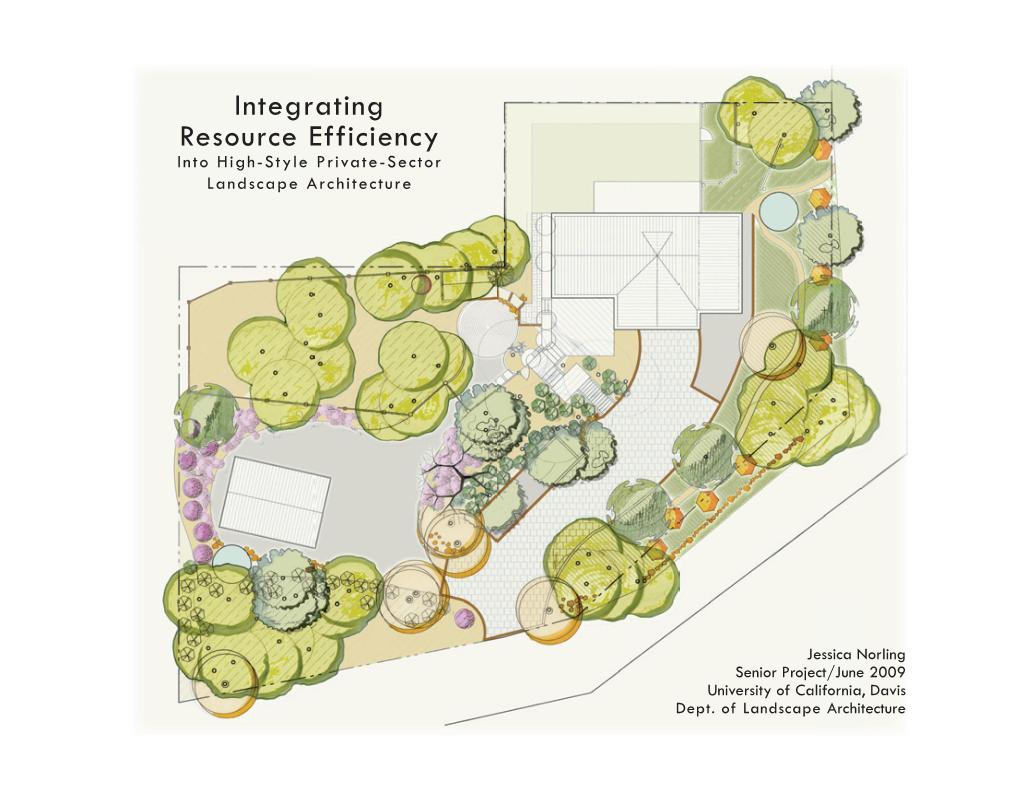

Integrating Resource Efficiency Into High-Style Private-Sector Landscape Architecture

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Community Wildfire Protection Plan Prepared By

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. APRIL - 2 0 1 8 Table of Contents Executive Summary ............................................................................................................ 1 Purpose ................................................................................................................................ 3 Background & Collaboration ............................................................................................... 4 The Landscape .................................................................................................................... 7 The Wildfire Problem ........................................................................................................10 Fire History Map ............................................................................................................... 13 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................14 Reducing Structural Ignitability .........................................................................................16 • Construction Methods ........................................................................................... 17 • Education ............................................................................................................. -

