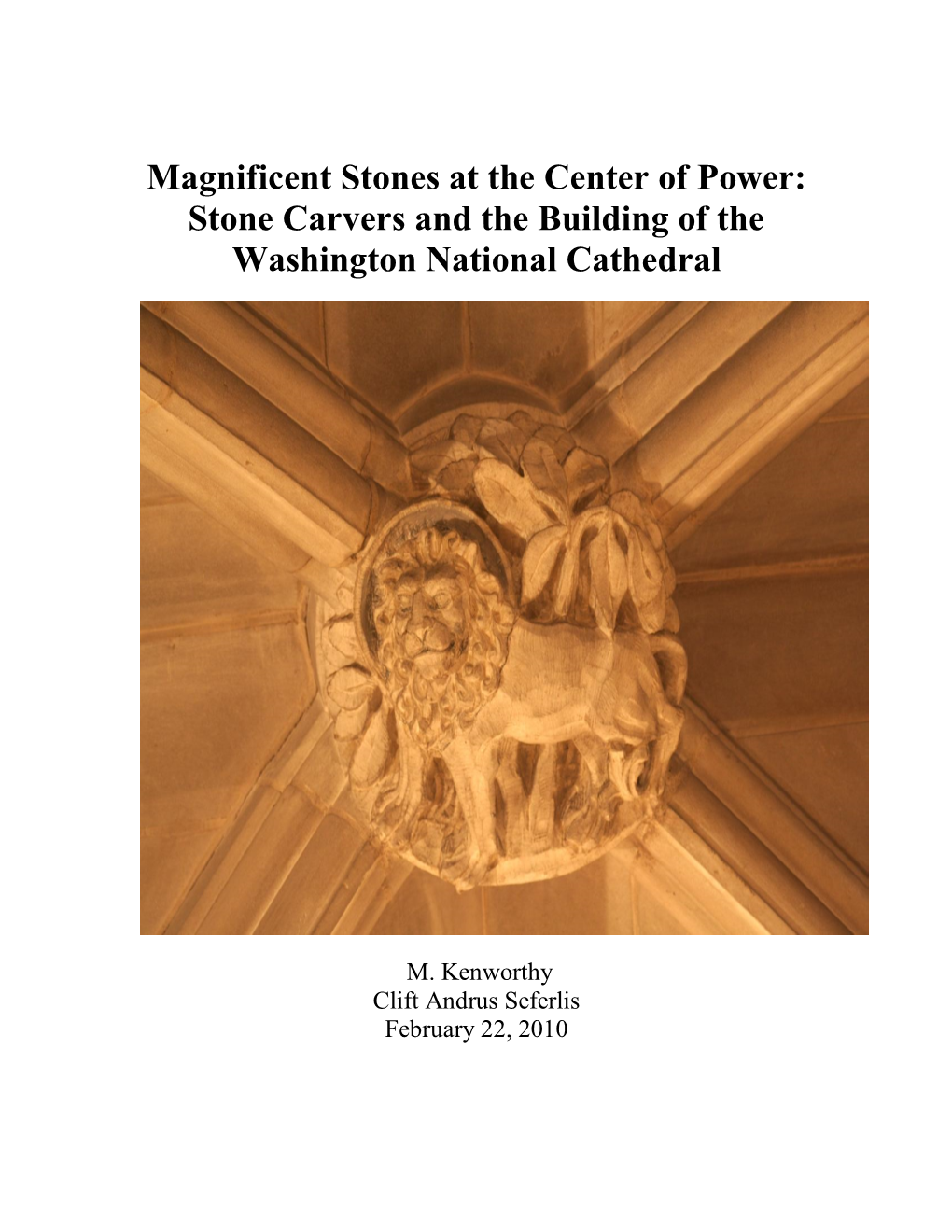

Stone Carvers and the Building of the Washington National Cathedral

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Polk County Courthouse Past Present and Future

