlo Park, CA 94025 (650) 328-3123 www.aaai.org For press inquiries only, contact: Sara Hedberg (206) 232-1657 (office) [email protected] Backgrounder: AIIDE 07 Invited Speakers 1 of 6 AiLive's LiveMove and LiveCombat Wolff Daniel Dobson and John Funge (AiLive Inc.) This talk describes the successfully productization of the state-of-the-art statistical machine learning technology to create LiveMove and LiveCombat. LiveMove is a groundbreaking artificial intelligence product that enables the Wii Remote to learn. Instead of complicated programming, developers need only take a few minutes to train Wii controllers through examples. Nintendo now sublicenses and promotes LiveMove to Wii developers around the world. Our other product, LiveCombat, gives developers and players the power to build AI characters that learn how to behave by observing the actions of human players. AI characters learn in seconds to be trusted companions or deadly foes. The talk will include many anecdotes and observations from lessons learned (often the hard way) along the way. Wolff Daniel Dobson received his PhD in computer science from Northwestern University, specializing in artificial intelligence and intelligent user interfaces. At Visual Concepts Entertainment, he constructed emotional behavior on NBA2K for Dreamcast, and then became colead for artificial intelligence on NBA2K1 (garnering a Metacritic.com score of 93). For the past 5 years he has worked for AiLive Inc., a startup devoted to next-generation artificial intelligence in games. Working as a designer, producer, engineer, and artist Wolff has been instrumental in developing two commercial products, LiveMove and LiveCombat, that bring groundbreaking real-time machine learning technology to the computer entertainment industry. -

ZERO TOLERANCE: Policy on Supporting 1St Party Xbox Games

ZERO TOLERANCE: Policy on Supporting 1st Party Xbox Games FEBRUARY 6, 2009 TRAINING ALERT Target Audience All Xbox Support Agents Introduction This Training Alert is specific to incorrect referral of game issues to game developers and manufacturers. What’s Important Microsoft has received several complaints from our game partners about calls being incorrectly routed to them when the issue should have been resolved by a Microsoft support agent at one of our call centers. This has grown from an annoyance to seriously affecting Microsoft's ability to successfully partner with certain game manufacturers. To respond to this, Microsoft is requesting all call centers to implement a zero tolerance policy on incorrect referrals of Games issues. These must stay within the Microsoft support umbrella through escalations as needed within the call center and on to Microsoft if necessary. Under no circumstances should any T1 support agent, T2 support staff, or supervisor refer a customer with an Xbox game issue back to the game manufacturer, or other external party. If there is any question, escalate the ticket to Microsoft. Please also use the appropriate article First-party game titles include , but are not limited to , the following examples: outlining support • Banjo Kazooie: Nuts & Bolts boundaries and • Fable II definition of 1 st party • Gears of War 2 games. • Halo 3 • Lips VKB Articles: • Scene It? Box Office Smash • Viva Pinata: Trouble In Paradise #910587 First-party game developers include , but are not limited to, the following #917504 examples: • Bungie Studios #910582 • Bizarre Creations • FASA Studios • Rare Studios • Lionhead Studios Again, due to the seriousness of this issue, if any agent fails to adhere to this policy, Microsoft will request that they be permanently removed from the Microsoft account per our policies for other detrimental kinds of actions. -

Download Download

Close Reading Oblivion: Character Believability and Intelligent Personalization in Games Theresa Jean Tanenbaum Jim Bizzocchi University of California, Irvine Simon Fraser University Department of Informatics School of Interactive Arts & Technology [email protected] [email protected] Abstract This paper investigates issues of character believability and intelligent personalization through a reading of the Elder Scrolls: Oblivion. Oblivion’s opening sequence simultaneously trains players in the function of the game, and allows them to customize their character class through the choices and actions they take. Oblivion makes an ambitious attempt at intelligent personalization in the character creation process. Its strategy is to track early gameplay decisions and “stereotype” players into one of 21 possible classes. This approach has two advantages over a less adaptive system. First, it supports the illusion of the gameworld as a real world by embedding the process of character creation within a narrativised gameplay context. Second, the intelligent recommendation system responds to the player’s desire to believe that the game “knows” something about her personality. This leads the players to conceptualize the system as an entity with autonomous, human-like knowledge. This paper considers ways in which Oblivion both succeeds and fails at mapping player behaviour to appropriate class assignments. It does so through the analysis of multiple replayings of the opening sequence, and the application of two theoretical lenses - character believability and intelligent personalization. The paper documents moments where the dialogue between player and game breaks down, and argues for alternative techniques to customize the play experience within the desires of the player. Author Keywords Game design; believable characters; adaptive systems; interactive narrative; close reading Introduction: Reading Critically In Oblivion Oblivion (Bethesda Softworks, 2006) is the fourth “anchor” game in a series of Computer Role- Playing Games (CRPGs) known as The Elder Scrolls. -

Winning in Games

Sector: Technology Dave Novosel September 29 , 20 20 [email protected] Winning In Games ♦ Microsoft (MSFT), although apparently a much better match than Oracle, lost out on the bidding for TikTok. But it may have saved itself some headaches, given the political interference in that situation. After losing that opportunity, the company turned immediately and announced the acquisition of ZeniMax Media, the parent company of Bethesda Softworks. Bethesda develops and publishes video games, including The Elder Scrolls, Doom, and Fallout. The deal expands Microsoft’s game studios from 15 to 23, strengthening its position in the rapidly expanding gaming market. The timing is good as Microsoft is about to launch its eagerly awaited Xbox Series X and Series S in time for the holiday season. In addition, Microsoft bolsters its line-up to attract more users to its Xbox Game Pass. Microsoft is paying $7.5 billion in cash to acquire ZeniMax Media. ZeniMax is privately held, but speculation is that annual revenue was less than $1 billion, implying that EBITDA was less than $300 million. Therefore the deal could be viewed as quite expensive. But Microsoft has such tremendous financial flexibility that it really won’t have much of an impact on the credit profile. The company has close to $14 billion in cash and another $123 billion in short-term investments. In addition, the company generated more than $30 billion of free cash flow in the fiscal year that just ended June 30 th . ♦ Microsoft posted revenue of $143 billion last year, so the acquisition’s financial impact on operations is minimal.