Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics ISSN 2209-0959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GILE Newsletter #97 (E-Version)

Issue #97 October 2015 Tottori, Japan Newsletter of the "Global Issues in Language Education" Special Interest Group (GILE SIG) of the Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT) GLOBAL ISSUES IN LANGUAGE EDUCATION NEWSLETTER 97th Issue celebrating 97 issues and 25 years in print since 1990 Kip A. Cates, Tottori University, Koyama, Tottori City, JAPAN 680-8551 E-mail: [email protected] Check out back issues on our homepage! Website: www.gilesig.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/gilesig.org NEWSLETTER #97 Our autumn 2015 newsletter features: (1) an article by Zelinda Sherlock that takes a critical look at the content, values and assumptions embedded in English textbooks used in schools in Japan, and (2) a set of lively comments from an on-line debate moderated by British ELT expert Ken Wilson on the question of “Should we talk about global issues in the ELT classroom?” This fall marks the 70th anniversary of the founding of the United Nations in 1945. To commemorate this, we include a special section on Teaching about the United Nations which includes a UN quiz for your students as well as a variety of teaching ideas, activities and resources. This issue also includes reports on this spring’s PanSIG conference (in Kobe) and this summer’s national JACET conference (in Kagoshima). We finish off this edition with a list of global issue calendars for the year 2016 plus a round-up of all the latest global education news and information. ♦ E-SUBSCRIPTIONS: After 20 years as a paper newsletter, we now offer electronic subscriptions by e-mail. -

CONFERENCE PROGRAM TH 25 ISSAT INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE RELIABILITY an D QUALITY I N DESIGN LAS VEGAS, NEVADA, U.S.A

www.issatconferences.org The International Society of Science and Applied Technologies Applied and Science of Society International The Sponsor 3, 2019 3, – 1 AUGUST U.S.A. NEVADA, VEGAS, LAS H H INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS INTELLIGENT SCIENCE DATA d an ISSAT INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE INTERNATIONAL ISSAT PROGRAM CONFERENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM TH 25 ISSAT INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE RELIABILITY and QUALITY in DESIGN LAS VEGAS, NEVADA, U.S.A. H AUGUST 1 – 3, 2019 Conference Sponsor In Cooperation with The Korean Reliability Society The International Society of Reliability Engineering Association Science and Applied Technologies of Japan www.issatconferences.org Organizing Committee Members Conference Chairs Hoang Pham Rutgers University, USA Shigeru Yamada Tottori University, Japan Program Chairs Yi-Kuei Lin National Chiao Tung University, Taiwan Feng-Bin Sun Tesla Motors, USA Arrangements Chair Zhenmin Chen Florida International University, USA Program Committee Members Mahmoud Boushaba (Algeria) D. Gary Harlow (USA) Shey-Huei Sheu (Taiwan) Antonio C. Caputo (Italy) Cheng-Fu Huang (Taiwan) Feng-Bin Sun (USA) Philippe Castagliola (France) Shinji Inoue (Japan) Kazuyuki Suzuki (Japan) Antonella Certa (Italy) Mingxiao Jiang (USA) Yoshinobu Tamura (Japan) In Hong Chang (South Korea) Taghi M. Khoshgoftaar (USA) Loon-Ching Tang (Singapore) Ping-Chen Chang (Taiwan) Mitsuhiro Kimura (Japan) Zhigang Tian (Canada) Chung-Ho Chen (Taiwan) Uday Kumar (Sweden) Fugee Tsung (Hong Kong) Shin-Guang Chen (Taiwan) Yi-Kuei Lin (Taiwan) Fl. Popentiu Vladicescu (Romania) Zhenmin Chen (USA) Anatoly Lisnianski (Israel) Nikola Vujanovic (Serbia) Kuan-Jung Chung (Taiwan) N. V. R. Naidu (India) Eric T. T. Wong (Hong Kong) Balbir S. Dhillon (Canada) Dong Ho Park (South Korea) Liyang Xie (China) Elsayed A. -