USGS Bulletin 2188, Chapter 7

FieldElements Trip of5 Engineering Geology on the San Francisco Peninsula—Challenges When Dynamic Geology and Society’s Transportation Web Intersect Elements of Engineering Geology on the San Francisco Peninsula— Challenges When Dynamic Geology and Society’s Transportation Web Intersect John W. Williams Department of Geology, San José State University, Calif. Introduction The greater San Francisco Bay area currently provides living and working space for approximately 10 million residents, almost one-third of the population of California. These individuals build, live, and work in some of the most geologically dynamic terrain on the planet. Geologically, the San Francisco Bay area is bisected by the complex and active plate boundary between the North American and Pacific Plates prominently marked by the historically active San Andreas Fault. This fault, arguably the best known and most extensively studied fault in the world, was the locus of the famous 1906 San Francisco earthquake and the more recent 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake. There is the great potential for property damage and loss of life from recurring large-magnitude earthquakes in this densely populated urban setting, resulting from ground shaking, ground rupture, tsunamis, ground failures, and other induced seismic failures. Moreover, other natural hazards exist, including landslides, weak foundation materials (for example, bay muds), coastal erosion, flooding, and the potential loss of mineral resources because of inappropriate land-use planning. The risk to humans and their structures will inexorably increase as the expanding San Francisco Bay area urban population continues to encroach on the more geologically unstable lands of the surrounding hills and mountains. One of the critical elements in the development of urban areas is the requirement that people and things have the ability to move or be moved from location to location. -

La Peninsula Spring 2018

Spring 2018 LaThe Journal of the SanPeninsula Mateo County Historical Association, Volume xlvi, No. 1 Water for San Francisco Our Vision Table of Contents To discover the past and imagine the future. San Mateo County and San Francisco’s Search for Water ............................... 3 by Mitchell P. Postel Our Mission William Bowers Bourn II: To inspire wonder and President of Spring Valley Water Company and Builder of Filoli ....................... 10 by Joanne Garrison discovery of the cultural and natural history of San Images of Building Crystal Springs Dam........................................................... 13 Mateo County. Accredited By the American Alliance of Museums. The San Mateo County Historical Association Board of Directors Barbara Pierce, Chairwoman; Mark Jamison, Vice Chairman; John Blake, Secretary; Christine Williams, Treasurer; Jennifer Acheson; Thomas Ames; Alpio Barbara; Keith Bautista; Sandra McLellan Behling; Elaine Breeze; Chonita E. Cleary; Tracy De Leuw; The San Mateo County Shawn DeLuna; Dee Eva; Ted Everett; Greg Galli; Tania Gaspar; John LaTorra; Emmet Historical Association W. MacCorkle; Olivia Garcia Martinez; Rick Mayerson; Karen S. McCown; Gene Mullin; Mike Paioni; John Shroyer; Bill Stronck; Ellen Ulrich; Joseph Welch III; Darlynne Wood operates the San Mateo and Mitchell P. Postel, President. County History Museum and Archives at the old San President’s Advisory Board Mateo County Courthouse Albert A. Acena; Arthur H. Bredenbeck; David Canepa; John Clinton; T. Jack Foster, Jr.; located in Redwood City, Umang Gupta; Douglas Keyston; Greg Munks; Patrick Ryan; Cynthia L. Schreurs and California, and administers John Schrup. two county historical sites, Leadership Council the Sanchez Adobe in Arjun Gupta, Arjun Gupta Community Foundation; Paul Barulich, Barulich Dugoni Law Pacifica and the Woodside Group Inc; Tracey De Leuw, DPR Construction; Jenny Johnson, Franklin Templeton Store in Woodside. -

Appendix D: Recreation and Education Report Skyline Ridge Open Space Preserve Space Ridge Open Skyline

TAB1 Appendix D TAB2 TAB3 Liv Ames TAB4 TAB5 TAB6 Appendix D: Recreation and Education Report Skyline Ridge Open Space Preserve Space Ridge Open Skyline TAB7 Appendix D-1: Vision Plan Existing Conditions for Access, Recreation and Environmental Education Prepared for: Midpeninsula Regional Open Space District 330 Distel Circle, Los Altos, CA 94022 October 2013 Prepared by: Randy Anderson, Alta Planning + Design Appendix D: Recreation and Education Report CONTENTS Existing Access, Recreation and Environmental Education Opportunities by Subregion ........... 3 About the Subregions ............................................................................................................ 3 Subregion: North San Mateo County Coast ................................................................................... 5 Subregion: South San Mateo County Coast ................................................................................... 8 Subregion: Central Coastal Mountains ....................................................................................... 10 Subregion: Skyline Ridge ....................................................................................................... 12 Subregion: Peninsula Foothills ................................................................................................ 15 Subregion: San Francisco Baylands ........................................................................................... 18 Subregion: South Bay Foothills ............................................................................................... -

