The Multiple Fuzzy Origins of Woodiness Within Balsaminaceae Using an Integrated Approach

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impatiens Glandulifera (Himalayan Balsam) Chloroplast Genome Sequence As a Promising Target for Populations Studies

Impatiens glandulifera (Himalayan balsam) chloroplast genome sequence as a promising target for populations studies Giovanni Cafa1, Riccardo Baroncelli2, Carol A. Ellison1 and Daisuke Kurose1 1 CABI Europe, Egham, Surrey, UK 2 University of Salamanca, Instituto Hispano-Luso de Investigaciones Agrarias (CIALE), Villamayor (Salamanca), Spain ABSTRACT Background: Himalayan balsam Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae) is a highly invasive annual species native of the Himalayas. Biocontrol of the plant using the rust fungus Puccinia komarovii var. glanduliferae is currently being implemented, but issues have arisen with matching UK weed genotypes with compatible strains of the pathogen. To support successful biocontrol, a better understanding of the host weed population, including potential sources of introductions, of Himalayan balsam is required. Methods: In this molecular study, two new complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of I. glandulifera were obtained with low coverage whole genome sequencing (genome skimming). A 125-year-old herbarium specimen (HB92) collected from the native range was sequenced and assembled and compared with a 2-year-old specimen from UK field plants (HB10). Results: The complete cp genomes were double-stranded molecules of 152,260 bp (HB92) and 152,203 bp (HB10) in length and showed 97 variable sites: 27 intragenic and 70 intergenic. The two genomes were aligned and mapped with two closely related genomes used as references. Genome skimming generates complete organellar genomes with limited technical and financial efforts and produces large datasets compared to multi-locus sequence typing. This study demonstrates the 26 July 2019 Submitted suitability of genome skimming for generating complete cp genomes of historic Accepted 12 February 2020 Published 24 March 2020 herbarium material. -

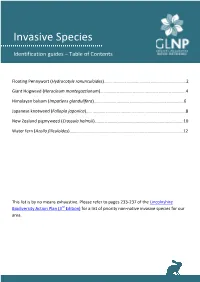

Invasive Species Identification Guide

Invasive Species Identification guides – Table of Contents Floating Pennywort (Hydrocotyle ranunculoides)……………………………….…………………………………2 Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)…………………………………………………………………….4 Himalayan balsam (Impatiens glandulifera)………………………………………………………….…………….6 Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica)………………………………………………………………………………..8 New Zealand pigmyweed (Crassula helmsii)……………………………………………………………………….10 Water fern (Azolla filiculoides)……………………………………………………………………………………………12 This list is by no means exhaustive. Please refer to pages 233-237 of the Lincolnshire Biodiversity Action Plan (3rd Edition) for a list of priority non-native invasive species for our area. Floating pennywort Hydrocotyle ranunculoides Invasive species identification guide Where is it found? Floating on the surface or emerging from still or slowly moving freshwater. Can be free floating or rooted. Similar to…… Marsh pennywort (see bottom left photo) – this has a smaller more rounded leaf that attaches to the stem in the centre rather than between two lobes. Will always be rooted and never free floating. Key features Lobed leaves Fleshy green or red stems Floating or rooted Forms dense interwoven mats Leaf Leaves can be up to 7cm in diameter. Lobed leaves can float on or stand above the water. Marsh pennywort Roots Up to 5cm Fine white Stem attaches in roots centre More rounded leaf Floating pennywort Larger lobed leaf Stem attaches between lobes Photos © GBNNSS Workstream title goes here Invasive species ID guide: Floating pennywort Management Floating pennywort is extremely difficult to control due to rapid growth rates (up to 20cm from the bank each day). Chemical control: Can use glyphosphate but plant does not rot down very quickly after treatment so vegetation should be removed after two to three weeks in flood risk areas. Regular treatment necessary throughout the growing season. -

