Natural Resources Technical Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Table of Contents

Photo by King Montgomery. by Photo Table of Contents 7 Foreword 8 Fly Fishing Virginia 11 Flies to Use in Virginia 17 Top Virginia Fly Fishing Waters 19 Accotink Creek 21 Back Creek 25 Big Wilson Creek 29 Briery Creek Lake 33 Chesapeake Bay Islands Beasley. Beau by Photo 37 Conway River 41 Dragon Run 43 Gwynn Island 47 Holmes Run Beasley. Beau by Photo 51 Holston River, South Fork 53 Jackson River, Lower Section 59 Jackson River, Upper Section 63 James River, Lower Section 67 James River, Upper Section 71 Lake Brittle 75 Lynnhaven River, Bay, & Inlet 79 Maury River 4 Photo by Eric Evans. Eric by Photo 83 Mossy Creek 87 New River, Lower Section 91 New River, Upper Section 95 North Creek 97 Passage Creek 99 Piankatank River 101 Rapidan River, Lower Section Beasley. Beau by Photo 105 Rapidan River, Upper Section 109 Rappahannock River, Lower Section 113 Rappahannock River, Upper Section 117 Rivanna River 121 Rose River 125 Rudee Inlet 129 Shenandoah River, North Fork Photo by Beau Beasley. Beau by Photo 133 Shenandoah River, South Fork 137 South River 141 St. Mary’s River 145 Whitetop Laurel Creek Chris Newsome. by Photo 148 Private Waters 151 Resources 155 Conservation 156 Other No Nonsense Guides 158 Fly Fishing Knots 5 Arlington 81 66 Interstate South U.S. Highway River 95 State Highway 81 Other Roadway 64 64 Richmond Virginia Boat Launch 64 460 Fish Hatchery Roanoke Hampton 81 95 To Campground 77 58 Hermitage 254 To Grottoes To 340 Staunton ay rkw n Pa ema Hop 254 ver Ri 250 h ut So 340 340 1 Waynesboro To 2 Staunton 2 3 664 64 624 To Charlottesville 250 er iv R h ut 64 So 624 To 1 Constitution Park–Home of Charlottesville Virginia Fly Fishing Festival 2 Good Wading 3 Low water dam South River 136 South River outh River is one of the most underrated fisheries in the Old Dominion. -

Shoreline Situation Report Counties of Fairfax and Arlington, City of Alexandria

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 1979 Shoreline Situation Report Counties of Fairfax and Arlington, City of Alexandria Dennis W. Owen Virginia Institute of Marine Science Lynne C. Morgan Virginia Institute of Marine Science Nancy M. Sturm Virginia Institute of Marine Science Robert J. Byrne Virginia Institute of Marine Science Carl H. Hobbs III Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Environmental Indicators and Impact Assessment Commons, Natural Resources Management and Policy Commons, and the Water Resource Management Commons Recommended Citation Owen, D. W., Morgan, L. C., Sturm, N. M., Byrne, R. J., & Hobbs, C. H. (1979) Shoreline Situation Report Counties of Fairfax and Arlington, City of Alexandria. Special Report tn Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering No. 166. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, William & Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/ V5K134 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Shoreline Situation Report COUNTIES OF FAIRFAX AND ARLINGTON, CITY OF ALEXANDRIA Prepared and Published With Funds Provided to the Commonwealth by the Office of Coastal Zone Management, National Oceanic and Atmospheric·Administration, Grant Nos. 04-7-158-44041 and 04-8-M01-309 Special Report In Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Number 166 of the VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 1979 Shoreline Situation Report COUNTIES OF FAIRFAX AND ARLINGTON, CITY OF AL.EXANDRIA Prepared by: Dennis W. -