2020 ANNUAL REPORT “A Beautiful Setting That Takes Us Away Our Mission: to Connect Our Rich History with a Vibrant Future from the Everyday

2020 ANNUAL REPORT “A beautiful setting that takes us away Our Mission: To connect our rich history with a vibrant future from the everyday. Gorgeous plantings. through beauty, nature and shared stories. Incredible vistas. You Our Vision: A time when all people honor nature, value unique will want to stay for a experiences and appreciate beauty in everyday life. while.” -Andrea Kehe 2 Filoli 2020 Annual Report Table of Contents 4. Messages from the CEO and 30. Making Filoli a Household Board President Name 6. Filoli Leadership 32. Connecting Our Rich History 8. Pandemic Pivot with a Vibrant Future 12. Strategic Plan 34. 2020 Exhibitions 14. Visitor Demographics 36. Seasons of Filoli 16. Financials 38. Holidays at Filoli 18. Epicurean Picnic 40. Building a Culture of Philanthropy 20. Investing in Preservation 50. Ways to Give 26. Curating the Collections Photo by Olivia Richards Cover Photo by Jeff BarteeFiloli 2020 Annual Report 3 A Message of Gratitude We began 2020 at Filoli with great hope and excitement, but the year became something very different than expected. With a worldwide pandemic at our doorstep, we not only had to close Filoli during the magnificent spring display but also had to immediately reduce our operations in anticipation of changing needs. The “Pandemic Pivot” became our new dance, and we came up with creative ways to share Filoli with our visitors, members, donors, and friends. As we gradually began reopening, we leaned into our Strategic Plan to ensure everything we brought back was visitor-centric while safely following public health guidelines. One of our first surprises of 2020 was the overwhelming support of our visitors and donors. -

Phleger Estate

PHLEGER ESTATE PHLEGER ESTATE n 1935, Herman and Mary Elena Phleger purchased their Mountain Meadow property that has come to be known as the Phleger Estate. In 1984, Herman died. IHe and Mary Elena had been life-long boosters of conservation and environmen- tal causes. In that spirit, Mary Elena offered the Peninsula Open Space Trust (POST) the opportunity to preserve the property. Within four years, POST managed to raise the necessary funding to make the purchase possible. On April 29, 1995, the Phleger Estate was dedicated as a part of the GGNRA. The 1,084 acre parcel1 is located west of Cañada Road and north of San Mateo Coun- ty’s Huddart Park in the southern hill country of the Peninsula, once a portion of Ran- cho Cañada de Raymundo in the heart of a robust logging industry during the nine- teenth century. Its western boundary is a forested ridge plainly visible from United States Interstate 280 to the east. This ridge and slope is the eastern portion of Kings Mountain of the Sierra Morena or Santa Cruz Range of Mountains (also referred to as the Skyline) and at 2,315 feet is the second highest point in San Mateo County.2 Three major drainages run from the Mountain into West Union Creek. The Phleger Estate includes redwoods, mixed evergreens and tan oak woodlands. The redwoods are mostly in stream corridors of canyons of the Skyline and also along West Union Creek. These trees include mostly second-growth redwoods, however, the lumberjacks did not take every one of the original sequoias, because a few old growth trees, obviously the more inaccessible ones, live in the upper portions of the property. -

Community Wildfire Protection Plan

Santa Cruz County San Mateo County COMMUNITY WILDFIRE PROTECTION PLAN Prepared by: CALFIRE, San Mateo — Santa Cruz Unit The Resource Conservation District for San Mateo County and Santa Cruz County Funding provided by a National Fire Plan grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service through the California Fire Safe Council. M A Y - 2 0 1 0 Table of Contents Executive Summary.............................................................................................................1 Purpose.................................................................................................................................2 Background & Collaboration...............................................................................................3 The Landscape .....................................................................................................................6 The Wildfire Problem ..........................................................................................................8 Fire History Map................................................................................................................10 Prioritizing Projects Across the Landscape .......................................................................11 Reducing Structural Ignitability.........................................................................................12 • Construction Methods............................................................................................13 • Education ...............................................................................................................15 -

