The Circular Flow of Income

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The National Income Multiplier: Its Theory Its Philosophy Its Utility

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1959 The national income multiplier: Its theory its philosophy its utility John Colin Jones The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Jones, John Colin, "The national income multiplier: Its theory its philosophy its utility" (1959). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 8768. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/8768 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE NATIOHAL INCOME MULTIPLIER; ITS THEORY, ITS PHILOSOPHY, ITS UTILITY J» COLIN H. JONES B.A. University of WaJes^ U.C.W., Aberystwyth, 195Ô Presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY 1959 Approved by: , Board of Examiners Dean, Graduate School AUG 6 1959 D a te UMI Number: EP39569 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Dis»art«t)on Publishsng UMI EP39569 Published by ProQuest LLC (2013). -

"Social Accounting Matrices and SAM-Based Multiplier Analysis"

Chapter 14 – Social Accounting Matrices and SAM-based Multiplier Analysis (Round) Chapter 14 Social Accounting Matrices and SAM-based Multiplier Analysis Jeffery Round1 14.1 Introduction This chapter sets out the framework of a social accounting matrix (SAM) and shows how it can be used to construct SAM-based multipliers to analyse the effects of macroeconomic policies on distribution and poverty. Estimates provided by a social accounting matrix (SAM) can be useful - even essential - for calibrating a much broader class of models to do with monitoring poverty and income distribution. But this chapter is limited to a review of how SAMs are used to develop simple economy-wide multipliers for poverty and income distribution analysis. What is a SAM? A SAM is a particular representation of the macro and meso economic accounts of a socio-economic system, which capture the transactions and transfers between all economic agents in the system (Pyatt and Round, 1985; Reinert and Roland-Holst, 1997). In common with other economic accounting systems it records transactions taking place during an accounting period, usually one year. The main features of a SAM are threefold. First, the accounts are represented as a square matrix; where the incomings and outgoings for each account are shown as a corresponding row and column of the matrix. The transactions are shown in the cells, so the matrix displays the interconnections between agents in an explicit way. Second, it is comprehensive, in the sense that it portrays all the economic activities of the system (consumption, production, accumulation and distribution), although not necessarily in equivalent detail. -