Maine Coefficient of Conservatism

Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity Conservatism Wetness Abies balsamea balsam fir native 3 0 Abies concolor white fir non‐native 0 Abutilon theophrasti velvetleaf non‐native 0 3 Acalypha rhomboidea common threeseed mercury native 2 3 Acer ginnala Amur maple non‐native 0 Acer negundo boxelder non‐native 0 0 Acer pensylvanicum striped maple native 5 3 Acer platanoides Norway maple non‐native 0 5 Acer pseudoplatanus sycamore maple non‐native 0 Acer rubrum red maple native 2 0 Acer saccharinum silver maple native 6 ‐3 Acer saccharum sugar maple native 5 3 Acer spicatum mountain maple native 6 3 Acer x freemanii red maple x silver maple native 2 0 Achillea millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. borealis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. millefolium common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea millefolium var. occidentalis common yarrow non‐native 0 3 Achillea ptarmica sneezeweed non‐native 0 3 Acinos arvensis basil thyme non‐native 0 Aconitum napellus Venus' chariot non‐native 0 Acorus americanus sweetflag native 6 ‐5 Acorus calamus calamus native 6 ‐5 Actaea pachypoda white baneberry native 7 5 Actaea racemosa black baneberry non‐native 0 Actaea rubra red baneberry native 7 3 Actinidia arguta tara vine non‐native 0 Adiantum aleuticum Aleutian maidenhair native 9 3 Adiantum pedatum northern maidenhair native 8 3 Adlumia fungosa allegheny vine native 7 Aegopodium podagraria bishop's goutweed non‐native 0 0 Coefficient of Coefficient of Scientific Name Common Name Nativity -

Impatiens Glandulifera

NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet Impatiens glandulifera Author of this fact sheet: Harry Helmisaari, SYKE (Finnish Environment Institute), P.O. Box 140, FIN-00251 Helsinki, Finland, Phone + 358 20 490 2748, E-mail: [email protected] Bibliographical reference – how to cite this fact sheet: Helmisaari, H. (2010): NOBANIS – Invasive Alien Species Fact Sheet – Impatiens glandulifera. – From: Online Database of the European Network on Invasive Alien Species – NOBANIS www.nobanis.org, Date of access x/x/201x. Species description Scientific name: Impatiens glandulifera Royle (Balsaminaceae). Synonyms: Impatiens roylei Walpers. Common names: Himalayan balsam, Indian balsam, Policeman's Helmet (GB), Drüsiges Springkraut, Indisches Springkraut (DE), kæmpe-balsamin (DK), verev lemmalts (EE), jättipalsami (FI), risalísa (IS), bitinė sprigė (LT), puķu sprigane (LV), Reuzenbalsemien (NL), kjempespringfrø (NO), Niecierpek gruczolowaty, Niecierpek himalajski (PL), недотрога железконосная (RU), jättebalsamin (SE). Fig. 1 and 2. Impatiens glandulifera in an Alnus stand in Helsinki, Finland, and close-up of the seed capsules, photos by Terhi Ryttäri and Harry Helmisaari. Fig. 3 and 4. White and red flowers of Impatiens glandulifera, photos by Harry Helmisaari. Species identification Impatiens glandulifera is a tall annual with a smooth, usually hollow and jointed stem, which is easily broken (figs. 1-4). The stem can reach a height of 3 m and its diameter can be up to several centimetres. The leaves are opposite or in whorls of 3, glabrous, lanceolate to elliptical, 5-18 cm long and 2.5-7 cm wide. The inflorescences are racemes of 2-14 flowers that are 25-40 mm long. Flowers are zygomorphic, their lowest sepal forming a sac that ends in a straight spur. -

