Protecting and Enhancing Acton, Edleston and Henhull's Natural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

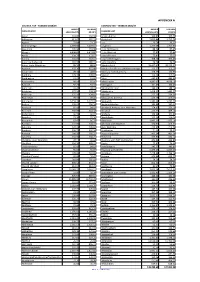

Counciltaxbase201819appendix , Item 47

APPENDIX A COUNCIL TAX - TAXBASE 2018/19 COUNCIL TAX - TAXBASE 2018/19 BAND D TAX BASE BAND D TAX BASE CHESHIRE EAST EQUIVALENTS 99.00% CHESHIRE EAST EQUIVALENTS 99.00% Acton 163.82 162.18 Kettleshulme 166.87 165.20 Adlington 613.67 607.53 Knutsford 5,813.84 5,755.70 Agden 72.04 71.32 Lea 20.78 20.57 Alderley Edge 2,699.00 2,672.01 Leighton 1,770.68 1,752.97 Alpraham 195.94 193.98 Little Bollington 88.34 87.45 Alsager 4,498.81 4,453.82 Little Warford 37.82 37.44 Arclid 154.71 153.17 Lower Peover 75.81 75.05 Ashley 164.05 162.41 Lower Withington 308.54 305.45 Aston by Budworth 181.97 180.15 Lyme Handley 74.74 74.00 Aston-juxta-Mondrum 89.56 88.66 Macclesfield 18,407.42 18,223.35 Audlem 937.36 927.98 Macclesfield Forest/Wildboarclough 112.25 111.13 Austerson 49.34 48.85 Marbury-cum-Quoisley 128.25 126.97 Baddiley 129.37 128.07 Marton 113.19 112.06 Baddington 61.63 61.02 Mere 445.42 440.96 Barthomley 98.14 97.16 Middlewich 4,887.05 4,838.18 Basford 92.23 91.31 Millington 101.43 100.42 Batherton 24.47 24.23 Minshull Vernon 149.65 148.16 Betchton 277.16 274.39 Mobberley 1,458.35 1,443.77 Bickerton 125.31 124.05 Moston 277.53 274.76 Blakenhall 70.16 69.46 Mottram St Andrew 416.18 412.02 Bollington 3,159.33 3,127.74 Nantwich 5,345.68 5,292.23 Bosley 208.63 206.54 Nether Alderley 386.48 382.61 Bradwall 85.68 84.82 Newbold Astbury-cum-Moreton 374.85 371.10 Brereton 650.89 644.38 Newhall 413.32 409.18 Bridgemere 66.74 66.07 Norbury 104.94 103.89 Brindley 73.30 72.56 North Rode 125.29 124.04 Broomhall 87.47 86.59 Odd Rode 1,995.13 1,975.18 Buerton -

W.Y.B. Canal Fishing.Ppp

W.Y.B. Canal Fishing (Wybunbury Anglers Association) Over 12 miles of Canal fishing around Nantwich, Cheshire. £12 (plus £1 postage) gives unlimited fishing up to 31st March 2021 Juniors under age 16, fish for free. Email to [email protected] or phone 07504 346 883. Four areas included :- 1. ‘The Shroppie’ - Coole Pilate ,Bridge 80 to Hack Green 86. 2. ‘The Shroppie’ - Nantwich to Beeston - Bridges 93 to 107. 3. ‘The Shroppie’ - Adderley to Audlem - Bridges 69 to 76. 4. ‘Welsh’ Canal - Burland to Stoneley Green - Bridges 6 to 10. 1. Coole Pilate CW5 8AU has plentiful roadside parking, with two access points : one via steps, the other by slope complete with handrail. Also at Hack Green, CW5 8AL (2.1 miles) 2. The Shroppie between Nantwich and Beeston offers over 7 miles of fishing with multiple access points, including :- Acton CW5 8LG - best accessed from Henhull. Henhull CW5 6AG - good adjacent parking for several vehicles. Barbridge (East) CW5 6BH - adjacent parking for several vehicles. Barbridge (West) CW5 6BG - space for two cars. Wardle - Busy main road. Park on bridge by roundabout. Good slope access. Wardle (West) CW6 9JW - parking available at J.S.Bailey Ltd in return for use of Cafe or Shop - available 8am to 5pm Monday to Friday. Saturday 8.30am to 4pm. Closed on some Sundays in Winter. NB. Access is locked at other times. Calveley CW6 9JL - Parking yet to be confirmed. Use J.S. Bailey Ltd. Tilstone CW6 9QH - roadside at own risk, due to narrow road. Bunbury CW6 9QB - roadside parking by canal bridge. -