Japanese Universities That Offer Teacher-Training Programs

Japanese Universities that Offer Teacher-Training Programs Hokkaido University of Education – http://www.hokkyodai.ac.jp Hirosaki University - http://www.hirosaki-u.ac.jp/kokusai/index.html Iwate University – http://iuic.iwate-u.ac.jp/ Miyagi University of Education – http://www.miyakyo-u.ac.jp Fukushima University – http://www.fukushima-u.ac.jp/ Ibaraki University – http://www.ibaraki.ac.jp/ University of Tsukuba – www.kyouiku.tsukuba.ac.jp www.intersc.tsukuba.ac.jp Utsunomiya University – http://www.utsunomiya-u.ac.jp/ Gunma University – http://www.gunma-u.ac.jp Saitama University – http://www.saitama-u.ac.jp Chiba University – http://www.chiba-u.ac.jp Tokyo University of Foreign Studies – http://www.tufs.ac.jp Tokyo Gakugei University – http://www.u-gakugei.ac.jp/ Yokohama National University – http://www.ynu.ac.jp/english/ Niigata University – http://www.niigata-u.ac.jp/ Joetsu University of Education – http://www.juen.ac.jp/ Akita University – http://www.akita-u.ac.jp/english/ Toyama University – http://www.u-toyama.ac.jp Kanazawa University – http://www.kanazawa-u.ac.jp/e/index.html University of Fukui – http://www.u-fukui.ac.jp University of Yamanashi – http://www.yamanashi.ac.jp/ Shinshu University – http://www.shinshu-u.ac.jp/english/index.html Gifu University – https://syllabus.gifu-u.ac.jp/ Shizuoka University – http://www.shizuoka.ac.jp/ Aichi University of Education – http://www.aichi-edu.ac.jp/ http://www.aichi-edu.ac.jp/cie/ 1 Mie University – http://www.mie-u.ac.jp Shiga University – http://www.shiga-u.ac.jp/ -

JAFSA Institutional Member List

Supporting Member(Social Business Partners) 43 ※ Classified by the company's major service [ Premium ](14) Diamond( 4) ★★★★★☆☆ Finance Medical Certificate for Visa Immunization for Studying Abroad Western Union Business Solutions Japan K.K. Hibiya Clinic Global Student Accommodation University management and consulting GSA Star Asia K.K. (Uninest) Waseda University Academic Solutions Corporation Platinum‐Exe( 3) ★★★★★☆ Marketing to American students International Students Support Takuyo Corporation (Lighthouse) Mori Kosan Co., Ltd. (WA.SA.Bi.) Vaccine, Document and Exam for study abroad Tokyo Business Clinic JAFSA Institutional Platinum( 3) ★★★★★ Vaccination & Medical Certificate for Student University management and consulting Member List Shinagawa East Medical Clinic KEI Advanced, Inc. PROGOS - English Speaking Test for Global Leaders PROGOS Inc. Gold( 2) ★★★☆ Silver( 2) ★★★ Institutional number 316!! Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Global Human Resources services・Study Abroad Information Access Nextage Co.,Ltd Doorkel Co.,Ltd. DISCO Inc. Mynavi Corporation [ Standard ](29) (As of July 1, 2021) Standard20( 2) ★☆ Study Abroad Information Housing・Hotel Keibunsha MiniMini Corporation . Standard( 27) ★ Study Abroad Program and Support Insurance / Risk Management /Finance Telecommunication Arc Three International Co. Ltd. Daikou Insurance Agency Kanematsu Communications LTD. Australia Ryugaku Centre E-CALLS Inc. Berkeley House Language Center JAPAN IR&C Corporation Global Human Resources Development Fuyo Educations Co., Ltd. JI Accident & Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. JTB Corp. TIP JAPAN Fourth Valley Concierge Corporation KEIO TRAVEL AGENCY Co.,Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Insurance Co., Ltd. Originator Co.,Ltd. OKC Co., Ltd. Tokio Marine & Nichido Medical Service Co.,Ltd. WORKS Japan, Inc. Ryugaku Journal Inc. Sanki Travel Service Co.,Ltd. Housing・Hotel UK London Study Abroad Support Office / TSA Ltd. -

