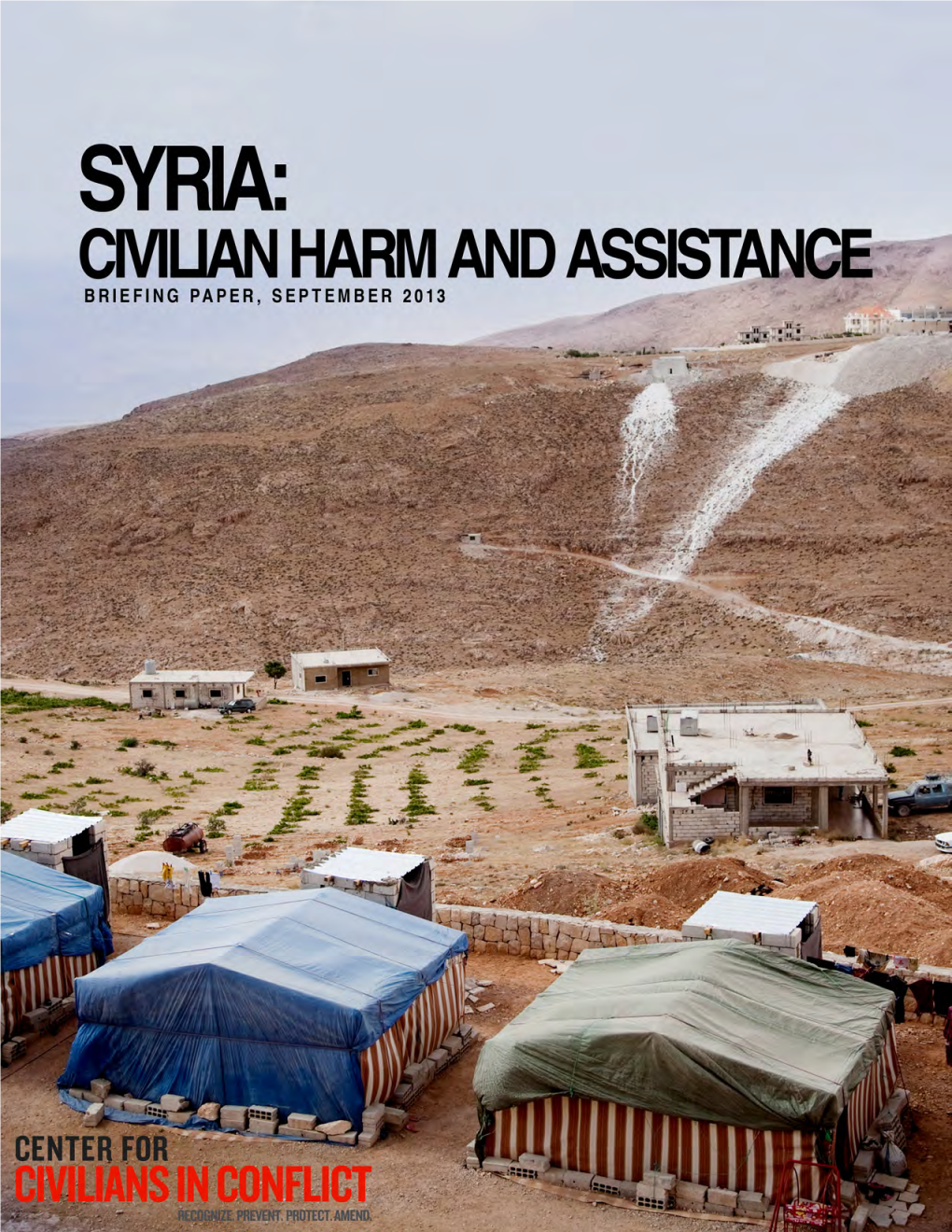

Syria: Civilian Harm and Assistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oral Update of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic

Distr.: General 18 March 2014 Original: English Human Rights Council Twenty-fifth session Agenda item 4 Human rights situations that require the Council’s attention Oral Update of the independent international commission of inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic 1 I. Introduction 1. The harrowing violence in the Syrian Arab Republic has entered its fourth year, with no signs of abating. The lives of over one hundred thousand people have been extinguished. Thousands have been the victims of torture. The indiscriminate and disproportionate shelling and aerial bombardment of civilian-inhabited areas has intensified in the last six months, as has the use of suicide and car bombs. Civilians in besieged areas have been reduced to scavenging. In this conflict’s most recent low, people, including young children, have starved to death. 2. Save for the efforts of humanitarian agencies operating inside Syria and along its borders, the international community has done little but bear witness to the plight of those caught in the maelstrom. Syrians feel abandoned and hopeless. The overwhelming imperative is for the parties, influential states and the international community to work to ensure the protection of civilians. In particular, as set out in Security Council resolution 2139, parties must lift the sieges and allow unimpeded and safe humanitarian access. 3. Compassion does not and should not suffice. A negotiated political solution, which the commission has consistently held to be the only solution to this conflict, must be pursued with renewed vigour both by the parties and by influential states. Among victims, the need for accountability is deeply-rooted in the desire for peace. -

