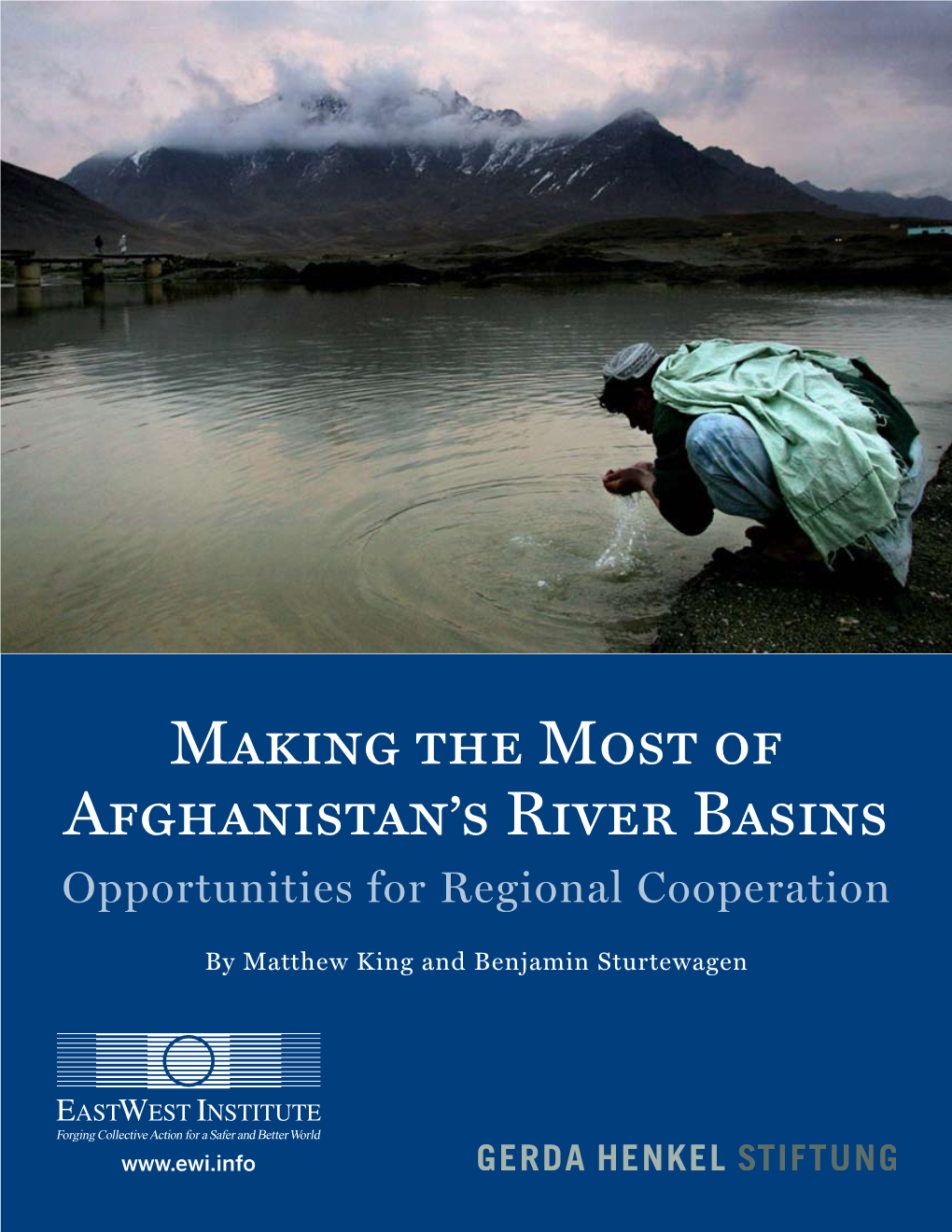

Making the Most of Afghanistan's River Basins

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents List of Abbreviations

وضعیت محیط زیست افغانستان فشارها، پیشرفت ها، چالشها و خﻻها The Environment of Afghanistan ( 2010 - 2017) Pressures, Progress, Challenges/Gaps Ghulam Mohammad Malikyar Dec. 2017 غﻻم محمد ملکیار حوت 1396 1 Table of Contents List of Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................. 6 AFGHANISTAN'S MAJOR ENVIRONMENTAL ASSETS .................................................................................... 10 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... 10 2. Physiography ................................................................................................................................................ 11 3. Population and Population growth ............................................................................................................... 12 4. General Education and Environmental Education ....................................................................................... 12 5. Socio-economic Process and Environment ................................................................................................... 13 6. Health and Sanitation ................................................................................................................................... 14 .[3] ........................................................................................................................................................................... -