(Balsaminaceae) Using Chloroplast Atpb-Rbcl Spacer Sequences

Systematic Botany (2006), 31(1): pp. 171–180 ᭧ Copyright 2006 by the American Society of Plant Taxonomists Phylogenetics of Impatiens and Hydrocera (Balsaminaceae) Using Chloroplast atpB-rbcL Spacer Sequences STEVEN JANSSENS,1,4 KOEN GEUTEN,1 YONG-MING YUAN,2 YI SONG,2 PHILIPPE KU¨ PFER,2 and ERIK SMETS1,3 1Laboratory of Plant Systematics, Institute of Botany and Microbiology, Kasteelpark Arenberg 31, B-3001 Leuven, Belgium; 2Institut de Botanique, Universite´ de Neuchaˆtel, Neuchaˆtel, Switzerland; 3Nationaal Herbarium Nederland, Universiteit Leiden Branch, PO Box 9514, 2300 RA Leiden, The Netherlands 4Author for correspondence ([email protected]) ABSTRACT. Balsaminaceae are a morphologically diverse family with ca. 1,000 representatives that are mainly distributed in the Old World tropics and subtropics. To understand the relationships of its members, we obtained chloroplast atpB-rbcL sequences from 86 species of Balsaminaceae and five outgroups. Phylogenetic reconstructions using parsimony and Bayesian approaches provide a well-resolved phylogeny in which the sister group relationship between Impatiens and Hydrocera is confirmed. The overall topology of Impatiens is strongly supported and is geographically structured. Impatiens likely origi- nated in South China from which it colonized the adjacent regions and afterwards dispersed into North America, Africa, India, the Southeast Asian peninsula, and the Himalayan region. Balsaminaceae are annual or perennial herbs with in the intrageneric relationships of Impatiens. The most flowers that exhibit a remarkable diversity. The family recent molecular intrageneric study on Balsaminaceae consists of more than 1,000 species (Grey-Wilson utilized Internal Transcribed Spacer (ITS) sequences 1980a; Clifton 2000), but only two genera are recog- and provided new phylogenetic insights in Impatiens nized. -

<I>Impatiens Marroninus</I>, a New Species Of

Blumea 65, 2020: 10–11 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2020.65.01.02 Impatiens marroninus, a new species of Impatiens (Balsaminaceae) from Sumatra, Indonesia N. Utami1 Key words Abstract Impatiens marroninus Utami (Balsaminaceae), collected from Sumatra, Indonesia, is described and illustrated as a new species. The species belongs to subg. Impatiens sect. Kathetophyllon. It is characterized by Balsaminaceae opposite or whorled leaves, yellow flowers with red maroon stripes in the upper part of the two lateral petals, dark endemic green leaves and the lower sepal deeply navicular and constricted into a short curved spur. This combination of Impatiens morphological characters was previously unknown. Detailed description, illustration, phenology, IUCN conservation Indonesia assessment and ecology of the species are provided. new species taxonomy Published on 5 February 2020 INTRODUCTION TAXONOMY Balsaminaceae comprises annual or perennial herbs with flo- Impatiens marroninus Utami, sp. nov. — Fig. 1a–b, 2 wers that exhibit a remarkable diversity. The family consists of Etymology. The species epithet refers to the colour of the peduncles, two genera, the monotypic genus Hydrocera (L.) Wight & Arn. which is maroon. and Impatiens L. Hydrocera has as single species, H. triflora (L.) Wight & Arn., widely distributed in the Indo-Malaysian countries Impatiens marroninus is similar in morphology to I. beccarii Hook.f. ex ranging from India and Sri Lanka to S China (Hainan) and Indo- Dunn. In I. marroninus the leaf is dark green; lower sepal deeply navicular, constricted into a shortly curved spur; lateral petals symmetrical, yellow with nesia. On the other hand, Impatiens has over 850 species and red maroon stripes in the upper part (latter unique to Impatiens). -

World Distribution, Diversity and Endemism of Aquatic Macrophytes T ⁎ Kevin Murphya, , Andrey Efremovb, Thomas A

Aquatic Botany 158 (2019) 103127 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Aquatic Botany journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquabot World distribution, diversity and endemism of aquatic macrophytes T ⁎ Kevin Murphya, , Andrey Efremovb, Thomas A. Davidsonc, Eugenio Molina-Navarroc,1, Karina Fidanzad, Tânia Camila Crivelari Betiold, Patricia Chamberse, Julissa Tapia Grimaldoa, Sara Varandas Martinsa, Irina Springuelf, Michael Kennedyg, Roger Paulo Mormuld, Eric Dibbleh, Deborah Hofstrai, Balázs András Lukácsj, Daniel Geblerk, Lars Baastrup-Spohrl, Jonathan Urrutia-Estradam,n,o a University of Glasgow, Glasgow G12 8QQ, Scotland, United Kingdom b Omsk State Pedagogical University, 14, Tukhachevskogo nab., 644009 Omsk, Russia c Lake Group, Dept of Bioscience, Silkeborg, Aarhus University, Denmark d NUPELIA, Universidade Estadual de Maringá, Maringá, PR, Brazil e Environment and Climate Change Canada, Burlington, Ontario, Canada f Department of Botany & Environmental Science, Aswan University, 81528 Sahari, Egypt g School of Energy, Construction and Environment, University of Coventry, Priory Street, Coventry CV1 5FB, United Kingdom h Department of Wildlife, Fisheries and Aquaculture, Mississippi State University, Starkville, MS, 39762, USA i National Institute of Water and Atmospheric Research (NIWA), Hamilton, New Zealand j Department of Tisza River Research, MTA Centre for Ecological Research, DRI, 4026 Debrecen Bem tér 18/C, Hungary k Poznan University of Life Sciences, Wojska Polskiego 28, 60637 Poznan, Poland l Institute of Biology, -

