Seafood Watch Seafood Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard (2012)

FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard Marine and Coastal Spatial Data Subcommittee Federal Geographic Data Committee June, 2012 Federal Geographic Data Committee FGDC-STD-018-2012 Coastal and Marine Ecological Classification Standard, June 2012 ______________________________________________________________________________________ CONTENTS PAGE 1. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Objectives ................................................................................................................ 1 1.2 Need ......................................................................................................................... 2 1.3 Scope ........................................................................................................................ 2 1.4 Application ............................................................................................................... 3 1.5 Relationship to Previous FGDC Standards .............................................................. 4 1.6 Development Procedures ......................................................................................... 5 1.7 Guiding Principles ................................................................................................... 7 1.7.1 Build a Scientifically Sound Ecological Classification .................................... 7 1.7.2 Meet the Needs of a Wide Range of Users ...................................................... -

Fishery Resources Reading: Chapter 3 Invertebrate and Vertebrate Fisheries Diversity and Life History Species Important Globally Species Important Locally

Exploited Fishery Resources Reading: Chapter 3 Invertebrate and vertebrate fisheries Diversity and life history species important globally species important locally Fisheries involving Invertebrate Phyla Mollusca • Bivalves, Gastropods and Cephalopods Echinodermata • sea cucumbers and urchins Arthropoda • Sub-phylum Crustacea: • shrimps and prawns • clawed lobsters, crayfish • clawless lobsters • crabs Phylum Mollusca: Bivalves Fisheries • Oysters, Scallops, Mussels, and Clams • World catch > 1 million MT • Ideal for aquaculture (mariculture) • Comm. and rec. in shallow water 1 Phylum Mollusca: Gastropods Fisheries • Snails, whelks, abalone • Largest number of species • Most harvested from coastal areas • Food & ornamental shell trade • Depletion of stocks (e.g. abalone) due to habitat destruction & overexploitation Phylum Mollusca: Cephalopods Fisheries • Squid, octopus, nautilus • 70% of world mollusc catch = squids • Inshore squid caught with baited jigs, purse seines, & trawls • Oceanic: gill nets & jigging Phylum Echinodermata Fisheries • Sea cucumbers and sea urchins Sea cucumber fisheries • Indian & Pacific oceans, cultured in Japan • slow growth rates, difficult to sustain Sea urchin fisheries • roe (gonads) a delicacy • seasonal based on roe availability Both Easily Overexploited 2 Sub-phylum Crustacea: Shrimps & Prawns Prawn fisheries • extensive farming (high growth rate & fecundity) • Penaeids with high commercial value • stocks in Australia have collapsed due to overfishing & destruction of inshore nursery areas Caridean -

(Slide 1) Lesson 3: Seafood-Borne Illnesses and Risks from Eating

Introductory Slide (slide 1) Lesson 3: Seafood-borne Illnesses and Risks from Eating Seafood (slide 2) Lesson 3 Goals (slide 3) The goal of lesson 3 is to gain a better understanding of the potential health risks of eating seafood. Lesson 3 covers a broad range of topics. Health risks associated specifically with seafood consumption include bacterial illness associated with eating raw seafood, particularly raw molluscan shellfish, natural marine toxins, and mercury contamination. Risks associated with seafood as well as other foods include microorganisms, allergens, and environmental contaminants (e.g., PCBs). A section on carotenoid pigments (“color added”) explains the use of these essential nutrients in fish feed for particular species. Dyes are not used by the seafood industry and color is not added to fish—a common misperception among the public. The lesson concludes with a discussion on seafood safety inspection, country of origin labeling (COOL) requirements, and a summary. • Lesson 3 Objectives (slide 4) The objectives of lesson 3 are to increase your knowledge of the potential health risks of seafood consumption, to provide context about the potential risks, and to inform you about seafood safety inspection programs and country of origin labeling for seafood required by U.S. law. Before we begin, I would like you to take a few minutes to complete the pretest. Instructor: Pass out lesson 3 pretest. Foodborne Illnesses (slide 5) Although many people are complacent about foodborne illnesses (old risk, known to science, natural, usually not fatal, and perceived as controllable), the risk is serious. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates 48 million people suffer from foodborne illnesses annually, resulting in about 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths. -