Index of Cheshire Place-Names

INDEX OF CHESHIRE PLACE-NAMES Acton, 12 Bowdon, 14 Adlington, 7 Bradford, 12 Alcumlow, 9 Bradley, 12 Alderley, 3, 9 Bradwall, 14 Aldersey, 10 Bramhall, 14 Aldford, 1,2, 12, 21 Bredbury, 12 Alpraham, 9 Brereton, 14 Alsager, 10 Bridgemere, 14 Altrincham, 7 Bridge Traffbrd, 16 n Alvanley, 10 Brindley, 14 Alvaston, 10 Brinnington, 7 Anderton, 9 Broadbottom, 14 Antrobus, 21 Bromborough, 14 Appleton, 12 Broomhall, 14 Arden, 12 Bruera, 21 Arley, 12 Bucklow, 12 Arrowe, 3 19 Budworth, 10 Ashton, 12 Buerton, 12 Astbury, 13 Buglawton, II n Astle, 13 Bulkeley, 14 Aston, 13 Bunbury, 10, 21 Audlem, 5 Burton, 12 Austerson, 10 Burwardsley, 10 Butley, 10 By ley, 10 Bache, 11 Backford, 13 Baddiley, 10 Caldecote, 14 Baddington, 7 Caldy, 17 Baguley, 10 Calveley, 14 Balderton, 9 Capenhurst, 14 Barnshaw, 10 Garden, 14 Barnston, 10 Carrington, 7 Barnton, 7 Cattenhall, 10 Barrow, 11 Caughall, 14 Barthomley, 9 Chadkirk, 21 Bartington, 7 Cheadle, 3, 21 Barton, 12 Checkley, 10 Batherton, 9 Chelford, 10 Bebington, 7 Chester, 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 16, 17, Beeston, 13 19,21 Bexton, 10 Cheveley, 10 Bickerton, 14 Chidlow, 10 Bickley, 10 Childer Thornton, 13/; Bidston, 10 Cholmondeley, 9 Birkenhead, 14, 19 Cholmondeston, 10 Blackden, 14 Chorley, 12 Blacon, 14 Chorlton, 12 Blakenhall, 14 Chowley, 10 Bollington, 9 Christleton, 3, 6 Bosden, 10 Church Hulme, 21 Bosley, 10 Church Shocklach, 16 n Bostock, 10 Churton, 12 Bough ton, 12 Claughton, 19 171 172 INDEX OF CHESHIRE PLACE-NAMES Claverton, 14 Godley, 10 Clayhanger, 14 Golborne, 14 Clifton, 12 Gore, 11 Clive, 11 Grafton, -

Wrightmarshall.Co.Uk Fineandcountry.Com

3 SWAN CLOSE | EDLESTON | NANTWICH | CHESHIRE | CW5 5XE | OIRO £285,000 COUNTRY HOMES │ COTTAGES │ UNIQUE PROPERTIES │ CONVERSIONS │ PERIOD PROPERTIES │ LUXURY APARTMENTS wrightmarshall.co.uk fineandcountry.com 3 Swan Close, Edleston, Nantwich, Cheshire, CW5 5XE OUTSTANDING UNRIVALLED CANAL ASPECT IN A SOUGHT AFTER EDGE OF TOWN POSITION An incredibly charming Detached double fronted house of considerable appeal. Built just 5 years ago, the outstanding home is beautifully presented in a characterful cottage style with meticulous accommodation, walled corner plot gardens with recently built oak veranda, tandem drive & an unrivalled canal outlook. The exacting accommodation briefly comprises; Pretty Canopy Porch, Entrance Hall, Utility/WC, Living Room with superb canal view, Kitchen Diner with French doors to the garden & pleasant front aspect. First Floor Landing, Bedroom One (enlarged utilising the original Bedroom Three, Bedroom Two & Ensuite Shower Room, Family Bathroom. Single Garage & Tarmacadam tandem driveway with space for approx three vehicles. Enchanting cottage style gardens to the front & side being richly planted with specimen Roses, Olive trees & other herbaceous plants. Rear walled courtyard style garden of immense appeal with simulated grass, seating/entertaining are beneath a stunning solid oak veranda. UPVC D.G. & Gas C.H. DIRECTIONS WELSH ROW From the Agent's Nantwich office in the High Street, proceed along No 3 Swan Close is within walking distance of open countryside & the Hospital Street. At the mini roundabout, take the 2nd exit & continue Shropshire Union Canal. Highly regarded Malbank School & 6th Form past Morrisons Supermarket on your right hand side. At the next College is a few hundred yards from the property. -

