Malaysia: from Hub to Exporter of Higher Education and Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (Frgs) (Amendment Year 2021)

DEPARTMENT OF HIGHER EDUCATION MINISTRY OF HIGHER EDUCATION GUIDELINES OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH GRANT SCHEME (FRGS) (AMENDMENT YEAR 2021) BAHAGIAN KECEMERLANGAN PENYELIDIKAN IPT JABATAN PENDIDIKAN TINGGI KEMENTERIAN PENGAJIAN TINGGI ARAS 7, NO. 2, MENARA 2 JALAN P5/6, PRESINT 5 62200 PUTRAJAYA TEL. NO.: 03-8870 6974/6975 FAX NO.: 03-8870 6867 TABLE OF CONTENTS Vision and Mission of Fundamental Research 3 PART 1 (INTRODUCTION) 1.1 Introduction 4 1.2 Philosophy 4 1.3 Definition 4 1.4 Purpose 4 PART 2 (APPLICATION) 2.1 General terms of application 5 2.2 Research priority areas 6 2.3 Research duration 8 2.4 Ceiling of fund 8 2.5 Research output 9 2.6 Application rules 10 PART 3 (ASSESSMENT) 3.1 Application assessment 11 3.2 Assessment criteria 12 PART 4 (MONITORING) 4.1 Research implementation 13 4.2 Monitoring 13 PART 5 (FINANCIAL REGULATIONS) 5.1 Expenditure codes 15 5.2 Use of provisions 16 PART 6 (RESULTS) 6.1 Result announcement and fund distribution 18 6.2 Agreement document and contract 18 APPENDICES 19 Application Flow Chart Monitoring Flow Chart Scheduled Monitoring Cycle List of Higher Education Institutions (Appendix A) 2 VISION AND MISSION OF FUNDAMENTAL RESEARCH Vision Competitive fundamental research for knowledge transformation and national excellence. Mission Cultivate, empower and preserve high impact research capacity to generate knowledge that can contribute to talent development, intellectual growth, new technology invention and dynamic civilization. 3 1 PART 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 INTRODUCTION The Guidelines of Fundamental Research Grant Scheme (FRGS) Amendment Year 2021 document is prepared as a reference and guide for application of research grant under the Department of Higher Education (JPT), Ministry of Higher Education (KPT). -

PTE Academic Recognition

Recognition list PTE Academic is accepted by thousands of organizations worldwide, including prestigious institutions such as Stanford University, Harvard University, and Imperial College London. PTE Academic is also accepted for visa purposes by the Australian and New Zealand government. Ability Education - Sydney Australian International College of Argentina Academies Australasia English (AICE) Academy of English Australian International High Elite Education Institute Academy of Information School Rosario Idiomas Technology Australian Pacific College Academy of Social Sciences Australian Pilot Training Alliance Australia ACN - Australian Campus Network Australian Vocational Learning Administrative Appeals Tribunal Centre Australian Capital Advance English Australis Institute of Technology Alphacrucis College and Education Territory (ACT) Apex Institute of Education Avondale College of Higher Australasian Osteopathic APM College of Business and Education Accreditation Council (AOAC) Communication Bedford College Australian National University ARC - Accountants Resource Billy Blue College of Design (ANU) Centre Blue Mountains International Hotel Australian Nursing and Midwifery Asia Pacific International College Management School (BMIHMS) Accreditation Council (ANMAC) Australasian College of Natural Campion College Australia Canberra Institute of Technology Therapies Carrick Education Canberra. Create your future - ACT Australasian College of Physical Castle College Government Scientists and Engineers in CATC Design School (Commercial -