THE POLK COUNTY COURTHOUSE PAST PRESENT AND FUTURE POLK COUNTY BAR ASSOCIATION FALL GENERAL PRACTICE SEMINAR November 18, 2016 Des Moines, Iowa Hon. Arthur E. Gamble Chief Judge of the Fifth Judicial District of Iowa Polk County Courthouse 500 Mulberry St. Des Moines, IA 50309 Phone (515) 286-3853 1 THE POLK COUNTY COURTHOUSE PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE Arthur E. Gamble Chief Judge of the Fifth Judicial District of Iowa November 18, 2016 A. Introduction. “Our liberties we prize and our rights we will maintain.” This familiar motto is inscribed on the Great Seal and State flag of Iowa. In the State of Iowa and in the County of Polk, our rights and liberties as freedom loving Americans are maintained and preserved in our county courthouse. In Iowa and throughout the United States, the courthouse is the seat of county government and the place of holding court in the county. It sits prominently in the town center where the social, economic, and political values of the county converge. The courthouse is the place where citizens participate directly in their government through their interaction with the Iowa Judicial Branch. The courthouse is the transcendent symbol of liberty and democracy in the county, in the state and in our country. The courthouse is the epicenter of truth and justice in the community. It is the place where civil disputes between citizens are resolved, children are protected from abuse, crime victims are vindicated and the constitutional rights of the accused are maintained. Ultimately, the courthouse stands as an anchor of stability, dignity and ceremony for the people of the county. -

Lions and LCIF Provide Food Relief After August Derecho

The IOWA LION Dec. 2020 / Jan. 2021 iowalions.org Lions and LCIF Provide Food Relief After August Derecho By PDG Jim Bixler In 9EC, District Governor Stan Stanfield provided MD9 LCIF Coordinator leadership in coordinating the district’s disaster response 2020 has been across his district. Funds were pooled together from an a challenging year, LCIF Emergency grant ($10,000), District and Club especially with Community grant ($3,000) and the district Care and the COVID-19 Share fund ($6,000). These were distributed in Cedar pandemic impacting Rapids, Mount Vernon and the Clinton area. our nation’s and This is how DG Stan summed up the work: world’s norms. The Cedar Rapids Lions Club received $10,000 in LCIF stepped up to assistance, purchased food and distributed it through help provide grants Hawkeye Area Community Assistance Program. through June of this Several pallets of food were purchased on Aug. 27 and year to multiples NO POWER, NO PROBLEM. distributed on Sept. 3rd to provide more than 8,500 and districts meals to some 2,500 households in the Cedar Rapids/ in this country Mount Vernon Lions provide a hot meal of burgers and hot dogs to Marion area. The food was distributed by community (Constitutional residents who lost power in the Area 1) and around Aug. 10 derecho. CONTINUED ON PAGE 22 the world with 348 grants totaling $5,225,246. CA1 received $856,802 in 70 grants. 9SE received $10,000 for PPE that was distributed in the district. The derecho of Aug. 10 left a path of destruction in Iowa that affected rural and metropolitan areas alike. -

Blue Sky White Stars by Sarvinder Naberhaus

INSTRUCTIONS APRIL 2021 Blue Sky White Stars by Sarvinder Naberhaus Book Synopsis: Blue Sky White Stars by Sarvinder Naberhaus and illustrated by Kadir Nelson is a simple, yet powerful story celebrating the United States and the American flag. Using words pulled from patriotic materials, the beautiful illustrations help tell a variety of stories from across the nation. A recorded reading of this book is available here. Connection to Iowa History During World War I, Iowa National Guardsmen recognized the need for an official state flag, as Iowa did not have a state flag to fly. A flag design submitted by Dixie Cornell Gebhardt, of Knoxville, was chosen in a contest held by the Iowa Society of the Daughters of the American Revolution. The design was adopted as the official state flag on March 29, 1921. The original flag design and a portrait of Dixie Cornell Gebhart are held in the collection of the State Historical Museum of Iowa. Goldie’s Kids Club Storytime Activity After reading or listening to the book, use the activity sheet to create and design your own state flag for Iowa. Instructions (Video Instructions Available) 1 Examine. Using the activity sheet, look closely and investigate the official state flag of Iowa. Materials • Iowa Flag activity 2 Take notes. Answer the provided questions to gain a better understanding of worksheet the flag. Why do you think the flag was designed this way? • Colored pencils or 3 Brainstorm. Using the provided prompts, write your answers to the markers questions to help develop the design of your own Iowa flag. -