Society for Newsletter

Society for CaliforniaCalifornia ArchaeologyArchaeology Newsletter Founded 1966 Volume 40, Number 1 March 2006 Inside: NAPC Workshop in Big Pine! 2 Society for Volume 40, Number 1 California March 2006 Archaeology Newsletter A quarterly newsletter of articles and information essential to California archaeology. Contributions are welcome. Lead articles should be 1,500-2,000 words. Longer articles may appear in installments. Send submissions as hard copy or on diskette to: SCA Newsletter, Department of Anthropology, CSU Chico, Chico CA 95929-0401 or as email or attachments to: <[email protected]> Regular Features The SCA Executive Board encourages publication of a From the President wide range of opinions on issues pertinent to California Shelly Davis-King . 3 archaeology. Opinions, commentary, and editorials appearing in the Newsletter represent the views of the SCA Business and Activities authors, and not necessarily those of the Board or Editor. Legislative Liaison . 4 Lead article authors should be aware that their articles Archaeology Month . 5 may appear on the SCA web site, unless they request Student Membership Change . 5 otherwise. Proceedings Report . 6 Editorial Staff Annual Meeting Update . 6 Managing Editor . Greg White (530) 898-4360 . [email protected] Southern Data-Sharing Wrap . 6 SCA Archives Project . 9 Contributing Editors Native American Programs. 10 Avocational News . open Education News . open Executive Board Minutes . 12 Curation . Cindy Stankowski Annual Meeting Prelim Program. 15 Federal Agency News. open Field Notes . Michael Sampson New Publications . 16 Historical Archaeology . R. Scott Baxter Web Sites of Interest . 24 Information Centers . Lynn Compas Membership . open News and Announcements New Publications . Denise Jaffke Awards . -

Copyright by Rina Cathleen Faletti 2015

Copyright by Rina Cathleen Faletti 2015 The Dissertation Committee for Rina Cathleen Faletti Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Undercurrents of Urban Modernism: Water, Architecture, and Landscape in California and the American West Committee: Richard Shiff, Co-Supervisor Michael Charlesworth, Co-Supervisor Anthony Alofsin Ann Reynolds Penelope Davies John Clarke Undercurrents of Urban Modernism: Water, Architecture, and Landscape in California and the American West by Rina Cathleen Faletti, B.A., M.F.A., M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2015 Undercurrents of Urban Modernism: Water, Architecture, and Landscape in California and the American West Rina Cathleen Faletti, Ph.D. The University of Texas at Austin, 2015 Co-Supervisors: Richard Shiff and Michael Charlesworth Abstract: “Undercurrents of Urban Modernism: Water, Architecture, and Landscape in California and the American West” conducts an art-historical analysis of historic waterworks buildings in order to examine cultural values pertinent to aesthetics in relationships between water, architecture and landscape in the 19 th and early 20 th centuries. Visual study of architectural style, ornamental iconography, and landscape features reveals cultural values related to water, water systems, landscape/land use, and urban development. Part 1 introduces a historiography of ideas of “West” and “landscape” to provide a context for defining ways in which water and landscape were conceived in the United States during turn-of-the-century urban development in the American West. -

Fall 2017 Newsletter

UTILITAS ! FIRMITAS ! VENUSTAS Northern California Chapter Society of Architectural Historians Volume 20, Number 2 The Newsletter Fall 2017 The Palaces of the San Francisco Peninsula Redux Many members were disappointed when the fall 2016 tour of Peninsula mansions booked up so quickly they could not take advantage of that oppor- tunity. The NCCSAH board has decided to offer those members first crack at a fall tour that will include two of the houses on the earlier program plus a third house not previously open to us. On Wednesday, September 27, partici- pants will gather at Newmar, in Hillsbor- ough, at 10:00 am. Lewis Hobart de- signed the house and landscaping at the estate for San Francisco business- man George A. Newhall. A Spreckels heir acquired the property in 1940 and Green Gables, by Greene and Greene. Photo: Ward Hill changed the name to La Dolphine, by which it is known today. This estate was not on last fall’s program. Lunch will follow at Villa Delizia, much enjoyed by the group who were on the 2016 tour. The day will close with a visit to the Carolands Chateau, the grandest of the Peninsula houses, created for the heiress to the Pullman Railcar fortune. Two days prior to this program, Monday, September 25, the general membership, including those signing up for the tour of September 27, will have the chance to view two other Peninsula properties. We will greet the morning in Woodside at the Fleishhacker summer estate, Green Gables, designed by Greene and Greene. Here our group will have a unique opportunity; the estate manager, Hilary Grenier, will lead the tour. -