Second Quarterly Report on Besieged Areas in Syria May 2016

Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Colophon ISBN/EAN:9789492487018 NUR 698 PAX serial number: PAX/2016/06 About PAX PAX works with committed citizens and partners to protect civilians against acts of war, to end armed violence, and to build just peace. PAX operates independently of political interests. www.paxforpeace.nl / P.O. Box 19318 / 3501 DH Utrecht, The Netherlands / [email protected] About TSI The Syria Institute (TSI) is an independent, non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in Washington, DC. TSI was founded in 2015 in response to a recognition that today, almost six years into the Syrian conflict, information and understanding gaps continue to hinder effective policymaking and drive public reaction to the unfolding crisis. Our aim is to address these gaps by empowering decision-makers and advancing the public’s understanding of the situation in Syria by producing timely, high quality, accessible, data-driven research, analysis, and policy options. To learn more visit www.syriainstitute.org or contact TSI at [email protected]. Photo cover: Women and children spell out ‘SOS’ during a protest in Daraya on 9 March 2016, (Source: courtesy of Local Council of Daraya City) Siege Watch Second Quarterly Report on besieged areas in Syria May 2016 Table of Contents 4 PAX & TSI ! Siege Watch Acronyms 7 Executive Summary 8 Key Findings and Recommendations 9 1. Introduction 12 Project Outline 14 Challenges 15 General Developments 16 2. Besieged Community Overview 18 Damascus 18 Homs 30 Deir Ezzor 35 Idlib 38 Aleppo 38 3. Conclusions and Recommendations 40 Annex I – Community List & Population Data 46 Index of Maps & Tables Map 1. -

Pdf, 366.38 Kb

FF II CC SS SS Field Information and Coordination Support Section Division of Operational Services Israel Sources: UNHCR, Global Insight digital mapping © 1998 Europa Technologies Ltd. As of December 2009 Israel_Atlas_A3PC.WOR Dahr al Ahmar Jarba The designations employed and the presentation of material on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the 'Aramtah Ma'adamiet Shih Harran al 'Awamid Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, Qatana Haouch Blass 'Artuz territory, city or area of its authorities or concerning the delimitation of its Najha frontiers or boundaries LEBANON Al Kiswah Che'baâ Douaïr Al Khiyam Metulla Sa`sa` ((( Kafr Dunin Misgav 'Am Jubbata al Khashab ((( Qiryat Shemons Chakra Khan ar Rinbah Ghabaqhib Rshaf Timarus Bent Jbail((( Al Qunaytirah Djébab Nahariyya El Harra ((( Dalton An Namir SYRIAN ARAB Jacem Hatzor GOLANGOLAN Abu-Senan GOLANGOLAN Ar Rama Acre ((( Boutaiha REPUBLIC Bi'nah Sahrin Tamra Shahba Tasil Ash Shaykh Miskin ((( Kefar Hittim Bet Haifa ((( ((( ((( Qiryat Motzkin ((( ((( Ibta' Lavi Ash Shajarah Dâail Kafr Kanna As Suwayda Ramah Kafar Kama Husifa Ath Tha'lah((( ((( ((( Masada Al Yadudah Oumm Oualad ((( ((( Saïda 'Afula ((( ((( Dar'a Al Harisah ((( El 'Azziya Irbid ((( Al Qrayyah Pardes Hanna Besan Salkhad ((( ((( ((( Ya'bad ((( Janin Hadera ((( Dibbin Gharbiya El-Ne'aime Tisiyah Imtan Hogla Al Manshiyah ((( ((( Kefar Monash El Aânata Netanya ((( WESTWEST BANKBANK WESTWEST BANKBANKTubas 'Anjara Khirbat ash Shawahid Al Qar'a' -

