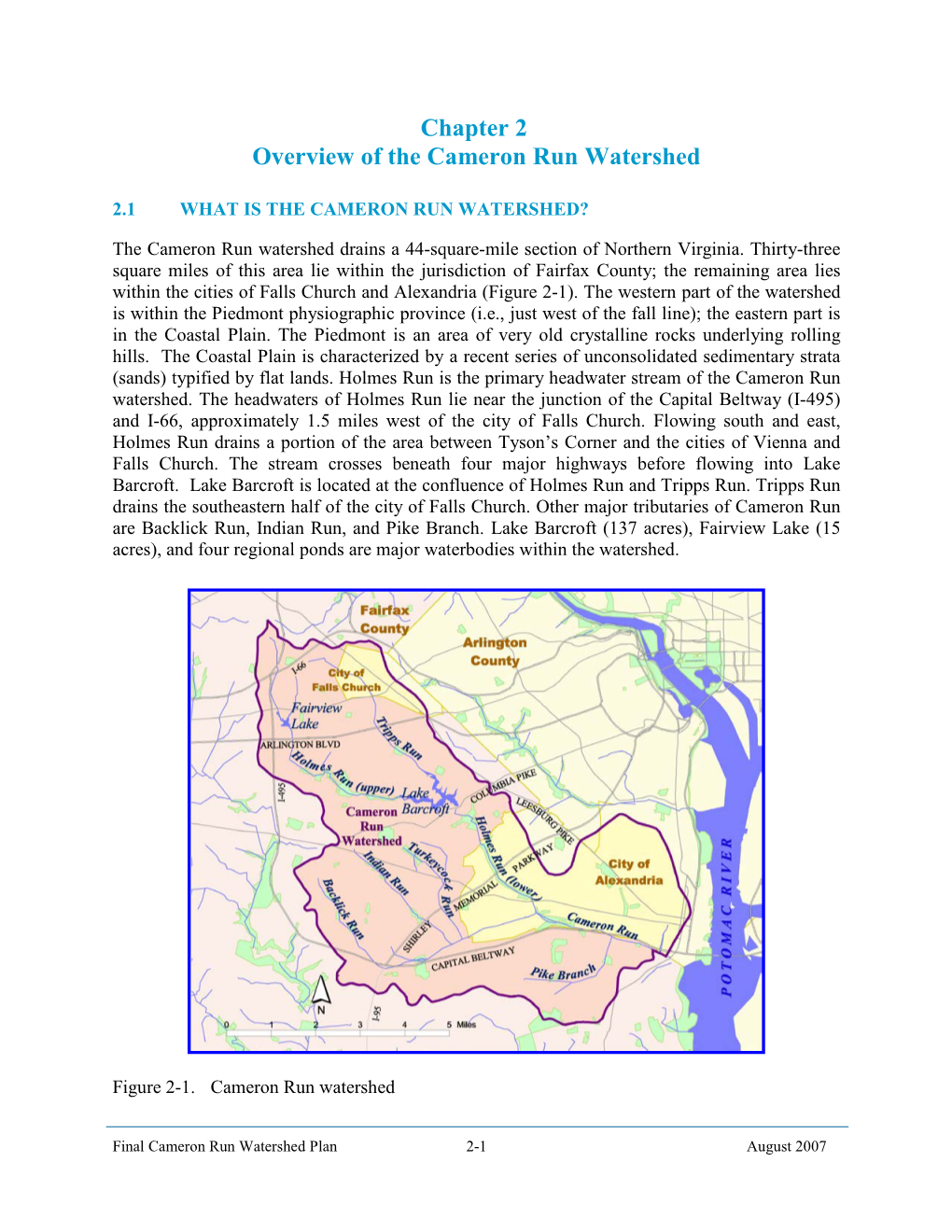

Overview of the Cameron Run Watershed

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Photo by King Montgomery. by Photo Table of Contents 7 Foreword 8 Fly Fishing Virginia 11 Flies to Use in Virginia 17 Top Virginia Fly Fishing Waters 19 Accotink Creek 21 Back Creek 25 Big Wilson Creek 29 Briery Creek Lake 33 Chesapeake Bay Islands Beasley. Beau by Photo 37 Conway River 41 Dragon Run 43 Gwynn Island 47 Holmes Run Beasley. Beau by Photo 51 Holston River, South Fork 53 Jackson River, Lower Section 59 Jackson River, Upper Section 63 James River, Lower Section 67 James River, Upper Section 71 Lake Brittle 75 Lynnhaven River, Bay, & Inlet 79 Maury River 4 Photo by Eric Evans. Eric by Photo 83 Mossy Creek 87 New River, Lower Section 91 New River, Upper Section 95 North Creek 97 Passage Creek 99 Piankatank River 101 Rapidan River, Lower Section Beasley. Beau by Photo 105 Rapidan River, Upper Section 109 Rappahannock River, Lower Section 113 Rappahannock River, Upper Section 117 Rivanna River 121 Rose River 125 Rudee Inlet 129 Shenandoah River, North Fork Photo by Beau Beasley. Beau by Photo 133 Shenandoah River, South Fork 137 South River 141 St. Mary’s River 145 Whitetop Laurel Creek Chris Newsome. by Photo 148 Private Waters 151 Resources 155 Conservation 156 Other No Nonsense Guides 158 Fly Fishing Knots 5 Arlington 81 66 Interstate South U.S. Highway River 95 State Highway 81 Other Roadway 64 64 Richmond Virginia Boat Launch 64 460 Fish Hatchery Roanoke Hampton 81 95 To Campground 77 58 Hermitage 254 To Grottoes To 340 Staunton ay rkw n Pa ema Hop 254 ver Ri 250 h ut So 340 340 1 Waynesboro To 2 Staunton 2 3 664 64 624 To Charlottesville 250 er iv R h ut 64 So 624 To 1 Constitution Park–Home of Charlottesville Virginia Fly Fishing Festival 2 Good Wading 3 Low water dam South River 136 South River outh River is one of the most underrated fisheries in the Old Dominion. -

Native Vascular Flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia

Native Vascular Flora City of Alexandria, Virginia Photo by Gary P. Fleming December 2015 Native Vascular Flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia December 2015 By Roderick H. Simmons City of Alexandria Department of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities, Natural Resources Division 2900-A Business Center Drive Alexandria, Virginia 22314 [email protected] Suggested citation: Simmons, R.H. 2015. Native vascular flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia. City of Alexandria Department of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities, Alexandria, Virginia. 104 pp. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Climate ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Geology and Soils .................................................................................................................... 3 History of Botanical Studies in Alexandria .............................................................................. 5 Methods ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Results and Discussion .................................................................................................................... -

Authorization to Discharge Under the Virginia Stormwater Management Program and the Virginia Stormwater Management Act

COMMONWEALTHof VIRGINIA DEPARTMENTOFENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Permit No.: VA0088587 Effective Date: April 1, 2015 Expiration Date: March 31, 2020 AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE VIRGINIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PROGRAM AND THE VIRGINIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT ACT Pursuant to the Clean Water Act as amended and the Virginia Stormwater Management Act and regulations adopted pursuant thereto, the following owner is authorized to discharge in accordance with the effluent limitations, monitoring requirements, and other conditions set forth in this state permit. Permittee: Fairfax County Facility Name: Fairfax County Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System County Location: Fairfax County is 413.15 square miles in area and is bordered by the Potomac River to the East, the city of Alexandria and the county of Arlington to the North, the county of Loudoun to the West, and the county of Prince William to the South. The owner is authorized to discharge from municipal-owned storm sewer outfalls to the surface waters in the following watersheds: Watersheds: Stormwater from Fairfax County discharges into twenty-two 6lh order hydrologic units: Horsepen Run (PL18), Sugarland Run (PL21), Difficult Run (PL22), Potomac River- Nichols Run-Scott Run (PL23), Potomac River-Pimmit Run (PL24), Potomac River- Fourmile Run (PL25), Cameron Run (PL26), Dogue Creek (PL27), Potomac River-Little Hunting Creek (PL28), Pohick Creek (PL29), Accotink Creek (PL30),(Upper Bull Run (PL42), Middle Bull Run (PL44), Cub Run (PL45), Lower Bull Run (PL46), Occoquan River/Occoquan Reservoir (PL47), Occoquan River-Belmont Bay (PL48), Potomac River- Occoquan Bay (PL50) There are 15 major streams: Accotink Creek, Bull Run, Cameron Run (Hunting Creek), Cub Run, Difficult Run, Dogue Creek, Four Mile Run, Horsepen Run, Little Hunting Creek, Little Rocky Run, Occoquan Receiving Streams: River, Pimmit run, Pohick creek, Popes Head Creek, Sugarland Run, and various other minor streams. -