Hillsborough's Centennial

Spring 2010 LaThe Journal of the SanPeninsula Mateo County Historical Association, Volume xxxix, No. 1 Hillsborough’s Centennial and the San Mateo County Historical Association’s 75th Anniversary Table of Contents Hillsborough, California: One Hundred Years of Gracious Living ..................... 3 by Joanne Garrison Hillsborough: One Hundred Years of Grand Architecture .............................. 9 by Caroline Serrato San Mateo County Historical Association 1935 - 2010 ................................... 20 by Mitchell P. Postel The San Mateo County Historical Association operates the San Mateo County History Our Vision Museum and research archives at the old San Mateo County Courthouse located in To discover the past and Redwood City, California, and administers two county historical sites, the Sanchez imagine the future. Adobe in Pacifica and the Woodside Store in Woodside. Our Mission The San Mateo County Historical Association Board of Directors To enrich, excite and Keith Bautista, Chairman; Karen McCown, Immediate Past Chairwoman; Peggy Bort educate through Jones, Vice Chairwoman; Phill Raiser, Secretary; Brian Sullivan, Treasurer; John Adams; understanding, preserving June Athanacio; Paul Barulich; Tom Brady; Roberta Carcione; Herm Christensen; Shawn and interpreting the history DeLuna; Celeste Giannini; Umang Gupta; John Inglis; Doug Keyston; Joan Levy; Gene of San Mateo County. Mullin; Barbara Rucker; Patrick Ryan; Cynthia L. Schreurs; Paul Shepherd and Mitchell P. Postel, President. Accredited by the President’s Advisory Board American Association of Albert A. Acena; Arthur H. Bredenbeck; Frank Baldanzi; John Clinton; Robert M. Desky; Museums T. Jack Foster, Jr.; Georgi LaBerge; Greg Munks; John Schrup and Tom Siebel. La Peninsula Carmen J. Blair, Managing Editor Publications Committee: Joan Levy, Publications Chairwoman; Albert A. Acena, PhD; Carmen J. -

The San Francisco Peninsula's Great Estates

Journal of the California Garden & Landscape History Society Vol. 15 No. 2 • Spring 2012 The San Francisco Peninsula’s Great Estates: Part II Mansions, Landscapes, and Gardens in the Late 19th and Early 20th Centuries David C. Streatfield1 [Part I of this article appeared in the Winter 2012 issue of California, and these new developments first appeared in Eden: Vol. 15, No. 1.] the San Francisco Peninsula’s estates. Collectively, these gardens represent a regional design approach based not on y the early 1880s, the Peninsula contained the largest ecology but on the horticultural potential of the climate, constellation of country estates west of the Missis- B which afforded unparalleled opportunities for cultivating a sippi, and their number kept increasing, slowing only dur- very broad range of temperate and subtropical plants. ing the periodic economic recessions that affected Califor- Though the mansions and grounds often resembled similar nia along with the rest of the nation. The existence of these properties in Europe and on the East Coast, their palatial extensive properties, however, was not universally regarded gardens contained an unusually wide variety of plants, most as a beneficial improvement on the Peninsula’s wellbeing. of which could not be grown year-round anywhere else in The original size of the large tracts, whose acreages ranged the United States. (The same horticultural potential began to from several hundred to more than a thousand, was made be exploited in Southern California in a slightly later time possible earlier by the very low prices of the remaining frame and in similarly lavish ways.) former Mexican ranchos.