Panduan Biasiswa Skim Staf Bagi Tahun Pengajian

PRE-UNIVERSITY APPROVED COLLEGES 1. Nexus International School Malaysia 2. Sunway College (Bandar Sunway campus) 3. Sunway College (Johor Bahru campus) 4. Kolej Tuanku Ja’afar 5. EPSOM College in Malaysia 6. Taylor’s College 7. Kolej Yayasan UEM UK APPROVED UNIVERSITIES FOR ACADEMIC YEAR 2021 FIELD OF STUDY UNIVERSITY University of Leeds London School of Economics and Political Accounting and Finance Science The University of Warwick Lancaster University The University of Warwick University of Cambridge University of Oxford Economics London School of Economics and Political Science University College London University of Leeds University of Cambridge University College London University of Oxford Law London School of Economics and Political Science King’s College London University of Leeds University of Cambridge University of Oxford The University of Warwick Durham University Mathematics / Statistics Imperial College London University College London Lancaster University University of Birmingham City, University of London London School of Economics and Political Science Actuarial Science University of Kent University of Manchester The University of Warwick University of Cambridge Imperial College London University of Oxford Computer Science/ IT/ University of Exeter Data Science University of Manchester Durham University University of Nottingham US APPROVED UNIVERSITIES FOR ACADEMIC YEAR 2021 FIELD OF STUDY UNIVERSITY University of Pennsylvania Massachusetts Institute of Technology University of California, Berkeley University of Michigan -

Global Recognition List August

Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept Africa Egypt • Global Academic Foundation - Hosting university of Hertfordshire • Misr University for Science & Technology Libya • International School Benghazi Nigeria • Stratford Academy Somalia • Admas University South Africa • University of Cape Town Uganda • College of Business & Development Studies Accept PTE Academic: pearsonpte.com/accept August 2021 Africa Technology & Technology • Abbey College Australia • Australian College of Sport & Australia • Abbott School of Business Fitness • Ability Education - Sydney • Australian College of Technology Australian Capital • Academies Australasia • Australian Department of • Academy of English Immigration and Border Protection Territory • Academy of Information • Australian Ideal College (AIC) • Australasian Osteopathic Technology • Australian Institute of Commerce Accreditation Council (AOAC) • Academy of Social Sciences and Language • Australian Capital Group (Capital • ACN - Australian Campus Network • Australian Institute of Music College) • Administrative Appeals Tribunal • Australian International College of • Australian National University • Advance English English (AICE) (ANU) • Alphacrucis College • Australian International High • Australian Nursing and Midwifery • Apex Institute of Education School Accreditation Council (ANMAC) • APM College of Business and • Australian Pacific College • Canberra Institute of Technology Communication • Australian Pilot Training Alliance • Canberra. Create your future - ACT • ARC - Accountants Resource -

Hreap V9 Complete.Pdf

HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION IN ASIA-PACIFIC VOLUME NINE Human Rights Education in Asia-Pacific—Volume Nine Published by the Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center 8F, CE Nishihonmachi Bldg., 1-7-7 Nishihonmachi, Nishi-ku, Osaka 550-0005 Japan Copyright © Asia-Pacific Human Rights Information Center, 2019 All rights reserved. The views and opinions expressed by the authors in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of hurights osaka. Printed and bound by Kinki Insatsu Pro Osaka, Japan HUMAN RIGHTS EDUCATION IN ASIA-PACIFIC VOLUME NINE Acknowledgment We acknowledge the authors who patiently worked with us in preparing the articles in this volume. We appreciate their support for the continuing work of gathering and disseminating human rights education experiences that can hopefully be useful to other people who would like to start their own human rights education program or would like to improve existing program. We also acknowledge Fidel Rillo of Mind Guerilla for the lay-out and cover design of this volume. 4 Foreword We have another important collection of articles in this volume that presents a variety of human rights education experiences in Asia. As many of us are aware, human rights institutions and defenders in the region have been facing serious challenges and obstacles to achieve human rights in many places of the world. Human rights education as well as leg- islations and policies in respective country will certainly play a crucial role to ameliorate the situation, and in this sense, we believe that this volume will provide you with insights in advancing the promotion of human rights. -