Graduate School Overview

AY 2019 Graduate School Overview <Reference Only> Osaka City University Table of Contents Page History ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 Enrollment Quotas ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 1 Research Fields and Classes Graduate School of Business ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 2 Graduate School of Economics ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 4 Graduate School of Law ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 5 Graduate School of Literature and Human Sciences ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 7 Graduate School of Science ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 12 Graduate School of Engineering ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 15 Graduate School of Medicine ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 19 Graduate School of Nursing ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 26 Graduate School of Human Life Science ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・28 Graduate School for Creative Cities ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 31 Graduate School of Urban Management ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・32 Degrees ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・34 Entrance Examinations ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・35 Alma Maters of Enrollees ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・ 40 Graduate School Exam Schedule (tentative) ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・42 Directions ・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・・44 History■ History Osaka City University, the foundation of this graduate school, was established using a reform of the Japanese educational system in 1949 as an opportunity to merge the former -

Kobe University Repository : Kernel

Kobe University Repository : Kernel The Last Message of Kazuo Itoga: "Let These Children be the Light of タイトル the World": A Historic Perspective of "Guaranteeing the Right of Title Development to All" 著者 Watanabe, Akio Author(s) 掲載誌・巻号・ページ Journal of Special Education Research,4(1):17-20 Citation 刊行日 2015-08 Issue date 資源タイプ Journal Article / 学術雑誌論文 Resource Type 版区分 publisher Resource Version 権利 ©2015 The Japanese Association of Special Education Rights DOI 10.6033/specialeducation.4.17 JaLCDOI URL http://www.lib.kobe-u.ac.jp/handle_kernel/90003267 PDF issue: 2021-09-26 J. Spec. Educ. Res. 4(1): 17-20 (2015) Special Education in Japan The Last Message of Kazuo Itoga: "Let These Children he the Light of the World": A Historic Perspective of "Guaranteeing the Right of Development to All" Akio WATANABEl • 2. * 1 Emeritus Professor of Tottori University. Japan 2 Professor of Kobe University. Japan Key Words: Kazuo Itoga. centenary year of birth. Ohmi Gakuen. Let These Children be the Light of the World. Guaranteeing the Right of Development to All Introduction soul!" He finally undertook studies in Philosophy, at Kyoto Imperial University in 1935. After his uni In 1946, Kazuo Itoga (1914-68) co-established versity graduation, he worked as a substitute teacher Ohmi Gakuen, an institution for children with spe at an elementary school in Kyoto for a few years. In cial needs. 2014 marked the centenary year of Itoga's the lead-up to World War II, he was exempted from birth, and is the same year in which the Convention military service due to illness, and he instead started on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was ratified work for the Shiga Prefectural Government in-l940. -

The Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension

Hypertension Research (2014) 37, 254–255 & 2014 The Japanese Society of Hypertension All rights reserved 0916-9636/14 www.nature.com/hr The Japanese Society of Hypertension Committee for Guidelines for the Management of Hypertension CHAIRPERSON Kazuaki SHIMAMOTO (Sapporo Medical University) WRITING COMMITTEE Katsuyuki ANDO (University of Tokyo) Ikuo SAITO (Keio University) Toshihiko ISHIMITSU (Dokkyo Medical University) Shigeyuki SAITOH (Sapporo Medical University) Sadayoshi ITO (Tohoku University) Kazuyuki SHIMADA (Jichi Medical University) Masaaki ITO (Mie University) Kazuaki SHIMAMOTO (Sapporo Medical University) Hiroshi ITOH (Keio University) Tatsuo SHIMOSAWA (University of Tokyo) Yutaka IMAI (Tohoku University) Hiromichi SUZUKI (Saitama Medical University) Tsutomu IMAIZUMI (Kurume University) Norio TANAHASHI (Saitama Medical University) Hiroshi IWAO (Osaka City University) Kouichi TAMURA (Yokohama City University) Shinichiro UEDA (University of the Ryukyus) Takuya TSUCHIHASHI (Steel Memorial Yahata Hospital) Makoto UCHIYAMA (Uonuma Kikan Hospital) Mitsuhide NARUSE (NHO Kyoto Medical Center) Satoshi UMEMURA (Yokohama City University) Koichi NODE (Saga University) Yusuke OHYA (University of the Ryukyus) Jitsuo HIGAKI (Ehime University) Katsuhiko KOHARA (Ehime University) Naoyuki HASEBE (Asahikawa Medical College) Hisashi KAI (Kurume University) Toshiro FUJITA (University of Tokyo) Naoki KASHIHARA (Kawasaki Medical School) Masatsugu HORIUCHI (Ehime University) Kazuomi KARIO (Jichi Medical University) Hideo MATSUURA (Saiseikai Kure Hospital) -