Fishes of Hawaii: Life in the Sand Fishinar 11/14/16 Dr

Fishes of Hawaii: Life in the Sand Fishinar 11/14/16 Dr. Christy Pattengill-Semmens, Ph.D.– Instructor Questions? Feel free to contact me at Director of Science- REEF [email protected] Hawaiian Garden Eel (Gorgasia hawaiiensis) – Conger Eel Light grayish green, covered in small brownish spots. Found in colonies, feeding on plankton. Only garden eel in Hawaii. Up to 24” ENDEMIC Photo by: John Hoover Two-Spot Sandgoby (Fusigobius duospilus) – Goby Small translucent fish with many orangish-brown markings on body. Black dash markings on first dorsal (looks like vertical dark line). Small blotch at base of tail (smaller than pupil). Pointed nose. The only sandgoby in Hawaii. Photo by: John Hoover Eyebar Goby (Gnatholepis anjerensis) - Goby Thin lines through eye that do not meet at the top of the head. Row of smudgy spots down side of body. Small white spots along base of dorsal fin. Can have faint orange shoulder spot. Typically shallow, above 40 ft. Up to 3” Photo by: Christa Rohrbach Shoulder-spot Goby (Gnatholepis cauerensis) - Goby aka Shoulderbar Goby in CIP and SOP Line through eye is typically thicker, and it goes all the way across its head. Body has numerous thin lines made up of small spots. Small orange shoulder spot usually visible and is vertically elongated. Typically deeper, below 40 ft. Up to 3” Photo by: Florent Charpin Hawaiian Shrimpgoby (Psilogobius mainlandi) - Goby Found in silty sand, lives commensally with a blind shrimp. Pale body color with several vertical pale thin lines, can have brownish orange spots. Eyes can be very dark. -

Calypso LNG Deepwater Port Project, Florida: Marine Benthic Video Survey Charles Messing Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, [email protected]

Nova Southeastern University NSUWorks Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Reports Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences 6-12-2006 Calypso LNG Deepwater Port Project, Florida: Marine Benthic Video Survey Charles Messing Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, [email protected] Brian K. Walker Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, [email protected] Richard E. Dodge Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, [email protected] John K. Reed Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution Sandra Brooke Florida Fish and Wildlife Research Institute Find out more information about Nova Southeastern University and the Halmos College of Natural Sciences and Oceanography. Follow this and additional works at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facreports Part of the Marine Biology Commons, and the Oceanography and Atmospheric Sciences and Meteorology Commons NSUWorks Citation Charles Messing, Brian K. Walker, Richard E. Dodge, John K. Reed, and Sandra Brooke. 2006. Calypso LNG Deepwater Port Project, Florida: Marine Benthic Video Survey : 1 -61. https://nsuworks.nova.edu/occ_facreports/77. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Marine and Environmental Sciences at NSUWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Marine & Environmental Sciences Faculty Reports by an authorized administrator of NSUWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Calypso LNG Deepwater Port Project, Florida Marine Benthic Video Survey FINAL REPORT 12 June 2006 Submitted to: Ecology and Environment, Inc. & SUEZ Energy North America, Inc. Submitted by: Charles G. Messing, Ph.D., Brian K. Walker, M.S. and Richard E. Dodge, Ph.D. National Coral Reef Institute, Nova Southeastern University Oceanographic Center, 8000 North Ocean Drive, Dania Beach, FL 33004 John Reed, M.S., Harbor Branch Oceanographic Institution 5600 U.S. -

Rubble Mounds of Sand Tilefish Mala Canthus Plumieri (Bloch, 1787) and Associated Fishes in Colombia