A Survey of English Language Teaching in Higher Institutions of Learning in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 1 November 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201711.0013.v1 A Survey of English Language Teaching in Higher Institutions of Learning in Kuala Lumpur Malaysia Tatiana Shulgina a* and Gopal Sagaran b* * Tatiana Shulgina, a Puchong, Selangor 47100, Malaysia * Gopal Sagaran b Puchong, Selangor 47100, Malaysia a Binary University, Malaysia; [email protected] b Binary University, Malaysia; [email protected] ABSTRACT The aim of this study is to explore the extent of English language teaching in Higher Institutions of Malaysia and investigate the current changes, trends and challenges in this niche. A sample of 100 English learners from public and private institutions participated in this study. Analysis of the responses indicated that English language is remaining to be difficult to master, due to speaking environment, proficiency of the teachers and other factors. However, the Government is on the right direction to improve this situation by following Common European Framework of Reference of Languages. As any other system, it takes time to put into realization and start up the mechanism. This observation carries a pedagogical perspective and includes the overview of the general picture based on Private, Public and Stand Alone English educational institutions. This study has highlighted the practical importance of British Framework of English learning and suggests to focus on emphasis of the learning process instead of a result. Keywords: English language; motivational intensity; survey; trends; challenges in Malaysia 1 © 2017 by the author(s). Distributed under a Creative Commons CC BY license. Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 1 November 2017 doi:10.20944/preprints201711.0013.v1 INTRODUCTION With the process of globalization, English language has become a dominant international language of 21st century. -

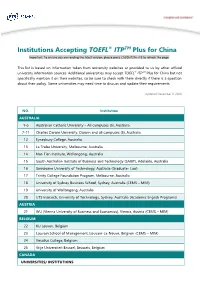

Institutions Accepting TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China Important: to Ensure You Are Reading the Latest Version, Please Press Ctrl/Shift/Fn+F5 to Refresh the Page

Institutions Accepting TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China Important: To ensure you are reading the latest version, please press Ctrl/Shift/Fn+F5 to refresh the page. This list is based on information taken from university websites or provided to us by other official university information sources. Additional universities may accept TOEFL® ITPTM Plus for China but not specifically mention it on their websites, so be sure to check with them directly if there is a question about their policy. Some universities may need time to discuss and update their requirements. Updated December 9, 2020 NO. Institution AUSTRALIA 1-6 Australian Catholic University – All campuses (6), Australia 7-11 Charles Darwin University, Darwin and all campuses (5), Australia 12 Eynesbury College, Australia 13 La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia 14 Nan Tien Institute, Wollongong, Australia 15 South Australian Institute of Business and Technology (SAIBT), Adelaide, Australia 16 Swinburne University of Technology, Australia (Graduate- Law) 17 Trinity College Foundation Program, Melbourne, Australia 18 University of Sydney Business School, Sydney, Australia (CEMS – MIM) 19 University of Wollongong, Australia 20 UTS Insearch, University of Technology, Sydney, Australia (Academic English Programs) AUSTRIA 21 WU (Vienna University of Business and Economics), Vienna, Austria (CEMS – MIM) BELGIUM 22 KU Leuven, Belgium 23 Louvain School of Management, Louvain-La-Neuve, Belgium (CEMS – MIM) 24 Vesalius College, Belgium 25 Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels, Belgium CANADA UNIVERSITIES/ -