BACKGROUNDER Military a Nalysis Andeducation for Civilian Leaders June 10, 2010

INSTITUTE FOR THE Jeffrey Dressler STUDY of WAR BACKGROUNDER Military A nalysis andEducation for Civilian Leaders June 10, 2010 Will the Marines Push into Northern Helmand? Northern Helmand may be the next focal point narcotics network and home to large contingents of of U. S. and British efforts in the province, just enemy fighters, IED manufacturing compounds, four months after U.S. Marines launched the and weapons storage caches.4 Sangin and Kajaki massive Operation Moshtarak in Marjah in central initially became hotspots for the Taliban after Helmand.1 This effort, which would be significantly they were driven from Musa Qala in December smaller in size and scope than Marjah, would 2007. Since then, the Taliban have expanded their concentrate on the troublesome districts of Kajaki presence and run mobile courts and effective shadow and Sangin in northeastern Helmand. governance structures in the districts, offering popular and effective services for the population.5 Speaking to reporters in London on June 7, U.S. Taliban elements operate relatively undisturbed Secretary of Defense Robert Gates said he discussed in the dense agricultural expanse that surrounds the possibility of sending more U.S. forces to both banks of the Helmand River to the south and northeastern Helmand.2 However, Gates noted that north of Sangin. Afghan, U.S., and coalition forces any final decision would be up to General Stanley in the area have been able to conduct only limited McChrystal, commander of U.S. and NATO forces patrolling beyond the district centers and the area in Afghanistan. surrounding the Kajaki dam, which provides power for much of Helmand and portions of Kandahar. -

Supplement 1

*^b THE BOOK OF THE STATES .\ • I January, 1949 "'Sto >c THE COUNCIL OF STATE'GOVERNMENTS CHICAGO • ••• • • ••'. •" • • • • • 1 ••• • • I* »• - • • . * • ^ • • • • • • 1 ( • 1* #* t 4 •• -• ', 1 • .1 :.• . -.' . • - •>»»'• • H- • f' ' • • • • J -•» J COPYRIGHT, 1949, BY THE COUNCIL OF STATE GOVERNMENTS jk •J . • ) • • • PBir/Tfili i;? THE'UNIfTED STATES OF AMERICA S\ A ' •• • FOREWORD 'he Book of the States, of which this volume is a supplement, is designed rto provide an authoritative source of information on-^state activities, administrations, legislatures, services, problems, and progressi It also reports on work done by the Council of State Governments, the cpm- missions on interstate cooperation, and other agencies concepned with intergovernmental problems. The present suppkinent to the 1948-1949 edition brings up to date, on the basis of information receivjed.from the states by the end of Novem ber, 1948^, the* names of the principal elective administrative officers of the states and of the members of their legislatures. Necessarily, most of the lists of legislators are unofficial, final certification hot having been possible so soon after the election of November 2. In some cases post election contests were pending;. However, every effort for accuracy has been made by state officials who provided the lists aiid by the CouncJLl_ of State Governments. » A second 1949. supplement, to be issued in July, will list appointive administrative officers in all the states, and also their elective officers and legislators, with any revisions of the. present rosters that may be required. ^ Thus the basic, biennial ^oo/t q/7^? States and its two supplements offer comprehensive information on the work of state governments, and current, convenient directories of the men and women who constitute those governments, both in their administrative organizations and in their legislatures. -