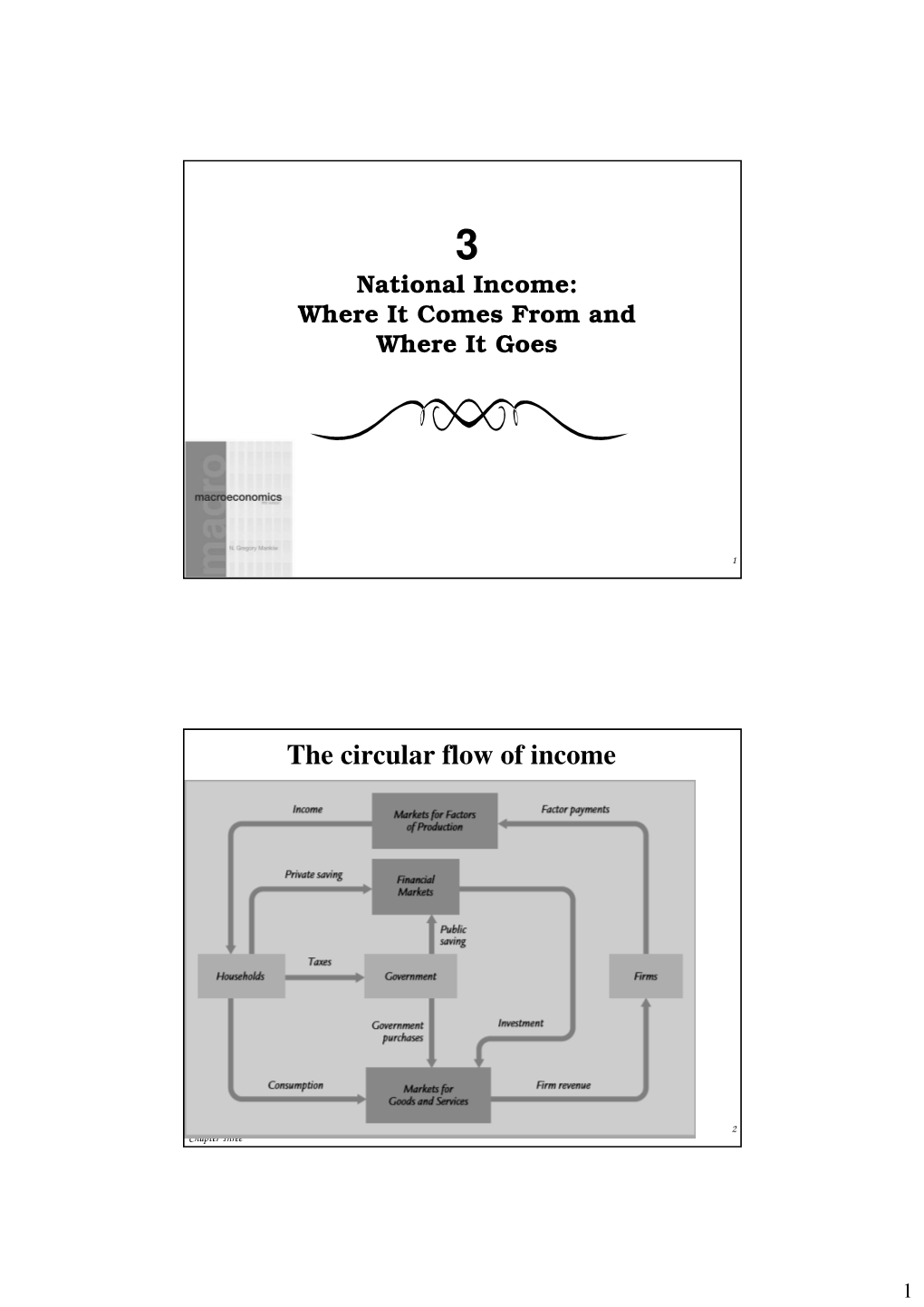

Circular Flow of Income Compiled from Internet

Circular flow of income Compiled from internet (not my own creation) The circular flow of income is a way of representing the flows of money between the two main groups in society - producers (firms) and consumers (households). These flows are part of the fundamental process of satisfying human wants. As we have already seen, a free market economy consists of two components, or sectors, as they are called. These are firms and households. People in households work for firms (selling their factor services) and receive wages in exchange. On the scale of the whole economy, this is known as national income - the total amount of income earned over a given time period. This money is spent on food, clothing, transport, entertainment etc, and so it returns to the firms. This is the circular flow. Figure 1 Circular flow of income We can see this circular flow in Figure 1. Households sell their factor services to firms (in the factor markets) and in exchange receive wages (the left-hand side of the flow). In the meantime, households spend this income on goods and services (in the goods market) and in exchange receive the goods and services themselves (the right-hand side of the flow). Economists call the wages plus the other forms of income, national income and give it the code 'Y'. Domestic consumption is given the code 'C'. Not all income is spent, however. Some is saved. Savings are coded as 'S'. Other money is used to buy goods or services produced overseas. The money to buy these goods and services flows out of the country. -

12 Revision – National Income, Circular Flow, Multiplier

●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●●● 12 Revision – National income, circular flow, multiplier The main economic goals There are usually five economic main aims for 2. A low level of unemployment government. 3. A low and stable rate of inflation 1. A steady rate of increase of national output 4. A favourable balance of payments position (economic growth) 5. An equitable distribution of income. The circular flow of income model Households INVESTMENT SAVING EXPORTS Expenditure Goods and Factors of Wages, rent, IMPORTS on goods and services production interest, and services profits GOVERNMENT Firms TAXES SPENDING Households provide the factors of production and 2. The income method measures the value of receive income. They buy the goods and services all the incomes earned in the economy. produced by the firms which use the income 3. The expenditure method measures the received, and in this way the income circulates value of all spending on goods and services in throughout the economy. the economy. This is calculated by summing The leakages from the system are savings, taxes up the spending by all the different sectors in and imports. The injections are investment, the economy. government spending and exports. The economy In practice, however, the data that is collected to is in equilibrium when leakages are equal to calculate each of the three values comes from injections. many different and varied sources, and inevitably there will be inaccuracies in the data, leading to imbalances among the final values. Measurement of national income Some of these inaccuracies are the result of the The most commonly used measure of a country’s timing of the data gathering; often figures have national income is gross domestic product (GDP). -