Entrepreneurship Edition Entrepreneurship Edition

20 2017 VOL 16001 ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDITION ENTREPRENEURSHIP EDITION THE DESTINATION FOR INNOVATORS & CHANGEMAKERS cover story: ENTREPRENEURS: BORN OR MADE? Rajesh Nair Senior Lecturer and Director of the Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center pg.26 Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center pg.26 THE PLACE WHERE ENTREPRENEURS ARE MADE. pg.32 Asia School of Business (ASB) (Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia Registration: DU046(W)) 2 ASB Entrepreneurship Edition 2017 ASB Entrepreneurship Edition 2016 ASIA-READY ENTREPRENEURS CREATED HERE. Through a nurturing ecosystem built on innovation, ASB’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center is developing communities of entrepreneurs all across Asia. We will change you. You will create change. asb.edu.my 2 ASB Entrepreneurship Edition 20172016 3 ASIA-READY ENTREPRENEURS CREATED HERE. Through a nurturing ecosystem built on innovation, ASB’s Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center is developing communities of entrepreneurs all across Asia. We will change you. You will create change. asb.edu.my 4 ASB Entrepreneurship Edition 2017 ASB Entrepreneurship Edition 2016 5 A message from our President and Dean “...how our MBA 3.0 THE ASB INAUGURAL CLASS IS THERE is reshaping business 2016 Intake Total: 47 Students A PROCESS education, providing FOR CREATING immersive, real-world, ENTREPRENEURS? Action Learning projects MALAYSIA [16] n this issue we look at the making of entrepreneurs, with a feature that provide a rigorous AUSTRALIA [2] on Rajesh Nair, Director of the Nationality Innovation and Entrepreneurship Center learning platform for COTE D’IVOIRE [1] I INDIA [7] PAKISTAN [1] at Asia School of Business. 66% International BRAZIL [1] Rajesh believes that while the entrepreneurial behavior PHILIPPINES [1] 34% Malaysian entrepreneurial spirit is something some are born with, others can and should and practice.” SOUTH AFRICA [1] be made. -

Document Title

Recognition list PTE Academic is accepted by thousands of organizations worldwide, including prestigious institutions such as Stanford University, Harvard University, and Imperial College London. PTE Academic is also accepted for visa purposes by the Australian and New Zealand government. Argentina Academies Australasia Australian Institute of Music Elite Education Institute Academy of English Australian International College of Rosario Idiomas Academy of Information English (AICE) Technology Australian International High Australia Academy of Social Sciences School ACN - Australian Campus Network Australian Pacific College Australian Capital Administrative Appeals Tribunal Australian Pilot Training Alliance Advance English Australian Vocational Learning Territory (ACT) Alphacrucis College Centre Australasian Osteopathic Apex Institute of Education Australis Institute of Technology Accreditation Council (AOAC) APM College of Business and and Education Australian National University Communication Avondale College of Higher (ANU) ARC - Accountants Resource Education Australian Nursing and Midwifery Centre Bedford College Accreditation Council (ANMAC) Asia Pacific International College Billy Blue College of Design Canberra Institute of Technology Australasian College of Natural Blue Mountains International Hotel Canberra. Create your future - ACT Therapies Management School (BMIHMS) Government Australasian College of Physical Campion College Australia Endeavour Scholarships and Scientists and Engineers in Carrick Education Fellowships Medicine -

Charging the Asean Ecosystem

20 16 VOL 002 CORPORATE EDITION CORPORATE THE DESTINATION FOR INNOVATORS & CHANGEMAKERS cover story: TURBO- CHARGING THE ASEAN ECOSYSTEM ASB CASE STUDY: TESLA Zalina Jamaluddin Director of Corporate Development NAIL IT, SCALE IT, SAIL IT pg.25 pg.29 FROM ZERO TO GROUNDBREAKING IN 12 MONTHS pg.07 Asia School of Business (ASB) (Ministry of Higher Education, Malaysia Registration: DU046(W)) BECOME AN AGENT OF CHANGE. #iamAsia LET’S CREATE A LEGACY. ASB will merge the power of Asian ambition with MIT Sloan’s academic rigor. This newest MIT Sloan collaboration, in partnership with Bank Negara Malaysia, the Central Bank of Malaysia, is about connecting two institutions that are grounded in excellence. Legacy is guided by a simple principle: leave the world better than you found it. As a founding member of ASB, a broad range of endowments and sponsorships can drive corporate or personal contribution and recognition. Scholarships are another way to perpetuate your status as a founding supporter. A future entrepreneur, could have sat in a lecture hall, studied in a library, workshopped in a room, or have been mentored by a professor, whose chair carries your name. These are powerful ways to create your legacy and become a privileged member and friend of ASB. You would also gain: • Access to world-class faculty & research • Access to talented ASB students and MIT Sloan students • Build a network of Asia industry and MIT academic experts • Become ASB’s family of first-class corporate partners For more information, email Zalina Jamaluddin, Director of Corporate Development at [email protected] Our mission for A message from our President and Dean ASIA SCHOOL OF BUSINESS Asia School of Business Asia School of Business began its journey a year ago, with the BOARD OF GOVERNORS is to turbo charge the goal of bringing MIT Sloan's quality of learning and innovation to Asia. -

Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #Myduitstory Short Video

#MyDuitStory Short Video Competition - Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #MyDuitStory Short Video Competition (Competition) is a financial education initiative by Financial Education Network (FEN) led by Bank Negara Malaysia (the Organiser) in collaboration with the Ministry of Higher Education. The Competition aims to raise awareness on the importance of personal financial management among youth. 2. Eligibility The Competition is open to all Malaysian undergraduate students (Students) of participating universities (please refer to item 13 below). 3. Registration a) Students may submit an individual entry OR as a team of not more than 4 members (including Team Leader but excluding talents). b) Students are required to register at https://myduitstory.my/ by providing the following details: i. Name (Individual/Team Leader), e-mail address, contact number, and university name of the Individual/Team Leader the Students represent. ii. Upon registration, the Individual/Team Leader will receive a confirmation e-mail which include: ✓ a link to a Google Form for the Individual/Team Leader to fill in the details of the Lecturer(s) and the Team, if applicable. ✓ Facebook link to the Virtual Briefing by FINAS and AKPK. c) Team Members can be from the same or different participating university. d) Only participating universities for the Competition are eligible for the 'University With Most Entries Submitted’ prize category. e) The Lecturer is to validate the status of the Students. f) Students may submit multiple entries with different Coverage. 4. Important Dates a) Registration: 28 December 2020 – 31 January 2021 b) Virtual Briefing via Facebook Live: 13 January 2021 i. FINAS - on creating an engaging video and cultural nuances ii. -

Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #Myduitstory Short Video

#MyDuitStory Short Video Competition - Terms and Conditions 1. Introduction #MyDuitStory Short Video Competition (Competition) is a financial education initiative by Financial Education Network (FEN) led by Bank Negara Malaysia (the Organiser) in collaboration with the Ministry of Higher Education. The Competition aims to raise awareness on the importance of personal financial management among youth. 2. Eligibility The Competition is open to all Malaysian undergraduate students (Students) of participating universities (please refer to item 13 below). 3. Registration a) Students may submit an individual entry OR as a team of not more than 4 members (including Team Leader but excluding talents). b) Students are required to register at https://myduitstory.my/ by providing the following details: i. Name (Individual/Team Leader), e-mail address, contact number, and name of the university represented by the Individual/Team Leader. ii. Upon registration, the Individual/Team Leader will receive a confirmation e-mail which include: ✓ a link to a Google Form for the Individual/Team Leader to fill in the details of the Lecturer(s) and the Team, if applicable. ✓ Facebook link to the Virtual Briefing by FINAS and AKPK. c) Team Members can be from the same or different participating universities. d) Only registered university in the Google Form is eligible for the 'University With Most Entries Submitted’ prize category. e) The Lecturer is to validate the status of the Students. f) Students may submit multiple entries with different Coverage. 4. Important Dates a) Registration: 28 December 2020 – 31 January 2021 b) Virtual Briefing via Facebook Live: 13 January 2021 i. FINAS - on creating an engaging video and cultural nuances ii.