[email protected] Participant List (Japan) 2015.1.23 9Th French

Participant list (Japan) 2015.1.23 9th French-Japanese Joint Seminar on Fluorine Chemistry Title/Name Institution/Address e-mail Presentation Title (Tentative) or Key Words Division of Applied Chemistry, Institute of Engineering Synthetic application of 2,3-epoxybutanoates with an Rf group at the 3 1 Prof. Takashi Yamazaki Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology [email protected] Yes position 2-24-16 Nakamachi, Koganei, Tokyo 184-8588 Japan Graduate School of Energy Science Kyoto University 2 Prof. Rika Hagiwara [email protected] Inorganic, Ionic liquid Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan TEL: +81-75-753-5822 Kyoto University 3 Prof. Kazuhiko Matsumoto Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan [email protected] Yes Inorganic, Plastic crystal TEL: +81-75-753-5822 Department of Energy and Hydrocarbon Chemistry Kyoto University 4 Prof. Hiroshi Kageyama [email protected] Yes Inorganic, Solid State Chemistry Nishikyo-ku, Kyoto 615-8530, JAPAN TEL: +81-75-383-2506 Mr. Shinya Tawa Kyoto University 5 (PhD Student, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan No (Inorganic) (Hagiwara Group) TEL: +81-75-753-5822 University of Hyogo 6 Prof. Yoshiaki Matsuo [email protected] Yes Electrochemical fluorination of graphite in hydrofluoric acid 2167 Shosha, Himeji, Hyogo, 671-2280 Japan Univesity of Fukui 7 Prof. Susumu Yonezawa 3-9-1 Bunkyo, 910-8507 Fukui, Japan [email protected] Yes Surface fluorination of 5V class cathode active material for LIB Tel: +81-776-27-9948 Univesity of Fukui 8 Prof. Jae-Ho Kim 3-9-1 Bunkyo, 910-8507 Fukui, Japan [email protected] Yes Surface fluorination of Titania and Its Application Tel: +81-776-27-9948 National Institute for Materials Science (NIMS) 9 Dr. -

GILE Newsletter 77

Issue #77 October 2010 Tottori, Japan Newsletter of the "Global Issues in Language Education" Special Interest Group (GILE SIG) of the Japan Association for Language Teaching (JALT) GLOBAL ISSUES IN LANGUAGE EDUCATION NEWSLETTER 77th Issue celebrating 77 issues and 20 years in print since 1990 Kip A. Cates, Tottori University, Koyama, Tottori City, JAPAN 680-8551 E-mail: [email protected] Work Tel/Fax: 0857-31-5148 Website: www.gilesig.org Check out back issues on our homepage! NEWSLETTER #77 Here’s the fall edition of our Global Issues Newsletter! This year marks our 20th year in print. Check out our two decades of back issues on our website. This issue features (1) a report by Hitomi Sakamoto about a peace education unit on Okinawa, (2) a description by Thomas Lockley of teaching materials he designed about “children around the world” and (3) an article by Warren Decker on international volunteer work for EFL students. We also include a report on this spring’s UK IATEFL conference plus a preview of JALT 2010. GILE is co-sponsoring a Japan lecture tour by Middle East peace activist, Anna Baltzer. Catch her talk at JALT or in your area and support her work by buying her book and DVD. ♦ INVITATION: After 20 years as a paper newsletter, we’re now offering electronic subscriptions by e-mail. Please let us know if you’d like to try this eco-friendly option! Special features this issue: * Abstracts of articles on global themes from language teaching journals 4 * Conference Report: Global Issues at IATEFL 2010 (Harrogate, England) 5 - 8 * Conference Preview: Global Issues at JALT 2010 (Nagoya, Japan) 9 – 10 * Witness in Palestine: Anna Baltzer Japan Lecture Tour (Nov. -

