Eucharistic Transformation. Thomas Aquinas' Adoro Te Devote

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CORPUS CHRISTI June 23, 2019 ‘Peace of the Lord Be with You’ Order of Mass

SAINT ADELAIDE PARISH 708 Lowell Street Peabody, MA 01960 Father Raymond Van De Moortell ~ Father David Lewis Ad Majorem Dei Gloriam ~ For the Greater Glory of God CORPUS CHRISTI June 23, 2019 ‘Peace of the Lord Be With You’ Order of Mass MOST HOLY BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST Saturday, June 22, 2019, 4:00 p.m. Sunday, June 23, 2019, 8:30 a.m. & 10:00 a.m. 12:00 Latin Mass, see separate sheet The items in bold print may be found in the blue St. Michael Hymnal. INTRODUCTORY RITES The LORD has sworn, and he will not repent: “You are a priest forever, according to the order PRELUDE: Adoro Te Devote Fedak of Melchizedek.” HYMN: “O Living Bread from Heaven” 670 SECOND READING 1 Corinthians 11:23-26 PENITENTIAL ACT: (“I confess…”) page 15 Brothers and sisters: I received from the Lord KYRIE: “Mass of the Sacred Heart” 141 what I also handed on to you, that the Lord Je- sus, on the night he was handed over, took GLORIA: Roman Missal Chant 125 bread, and, after he had given thanks, broke it COLLECT and said, “This is my body that is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way O God, who in this wonderful Sacrament have also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is left us a memorial of your Passion, grant us, we the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as of- pray, so to revere the sacred mysteries of your ten as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” Body and Blood that we may always experience For as often as you eat this bread and drink the in ourselves the fruits of your redemption. -

Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ St

Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ St. Michael Church June 14, 2020 Prelude Music By Our Love Tom Kendzia Gathering Hymn At the Table of Jesus SIMPLE GIFTS Refrain At the table of Jesus we are nourished and fed By the blessing cup and heaven’s living bread. At the table of Jesus earth and heaven are wed. To a hungry world, by our God we are led. 1. Where love and charity are found, there God is among us; God’s goodness abounds. As Christ gathers many as one, let our hearts be glad and reflect God’s love. 2. Now, as we gather all as one, division is ended, communion begun. Let fear, anger, hatred now end. Let us dwell in love as our God intends. Text: Based on Ubi Caritas; Tony E. Alonso, b. 1980 Tune: SIMPLE GIFTS, Irregular with refrain; Joseph Brackett, Jr., 1797-1882; arr. by Marty Haugen © 2010, GIA Publications, Inc. Sign of the Cross/Greeting Penitential Act Gloria Mass for a New World Haas Opening Prayer First Reading Deuteronomy 8:2-3, 14b-16a Responsorial Psalm O praise the Lord, Jerusalem. Guimont Second Reading 1 Corinthians 10:16-17 Gospel Acclamation Mass for a New World Haas Gospel Reading John 6:51-58 Homily Profession of Faith Nicene Creed I believe in one God, the Father almighty, maker of heaven and earth, of all things visible and invisible. I believe in one Lord Jesus Christ, the Only Begotten Son of God, born of the Father before all ages. God from God, Light from Light, true God from true God, begotten, not made, consubstantial with the Father; through him all things were made. -