The Potential for an Assad Statelet in Syria

THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras THE POTENTIAL FOR AN ASSAD STATELET IN SYRIA Nicholas A. Heras policy focus 132 | december 2013 the washington institute for near east policy www.washingtoninstitute.org The opinions expressed in this Policy Focus are those of the author and not necessar- ily those of The Washington Institute for Near East Policy, its Board of Trustees, or its Board of Advisors. MAPS Fig. 1 based on map designed by W.D. Langeraar of Michael Moran & Associates that incorporates data from National Geographic, Esri, DeLorme, NAVTEQ, UNEP- WCMC, USGS, NASA, ESA, METI, NRCAN, GEBCO, NOAA, and iPC. Figs. 2, 3, and 4: detail from The Tourist Atlas of Syria, Syria Ministry of Tourism, Directorate of Tourist Relations, Damascus. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this publica- tion may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. © 2013 by The Washington Institute for Near East Policy The Washington Institute for Near East Policy 1828 L Street NW, Suite 1050 Washington, DC 20036 Cover: Digitally rendered montage incorporating an interior photo of the tomb of Hafez al-Assad and a partial view of the wheel tapestry found in the Sheikh Daher Shrine—a 500-year-old Alawite place of worship situated in an ancient grove of wild oak; both are situated in al-Qurdaha, Syria. Photographs by Andrew Tabler/TWI; design and montage by 1000colors. -

In the Name of the Displaced Afrin People in Shehba to the World Health Organization

الهﻻل اﻷحمر الكردي HEYVA SOR A KURD فرع عفرين ŞAXÊ EFRÎNÊ In the name of the displaced Afrin people in Shehba To the World Health Organization The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), issued a report regarding the emergence of corona virus (COVID-19) in the Syrian Republic on / 11th of March 2020 /, the report stated that the Syrian Ministry of Health confirmed the negative of all cases that were suspected and no one was infected. To counter the threat of the virus, the World Health Organization provides all means of support and assistance to the Syrian Ministry of Health to supplement its ability and preparedness to address this epidemic by providing detection and monitoring equipment, training health personnel in several governorates, and providing quarantine centers in addition to holding workshops aimed at enhancing awareness and understanding the risks of the epidemic. The report stated that the readiness of isolation centers was confirmed in / 6 / areas, namely (Damascus, Aleppo, Deir Al-Zour, Homs, Lattakia and Qamishli) and a health center is currently being established that deals with corona cases in Dwer region in the Damascus countryside. What about more than two hundred thousand displaced people in the northern countryside of Aleppo (Al-Shahba)? Through the report, we see great efforts to help the Syrians ward off the threat of this epidemic, but it is very clear that they forgot a very large geographical spot in which thousands of displaced people are present, and whose presence has reached two years, amid great disregard from the World Health Organization and the Syrian government as well. -

Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012

United Nations S/2012/550 Security Council Distr.: General 8 November 2012 Original: English Identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council Upon instructions from my Government, and following my letters dated 16 to 20 and 23 to 25 April, 7, 11, 14 to 16, 18, 21, 24, 29 and 31 May, 1, 4, 6, 7, 11, 19, 20, 25, 27 and 28 June, and 2, 3, 9 and 11 July 2012, I have the honour to attach herewith a detailed list of violations of cessation of violence that were committed by armed groups in Syria on 9 July 2012 (see annex). It would be highly appreciated if the present letter and its annex could be circulated as a document of the Security Council. (Signed) Bashar Ja’afari Ambassador Permanent Representative 12-58099 (E) 271112 281112 *1258099* S/2012/550 Annex to the identical letters dated 13 July 2012 from the Permanent Representative of the Syrian Arab Republic to the United Nations addressed to the Secretary-General and the President of the Security Council [Original: Arabic] Monday, 9 July 2012 Rif Dimashq governorate 1. At 2200 hours on it July 2012, an armed terrorist group abducted Chief Warrant Officer Rajab Ballul in Sahnaya and seized a Government vehicle, licence plate No. 734818. 2. At 0330 hours, an armed terrorist group opened fire on the law enforcement checkpoint of Shaykh Ali, wounding two officers. 3. At 0700 hours, an armed terrorist group detonated an explosive device as a law enforcement overnight bus was passing the Artuz Judaydat al-Fadl turn-off on the Damascus-Qunaytirah road, wounding three officers. -