1. Japanese National, Public Or Private Universities

1. Japanese National, Public or Private Universities National Universities Hokkaido University Hokkaido University of Education Muroran Institute of Technology Otaru University of Commerce Obihiro University of Agriculture and Veterinary Medicine Kitami Institute of Technology Hirosaki University Iwate University Tohoku University Miyagi University of Education Akita University Yamagata University Fukushima University Ibaraki University Utsunomiya University Gunma University Saitama University Chiba University The University of Tokyo Tokyo Medical and Dental University Tokyo University of Foreign Studies Tokyo Geijutsu Daigaku (Tokyo University of the Arts) Tokyo Institute of Technology Tokyo University of Marine Science and Technology Ochanomizu University Tokyo Gakugei University Tokyo University of Agriculture and Technology The University of Electro-Communications Hitotsubashi University Yokohama National University Niigata University University of Toyama Kanazawa University University of Fukui University of Yamanashi Shinshu University Gifu University Shizuoka University Nagoya University Nagoya Institute of Technology Aichi University of Education Mie University Shiga University Kyoto University Kyoto University of Education Kyoto Institute of Technology Osaka University Osaka Kyoiku University Kobe University Nara University of Education Nara Women's University Wakayama University Tottori University Shimane University Okayama University Hiroshima University Yamaguchi University The University of Tokushima Kagawa University Ehime -

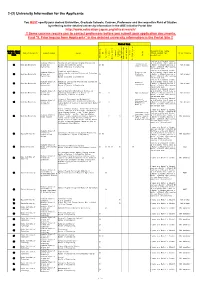

(2) University Information for the Applicants

2-(2) University Information for the Applicants You MUST specify your desired Univrsities, Graduate Schools, Courses, Professors and the respective Field of Studies by referring to the detailed university information in the ABE Initiative Portal Site. http://www.education-japan.org/africa/search/ !! Some courses require you to contact professors before you submit your application documents. Find "9. Prior Inquiry from Applicants" in the detailed university information in the Portal Site !! Field of Study e e c e e n c n c r o g e n / e n a i n r e i e e f c s t i u e m i s c c s i l i s a r t c s c Standard Time Table c Graduate School S r r c e l e r T e l n i i S b e e S n t W m l C e u e r u Code for Third Name of University Graduate School Course i s m h (Years needed for Prior Inquiry o a I n c i u l P s i m t e l n c i i c o a u n o O Batch n a o i g r S T c graduation) / B i C i i c t n g i m r c E i E A d d a o l e A M S o M P Starting as a Research Student Graduate School of Information and Computer Science/International up to 6 months, then 2 years as Information and 1A Doshisha University Science and Science and Technology Course ○ ○ a Master’s Student years as a Not allowed Computer Science Engineering Master of Science in Engineering Master’s Student after passing the entrance exam Starting as a Research Student Electrical and Electronic Graduate School of up to 6 months, then 2 years as Engineering/International Science and Technology Electrical and 1B Doshisha University Science and ○ Electronic a Master’s Student years -

Board Members and Auditors and Supervisors

JSRM 2020-2022 Name Affiliation e-mail Chairperson of the Executive board Yutaka OSUGA Prof./MR. The University of Tokyo/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Vice Chairperson of the Executive board Jo KITAWAKI Prof./MR. Kyoto Prefectural University of Medicine/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Publications Committee Norihiro SUGINO Prof./MR. Yamaguchi University/ obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Koichi NAGAO Prof./MR. Toho University Omori Medical Center/Urology [email protected] Exective Board Members International Relations Osamu ISHIHARA Prof./MR. Saitama Medical University/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Public Relations/Gender Equality Yukiko KATAGIRI Prof./MS. Toho University Omori Medical Center/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Conflict of interest Committee/Glossary Committee Koji KUGU Manager/MR. Tokyo Metropolitan Boktoh Hospital [email protected] Scientific Program Committee Naoaki KUJI Prof./MR. Tokyo Medical University Hospital/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Board Certification Committee Hiroaki SHIBAHARA Prof./MR. Hyogo College of Medicine/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Secretary General Akira TSUJIMURA Prof./MR. Jyuntendo University Urayasu Hospital/Urology [email protected] Social Insurance Committee Yukihiro TERADA Prof./MR. Akita University/obstetrics and gynecology [email protected] Teikyo University School of Medicine University Hospital, Mizonokuchi/ obstetrics Furture Review Committee Osamu NISHII Prof./MR. and gynecology [email protected] Ethics Committee Tasuku HARADA Prof./MR. Tottori University/ Reproductive-Perinatal Medicine and Gynecologic Oncology [email protected] Treasurer Hiroshi FUJIWARA Prof./MR.