BULLETIN OF MARINE SCIENCE, 58(1): 248-260, 1996 CORAL REEF PAPER RUBBLE MOUNDS OF SAND TILEFISH MALA CANTHUS PLUMIERI (BLOCH, 1787) AND ASSOCIATED FISHES IN COLOMBIA Heike Buttner ABSTRACT A 6-month study consisting of collections and observations revealed that a diverse fauna of reef-fishes inhabit the rubble mounds constructed by the sand tilefish Malacanthus plumieri (Perciformes: Malacanthidae), In the Santa Marta region, on the Caribbean coast of Colombia, M, plumieri occurs on sandy areas just beyond the coral zone. The population density is correlated with the geomorphology of the bays; the composition of the material utilized depends on its availability. Experiments showed that debris was distributed over a distance of 35 m. Hard substrate must be excavated to reach their caves. In the area around Santa Marta the sponge Xestospongia muta was often used by the fish as a visual signal for suitable substratum. The rubble mounds represent a secondary structure within the "coral reef" eco- system. These substrate accumulations create structured habitats in the fore reef, which arc distributed like islands in the monotonous sandy environment and where numerous benthic organisms are concentrated. The tilefish nests attract other organisms because they provide shelter and a feeding site in an area where they would not normally be found. At least 32 species of fishes were found to be associated with the mounds. Some species lived there exclusively during their juvenile stage, indicating that the Malacanthus nests serve as a nursery-habitat. M. plumieri plays an important role in the diversification of the reef envi- ronment. For several years artificial reefs and isolated structures, for example patch reefs and coral blocks, have been the subject of investigations of development and dynamics of benthic communities (Randall, 1963; Fager, 1971; Russell, 1975; Russell et aI., 1974; Sale and Dybdahl, 1975). -

Checklist of Marine Demersal Fishes Captured by the Pair Trawl Fisheries in Southern (RJ-SC) Brazil

Biota Neotropica 19(1): e20170432, 2019 www.scielo.br/bn ISSN 1676-0611 (online edition) Inventory Checklist of marine demersal fishes captured by the pair trawl fisheries in Southern (RJ-SC) Brazil Matheus Marcos Rotundo1,2,3,4 , Evandro Severino-Rodrigues2, Walter Barrella4,5, Miguel Petrere Jun- ior3 & Milena Ramires4,5 1Universidade Santa Cecilia, Acervo Zoológico, R. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, CEP11045-907, Santos, SP, Brasil 2Instituto de Pesca, Programa de Pós-graduação em Aquicultura e Pesca, Santos, SP, Brasil 3Universidade Federal de São Carlos, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Planejamento e Uso de Recursos Renováveis, Rodovia João Leme dos Santos, Km 110, CEP 18052-780, Sorocaba, SP, Brasil 4Universidade Santa Cecília, Programa de Pós-Graduação de Auditoria Ambiental, R. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, CEP11045-907, Santos, SP, Brasil 5Universidade Santa Cecília, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Sustentabilidade de Ecossistemas Costeiros e Marinhos, R. Oswaldo Cruz, 266, CEP11045-907, Santos, SP, Brasil *Corresponding author: Matheus Marcos Rotundo: [email protected] ROTUNDO, M.M., SEVERINO-RODRIGUES, E., BARRELLA, W., PETRERE JUNIOR, M., RAMIRES, M. Checklist of marine demersal fishes captured by the pair trawl fisheries in Southern (RJ-SC) Brazil. Biota Neotropica. 19(1): e20170432. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1676-0611-BN-2017-0432 Abstract: Demersal fishery resources are abundant on continental shelves, on the tropical and subtropical coasts, making up a significant part of the marine environment. Marine demersal fishery resources are captured by various fishing methods, often unsustainably, which has led to the depletion of their stocks. In order to inventory the marine demersal ichthyofauna on the Southern Brazilian coast, as well as their conservation status and distribution, this study analyzed the composition and frequency of occurrence of fish captured by pair trawling in 117 fishery fleet landings based in the State of São Paulo between 2005 and 2012. -