How Does Genome Size Affect the Evolution of Pollen Tube Growth Rate, a Haploid Performance Trait?

Manuscript bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/462663; this version postedClick April here18, 2019. to The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv aaccess/download;Manuscript;PTGR.genome.evolution.15April20 license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 1 Effects of genome size on pollen performance 2 3 4 5 How does genome size affect the evolution of pollen tube growth rate, a haploid 6 performance trait? 7 8 9 10 11 John B. Reese1,2 and Joseph H. Williams2 12 Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of Tennessee, Knoxville, TN 13 37996, U.S.A. 14 15 16 17 1Author for correspondence: 18 John B. Reese 19 Tel: 865 974 9371 20 Email: [email protected] 21 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/462663; this version posted April 18, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license. 22 ABSTRACT 23 Premise of the Study – Male gametophytes of most seed plants deliver sperm to eggs via a 24 pollen tube. Pollen tube growth rates (PTGRs) of angiosperms are exceptionally rapid, a pattern 25 attributed to more effective haploid selection under stronger pollen competition. Paradoxically, 26 whole genome duplication (WGD) has been common in angiosperms but rare in gymnosperms. -

Comparative Genomics of the Balsaminaceae Sister Genera Hydrocera Triflora and Impatiens Pinfanensis

International Journal of Molecular Sciences Article Comparative Genomics of the Balsaminaceae Sister Genera Hydrocera triflora and Impatiens pinfanensis Zhi-Zhong Li 1,2,†, Josphat K. Saina 1,2,3,†, Andrew W. Gichira 1,2,3, Cornelius M. Kyalo 1,2,3, Qing-Feng Wang 1,3,* and Jin-Ming Chen 1,3,* ID 1 Key Laboratory of Aquatic Botany and Watershed Ecology, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] (Z.-Z.L.); [email protected] (J.K.S.); [email protected] (A.W.G.); [email protected] (C.M.K.) 2 University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China 3 Sino-African Joint Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, China * Correspondence: [email protected] (Q.-F.W.); [email protected] (J.-M.C.); Tel.: +86-27-8751-0526 (Q.-F.W.); +86-27-8761-7212 (J.-M.C.) † These authors contributed equally to this work. Received: 21 December 2017; Accepted: 15 January 2018; Published: 22 January 2018 Abstract: The family Balsaminaceae, which consists of the economically important genus Impatiens and the monotypic genus Hydrocera, lacks a reported or published complete chloroplast genome sequence. Therefore, chloroplast genome sequences of the two sister genera are significant to give insight into the phylogenetic position and understanding the evolution of the Balsaminaceae family among the Ericales. In this study, complete chloroplast (cp) genomes of Impatiens pinfanensis and Hydrocera triflora were characterized and assembled using a high-throughput sequencing method. The complete cp genomes were found to possess the typical quadripartite structure of land plants chloroplast genomes with double-stranded molecules of 154,189 bp (Impatiens pinfanensis) and 152,238 bp (Hydrocera triflora) in length. -