State Flags-Part II

The Little Bird© A Twice-Weekly Newsletter For Curious Seniors Nancy A. Franks, Editor Topic: State Flags - Part II “Where’d you hear that?” “The Little Bird© told me!” Arkansas Iowa Florida Source: (Photo usflagstore.com) (Photo Source: usflagstore.com) (Photo Source: usflagstore.com) When the Pine Bluff, Arkansas It’s no coincidence that the flag of Iowa In 1985, revisions were made to the chapter of the Daughters of The resembles the flag of France. When seal that had appeared on the Florida American Revolution (DAR) wanted designing the flag, Dixie Cornell state flag since 1900. A palmetto tree to present a state flag to the newly Gebhardt wanted to honor the French replaced a cocoa tree. Mountains were commissioned USS Arkansas in 1911, Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte and the taken away to reflect the flat land of there was a big problem. The state state’s strong connection to France. the state. The headdress on the Native didn’t have an official flag. At the All of the land that would become the American woman was removed to urging of the DAR, the Secretary Of state of Iowa was sold to Thomas accurately depict Seminole traditions. State held a contest. The committee Jefferson by Napoleon during the The Florida flag is one of just three chose a design submitted by Louisiana Purchase. Dixie’s flag was flags that include the words, In God schoolteacher Willie Kavanaugh adopted in May 1917. The governor We Trust. The other two are the flags Hooker. On a rectangular field of red, called Dixie, “Iowa’s Betsy Ross”. -

A Comparison of the Floras of Southwestern Wisconsin and Northeastern Iowa

Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science Volume 64 Annual Issue Article 24 1957 A Comparison of the Floras of Southwestern Wisconsin and Northeastern Iowa Thomas G. Hartley State University of Iowa Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy Copyright ©1957 Iowa Academy of Science, Inc. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias Recommended Citation Hartley, Thomas G. (1957) "A Comparison of the Floras of Southwestern Wisconsin and Northeastern Iowa," Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science, 64(1), 199-204. Available at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/pias/vol64/iss1/24 This Research is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa Academy of Science at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Proceedings of the Iowa Academy of Science by an authorized editor of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hartley: A Comparison of the Floras of Southwestern Wisconsin and Northeas A Comparison of the Floras of South .. western Wisconsin and Northeastern Iowa By THOMAS G. HARTLEY Botanically and geologically, one of the most interesting areas in the Upper Middle West is the "Driftless Area." Covering 15,000 square miles of southwestern Wisconsin and adjacent Illinois, Iowa and Minnesota, this area is about twice the size of the state of New Illinois Jersey. With the exception of certain marginal areas such as north eastern Iowa, the "Driftless Area" was apparently not covered by a continental glacier during the periodic glaciation of the Pleistocene epoch. These marginal areas are believed to have been glaciated . -

Fall 2012 Layout.Indd

OfficialOfficial Publication Publication of of the the Iowa Iowa National National Guard Guard WinterFall 2011 2012 e Iowa National Guard JCEP = JOB SUCCESS IOWA - KOSOVO PARTNERSHIP GRUELING LEADER TEST Fall 2012 | The Iowa Militiaman | 1 4 Fall 2012 Th e Adjutant General Maj. Gen. Tim Orr Public Aff airs Offi cer Col. Greg Hapgood Building blocks to job success Editor/Designer Master Sgt. Duff McFadden Master Sgt. Duff E. McFadden State Photographer Staff Sgt. Chad D. Nelson Contributing Writers/Photographers: Lt. Col. Travis "Chicken" Acheson Features 8 1st Lt. Brandon Cochran by 2nd Lt. Jeremy McClure Th e Iowa Militiaman is an offi cial publication Iowa-Kosovo collaborate authorized under the provisions of AR 360-1. It is Sgt. 1st Class Jeremy L. Harpold published by the Iowa National Guard State Public Aff airs Offi ce and is printed four times annually. News and opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Adjutant General 1100 of Iowa or the Department of Defense. Full color version available online at www.iowanationalguard.com/ 23rd Bataan Death March publicaff airs/militiaman.htm Master Sgt. Duff E. McFadden Follow the Iowa National Guard on Facebook » Ordnance award to Iowans 7 www.facebook.com/IowaNationalGuard Staff Sgt. Chad D. Nelson 14 » A grueling leadership test Address all submissions to: Sgt. Adrian Muehe Th e Iowa National Guard Militiaman Magazine State Public Aff airs Offi ce 19 » Classic A-7 Corsair restored 7105 NW 70th Ave. by Master Sgt. Bill Wiseman Johnston, Iowa 50131-1824 or e-mail: [email protected] 3 TAG Sends Comm: (515) 252-4582 DSN: 431-4582 Maj. -