Coronavirus and the Effects on UK GDP

Article Coronavirus and the effects on UK GDP How the global coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic and the wider containment efforts are expected to impact on UK gross domestic product (GDP) as well as some of the challenges that National Statistical Institutes are likely to face. Contact: Release date: Next release: Sumit Dey-Chowdhury 6 May 2020 To be announced [email protected]. uk +44 (0)2075 928622 Table of contents 1. Executive summary 2. Background 3. The circular flow of income 4. The treatment of non-market output in GDP 5. The treatment of the CJRS and SEISS in GDP 6. Practical challenges 7. Publications 8. Conclusions 9. Authors Page 1 of 14 1 . Executive summary Forecasters expect the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic to lead to a contraction in the UK and global economy this year, reflecting how it has led to a reduction in the demand for goods and services and the impact on the ability of businesses to supply those products. The impact is expected to reflect the length of the pandemic as well as the public health restrictions imposed and other voluntary social distancing measures. The response to COVID-19 will also impact on the ability of National Statistical Institutes (NSIs) to compile estimates of gross domestic product (GDP), inflation and the labour market. We are responding to these challenges so that we capture the economic activity of the UK in line with the latest international guidance. In this article, we describe how those transactions that are most likely to be impacted by the pandemic will be reflected in the production, income and expenditure measures of GDP ( Section 3), including how we have reflected this accordingly in our volume-based estimates of health and education output ( Section 4). -

Measuring Gdp and Economic Growth

MEASURING GDP Objectives AND ECONOMIC CHAPTER GROWTH 20 After studying this chapter, you will able to Define GDP and use the circular flow model to explain why GDP equals aggregate expenditure and aggregate income Explain the two ways of measuring GDP Explain how we measure real GDP and the GDP deflator Explain how we use real GDP to measure economic growth and describe the limitations of our measure © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 An Economic Barometer Gross Domestic Product GDP Defined What exactly is GDP GDP or gross domestic product, is the market value of How do we use it to tell us whether our economy is in a all final goods and services produced in a country in a recession or how rapidly our economy is expanding? given time period. How do we take the effects of inflation out of GDP to This definition has four parts: compare economic well-being over time Market value And how to we compare economic well-being across Final goods and services counties? Produced within a country In a given time period © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 © Pearson Education Canada, 2003 Gross Domestic Product Gross Domestic Product Final goods and services Market value GDP is the value of the final goods and services produced. GDP is a market value—goods and services are valued at their market prices. A final good (or service), is an item bought by its final user during a specified time period. To add apples and oranges, computers and popcorn, we add the market values so we have a total value of output A final good contrasts with an intermediate good, which is in dollars. -

Macroeconomics II: the Circular Flow of Income

Macroeconomics II: The Circular Flow of Income Gavin Cameron Lady Margaret Hall Hilary Term 2004 introduction • “What is annually saved is as regularly consumed as what is annually spent, and nearly in the same time too; but it is consumed by a different set of people. That portion of his revenue which a rich man annually spends, is in most cases consumed by idle guests…That portion which he annually saves, as for the sake of the profit it is immediately employed as a capital, is consumed in the same manner…but by a different set of people”, Adam Smith, 1776. OECD macroeconomic performance OECD EU USA JAPAN GERMANY FRANCE ITALY UK Output Growth 1960-1973 4.9 4.7 4.0 9.7 4.3 5.4 5.3 3.1 1973-1979 3.2 2.6 2.9 3.5 2.4 2.7 3.5 1.5 1979-1989 2.9 2.2 2.8 3.8 2.0 2.1 2.4 2.4 1989-1999 2.6 2.0 3.0 1.7 2.2 1.7 1.3 1.9 Unemployment 1960-1973 2.9 2.6 4.8 1.2 1.0 2.6 5.7 3.3 1973-1979 5.0 4.6 6.7 1.9 3.0 4.4 6.0 4.9 1979-1989 7.3 9.4 7.3 2.5 5.8 8.8 8.2 9.8 1989-1999 7.4 9.9 5.8 3.1 7.5 11.2 10.9 8.3 Inflation 1960-1973 3.9 4.1 3.1 6.1 3.4 4.9 4.9 4.8 1973-1979 8.8 9.6 7.8 9.5 4.6 11.1 16.7 15.6 1979-1989 5.4 6.6 5.3 2.5 2.8 7.5 11.4 7.0 1989-1999 2.7 3.4 2.4 1.0 2.4 2.1 4.6 3.8 Source: Economics of the OECD 2000 exam paper data tables 1, 4 and 5. -