Poster Presentations Anthropogenic Impacts Interacting Influence of Low

Poster Presentations Anthropogenic Impacts Interacting influence of low salinity and nutrient pulses on the growth of bloom-forming Ulva compressa Guidone, M.; Steele, L. Sacred Heart University, Fairfield, CT 06825. [email protected] For the eastern US, it is predicted that climate change will increase the frequency of severe rainstorms, inundating coastal areas with pulses of freshwater that will reduce salinity but also temparily increase nutrients through sewage overflow and storm runoff. In an effort to predict how this may influence the frequency and severity of macroalgal blooms, this study examined the interacting effect of salinity and nutrient supply on bloom-forming Ulva compressa. In laboratory experiments with constant nutrient supply, U. compressa showed decreased growth at low salinities; however, this decrease was not detectable until the fifth day of treatment. Moreover, U. compressa demonstrated an extraordinary tolerance for freshwater, surviving for 48 hours without nutrients at 0 PSU. When exposed to pulses of freshwater (0 PSU) and varying nutrient levels (none, low, high) lasting either 0.5, 4, or 8 hours, U. compressa growth was negatively impacted in the treatment without nutrients and positively impacted by the low and high nutrient treatments. Furthermore, thalli in the high nutrient treatment showed increased growth with increased pulse time. These findings, combined with observations of U. compressa’s tolerance for high temperatures, suggest Ulva blooms will not decrease in frequency or severity with a change in precipitation patterns. Additional information: a) Faculty b) Poster c) Anthropogenic impacts; Community ecology d) No Long Term Effects of Anthropogenic Influences on Marine Benthic Macrofauna Adjacent to McMurdo Station, Antarctica Smith, S.1; Montagna, P.; Palmer, T.; Hyde, L. -

Sedar50-Rd30

Stock Complexes for Fisheries Management in the Gulf of Mexico Nicholas A. Farmer, Richard P. Malinowski, Mary F. McGovern, and Peter J. Rubec SEDAR50-RD30 22 July 2016 Marine and Coastal Fisheries Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science ISSN: (Print) 1942-5120 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/umcf20 Stock Complexes for Fisheries Management in the Gulf of Mexico Nicholas A. Farmer, Richard P. Malinowski, Mary F. McGovern & Peter J. Rubec To cite this article: Nicholas A. Farmer, Richard P. Malinowski, Mary F. McGovern & Peter J. Rubec (2016) Stock Complexes for Fisheries Management in the Gulf of Mexico, Marine and Coastal Fisheries, 8:1, 177-201, DOI: 10.1080/19425120.2015.1024359 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/19425120.2015.1024359 Published with license by the American Fisheries Society© Nicholas A. Farmer, Richard P. Malinowski, Mary F. McGovern, and Peter J. Rubec Published online: 26 May 2016. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 379 View related articles View Crossmark data Citing articles: 1 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=umcf20 Download by: [216.215.241.165] Date: 22 July 2016, At: 08:08 Marine and Coastal Fisheries: Dynamics, Management, and Ecosystem Science 8:177–201, 2016 Published with license by the American Fisheries Society ISSN: 1942-5120 online DOI: 10.1080/19425120.2015.1024359 SPECIAL SECTION: SPATIAL ANALYSIS, MAPPING, AND MANAGEMENT OF MARINE FISHERIES Stock Complexes for Fisheries Management in the Gulf of Mexico Nicholas A. Farmer* and Richard P. -

Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations Biological Sciences Summer 2016 Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes Christi Linardich Old Dominion University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds Part of the Biodiversity Commons, Biology Commons, Environmental Health and Protection Commons, and the Marine Biology Commons Recommended Citation Linardich, Christi. "Hotspots, Extinction Risk and Conservation Priorities of Greater Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico Marine Bony Shorefishes" (2016). Master of Science (MS), Thesis, Biological Sciences, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/hydh-jp82 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/biology_etds/13 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Biological Sciences at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Biological Sciences Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOTSPOTS, EXTINCTION RISK AND CONSERVATION PRIORITIES OF GREATER CARIBBEAN AND GULF OF MEXICO MARINE BONY SHOREFISHES by Christi Linardich B.A. December 2006, Florida Gulf Coast University A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE BIOLOGY OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY August 2016 Approved by: Kent E. Carpenter (Advisor) Beth Polidoro (Member) Holly Gaff (Member) ABSTRACT HOTSPOTS, EXTINCTION RISK AND CONSERVATION PRIORITIES OF GREATER CARIBBEAN AND GULF OF MEXICO MARINE BONY SHOREFISHES Christi Linardich Old Dominion University, 2016 Advisor: Dr. Kent E. Carpenter Understanding the status of species is important for allocation of resources to redress biodiversity loss. -