A Direct Route to George Washington's Home

Office of Historic Alexandria City of Alexandria, Virginia Out of the Attic A direct route to George Washington’s home Alexandria Times, February 12, 2015 Image: Great Hunting Creek. Photo, Office of Historic Alexandria. his week, we continue our discussion of the man-made changes to Great Hunting Creek T and Cameron Run. With the construction of the Richmond Highway causeway across the creek in 1809 and then the building of a streetcar rail bridge across the wide mouth of the waterway at the turn of the 20th century, impediments to proper drainage were well in place by 1900. But within 30 years, a major new construction project would replace the elevated rail bridge with a permanent land form, further restricting the ebb and flow of natural currents and drainage flow far upstream. At the time the streetcar rail bridge was under construction, an Alexandria business group first proposed a new roadway to link the nation’s capital with the tourist haven, Mount Vernon, 15 miles away. As projected, the new highway would cross the Potomac River near Arlington House, as well as at Great Hunting Creek on suspension bridges high above the waterways, named the “Memorial Bridges” in honor of the Civil War dead and to reflect the reunification of the Union and Confederate states. In the rural wilderness of Fairfax County, south of Alexandria, the highway would include 13 rest areas, each featuring a large pavilion reflecting one of the original colonies, with landscaping, architecture and exhibits appropriate to the earliest states. By the late 1920s, Congress finally authorized construction of the George Washington Memorial Parkway, in honor of the upcoming 200th birthday of the nation’s first president in 1932 as promoted by Alexandria businessmen, albeit without the more lavish plans espoused nearly three decades earlier. -

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy

Brook Trout Outcome Management Strategy Introduction Brook Trout symbolize healthy waters because they rely on clean, cold stream habitat and are sensitive to rising stream temperatures, thereby serving as an aquatic version of a “canary in a coal mine”. Brook Trout are also highly prized by recreational anglers and have been designated as the state fish in many eastern states. They are an essential part of the headwater stream ecosystem, an important part of the upper watershed’s natural heritage and a valuable recreational resource. Land trusts in West Virginia, New York and Virginia have found that the possibility of restoring Brook Trout to local streams can act as a motivator for private landowners to take conservation actions, whether it is installing a fence that will exclude livestock from a waterway or putting their land under a conservation easement. The decline of Brook Trout serves as a warning about the health of local waterways and the lands draining to them. More than a century of declining Brook Trout populations has led to lost economic revenue and recreational fishing opportunities in the Bay’s headwaters. Chesapeake Bay Management Strategy: Brook Trout March 16, 2015 - DRAFT I. Goal, Outcome and Baseline This management strategy identifies approaches for achieving the following goal and outcome: Vital Habitats Goal: Restore, enhance and protect a network of land and water habitats to support fish and wildlife, and to afford other public benefits, including water quality, recreational uses and scenic value across the watershed. Brook Trout Outcome: Restore and sustain naturally reproducing Brook Trout populations in Chesapeake Bay headwater streams, with an eight percent increase in occupied habitat by 2025. -

Natural Resources Technical Report

TRANSFORM 66 OUTSIDE the Beltway I-66 CORRIDOR 66 IMPROVEMENTS PROJECT Multimodal Solutions - 495 to Haymarket Tier 2 Draft Environmental Assessment 193 Town of Natural Resources TechnicalTown of Report Middleburg Herndon LOUDOUN FAUQUIER 50 267 Washington Dulles McLean International Airport 309 28 286 Tysons Corner West Falls Church 7 Chantilly Dunn Loring FALLS 123 CHURCH 29 Vienna LOUDOUN Fair Lakes 50 FAIRFAX CO. 66 15 FAIRFAX CITY Centreville 286 29 236 Manassas National Battlefield Park Haymarket Fairfax Station Springfield 66 Gainesville 234 28 MANASSAS PARK PRINCE WILLIAM 29 FAUQUIER 234 123 286 215 Ft. Belvoir MANASSAS MAY 12, 2015 Tier 2 Draft Environmental Assessment Natural Resources Technical Report Draft – May 12, 2015 I-66 Corridor Improvements Project – Natural Resources Technical Report May 12, 2015 Table of Contents Chapter 1 – Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1 Project Description ..................................................................................................................... 1-1 1.2 Methods ...................................................................................................................................... 1-2 Chapter 2 – Affected Environment ......................................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 Water Resources ...................................................................................................................... -