Irbid Development Area

Where to Invest? Jordan’s Enabling Platforms Elias Farraj Advisor to the CEO Jordan Investment Board Enabling Platforms A. Development Areas and Zones . King Hussein Business Park (KHBP) . King Hussein Bin Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) . Irbid Development Area . Ma’an Development Area (MDA) B. Aqaba Special Economic Zone C. Qualified Industrial Zones (QIZ) D. Industrial Estates E. Free Zones Development Area Law • The Government of Jordan Under the Development Areas Law (GOJ) enacted new Income Tax[1] 5% On all taxable income from Development Areas Law in activities within the Area 2008 that provides a clear Sales Tax 0% On goods sold into (or indicator of the within) the Development Area for use in economic Government’s commitment activities to the success of Import Duties 0% On all materials, instruments, development zones. machines, etc to be used in establishing, constructing and equipping an enterprise • This law aims to provides in the Area further streamlining and Social Services Tax 0% On all income accrued within enhance quality-of-service the Area or outside the in the delivery of licensing, Kingdom Dividends Tax 0% On all income accrued within permits and the ongoing the Area or outside the procedures necessary for the Kingdom operations of site manufacturers and 1 No income tax on profits from exports exporters. Areas Under the Development Areas Law Irbid Development King Hussein Bin Area (IDA) Talal Development Area KHBTDA (Mafraq) ICT, Healthcare Middle & Back Offices, and Research and Industrial Production, Development. -

Salvaging Syria's Economy

Research Paper David Butter Middle East and North Africa Programme | March 2016 Salvaging Syria’s Economy Contents Summary 2 Introduction 3 Institutional Survival 6 Government Reach 11 Resource Depletion 14 Property Rights and Finance 22 Prospects: Dependency and Decentralization 24 About the Author 27 Acknowledgments 27 1 | Chatham House Salvaging Syria’s Economy Summary • Economic activity under the continuing conflict conditions in Syria has been reduced to the imperatives of survival. The central government remains the most important state-like actor, paying salaries and pensions to an estimated 2 million people, but most Syrians depend in some measure on aid and the war economy. • In the continued absence of a political solution to the conflict, ensuring that refugees and people in need within Syria are given adequate humanitarian support, including education, training and possibilities of employment, should be the priority for the international community. • The majority of Syrians still living in the country reside in areas under the control of President Bashar al-Assad’s regime, which means that a significant portion of donor assistance goes through Damascus channels. • Similarly, any meaningful post-conflict reconstruction programme will need to involve considerable external financial support to the Syrian government. Some of this could be forthcoming from Iran, Russia, the UN and, perhaps, China; but, for a genuine economic recovery to take hold, Western and Arab aid will be essential. While this provides leverage, the military intervention of Russia and the reluctance of Western powers to challenge Assad mean that his regime remains in a strong position to dictate terms for any reconstruction programme. -

Highlights Situation Overview

Syria Crisis Bi-Weekly Situation Report No. 05 (as of 22 May 2016) This report is produced by the OCHA Syria Crisis offices in Syria, Turkey and Jordan. It covers the period from 7-22 May 2016. The next report will be issued in the second week of June. Highlights Rising prices of fuel and basic food items impacting upon health and nutritional status of Syrians in several governorates Children and youth continue to suffer disproportionately on frontlines Five inter-agency convoys reach over 50,000 people in hard-to-reach and besieged areas of Damascus, Rural Damascus and Homs Seven cross-border consignments delivered from Turkey with aid for 631,150 people in northern Syria Millions of people continued to be reached from inside Syria through the regular programme Heightened fighting displaces thousands in Ar- Raqqa and Ghouta Resumed airstrikes on Dar’a prompting displacement 13.5 M 13.5 M 6.5 M 4.8 M People in Need Targeted for assistance Internally displaced Refugees in neighbouring countries Situation Overview The reporting period was characterised by evolving security and conflict dynamics which have had largely negative implications for the protection of civilian populations and humanitarian access within locations across the country. Despite reaffirmation of a commitment to the country-wide cessation of hostilities agreement in Aleppo, and a brief reduction in fighting witnessed in Aleppo city, civilians continued to be exposed to both indiscriminate attacks and deprivation as parties to the conflict blocked access routes to Aleppo city and between cities and residential areas throughout northern governorates. Consequently, prices for fuel, essential food items and water surged in several locations as supply was threatened and production became non-viable, with implications for both food and water security of affected populations. -

Council Implementing Regulation (EU) 2020/1649

6.11.2020 EN Offi cial Jour nal of the European Union L 370 I/7 COUNCIL IMPLEMENTING REGULATION (EU) 2020/1649 of 6 November 2020 implementing Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria THE COUNCIL OF THE EUROPEAN UNION, Having regard to the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, Having regard to Council Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 of 18 January 2012 concerning restrictive measures in view of the situation in Syria and repealing Regulation (EU) No 442/2011 (1), and in particular Article 32(1) thereof, Having regard to the proposal from the High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Whereas: (1) On 18 January 2012, the Council adopted Regulation (EU) No 36/2012. (2) In view of the gravity of the situation in Syria, and considering the recent ministerial appointments, eight persons should be added to the list of natural and legal persons, entities or bodies subject to restrictive measures in Annex II to Regulation (EU) No 36/2012. (3) Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 should therefore be amended accordingly, HAS ADOPTED THIS REGULATION: Article 1 Annex II to Regulation (EU) No 36/2012 is amended as set out in the Annex to this Regulation. Article 2 This Regulation shall enter into force on the date of its publication in the Official Journal of the European Union. This Regulation shall be binding in its entirety and directly applicable in all Member States. Done at Brussels, 6 November 2020. For the Council The President M. -