Schools Admission Booklets

2020/21 Applying for School Places 1 Apply online at www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/schooladmissions Apply online for a school place It’s quick and easy You can apply from 1st September 2019 at www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/ schooladmissions Applications should be submitted by 31st October 2019 for secondary 15th January 2020 for primary If you are a parent resident in Cheshire East, with a child born between 1 September 2015 and 31 August 2016, your child will be due to start primary school in September 2020. If you do not have web access call 0300 123 5012 Late applications may be disadvantaged 2 Apply online at www.cheshireeast.gov.uk/schooladmissions Councillor Dorothy Flude Jacky Forster Children and Families Portfolio Director of Education Holder and 14-19 Skills Dear Parents Parents are also asked to think about how their child Your son or daughter will soon be approaching the will travel to school when making their preferences. important milestone where you need to consider Cheshire East is committed to working with schools and apply for a school place to either start in to encourage pupils to walk, cycle, use public reception at primary school or start at secondary transport or car share where possible to minimise school in September 2020. We appreciate this is the impact on the environment and as part of a really important decision for you and your son/ healthy lifestyles for Cheshire East pupils. daughter. If your son or daughter has an Education, Health This booklet aims to provide you with information and Care Plan, the SEND Statutory Assessment about schools and/or signpost you to information and Monitoring Service will work with you to identify in order to support you in identifying your preferred the nearest suitable school which can meet your schools and to advise you on the process of applying child’s needs. -

CHESHIRE. (KELLY's Mondeley P.C

18 .AC'fON. CHESHIRE. (KELLY's mondeley P.C. is lord of the manm and chief landowner. area is 509 acres; rateable value, £r,283; the population • Edleston Hall is now occupied as a farmhouse. The m 1901 was 102. ~rea is 640 a<:res; rateable vaJ.ue, .£r,645; the population ;:\.cton, half a mile distant, is the nearest money order & m rgor was 74· telegraph office F.ADDILEY is a township, 3~ miles west from Acton HURLESTON, 2:f miles north-west from Nantwich, is and 4~ west from Nantwich station on the Crewe and a township and scattered village, on the road.Jrom Xant Shrewsbury soction of the London and North ·western wich tG Chester. The Shmpshire Union canal passes railway. Woodhey chapel, built and endowed with £25 through. Henry J. Tollemache es!]_. M.P. is lord of thfl yearly by Lady Wilbraham about qoo, is a small edifice manor and the prindpal landowner. The area. is 1,376 ()f brick with stone dressings. The living is a perpetual acres; rateable vaJlue, £2,599 ; the population in 1901 ..curacy, gross yearly value .£2o, in the gift of Lord was 23. Tollemache, and held since 1892 by the Rev. Jermyn Shephard Hirst B ..A. of Que~m's College, Cambridge; and .Act on, one mile distant, is the n~rest money order & :roctor of Baddiley, where he resides. Woodhey Hall, for telegraph office several centuries the residence of a branch of the Wil- STOKE is a township, 3! miles north-west from Nant- braham family, is now oocupied as a farmhouse. -

13/2035N Location: Land at the Former Wardle

Application No: 13/2035N Location: Land at the former Wardle Airfield, Wardle, Nantwich, Cheshire Proposal: Outline Planning Application Including Means of Access for Employment Development Comprising Light Industry, General Industrial and Storage and Distribution Uses (B1(C)/B2/B8 Use Classes) on Land at the Former Wardle Airfield, Cheshire - ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: PLEASE SEE ADDENDUM TO THE ENVIRONMENTAL STATEMENT. Applicant: PHILLIP POSNETT, HAUGHTON ESTATE Expiry Date: 09-Sep-2013 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION Approve with conditions MAIN ISSUES Impact of the development on:- - Principal of the development - Highway implications - Sustainability of the site - Amenity - Design - Landscape - Trees and Hedgerows - Ecology - Flood Risk & Drainage - Impact upon Listed Buildings and the Heritage of the Site - Archaeology - The impact upon the Public Right of Way - The impact upon the Hazardous Installation REASON FOR REFERRAL This application has been referred to the Strategic Planning Board as it is a major strategic development that includes an Environmental Impact Assessment. 1. DESCRIPTION OF SITE AND CONTEXT The application site extends to 65 hectares and is located to the south-west of the A51 at Wardle. To the south of the site is Green Lane which includes a number of industrial units and to the north- east is the North West Farmers complex. The site was once a former airfield known as RAF Calveley and consists of an area of relatively flat land which is now in agricultural use. The site is peppered with trees, hedgerows. To the east of the site is the Shropshire Union Canal which runs alongside the A51 before crossing under the road to the north of the proposed access. -