The Role of Entropy in the Development of Economics

entropy Article The Role of Entropy in the Development of Economics Aleksander Jakimowicz Department of World Economy, Institute of Economics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Palace of Culture and Science, 1 Defilad Sq., 00-901 Warsaw, Poland; [email protected] Received: 25 February 2020; Accepted: 13 April 2020; Published: 16 April 2020 Abstract: The aim of this paper is to examine the role of thermodynamics, and in particular, entropy, for the development of economics within the last 150 years. The use of entropy has not only led to a significant increase in economic knowledge, but also to the emergence of such scientific disciplines as econophysics, complexity economics and quantum economics. Nowadays, an interesting phenomenon can be observed; namely, that rapid progress in economics is being made outside the mainstream. The first significant achievement was the emergence of entropy economics in the early 1970s, which introduced the second law of thermodynamics to considerations regarding production processes. In this way, not only was ecological economics born but also an entropy-based econometric approach developed. This paper shows that non-extensive cross-entropy econometrics is a valuable complement to traditional econometrics as it explains phenomena based on power-law probability distribution and enables econometric model estimation for non-ergodic ill-behaved (troublesome) inverse problems. Furthermore, the entropy economics has accelerated the emergence of modern econophysics and complexity economics. These new directions of research have led to many interesting discoveries that usually contradict the claims of conventional economics. Econophysics has questioned the efficient market hypothesis, while complexity economics has shown that markets and economies function best near the edge of chaos. -

CONCEPT of CIRCULAR FLOW of MONEY Households Give Their Resources and Services to the Firms

Unit ‐ 5 Intorduction to Economics (BHI‐106) Int. MBA (HA) 2nd Semester National income is the flow of goods and services , which becomes available to a nation during a year. • National income is the aggregate money value of all goods and services produced in a country during one year. • The national income may be considered of a closed economy‐an economy, which has no transactions with the rest of the world or an open economy. • In an open economy, national income also includes the net results of its transactions with the rest of the world. I.e. exports less imports. CONCEPT OF NATIONAL INCOME According to Marshall,” the labour and capital of a country, acting upon its natural resources, produced annually a certain net aggregate of commodities, material and immaterial, including services of all kinds .” • According to Pigou,” National income is that part of objective income of the community, including of course income from derived from abroad, which can be measured in money.” According to Fischer,” The national dividend or income consists solery of services as received by ultimate consumers, whether from their material human environments.” Marshall and Pigou approach national income from the point of production. But Fischer approaches from the point of consumption. This income is produced by factors of production and hence distributed between them. These are land, labour , capital and entrepreneur. Higher level of national income implies higher shares of these factors . Higher level of national income helps in removing poverty . However it should be noted that what is produced is more important. Thus if war goods or luxury goods are produced to a greater extent , the welfare of the common man will not increase. -

Macroeconomic Circular Flow Diagram

MACROECONOMIC FLOW: CIRCULAR OR LINEAR? Edward J. O’Boyle, PhD Senior Research Associate Mayo Research Institute www.mayoresearch.org [email protected] January 2021 The macroeconomic circular-flow concept has been entrenched in economics for centuries. Haney traces the basic idea to John Law (1705), Richard Cantillon (1755) and Quesnay’s tableaux économique (1753-1758) (Haney 1949, p.126, 174 and 187f) . Sismondi addressed the same basic idea but Haney (p.393f) describes his efforts as pretentious as Quesnay’s .1 Thornton constructed the following diagram from Cantillon’s An Essay on Economic Theory (2010) on the basis of five economic agents: property owners, farmers, entrepreneurs, labor, and artisans. Source: Cantillon 2010, p.66. Fast forward to 1948 when Paul Samuelson published the first-edition of his ECONOMICS and captured the essence of the circular -flow as follows. Source: Samuelson 1948, p. 226 1 See also Backhouse and Giraud (2010) and Murphy (1993). Macroeconomic Flow: Circular or Linear? Page 2 In the simplest case, we can imagine a circular flow of dollars going from business to the public in return for productive services of labor and property; this is just matched by a flow of consumption dollars going from the public to business to pay for the purchase of real consumption goods and services (Samuelson 1948, p.226). Notice the difference between Cantillon’s thinking which centers on living, breathing economic agents whereas Samuelson’s concentrates on inanimate objects. We cite Samuelson on this matter for two reasons. First, he is a Nobel laureate. Second, the 19 th and last edition of his principles text, with William Nordhaus as co-author, was published by McGraw-Hill in 2010, meaning that he has influenced countless numbers of students of economics to think about macroeconomic affairs in circular terms. -