Characteristics of Water in Iranian Culture and Architecture

The Turkish Online Journal of Design, Art and Communication - TOJDAC November 2016 Special Edition EVALUATION OF SEMANTIC (CONCEPTUAL) CHARACTERISTICS OF WATER IN IRANIAN CULTURE AND ARCHITECTURE Hooman Sobouti Assistant Professor, Department of Architecture, Zanjan Branch, Islamic AzaUniversity, Zanjan, Iran and Young Researchers and Elite Club, Zanjan Branch, Islamic Azad University, Zanjan, Iran Kiana Mohammadi M.Sc.Architecture,Department of Architecture, Central Tehran Branch Faculty, Islamic Azad University ,Tehran, Iran ABSTRACT Water in different cultures defines different symbolic meanings and every country depending on its climate, religion and historical experiences embedded different concepts and meaning of the water in their culture. In Iran, due to arid and hot climate there is high consideration focused on the water and looking at historical Iranian background we would find that Iranian from ancient tiles respected highly the water. In this research, using library sources and analytic-descriptive methodology, the semantic (conceptual) characteristics of the water are investigated in Iranian culture and architecture in several periods of the history. Public believes and ideas ion Iranian rich culture about water are very extensive and spreading. The water natural purity from ancient time so far, brought different beliefs in Iranian culture. Keywords: organizational silence, organizational commitment, organizational trust RESEARCH THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS WATER MEANING FINDING EXAMPLES IN PRE-ARYAN CULTURES The geological information indicates that about 10 thousand years ago, Iran was a suitable land and environment for Iranian societies living. Documents and evidence based on the myths, the oral tradition and ancient environment findings also confirm this issue. Among the remained works from pre-Aryan age, there are dissociated indicators and signs which show the importance and mythical place of the water in pre-Aryan cultures. -

Issue 2 Page 88-175 (2014) Table of Contents/İçerik 1

Journal of FisheriesSciences.com E-ISSN 1307-234X © 2014 www.fisheriessciences.com Journal of FisheriesSciences.com E-ISSN 1307-234X is published in one volume of four issues per year by www.FisheriesSciences.com. Contact e-mail: [email protected] and [email protected] Copyright © 2014 www.fisheriessciences.com All rights reserved/Bütün hakları saklıdır. Aims and Scope The Journal of FisheriesSciences.com publishes peer-reviewed articles that cover all aspects of fisheries sciences, including fishing technology, fisheries management, sea foods, aquatic (both freshwater and marine) systems, aquaculture systems and health management, aquatic food resources from freshwater, brackish and marine environments and their boundaries, including the impact of human activities on these systems. As the specified areas inevitably impinge on and interrelate with each other, the approach of the journal is multidisciplinary, and authors are encouraged to emphasise the relevance of their own work to that of other disciplines. This journal published articles in English or Turkish. Chief editor: Prof. Dr. Özkan ÖZDEN (Istanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Editorial assistant: Dr. Ferhat ÇAĞILTAY (Istanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Dr. Deniz TOSUN (Istanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Cover photo: Prof. Dr. Nuray ERKAN (Istanbul University, Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) I Editorial board: Prof. Dr. Ahmet AKMIRZA (Istanbul Univ., Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Prof. Dr. Levent BAT (Sinop Univ., Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Prof. Dr. Bela H. BUCK (Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, Germany) Prof. Dr. Fatih CAN (Mustafa Kemal Univ., Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Prof. Dr. Şükran ÇAKLI (Ege Univ., Faculty of Fisheries, Turkey) Prof. -

Water Conflict Management and Cooperation Between Afghanistan and Pakistan

Journal of Hydrology 570 (2019) 875–892 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Hydrology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jhydrol Research papers Water conflict management and cooperation between Afghanistan and T Pakistan ⁎ Said Shakib Atefa, , Fahima Sadeqinazhadb, Faisal Farjaadc, Devendra M. Amatyad a Founder and Transboundary Water Expert in Green Social Research Organization (GSRO), Kabul, Afghanistan b AZMA the Vocational Institute, Afghanistan c GSRO, Afghanistan d USDA Forest Service, United States ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT This manuscript was handled by G. Syme, Managing water resource systems usually involves conflicts. Water recognizes no borders, defining the global Editor-in-Chief, with the assistance of Martina geopolitics of water conflicts, cooperation, negotiations, management, and resource development. Negotiations Aloisie Klimes, Associate Editor to develop mechanisms for two or more states to share an international watercourse involve complex networks of Keywords: natural, social and political system (Islam and Susskind, 2013). The Kabul River Basin presents unique cir- Water resources management cumstances for developing joint agreements for its utilization, rendering moot unproductive discussions of the Transboundary water management rights of upstream and downstream states based on principles of absolute territorial sovereignty or absolute Conflict resolution mechanism territorial integrity (McCaffrey, 2007). This paper analyses the different stages of water conflict transformation Afghanistan -