Four Decades of Hiring & Perspiring

INTERVIEW Chas Hardern Four decades of hiring & perspiring At the age of 17 Chas Hardern began a hire-boat business on the Shropshire Union and over 40 years later it is still going strong. Speaking with Chas and his wife Lindsay, Andrew Denny relates the company’s fascinating story… he very firstWaterways World of Spring 1972 carried an unassuming 1-inch high advertisement. “Farm shop & camping Tnarrow boats”, said the strapline. ABOVE: ’s first issue of 1972 included a Hardern advertisement. Waterways World “Brochure from Hardern, Starkey’s Fam, Wrenbury Heath, Nantwich, Cheshire.” In the spring of 1971, still only 17, he on later waterways restoration – were The second paragraph continued: “Milk, saw the josher Chiltern for sale at Braunston the Oxford University Canal Society and cream, butter, cheese, bacon, local and persuaded his parents to buy it for the Surrey & Hants Canal Society. honey, potatoes, canal ware, handmade £1,000, financed by the sale of a vintage Within two years it was obvious the pottery. The 12-berth narrow boats for Rolls-Royce stored in his father’s barn. business needed a better base than the hire, with skipper, are based at Henhull, The schoolboy Chas had an idea to earn family’s dairy field at Henhull, where the Nantwich, on the Shropshire Union, a living using Chiltern as a camping boat, nearby farm kitchen was used as the office. convenient also for cruising on the and during the summer the opportunity The lease of the historic Beeston Castle Macclesfield, Trent & Mersey etc.” came up to acquire the day trip boat Dorset Wharf came up for sale, and they snapped it This was the first public outing of a as well. -

12/4533N Land Next to Acton Church of England Primary School, Chester

Application No: 12/4533N Location: LAND NEXT TO ACTON CHURCH OF ENGLAND PRIMARY SCHOOL, CHESTER ROAD, ACTON, CHESHIRE, CW5 8LG Proposal: 14 houses for affordable rent, comprising four two bedroom/four person houses, nine three bedroom/five person houses and one four bedroom/six person house. The proposals also comprise the enlargement and improvement of the adjacent school car park. Applicant: Mr Philip Palmer, Mulbury Homes Ltd. Expiry Date: 21-Feb-2012 SUMMARY RECOMMENDATION Refuse MAIN ISSUES - Principle of Development - Housing Need - Sustainability of the Site - Design - Amenity - Drainage - Primary School - Highways - Ecology - Landscaping - Historic Battlefield - Renewable Energy - Other Matters REFERRAL The application is referred to the Southern Planning Committee as the application is a residential development of more than 10 dwellings which represents major development. 1. SITE DESCRIPTION The application site is part of an existing field which lies in open countryside adjacent to the main A534 Chester Road, just to the north of the hamlet of properties within the rural Parish of Acton. The site extends to approximately 0.5 hectares (1.3 acres), and is some 1.5 miles from the centre of Nantwich. The site occupies the corner of a large field and is bounded by a mature hedgerow to the west which fronts the road, and to the south by hedging which lies adjacent to the access road to Acton Church of England Primary School. Open fields lie to the north, east and over the road to the west. 2. DETAILS OF PROPOSAL The scheme seeks permission for 14 affordable dwellings and a new parking area for the school. -

Cheshire East Council Housing Supply And

CHESHIRE EAST COUNCIL HOUSING SUPPLY AND DELIVERY TOPIC PAPER August 2016 (Base date 31 March 2016) Table of Contents 1. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................. 3 2. CONTEXT – EVOLUTION OF LOCAL PLAN STRATEGY .................................. 5 3. PROPOSED CHANGES TO APPENDIX A OF THE LOCAL PLAN STRATEGY SUBMISSION VERSION ..................................................................................... 8 4. HOUSING TRAJECTORY ................................................................................. 12 5. FORECASTING – BUILD RATE AND LEAD IN METHODOLOGY ................... 25 6. SITE ALLOCATIONS ......................................................................................... 30 7. FURTHER CONSIDERATIONS POST PROPOSED CHANGES TO THE LPS PUBLIC CONSULTATION (MARCH-APRIL 2016)………………………………..32 8. NEXT STEPS & CONCLUSIONS ...................................................................... 32 9. APPENDICES.................................................................................................... 43 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 Cheshire East Council (CEC) initially produced a Housing Supply and Delivery Topic Paper (during February 2016) to support the upcoming period of Public Consultation on the Proposed Changes Version of the LPS which closed on 19 April 2016. This document had a base date of 30 September 2015 and was the most currently available data at that time. This update, with a base date of 31 March 2016 seeks to provide the full year position -