Syria Drought Response Plan

SYRIA DROUGHT RESPONSE PLAN A Syrian farmer shows a photo of his tomato-producing field before the drought (June 2009) (Photo Paolo Scaliaroma, WFP / Surendra Beniwal, FAO) UNITED NATIONS SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC - Reference Map Elbistan Silvan Siirt Diyarbakir Batman Adiyaman Sivarek Kahramanmaras Kozan Kadirli TURKEY Viransehir Mardin Sanliurfa Kiziltepe Nusaybin Dayrik Zakhu Osmaniye Ceyhan Gaziantep Adana Al Qamishli Nizip Tarsus Dortyol Midan Ikbis Yahacik Kilis Tall Tamir AL HASAKAH Iskenderun A'zaz Manbij Saluq Afrin Mare Al Hasakah Tall 'Afar Reyhanli Aleppo Al Bab Sinjar Antioch Dayr Hafir Buhayrat AR RAQQA As Safirah al Asad Idlib Ar Raqqah Ash Shaddadah ALEPPO Hamrat Ariha r bu AAbubu a add D Duhuruhur Madinat a LATAKIA IDLIB Ath Thawrah h Resafa K l Ma'arat a Haffe r Ann Nu'man h Latakia a Jableh Dayr az Zawr N El Aatabe Baniyas Hama HAMA Busayrah a e S As Saiamiyah TARTU S Masyaf n DAYR AZ ZAWR a e n Ta rtus Safita a Dablan r r e Tall Kalakh t Homs i Al Hamidiyah d Tadmur E e uphrates Anah M (Palmyra) Tripoli Al Qusayr Abu Kamal Sadad Al Qa’im HOMS LEBANON Al Qaryatayn Hadithah BEYRUT An Nabk Duma Dumayr DAMASCUS Tyre DAMASCUS QQuneitrauneitra Ar Rutbah QUNEITRA Haifa Tiberias AS SUWAIDA IRAQ DAR’A Trebil ISRAELI S R A E L DDarar'a As Suwayda Irbid Jenin Mahattat al Jufur Jarash Nabulus Al Mafraq West JORDAN Bank AMMAN JERUSALEM Bayt Lahm Madaba SAUDI ARABIA Legend Elevation (meters) National capital 5,000 and above First administrative level capital 4,000 - 5,000 Populated place 3,000 - 4,000 International boundary 2,500 - 3,000 First administrative level boundary 2,000 - 2,500 1,500 - 2,000 050100150 1,000 - 1,500 800 - 1,000 km 600 - 800 Disclaimers: The designations employed and the presentation of material 400 - 600 on this map do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal 200 - 400 status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. -

Exhibition Checklist I. Creating Palmyra's Legacy

EXHIBITION CHECKLIST 1. Caravan en route to Palmyra, anonymous artist after Louis-François Cassas, ca. 1799. Proof-plate etching. 15.5 x 27.3 in. (29.2 x 39.5 cm). The Getty Research Institute, 840011 I. CREATING PALMYRA'S LEGACY Louis-François Cassas Artist and Architect 2. Colonnade Street with Temple of Bel in background, Georges Malbeste and Robert Daudet after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 16.9 x 36.6 in. (43 x 93 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 58. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 1 3. Architectural ornament from Palmyra tomb, Jean-Baptiste Réville and M. A. Benoist after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 18.3 x 11.8 in. (28.5 x 45 cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 137. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 4. Louis-François Cassas sketching outside of Homs before his journey to Palmyra (detail), Simon-Charles Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41cm). From Voyage pittoresque de la Syrie, de la Phoénicie, de la Palestine, et de la Basse Egypte (Paris, ca. 1799), vol. 1, pl. 20. The Getty Research Institute, 840011 5. Louis-François Cassas presenting gifts to Bedouin sheikhs, Simon Charles-Miger after Louis-François Cassas. Etching. Plate mark: 8.4 x 16.1 in. (21.5 x 41 cm).