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 OMB No. 1024-0018 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NOV 0 ·~ 2013 National Register of Historic Places NAT. Re018TiR OF HISTORIC PlACES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instructions in National Register Bulletin, How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form. If any item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classification, materials, and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional certification comments, entries, and narrative items on continuation sheets if needed (NPS Form 10-900a). 1. Name of Property historic name George Washington Birthplace National Monument other names/site number Wakefield. Popes Creek Plantation , VDHR File #096-0026 2. Location 1732 Popes Creek Road not for publication street & number L-----' city or town Colonial Beach ~ vicinity state Vir inia code VA county Westmoreland code _ _;_:19'--=-3- zip code -"'2=2:....;.4"""43.;;...._ ___ 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this _!__nomination_ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property .K._ meets __ does not meet the National Register Criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant at the following level(s) of significance: x_ b state ' Ide "x n J.VIA.rVI In my opinion, the property .x..._ meets_ does not meet the National Register criteria. -

2019 Trout Program Maps

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 FOUR DOLLARS Inside: 2019 Trout Program Maps SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2018 Contents 5 How Sweet Sweet Sweet It Is! By Mike Roberts With support from the Ward Burton Wildlife Foundation, volunteers, and business partners, a citizen science project aims to help a magnificent songbird in the Roanoke River basin. 10 Hunting: A Foundation For Life By Curtis J. Badger A childhood spent afield gives the author reason to reflect upon a simpler time, one that deeply shaped his values. 14 Women Afield: Finally By John Shtogren There are many reasons to cheer the trend of women’s interest in hunting and fishing, and the outdoors industry takes note. 20 What’s Up With Cobia? By Ken Perrotte Virginia is taking a lead in sound management of this gamefish through multi-state coordination, tagging efforts, and citation data. 24 For The Love Of Snakes By David Hart Snakes are given a bad rap, but a little knowledge and the right support group can help you overcome your fears. 28 The Evolution Of Cute By Jason Davis Nature has endowed young wildlife with a number of strategies for survival, cuteness being one of them. 32 2019 Trout Program Maps By Jay Kapalczynski Fisheries biologists share the latest trout stocking locations. 38 AFIELD AND AFLOAT 41 A Walk in the Woods • 42 Off the Leash 43 Photo Tips • 45 On the Water • 46 Dining In Cover: A female prothonotary warbler brings caterpillars to her young. See page 5. ©Mike Roberts Left: A handsome white-tailed buck pauses while feeding along a fence line. -

WRRC Vwc 201002.Pdf (2.131Mb)

Virginia Water Resources Research Center Blacksburg, Virginia February 2010 (No. 52) Animal tracks beside a small stream in Montgomery County, Va., February 7, 2010. For a review of 2009 in water photos, see the Water Status Report section. IN THIS ISSUE Editor’s Comment: Virginia Water Radio 2 At the Water Center 32 Teaching Water 2 USGS/NIWR Competitive Grants Program 32 Virginia’s Infrastructure Gets Graded by the For the Record: Groundwater 33 American Society of Civil Engineers 3 Groundwater Photo Essay; Limestone Lagoons Water Status Report 8 in the Dominican Republic 36 In and Out of the News 14 Index to Previous Water Centrals 37 Va. Govt. Water Issues Overview 22 You Get the Last Word 40 Notices 26 2 Editor’s Comment Introducing Virginia Water Radio By Alan Raflo, Virginia Water Central Editor Here’s a history question. What common everyday item owes it origin—in part at least—to the following men, all active from the mid-1800s to the early 1900s: James Maxwell, Heinrich Hertz, Nikola Tesla, Alexander Popov, and Guglielmo Marconi? All of these men, along with other scientists and engineers, contributed to the invention or development of the radio. From Robert Peary’s 1909 message upon reaching the North Pole, to the World War II messages from Franklin Roosevelt and Winston Churchill, to the daily talk shows that enliven and influence politics and culture in 2010, radio has been an indispensible part of modern communications. The Virginia Water Resources Research Center is trying to use this old, reliable technology—matched with some 21st Century enhancements—to give Virginia citizens another way to stay informed about our state’s water resources. -