Water Dispute Escalating Between Iran and Afghanistan

Atlantic Council SOUTH ASIA CENTER ISSUE BRIEF Water Dispute Escalating between Iran and Afghanistan AUGUST 2016 FATEMEH AMAN Iran and Afghanistan have no major territorial disputes, unlike Afghanistan and Pakistan or Pakistan and India. However, a festering disagreement over allocation of water from the Helmand River is threatening their relationship as each side suffers from droughts, climate change, and the lack of proper water management. Both countries have continued to build dams and dig wells without environmental surveys, diverted the flow of water, and planted crops not suitable for the changing climate. Without better management and international help, there are likely to be escalating crises. Improving and clarifying existing agreements is also vital. The United States once played a critical role in mediating water disputes between Iran and Afghanistan. It is in the interest of the United States, which is striving to shore up the Afghan government and the region at large, to help resolve disagreements between Iran and Afghanistan over the Helmand and other shared rivers. The Atlantic Council Future Historical context of Iran Initiative aims to Disputes over water between Iran and Afghanistan date to the 1870s galvanize the international when Afghanistan was under British control. A British officer drew community—led by the United States with its global allies the Iran-Afghan border along the main branch of the Helmand River. and partners—to increase the In 1939, the Iranian government of Reza Shah Pahlavi and Mohammad Joint Comprehensive Plan of Zahir Shah’s Afghanistan government signed a treaty on sharing the Action’s chances for success and river’s waters, but the Afghans failed to ratify it. -

Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus

0 [Type here] Irrigation in Africa in figures - AQUASTAT Survey - 2016 Transboundary River Basin Overview – Indus Version 2011 Recommended citation: FAO. 2011. AQUASTAT Transboundary River Basins – Indus River Basin. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO). Rome, Italy The designations employed and the presentation of material in this information product do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) concerning the legal or development status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The mention of specific companies or products of manufacturers, whether or not these have been patented, does not imply that these have been endorsed or recommended by FAO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. The views expressed in this information product are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of FAO. FAO encourages the use, reproduction and dissemination of material in this information product. Except where otherwise indicated, material may be copied, downloaded and printed for private study, research and teaching purposes, or for use in non-commercial products or services, provided that appropriate acknowledgement of FAO as the source and copyright holder is given and that FAO’s endorsement of users’ views, products or services is not implied in any way. All requests for translation and adaptation rights, and for resale and other commercial use rights should be made via www.fao.org/contact-us/licencerequest or addressed to [email protected]. -

Making the Most of Afghanistan's River Basins

Making the Most of Afghanistan’s River Basins Opportunities for Regional Cooperation By Matthew King and Benjamin Sturtewagen www.ewi.info About the Authors Matthew King is an Associate at the EastWest Institute, where he manages Preventive Diplomacy Initiatives. Matthew’s main interest is on motivating preventive action and strengthening the in- ternational conflict prevention architecture. His current work focuses on Central and South Asia, including Afghanistan and Iran, and on advancing regional solutions to prevent violent conflict. He is the head of the secretariat to the Parliamentarians Network for Conflict Prevention and Human Security. He served in the same position for the International Task Force on Preventive Diplomacy (2007–2008). King has worked for EWI since 2004. Before then he worked in the legal profession in Ireland and in the private sector with the Ford Motor Company in the field of change management. He is the author or coauthor of numerous policy briefs and papers, including “New Initiatives on Conflict Prevention and Human Security” (2008), and a contributor to publications, including a chapter on peace in Richard Cuto’s Civic and Political Leadership (Sage, forthcoming). He received his law degree from the University of Wales and holds a master’s in peace and conflict resolution from the Centre for Conflict Resolution at the University of Bradford, in England. Benjamin Sturtewagen is a Project Coordinator at the EastWest Institute’s Regional Security Program. His work focuses on South Asia, including Afghanistan, Pakistan, and Iran, and on ways to promote regional security. Benjamin has worked for EWI since April 2006, starting as a Project Assistant in its Conflict Prevention Program and later as Project Coordinator in EWI’s Preventive Diplomacy Initiative. -