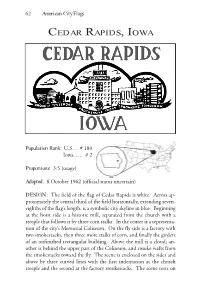

Cedar Rapids, Iowa

62 American City Flags CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA Population Rank: U.S... # 180 Iowa...... # 2 Proportions: 3:5 (usage) Adopted: 8 October 1962 (official status uncertain) DESIGN: The field of the flag of Cedar Rapids is white. Across ap- proximately the central third of the field horizontally, extending seven- eighths of the flag’s length, is a symbolic city skyline in blue. Beginning at the hoist side is a historic mill, separated from the church with a steeple that follows it by three corn stalks. In the center is a representa- tion of the city’s Memorial Coliseum. On the fly side is a factory with two smokestacks, then three more stalks of corn, and finally the girders of an unfinished rectangular building. Above the mill is a cloud; an- other is behind the upper part of the Coliseum; and smoke wafts from the smokestacks toward the fly. The scene is enclosed on the sides and above by three curved lines with the first indentation at the church steeple and the second at the factory smokestacks. The scene rests on Cedar Rapids, Iowa 63 a blue heraldic ribbon on which the city’s motto appears in white (with quotation marks): “PROUD of YESTERDAY [below the mill and church] PROGRESSIVE TODAY [below the Coliseum] PROMIS- ING TOMORROW” [below the factory and unfinished building]. Above the scene, running across the field nearly the same length as the scene is CEDAR RAPIDS; below, centered below the central segment of the scene is IOWA, all in large red letters. SYMBOLISM: In 1963 the city administration explained the flag’s symbolism: Red, white, and blue are the three basic colors because they are the basic colors of both the American flag and the flag of Iowa. -

Driftless Area Streams Is Also Provided to Assist in Developing the Regional and Property Analysis That Is Part of the Master Plan

Rapid Ecological Assessment for Driftless Area Study Streams A Rapid Ecological Assessment Focusing on Rare Plants, Selected Rare Animals, and High-quality Natural Communities Properties included in this report are listed on the next two pages Wisconsin’s Natural Heritage Inventory Program Bureau of Endangered Resources Department of Natural Resources June 2012 P.O. Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707 PUB-ER-836 2012 Properties included in this report, grouped by county: Chippewa ▪ Elk Creek Fishery Area Jackson ▪ Sand Creek Fishery Area ▪ Albion Rearing Station ▪ Beaver Creek Rearing Station Crawford ▪ Buffalo River Fishery Area ▪ Gordon's Bay Landing Public Access ▪ Buffalo River Trail Prairies SNA ▪ La Crosse Area Comprehensive Fishery ▪ Half Moon Bottoms SNA Area ▪ Half Moon Lake Fishery Area/Statewide ▪ Statewide Public Access Habitat Areas ▪ Stream Bank Protection Fee Program ▪ Halls (Stockwell) Creek Fishery Area ▪ Rush Creek SNA (FM-owned parcels) ▪ North Branch Trempealeau River Fishery Area Dane ▪ REM-So Branch Trempealeau River ▪ Black Earth Creek Fishery Area ▪ REM-Washington Coulee ▪ Mount Vernon Creek Fishery Area ▪ Sand Creek Streambank Protection ▪ REM-Elvers Creek Area ▪ Stream Bank Protection Fee Program ▪ Smith Pond Fishery Area ▪ Stream Bank Protection Fee Program Dunn ▪ Tank Creek Fishery Area ▪ Bolen Creek Fishery Area ▪ Trump Coulee Rearing Station ▪ Lake Menomin Fishery Area ▪ REM-Elk Creek La Crosse ▪ REM-Gilbert Creek ▪ Statewide Habitat Areas ▪ REM-Otter Creek ▪ Coon Creek Fishery Area ▪ REM-Tainter Lake Spawning Marsh -