Parish of Holy Rosary

Parish of Holy Rosary The Most Holy Body and Blood of Christ (Corpus Christi) th 14 June 2020 Sunday Cycle A Psalter Week 3 Ordinary Time Week 11 Scripture Readings First Reading Deuteronomy 8: 2-3, 14-16 Psalm Psalm 147: 12-15, 19-20 Second Reading 1 Corinthians 10: 16-17 Gospel John 6: 51-58 Reflections for Corpus Christi Pope Francis recalled that the month of June is "The presence of Christ’s true body dedicated in a special way to the Heart of Christ. He and blood in this sacrament cannot said, it is “a devotion that unites the great spiritual be detected by the senses or by teachers and the simple among the people of God.” reason, but by faith alone, which rests upon Divine authority. Hence, Indeed, he continued, “the human and divine Heart of Jesus is the wellspring where we can always draw on Luke 22:19 ("This is my body upon God’s mercy, forgiveness and tenderness. We that shall be delivered up for you"), can do so by focusing on a passage from the Gospel, Cyril says, “Do not doubt whether feeling that at the centre of every gesture, of every this is true, but take rather the word of Jesus there is love, the love of the Father.” Saviour’s words on trust, because We can also do so, Pope Francis said, “by adoring the being the Truth, he does not lie.” Eucharist, where this love is present in the Sacrament. Then our heart too, little by little, will become more St. -

The Cathedral of Saint Paul Birmingham, Alabama

THE CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL BIRMINGHAM, ALABAMA THE MOST HOLY BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST JUNE 7, 2015 Welcome to the Cathedral of Saint Paul. The order of Mass can be found on page 3 in the Sunday’s Word booklets found in the pew racks or on the pew cards. Please follow this order of worship for today’s music. PRELUDE PRELUDE AND VARIATIONS ON “ADORO TE DEVOTE” GERALD NEAR ENTRANCE HYMN AT THAT FIRST EUCHARIST UNDE ET MEMORES ENTRANCE ANTIPHON (8:30 & 11:00AM) Cibavit eos PSALM 81:17 He fed them with the finest wheat and satisfied them with honey from the rock. KYRIE (5:00PM & 11:00AM) MASS VIII KYRIE (8:30AM) MASS Á 4 (BYRD) GLORIA MASS VIII THE LITURGY OF THE WORD The Mass readings can be found on page 105 of Sunday’s Word. FIRST READING EXODUS 24:3-8 RESPONSORIAL PSALM PSALM 116:12-13, 15-16, 17-18 Music: John Schiavone, © OCP Publications, Inc. SECOND READING HEBREWS 9:11-15 SEQUENCE (8:30 & 11:00AM) LAUDA SION Please join in singing the bolded verses of the sequence along with the cantor. ALLELUIA I am the living bread that came down from heaven, says the Lord; whoever eats this bread will live forever. GOSPEL MARK 14:12-16, 22-26 LITURGY OF THE EUCHARIST Page 7 in Sunday’s Word OFFERTORY O FOOD OF EXILES LOWLY INNSBRUCK OFFERTORY MOTET (8:30AM) O SACRUM CONVIVIUM GIOVANNI CROCE O sacrum convivium! in quo Christus sumitur: recolitur memoria passionis eius: mens impletur gratia: et futurae gloriae nobis pignus datur. -

Adoro Te Devote

Adoro Te Devote Eucharistic Adoration in the Spirit of St Thomas Aquinas St Saviour’s Church, Dominick St (D1) Some of the best loved Eucharistic hymns - Adoro Te Devote, Tantum Ergo, Panis Angelicus - were written by one man, the Dominican Friar St. Thomas Aquinas. The Dominican Friars of St. Saviour's Priory, which has been in existence for nearly 800 years, will mark the 50th International Eucharistic Congress by inviting renowned preachers to explain the rich delights of these Eucharistic hymns, all in the presence of the Blessed Sacrament, exposed for our veneration. The preachers include Wojciech Giertych OP, the Pope's personal theologian; Paul Murray OP, a celebrated spiritual writer; John Harris OP, well-known for his ministry to young people; and Terence Crotty OP, a Scripture scholar. The evening events will also include music and silent adoration, and will conclude with the Office of Compline, sung by the Dominican community, and the ancient tradition of the Salve Regina procession. Finally, on Saturday, St Saviour's will host a day-long festival of Eucharistic adoration. Come and join us, as we contemplate the source and summit of our faith, 'in which Christ is received, the memory of His Passion is renewed, the soul is filled with grace, and the pledge of future glory is given to us' (St Thomas Aquinas). Mon 11 June, 8pm Fri 15 June, 8pm Wojciech Giertych OP (Papal Theologian) John Harris OP Pange Lingua Verbum Supernum Prodiens Sat 16 June, 11am-6pm Tues 12 June, 8pm Eucharistic Adoration in St Saviour's Church Paul Murray OP (Professor of Spiritual Theology, Angelicum) Adoro Te Devote Thurs 14 June, 8pm Terence Crotty OP Lauda Sion . -