The Northern Part of Richmond Highway Is Located in the Belle Haven and Little Hunting Creek Watersheds, While the Southern Segm

1 NOMINATION. Richmond Highway Corridor ATTACHMENT A. Revise and strengthen land use and transportation recommendations of the Plan for Richmond Highway Corridor to reduce stormwater runoff, be consistent with county watershed plans, and support the Policy Plan’s environmental objective 2, policy k. 1. Revise and update the description of the Richmond Highway Corridor Area to reflect current knowledge about environmental impacts, esp. on water quality. To the following existing paragraph (p. 25), The northern part of Richmond Highway is located in the Belle Haven and Little Hunting Creek watersheds, while the southern segment is in the Dogue Creek watershed and is affected by the floodplains and stream valleys of Dogue Creek. The entire corridor is located in the Coastal Plain geologic province and thus lies in a zone of extensive slippage-prone swelling clays and sensitive aquifer recharge. add Development in the Richmond Corridor has degraded all three of these watersheds by increasing stormwater runoff from impervious surfaces and decreasing aquifer recharge. 2. Add a land use recommendation to p. 27: Offer incentives for development and redevelopment projects to reduce imperviousness and achieve better control over stormwater runoff in the Richmond Highway Corridor. Possible incentives to be created were recommended by the Little Hunting Creek Watershed Plan and are described in Attachment B. It is recommended that an overlay district, as suggested by the watershed plan, be created to implement these changes in the Richmond Highway Corridor as soon as possible, without waiting for county-wide changes in policy. The urgency is due to the inadequacy of stormwater controls in the Richmond Highway Corridor and consequent damage to three watersheds, the Potomac River, and the Chesapeake Bay. -

Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment: Potomac River Sustainable Flow and Water Resources Analysis

Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment: Potomac River Sustainable Flow and Water Resources Analysis April 2014 Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment: Potomac River Sustainable Flow and Water Resources Analysis United States Army Corps of Engineers, Baltimore District The Natural Conservancy Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin Final Report April 2014 Recommended citation: U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, The Nature Conservancy, and Interstate Commission on the Potomac River Basin. 2014. Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment: Potomac River Sustainable Flow and Water Resources Analysis. Final Report. 107 pp. and 11 appendices. Cover photograph: Great Falls on the Potomac River as seen from Virginia. Jim Palmer (ICPRB) Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment Abstract The Middle Potomac River Watershed Assessment (MPRWA) was a collaborative effort to assess the relationship between streamflow alteration and ecological response in the Potomac River and its tributaries in a study area defined as the Middle Potomac. The assessment is comprised of five distinct components: (1) a large river environmental flow needs assessment, (2) a stream and small rivers environmental flow needs assessment, (3) a projection of future water uses, (4) a stakeholder engagement process, and (5) development of a concept or scope for a strategic comprehensive plan for watershed management. This information can be used to balance and mitigate water use conflicts and prevent ecological degradation. To assess flow needs in the Potomac watershed, the Ecologically Sustainable Water Management (ESWM) approach was used for large rivers and the Ecological Limits of Hydrologic Alteration (ELOHA) framework was adapted for streams and small rivers. In the large rivers included in this study, based on currently available information, there has been no discernible adverse ecological impact on focal species due to human modification of flows. -

TMDL) Action Plan

City of Alexandria, Virginia Bacteria Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) Action Plan For compliance with 9VAC25-890, “General VPDES Permit for Discharges of Stormwater from Small Municipal Separate Storm Sewer Systems, Permit No. VAR040057 June 17, 2015 Revised November 20, 2015 Revised June 30, 2016 Prepared by: City of Alexandria, Virginia Department of Transportation and Environmental Services Stormwater Management Division PAGE LEFT INTENTIONALLY BLANK Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Background ......................................................................................................................... 1 3. Legal Authorities to Reduce Pollutant of Concern ............................................................... 3 4. Planning Framework ........................................................................................................... 3 a. Principles ......................................................................................................................... 3 b. Action Goals .................................................................................................................... 4 5. TMDL Development and Load Determination ..................................................................... 4 a. Four Mile Run Non-Tidal ................................................................................................. 4 b. Four Mile Run Tidal ........................................................................................................