Deployment Alert Potentially Iowa's Largest Activation Since WWII

What do families need to do to prepare for a deployment? WINTER 2009 2nd BCT Deployment Alert Potentially Iowa's largest activation since WWII Welcome Home Ceremonies // Iowa Gold Star Museum Building Update // 132nd FW Returns Home The Iowa Militiaman | 1 4 Winter 2009 2-34th BCT Deployment Alert Maj. Mike Wunn The Adjutant General Brig. Gen. Tim Orr Public Affairs Officer Lt. Col. Greg Hapgood Editor/Designer Staff Sgt. Jeremy Tevis Copy Editor Staff Sgt. Ashlee Lolkus State Photographer Justin Cato Features 8 Contributing Writers/Photographers: Brig. Gen. Tim Orr Senior Master Sgt. Tim Day Retired Col. Russ Bierl Retired Master Sgt. Welcome Home Ceremonies Lt. Col. James Freese John Talbott 2nd Lt. Brandon Cochran Maj. Mike Wunn Staff Sgt. Scott Campbell Chaplain Maj. Mike Crawford Staff Sgt. Rich Murphy Capt. Tim Mills Spec. Kelsey Blankenship 1st Lt. Gabe Haugland Spec. Cassandra Monroe 2nd Lt. Brandon Cochran Spec. Tim Nash Command Sgt. Maj. Gina Golden 10 John Breitsprecker Renee Mulvey The Iowa Militiaman is an unofficial publication authorized under the provisions of AR 360-1. It is published by the Iowa National Guard Public 132nd FW Returns Home Affairs Office and is printed four times annually. Lt. Col. James Freese News and opinions expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the Adjutant General 12 » 2nd Lt. Scott Baraibar of Iowa or the Department of Defense. Federal OCS Commission 1st Lt. Gabe Haugland Full color version available online at www.iowanationalguard.com/ publicaffairs/militiaman.htm 14 » 185th ARW KC-135 Upgrades Staff Sgt. Rich Murphy Address all submissions to: The Iowa Militiaman 15 » New Vehicle Maintenance Public Affairs Office Building at the 133rd TS 7105 NW 70th Ave. -

Byways of Iowa Foundation

GroupByways Travel of ItinerariesIowa Whether Iowa is your final destination or you’re just passing through, Iowa’s Scenic Byways will make your trip exciting and memorable. Each with their own unique stories, history, and attractions, these designated routes will keep you coming back to explore. Welcome to Iowa’s Scenic Byways! This project paid for in part by the Iowa Tourism Office. DRIFTLESS AREA SCENIC BYWAY 3 GLACIAL TRAIL RIVER BLUFFS 4 10 SCENIC BYWAY SCENIC BYWAY JEFFERSON HIGHWAY 9 HERITAGE BYWAY DELAWARE CROSSING SCENIC BYWAY 2 LINCOLN HIGHWAY HERITAGE BYWAY GRANT WOOD 10 SCENIC BYWAY 5 WESTERN SKIES SCENIC BYWAY 8 14 IOWA VALLEY SCENIC BYWAY 13 WHITE POLE ROAD SCENIC BYWAY GREAT RIVER ROAD 1 6 NATIONAL SCENIC BYWAY COVERED BRIDGES SCENIC BYWAY 11 LOESS HILLS 7 NATIONAL SCENIC BYWAY HISTORIC HILLS SCENIC BYWAY Covered Bridges Scenic Byway ............................ 5 TableDelaware Crossingof Scenic BywayContents ......................... 8 Driftless Area Scenic Byway ................................ 11 Glacial Trail Scenic Byway ................................. 14 Grant Wood Scenic Byway ................................ 17 Great River Road National Scenic Byway ............ 20 Historic Hills Scenic Byway ................................. 24 Iowa Valley Scenic Byway .................................. 27 Lincoln Highway Heritage Byway ........................ 31 Loess Hills National Scenic Byway ...................... 34 River Bluffs Scenic Byway ................................... 38 Western Skies Scenic Byway ............................... 41 White Pole Road Scenic Byway ........................... 44 3 CBSB CoveredSCENIC BYWAY Bridges Group Travel Itinerary Madison County, Iowa Step into the stories of authentic American heroes and cultural icons in South Central Iowa 5 ? throughout Madison County that have been lovingly preserved. Fans can visit many of the set locations, including the Roseman & Holliwell Covered Bridges. CBSB More of the outdoor type? Explore one of the first state parks in Iowa. -