8 Sessions About EUCHARISTIC SAINTS Contents

8 Sessions about EUCHARISTIC SAINTS Contents St Alphonsus ...............................................................................................................................................................2 St Irenaeus ............................................................................................................................................................... 15 St John Neumann .................................................................................................................................................... 28 St Juliana .................................................................................................................................................................. 35 St Katharine Drexel .................................................................................................................................................. 41 Pope Saint Paul VI .................................................................................................................................................... 51 St Peter Julian Eymard ............................................................................................................................................. 59 St Thomas Aquinas .................................................................................................................................................. 69 1 The Year of the Eucharist St Alphonsus Event Saint Alphonsus Event Category Saint Brief Description of Event To introduce Saint Alphonsus and -

Adoration by Candlelight Oct 26.Pdf

Prelude: Soleil du Soir (In Manus Tuas Domine) – Jean Langlais (1907 – 1991) Procession – Adoro Te Devote 1. Godhead here in hiding, whom I do 3. Bring the tender tale true of the adore,Masked by these bare shadows, Pelican;Bathe me, Jesu Lord, in what shape and nothing more,See, Lord, at Thy bosom ranBlood whereof a single Thy service low lies here a heartLost, all drop has power to winAll the world lost in wonder at the God thou art. forgiveness of its world of sin. 2. Seeing, touching, tasting are in thee 4. Jesu, whom I look at shrouded here deceived:How says trusty hearing? that below,I beseech thee send me what I shall be believed;What God's Son has thirst for so,Some day to gaze on thee told me, take for truth I do;Truth face to face in lightAnd be blest for Himself speaks truly or there's nothing ever with Thy glory's sight. Amen. true. O Salutaris Hostia – Edward Elgar (1857 – 1934) O salutaris Hostia O Saving Victim opening wide Quae coeli pandis ostium. The gate of heaven to all below. Bella premunt hostilia; Our foes press on from every side; Da robur, fer auxilium. Thine aid supply, Thy strength bestow. Uni trinoque Domino To Thy great name be endless praise Sit sempiterna gloria: Immortal Godhead, One in Three; Qui vitam sine termino, Oh, grant us endless length of days, Nobis donet in patria. In our true native land with Thee. Amen. Amen. Mt 3: 13-17 Then Jesus came from Galilee to John at the Jordan to be baptized by him. -

Adoro Te Devote St Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274)

Hymn Communion Adoro te devote St Thomas Aquinas (1225 – 1274) 1. Adoro te devote, latens Deitas, I devoutly adore You, O hidden Deity, Quæ sub his figuris vere latitas; Truly hidden beneath these appearances. Tibi se cor meum totum subjicit, My whole heart submits to You, Quia te contemplans totum deficit. And in contemplating You, it surrenders itself completely. 2. Visus, tactus, gustus in te fallitur, Sight, touch, taste are all deceived in their judgment of You, Sed auditu solo tuto creditur. But hearing suffices firmly to believe. Credo quidquid dixit Dei Filius; I believe all that the Son of God has spoken; Nil hoc verbo veritátis verius. There is nothing truer than this word of truth. 3. In cruce latebat sola Deitas, On the cross only the divinity was hidden, At hic latet simul et Humanitas, But here the humanity is also hidden. Ambo tamen credens atque confitens, Yet believing and confessing both, Peto quod petivit latro pœnitens. I ask for what the repentant thief asked. 4. Plagas, sicut Thomas, non intueor: I do not see the wounds as Thomas did, Deum tamen meum te confiteor. But I confess that You are my God. Fac me tibi semper magis credere, Make me believe more and more in You, In te spem habere, te diligere. Hope in You, and love You. 5. O memoriale mortis Domini! O memorial of our Lord's death! Panis vivus, vitam præstans homini! Living bread that gives life to man, Præsta meæ menti de te vívere, Grant my soul to live on You, Et te illi semper dulce sapere. -

The Thirteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time

THE THIRTEENTH SUNDA Y IN ORDINARY TIME C e l e b r a n t s Reverend William Lloyd Rooney, Junior Diocese of Austin AND THE FIRST MASS OF THANKSGIVING Very Reverend James Misko OF REVEREND Vicar General, Diocese of Austin WILLIAM LLOYD ROONEY, JUNIOR Very Reverend Albert Laforet, Junior Pastor, Saint Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church Reverend Chase Goodman Diocese of Victoria Reverend Jeremy Trull Diocese of Lubbock D e a c o n s Deacon Frank Ashley Deacon Dave Mayes Deacon of the Word Deacon of the Altar S e r v e r s Isaiah Minke Chris Haberberger Michael Robles Daniel Mani Kingsly Ohaeri Antonio Aviles Phillip Gaynor Matthew Krusleski Spencer Hauswirth Blaise Rother Sunday, the Twenty-Eighth of June Two Thousand and Twenty L e c t o r s Eleven o’clock in the Morning Matthew Jewell Jorge Nunez Saint Thomas Aquinas Catholic Church College Station, Texas Introductory Rite Dear family and friends, Thank you for being here today as I celebrate this first Mass of Thanksgiving after ordination to the INTROIT Omnes gentes plaudite manibus (Psalm 46) Priesthood. I give thanks to almighty God for your support over my lifetime. Whether I’ve known you all my life or only a short time, you have had a part in my formation as a priest. Please keep praying for me O clap your hands, all ye nations: shout unto God with the voice of Joy. and all those ordained to the priesthood. For the Lord is high, terrible: a great king over all the earth. -

Eric Choate Three Hymns of St. Thomas Aquinas

T h r e e H y m n s o f S t . T h o m a s A q u i n a s e r i c c h o a t e to Mr. Benjamin Bachmann Adoro Te Devote Text: St. Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274) Eric Choate (b.1990) Adoro te devote, latens Deitas, Prostrate I adore Thee, Deity unseen, Quæ sub his figuris vere latitas; Who Thy glory hidest 'neath these shadows mean; Tibi se cor meum totum subjicit, Lo, to Thee surrendered, my whole heart is bowed, Quia te contemplans totum deficit. Tranced as it beholds Thee, shrined within the cloud. O memoriale mortis Domini! O memorial wondrous of the Lord's own death; Panis vivus, vitam præstans homini! Living Bread, that giveth all Thy creatures breath, Præsta meæ menti de te vívere, Grant my spirit ever by Thy life may live, Et te illi semper dulce sapere. To my taste Thy sweetness never-failing give. Pie Pelicane, Jesu Domine, Pelican of mercy, Jesus, Lord and God, Me immundum munda tuo sanguine: Cleanse me, wretched sinner, in Thy Precious Blood: Cujus una stilla salvum facere Blood where one drop for human-kind outpoured Totum mundum quit ab omni scelere. Might from all transgression have the world restored. Jesu, quem velatum nunc aspicio, Jesus, whom now veiled, I by faith descry, Oro, fiat illud quod tam sitio: What my soul doth thirst for, do not, Lord, deny, Ut te revelata cernens facie, That thy face unveiled, I at last may see, Visu sim beátus tuæ gloriæ. -