Circular Flow of Income and Expenditure

____________________________________________________________________________________________________ Subject ECONOMICS Paper No and Title 4, Basic Macroeconomics Module No and Title 2, Circular Flow of Income and Expenditure Module Tag ECO_P4_M2 ECONOMICS PAPER No. : 4 – Basic Macroeconomics MODULE No. : 2- Circular Flow of Income and Expenditure ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Learning Outcomes 2. Introduction 3. The Four Macroeconomic Sectors 3.1 The Household Sector 3.2 The Firms Sector 3.3 The Government Sector 3.4 The Foreign Sector 4. The Three Markets 4.1 The Goods Market 4.2 The Factor Market 4.3 The Financial Market 5. The Circular Flow of Income in a Two-Sector Model 5.1 Two-Sector Model with Saving and Investment 6. The Circular Flow of Income in a Three-Sector Model 7. The Circular Flow of Income in a Four-Sector Model 8. Leakages and Injections in the Circular Flow of Income 9. Summary ECONOMICS PAPER No. : 4 – Basic Macroeconomics MODULE No. : 2- Circular Flow of Income and Expenditure ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 1. Learning Outcomes After studying this module, you shall be able to Know the four macroeconomic sectors and the three markets. Learn the interdependence among the sectors and the markets. Identify the different models of the circular flow of income. Evaluate the leakages and injections in the circular flow. Analyse the significance of circular flow of income in macroeconomics. 2. Introduction Macroeconomics is the branch of economics that studies the economic behaviour of all the agents in the economy; i.e. it is the study of the economy as a whole. In other words, macroeconomics is the study of aggregate outcomes of the decisions taken by the different agents in an economy. -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Page 1. W hat is Economics about? 1 2. From the Cicular Flow of Income and Expenditure to Keynes 2.1. The Circular Flow in a Static Economy 2 2.2. John Maynard Keynes: Consumption - Savings - Basic Income 3 2.3. Gross Investment, Net Investment and Depreciation 6 2.4. John Maynard Keynes: Basic Income - Investment - new 7 Equilibrium Income 2.5. The Development towards the new equilibrium income 11 EXPLAINED USING THE CIRCULAR FLOW OF INCOME 2.6. The Development towards the new equilibrium income 14 EXPLAINED USING KEYNES' IDEAS 2.7. The Circular Flow of Income including Government Activities 16 2.7.1. Fiscal Multiplier or Government Spending Multiplier 17 2.7.2. Tax Multiplier 17 2.7.3. Subsidy Multiplier or Transfer Payments Multiplier 18 2.7.4. H aavelmo-Theorem 18 2.7.5. Government Activities 2.7.5.1. Government Spending 19 2.7.5.2. Transfer Payments 19 2.7.5 3. Tax Reduction 20 2.7.5.4. Tax Increase 20 2.7.5.5. Assignments 21 2.8. Criticism of Keynesian Economics 2.8.1. Deficit Spending 24 2.8.2. Time Lags 26 2.8.3. Crowding out 27 3. Macroeconomic Objectives 3.1. The German Law of Stability and Growth 28 3.2. The Magic Rectangle or the Uneasy Quadrangle 28 3.2.1. W hat is Meant by Price Stability 29 3.2.2. H igh Employment Rate 3.2.2.1. W hat is a H igh Employment Rate? 30 3.2.2.2. Types of Unemployment 32 3.2.2.3.