Carson City, Nevada 57 ✪ CARSON CITY, NEVADA

Carson City, Nevada 57 ✪ CARSON CITY, NEVADA Population Rank: U.S... # 566 Nevada...... # 6 Proportions: 2:3 (official) Adopted: 28 December 1992 (official) DESIGN: The specifications of Carson City’s flag are established in detail by ordinance, based on a field that is 4 by 6 feet. The flag is a horizontal tribar of white, blue, and white stripes, each one foot, four inches wide. The blue stripe is “process blue” and has two narrow white horizontal stripes one inch wide running across it, two and one-half inches from the top and bottom edges of the blue stripe. Over the blue stripe is a modified version of the circular city seal, 20 inches in diam- eter, its center one foot, seven inches from the hoist edge. A white line one inch wide encircles the seal on the portion that rests on the blue stripe. 58 American City Flags The seal itself is enclosed in a narrow blue ring and depicts in its center the dome of the state capitol. Over the capitol fly (on the same pole) the United States flag, and below it, and slightly smaller, the Nevada state flag, both in full color. The white capitol is centered on a silhou- ette of the state in blue. In the upper hoist quadrant of the seal is a very large brown golden eagle (Aquila chrysaetos), in flight toward the fly; about half of its right wing extends beyond the seal onto the blue stripe and its left wing arches over the capitol, but behind the flagpole. Be- hind the eagle and capitol are blue sky and white clouds. -

Iowa Department of Public Defense

Iowa Department of Public Defense ANNUAL REPORT Fiscal Year 2010 Brigadier General Timothy E. Orr The Adjutant General INDEX General The National Guard 1 Missions of the National Guard 1 Responsibilities 2 Iowa Department of Public Defense Authority 2 Staffs of the Adjutant General 3 Military Division State Employee Program 5 State Budget and Fiscal Program 12 Federal Reimbursement Contract Program 13 Contingent Fund Support – Standing Unlimited 14 Appropriations National Guard Facilities Improvement Fund 14 Military Operations Fund 14 Capital Improvements 15 Human Resources Office Federal Support 17 State Support 17 Equal Employment Program 18 Deputy Chief of Staff for Personnel Personnel and Administration Section 19 Officers 19 Enlisted Personnel 21 Recruiting and Retention 23 National Guard Education Assistance Program 23 Awards and Decorations 25 Roll of Retired Iowa National Guard Officers and Enlisted 27 Officer Retirees 27 Enlisted Retirees 28 Iowa Army National Guard Strength Recapitulation 32 Inspector General Program Mission and Function 33 Organization 33 Accomplishments 33 Senior Army Advisor Mission 36 Organization 36 Personnel 36 Functions 36 Iowa Department of Public Defense Annual Report – Fiscal Year 2010 i Selective Service Mission 37 Organization 37 Accomplishments 37 Deputy Chief of Staff for Operations Organization 39 Training 39 Inactive Duty Training 39 Annual Training 40 Active Duty for Operational Support (ADOS) 42 School Training 42 185th Regional Training Institute 43 Mobilization Readiness 45 Provost Marshall