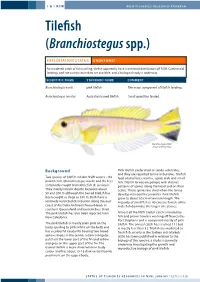

Tilefish (Branchiostegus Spp.)

I & I NSW WILD FISHERIES RESEARCH PROGRAM Tilefish (Branchiostegus spp.) EXPLOITATION STATUS UNDEFINED An incidental catch of fish trawling, tilefish apparently have a restricted distribution off NSW. Commercial landings and size composition data are available, and a biological study is underway. SCIENTIFIC NAME STANDARD NAME COMMENT Branchiostegus wardi pink tilefish The major component of tilefish landings. Branchiostegus serratus Australian barred tilefish Small quantities landed. Branchiostegus wardi Image © Bernard Yau Background Pink tilefish prefer mud or sandy substrates, and they are reported to live in burrows. Tilefish Two species of tilefish inhabit NSW waters - the feed on molluscs, worms, squid, crab and small pink tilefish, (Branchiostegus wardi) and the less fish. Tilefish larvae are pelagic with distinct commonly caught barred tilefish (B. serratus). patterns of spines along the head and on their They mainly inhabit depths between about scales. These spines are shed when the larvae 50 and 200 m although the barred tilefish has develop into benthic juveniles. Pink tilefish been caught as deep as 350 m. Both have a grow to about 50 cm maximum length. The relatively restricted distribution along the east majority of small fish (< 40 cm) are female while coast of Australia, between Noosa Heads in male fish dominate the larger size classes. southern Queensland and eastern Bass Strait. The pink tilefish has also been reported from Almost all the NSW tilefish catch is landed by New Caledonia. fish and prawn trawlers working off Newcastle- Port Stephens and is comprised mostly of pink The pink tilefish is mainly plain pink on the tilefish. The annual catch has reached 11 t but body, grading to pink/white on the belly and is mostly less than 5 t. -

1 Updated Through January 27, 2016 NOTE: the FOLLOWING IS an UNOFFICIAL COMPILATION of FEDERAL REGULATIONS PREPARED in the SOUTH

Updated through January 27, 2016 NOTE: THE FOLLOWING IS AN UNOFFICIAL COMPILATION OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS PREPARED IN THE SOUTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE OF THE NATIONAL MARINE FISHERIES SERVICE FOR THE INFORMATION AND CONVENIENCE OF INTERESTED PERSONS. IT DOES NOT INCLUDE CHANGES TO THESE REGULATIONS THAT MAY HAVE OCCURRED AFTER THE DATE INDICATED ABOVE. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) 50 CFR Part 622 PART 622--FISHERIES OF THE CARIBBEAN, GULF OF MEXICO, AND SOUTH ATLANTIC TABLE OF CONTENTS Subpart A--General Provisions.................................. 8 § 622.1 Purpose and scope. ................................... 8 § 622.2 Definitions and acronyms ............................ 10 § 622.3 Relation to other laws and regulations .............. 20 § 622.4 Permits and fees--general ........................... 21 § 622.5 Recordkeeping and reporting--general ................ 25 § 622.6 Vessel identification ............................... 27 § 622.7 Fishing years ....................................... 28 § 622.8 Quotas--general ..................................... 29 § 622.9 Prohibited gear and methods--general ................ 30 § 622.10 Landing fish intact--general ....................... 31 § 622.11 Bag and possession limits--general applicability ... 32 § 622.12 Annual catch limits (ACLs) and accountability measures (AMs) for Caribbean island management areas/Caribbean EEZ ... 32 § 622.13 Prohibitions--general .............................. 35 § 622.14