An Etymological Study of Mythical Lakes in Iranian "Bundahišn"

Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 6 No. 6; December 2015 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Flourishing Creativity & Literacy An Etymological Study of Mythical Lakes in Iranian Bundahišn Hossein Najari (Corresponding author) Shiraz University, Eram Square, Shiraz, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Zahra Mahjoub Shiraz University, Shiraz, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.174 Received: 30/07/2015 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.6n.6p.174 Accepted: 02/10/2015 Abstract One of the myth-making phenomena is lake, which has often a counterpart in reality. Regarding the possible limits of mythological lakes of Iranian Bundahišn, sometimes their place can be found in natural geography. Iranian Bundahišn, as one of the great works of Middle Persian (Pahlavi) language, contains a large number of mythological geography names. This paper focuses on the mythical lakes of Iranian Bundahišn. Some of the mythical lakes are nominally comparable to the present lakes, but are geographically located in different places. Yet, in the present research attempt is made to match the mythical lakes of Iranian Bundahišn with natural lakes. Furthermore, they are studied in the light of etymological and mythological principles. The study indicates that mythical lakes are often both located in south and along the "Frāxkard Sea" and sometimes they correspond with the natural geography, according to the existing mythological points and current characteristics of the lakes. Keywords: mythological geography, Bundahišn, lake, Iranian studies, Middle Persian 1. Introduction Discovering the geographical location of mythical places in our present-day world is one of the most noteworthy matters for mythologists. -

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan

The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2012 © 2012 George Fiske All rights reserved ABSTRACT The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan George Fiske This study examines the socioeconomics of state formation in medieval Afghanistan in historical and historiographic terms. It outlines the thousand year history of Ghaznavid historiography by treating primary and secondary sources as a continuum of perspectives, demonstrating the persistent problems of dynastic and political thinking across periods and cultures. It conceptualizes the geography of Ghaznavid origins by framing their rise within specific landscapes and histories of state formation, favoring time over space as much as possible and reintegrating their experience with the general histories of Iran, Central Asia, and India. Once the grand narrative is illustrated, the scope narrows to the dual process of monetization and urbanization in Samanid territory in order to approach Ghaznavid obstacles to state formation. The socioeconomic narrative then shifts to political and military specifics to demythologize the rise of the Ghaznavids in terms of the framing contexts described in the previous chapters. Finally, the study specifies the exact combination of culture and history which the Ghaznavids exemplified to show their particular and universal character and suggest future paths for research. The Socioeconomics of State Formation in Medieval Afghanistan I. General Introduction II. Perspectives on the Ghaznavid Age History of the literature Entrance into western European discourse Reevaluations of the last century Historiographic rethinking Synopsis III. -

Lucy Morgan Edwards to the University of Exeter As a Thesis for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics by Publication, in March 2015

Western support to warlords in Afghanistan from 2001 - 2014 and its effect on Political Legitimacy Submitted by Lucy Morgan Edwards to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Politics by Publication, in March 2015 This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certifythat all the material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted or approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. !tu ?"\J�� Signature. ... .......................L�Uv) ......... ...!} (/......................., ................................................ 0 1 ABSTRACT This is an integrative paper aiming to encapsulate the themes of my previously published work upon which this PhD is being assessed. This work; encompassing several papers and various chapters of my book are attached behind this essay. The research question, examines the effect of Western support to warlords on political legitimacy in the post 9/11 Afghan war. I contextualise the research question in terms of my critical engagement with the literature of strategists in Afghanistan during this time. Subsequently, I draw out themes in relation to the available literature on warlords, politics and security in Afghanistan. I highlight the value of thinking about these questions conceptually in terms of legitimacy. I then introduce the published work, summarising the focus of each paper or book chapter. Later, a ‘findings’ section addresses how the policy of supporting warlords has affected legitimacy through its impact on security and stability, the political settlement and ultimately whether Afghans choose to accept the Western-backed project in Afghanistan, or not.