Barnett, Sales & Edleston Brook Project

Barnett, Sales & Edleston Brook Project Catchment Characterisation March 2018 This catchment characterisation provides an overview of the Barnett, Sales & Edleston brooks and summarises findings from catchment walkover surveys, desktop survey and farm advisory work delivered in catchment by Reaseheath College advisors during 2015-2017. Associated GIS layers can be requested from the RADA team by contacting [email protected] with permission from the Environment Agency. Barnett, Sales & Edleston Brook 2017 Project Overview Under the European Union (EU) WFD, the Environment Agency (EA) has a requirement to ensure that all water bodies reach ‘Good Ecological Potential / Status’ by 2027. The North West River Basin Management Plan states that 67% of water bodies in the Weaver Gowy water management catchment are not achieving good ecological status due to agricultural pollution. A large scale focus on Cheshire's agricultural practices is needed if water quality is to improve. Reaseheath College’s Farm Environmental Services were funded to work with farmers in the Barnett, Sales & Edleston Brook catchments to identify mitigation measures for water quality improvements that offer business benefits as well as environment gain. The aim of the project was to: 1. Reduce the amount of phosphate and other pollutants entering Weaver Gowy waterbodies, specifically the Barnett, Sales & Edleston Brooks, by providing targeted farm advice and suggested mitigation measures. 2. Increase biodiversity by prioritising mitigation measures that, in addition to improving water quality, create new habitat on the river corridor. 3. Increase flood attenuation opportunities by identifying areas of rural land that flood during high rainfall resulting in increased sediment loading of watercourses that could be ameliorated by natural measures such as tree breaks, sediment ponds and riparian buffer strips. -

Council Tax Charges 2020-2021

COUNCIL TAX CHARGES 2020-2021 Name A B C D E F G H Parish Total Parish Total Parish Total Parish Total Parish Total Parish Total Parish Total Parish Total Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Charge Adult Social Care 87.25 101.79 116.33 130.87 159.95 189.03 218.12 261.74 CHESHIRE EAST BOROUGH COUNCIL 915.41 1,067.97 1,220.54 1,373.11 1,678.25 1,983.38 2,288.52 2,746.22 CHESHIRE FIRE AUTHORITY 52.86 61.67 70.48 79.29 96.91 114.53 132.15 158.58 POLICE & CRIME COMMISSIONER 140.29 163.68 187.06 210.44 257.20 303.97 350.73 420.88 1,195.81 1,395.11 1,594.41 1,793.71 2,192.31 2,590.91 2,989.52 3,587.42 ACTON PARISH COUNCIL 9.75 1,205.56 11.37 1,406.48 13.00 1,607.41 14.62 1,808.33 17.87 2,210.18 21.12 2,612.03 24.37 3,013.89 29.24 3,616.66 ADLINGTON PARISH COUNCIL 16.69 1,212.50 19.47 1,414.58 22.25 1,616.66 25.03 1,818.74 30.59 2,222.90 36.15 2,627.06 41.72 3,031.24 50.06 3,637.48 AGDEN PARISH MEETING 6.95 1,202.76 8.10 1,403.21 9.26 1,603.67 10.42 1,804.13 12.74 2,205.05 15.05 2,605.96 17.37 3,006.89 20.84 3,608.26 ALDERLEY EDGE PARISH COUNCIL 45.69 1,241.50 53.30 1,448.41 60.92 1,655.33 68.53 1,862.24 83.76 2,276.07 98.99 2,689.90 114.22 3,103.74 137.06 3,724.48 ALPRAHAM PARISH COUNCIL 18.20 1,214.01 21.23 1,416.34 24.27 1,618.68 27.30 1,821.01 33.37 2,225.68 39.43 2,630.34 45.50 3,035.02 54.60 3,642.02 ALSAGER TOWN COUNCIL 56.53 1,252.34 65.95 1,461.06 75.37 1,669.78 84.79 1,878.50 103.63 2,295.94 122.47 2,713.38 141.32 3,130.84 169.58 3,757.00 ARCLID PARISH COUNCIL 11.35