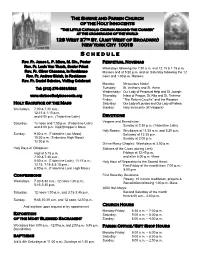

Schedule Rev

The Shrine and Parish Church of the Holy Innocents “The Little Catholic Church Around the Corner” at the crossroads of the world 128 West 37th St. (Just West of Broadway) New York City 10018 Founded 1866 Schedule Rev. Fr. James L. P. Miara, M. Div., Pastor Perpetual Novenas Rev. Fr. Louis Van Thanh, Senior Priest Weekdays following the 7:30 a.m. and 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. Rev. Fr. Oliver Chanama, In Residence Masses and at 5:50 p.m. and on Saturday following the 12 Rev. Fr. Andrew Bielak, In Residence noon and 1:00 p.m. Masses. Rev. Fr. Daniel Sabatos, Visiting Celebrant Monday: Miraculous Medal Tel: (212) 279-5861/5862 Tuesday: St. Anthony and St. Anne Wednesday: Our Lady of Perpetual Help and St. Joseph www.shrineofholyinnocents.org Thursday: Infant of Prague, St. Rita and St. Thérèse Friday: “The Return Crucifix” and the Passion Holy Sacrifice of the Mass Saturday: Our Lady of Lourdes and Our Lady of Fatima Sunday: Holy Innocents (at Vespers) Weekdays: 7:00 & 7:30 a.m.; 12:15 & 1:15 p.m. and 6:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Devotions Vespers and Benediction: Saturday: 12 noon and 1:00 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) Sunday at 2:30 p.m. (Tridentine Latin) and 4:00 p.m. Vigil/Shopper’s Mass Holy Rosary: Weekdays at 11:55 a.m. and 5:20 p.m. Sunday: 9:00 a.m. (Tridentine Low Mass), Saturday at 12:35 p.m. 10:30 a.m. (Tridentine High Mass), Sunday at 2:00 p.m. -

Christ | June 14, 2020

THE SOLEMNITY OF THE MOST HOLY BODY & BLOOD OF CHRIST | JUNE 14, 2020 CATHEDRAL OF SAINT PAUL NATIONAL SHRINE OF THE APOSTLE PAUL 239 Selby Avenue, Saint Paul, Minnesota 55102 651.228.1766 | www.cathedralsaintpaul.org Rev. John L. Ubel, Rector Priests In Residence: Rev. Mark Pavlak & Rev. Joseph Bambenek Deacons Phil Stewart, Ron Schmitz & Nao Kao Yang ARCHDIOCESE OF SAINT PAUL AND MINNEAPOLIS Most Rev. Bernard A. Hebda, Archbishop Most Rev. Andrew H. Cozzens, Auxiliary Bishop LITURGY GUIDE FOR THE SOLEMNITY OF THE MOST HOLY BODY AND BLOOD OF CHRIST PRELUDE (5:15 p.m.) Lawrence W. Lawyer, organ its parched and waterless ground; who brought forth water for you Hymne «Pange lingua» en taillle à 4 Nicolas de Grigny from the flinty rock and fed you in the desert with manna, a food (10:00 a.m., 12:00 p.m., 5:00 p.m.) Dr. Christopher Ganza, organ unknown to your fathers." Allein Gott in dir Höh sei Ehr, BWV 662 & 664 J. S. Bach RESPONSORIAL PSALM Cantor or Lector alone INTROIT Civabit eos Gregorian Missal, Mode II Psalm 147:12-13, 14-15, 19-20 Praise the Lord, Jerusalem. Civábit eos ex ádipe fruménti, allelúia: et de petra, melle saturávit eos, allelúia, Glorify the LORD , O Jerusalem; allelúia, allelúia. Ps. Exsultáte Deo adiutóri nostro: iubiláte Deo Iacob. praise your God, O Zion. He fed them with the finest of wheat, alleluia; and with honey from the rock For he has strengthened the bars of your gates; he satisfied them, alleluia, alleluia. ℣. Rejoice in honor of God our helper; shout he has blessed your children within you.