Description of a New Species and Lectotypification of Two Names In

plants Article Description of a New Species and Lectotypification of Two Names in Impatiens Sect. Racemosae (Balsaminaceae) from China Shuai Peng 1,2,3 , Peninah Cheptoo Rono 1,2,3, Jia-Xin Yang 1,2,3, Jun-Jie Wang 1,2,3, Guang-Wan Hu 1,2,* and Qing-Feng Wang 1,2 1 CAS Key Laboratory of Plant Germplasm Enhancement and Specialty Agriculture, Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, China; [email protected] (S.P.); [email protected] (P.C.R.); [email protected] (J.-X.Y.); [email protected] (J.-J.W.); [email protected] (Q.-F.W.) 2 Sino-Africa Joint Research Center, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Wuhan 430074, China 3 Wuhan Botanical Garden, Chinese Academy of Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100049, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-027-8751-1510 Abstract: Impatiens longiaristata (Balsaminaceae), a new species from western Sichuan Province in China, is described and illustrated here based on morphological and molecular data. It is similar to I. longiloba and I. siculifer, but differs in its lower sepal with a long arista at the apex of the mouth, spur curved downward or circinate, and lower petal that is oblong-elliptic and two times longer than the upper petal. Molecular analysis confirmed its placement in sect. Racemosae. Simultaneously, during the inspection of the protologues and type specimens of allied species, it was found that the types of two names from this section were syntypes based on Article 9.6 of the International Code Citation: Peng, S.; Rono, P.C.; Yang, J.-X.; Wang, J.-J.; Hu, G.-W.; Wang, of Nomenclature for algae, fungi, and plants (Shenzhen Code). -

Is the Spread of Non-Native Plants in Alaska Accelerating?

Meeting the Challenge: Invasive Plants in Pacific Northwest Ecosystems IS THE SPREAD OF NON-NATIVE PLANTS IN ALASKA ACCELERATING? Matthew L. Carlson1 and Michael Shephard2 ABSTRACT Alaska has remained relatively unaffected by non-native plants; however, recently the state has started to experience an influx of invasive non-native plants that the rest of the U.S. underwent 60–100 years ago. With the increase in population, gardening, development, and commerce there have been more frequent introductions to Alaska. Many of these species, such as meadow hawkweed (Hieracium caespitosum), Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense), and spotted knapweed (Centaurea biebersteinii), have only localized populations in Alaska. Other species such as reed canary grass (Phalaris arundinacea) and white sweetclover (Melilotus officinalis), both formerly used in roadside seed mixes, are now very widespread and are moving into riparian areas and wetlands. We review the available literature and Alaska’s statewide invasive plant database (AKEPIC, Alaska Exotic Plant Clearinghouse) to summarize changes in Alaska’s non-native flora over the last 65 years. We suggest that Alaska is not immune to invasion, but rather that the exponential increase in non-native plants experienced else- where is delayed by a half century. This review highlights the need for more intensive detection and rapid response work if Alaska is going to remain free of many of the invasive species problems that plague the contiguous U.S. KEYWORDS: Alaska, invasion patterns, invasive plants, non-native plants, plant databases. INTRODUCTION presence of non-native plants. Recently, however, popula- Most botanists and ecologists thought Alaska was immune tions of many non-native species appear to be expanding to the invasion of non-native plants the rest of the United and most troubling, a number of species are spreading into States had experienced, and continue to experience, given natural habitats. -

Eugene District Aquatic and Riparian Restoration Activities

Environmental Assessment for Eugene District Aquatic and Riparian Restoration Activities Environmental Assessment # DOI-BLM-OR-090-2009-0009-EA U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT EUGENE DISTRICT 2010 U.S. Department of the Interior, Bureau of Land Management Eugene District Office 3106 Pierce Parkway, Suite E Eugene, Oregon 97477 Before including your address, phone number, e-mail address, or other personal identifying information in your comment, be advised that your entire comment –including your personal identifying information –may be made publicly available at any time. While you can ask us in your comment to withhold from public review your personal identifying information, we cannot guarantee that we will be able to do so. In keeping with Bureau of Land Management policy, the Eugene District posts Environmental Assessments, Findings of No Significant Impact, and Decision Records on the district web page under Plans & Projects at www.blm.gov/or/districts/eugene. Individuals desiring a paper copy of such documents will be provided one upon request. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER ONE - PURPOSE AND NEED FOR ACTION I. Introduction .......................................................................................................4 II. Purpose and Need for Action ............................................................................4 III. Conformance .....................................................................................................5 IV. Issues for Analysis ............................................................................................8