Native Vascular Flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia

Native Vascular Flora City of Alexandria, Virginia Photo by Gary P. Fleming December 2015 Native Vascular Flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia December 2015 By Roderick H. Simmons City of Alexandria Department of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities, Natural Resources Division 2900-A Business Center Drive Alexandria, Virginia 22314 [email protected] Suggested citation: Simmons, R.H. 2015. Native vascular flora of the City of Alexandria, Virginia. City of Alexandria Department of Recreation, Parks, and Cultural Activities, Alexandria, Virginia. 104 pp. Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................ 2 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 2 Climate ..................................................................................................................................... 2 Geology and Soils .................................................................................................................... 3 History of Botanical Studies in Alexandria .............................................................................. 5 Methods ............................................................................................................................................ 7 Results and Discussion .................................................................................................................... -

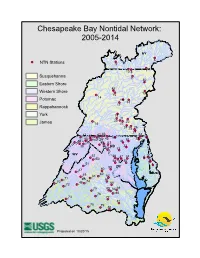

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014

Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: 2005-2014 NY 6 NTN Stations 9 7 10 8 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 Western Shore 12 15 14 Potomac 16 13 17 Rappahannock York 19 21 20 23 James 18 22 24 25 26 27 41 43 84 37 86 5 55 29 85 40 42 45 30 28 36 39 44 53 31 38 46 MD 32 54 33 WV 52 56 87 34 4 3 50 2 58 57 35 51 1 59 DC 47 60 62 DE 49 61 63 71 VA 67 70 48 74 68 72 75 65 64 69 76 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Chesapeake Bay Nontidal Network: All Stations NTN Stations 91 NY 6 NTN New Stations 9 10 8 7 Susquehanna 11 82 Eastern Shore 83 12 Western Shore 92 15 16 Potomac 14 PA 13 Rappahannock 17 93 19 95 96 York 94 23 20 97 James 18 98 100 21 27 22 26 101 107 24 25 102 108 84 86 42 43 45 55 99 85 30 103 28 5 37 109 57 31 39 40 111 29 90 36 53 38 41 105 32 44 54 104 MD 106 WV 110 52 112 56 33 87 3 50 46 115 89 34 DC 4 51 2 59 58 114 47 60 35 1 DE 49 61 62 63 88 71 74 48 67 68 70 72 117 75 VA 64 69 116 76 65 66 73 77 81 78 79 80 Prepared on 10/20/15 Table 1. -

Authorization to Discharge Under the Virginia Stormwater Management Program and the Virginia Stormwater Management Act

COMMONWEALTHof VIRGINIA DEPARTMENTOFENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY Permit No.: VA0088587 Effective Date: April 1, 2015 Expiration Date: March 31, 2020 AUTHORIZATION TO DISCHARGE UNDER THE VIRGINIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT PROGRAM AND THE VIRGINIA STORMWATER MANAGEMENT ACT Pursuant to the Clean Water Act as amended and the Virginia Stormwater Management Act and regulations adopted pursuant thereto, the following owner is authorized to discharge in accordance with the effluent limitations, monitoring requirements, and other conditions set forth in this state permit. Permittee: Fairfax County Facility Name: Fairfax County Municipal Separate Storm Sewer System County Location: Fairfax County is 413.15 square miles in area and is bordered by the Potomac River to the East, the city of Alexandria and the county of Arlington to the North, the county of Loudoun to the West, and the county of Prince William to the South. The owner is authorized to discharge from municipal-owned storm sewer outfalls to the surface waters in the following watersheds: Watersheds: Stormwater from Fairfax County discharges into twenty-two 6lh order hydrologic units: Horsepen Run (PL18), Sugarland Run (PL21), Difficult Run (PL22), Potomac River- Nichols Run-Scott Run (PL23), Potomac River-Pimmit Run (PL24), Potomac River- Fourmile Run (PL25), Cameron Run (PL26), Dogue Creek (PL27), Potomac River-Little Hunting Creek (PL28), Pohick Creek (PL29), Accotink Creek (PL30),(Upper Bull Run (PL42), Middle Bull Run (PL44), Cub Run (PL45), Lower Bull Run (PL46), Occoquan River/Occoquan Reservoir (PL47), Occoquan River-Belmont Bay (PL48), Potomac River- Occoquan Bay (PL50) There are 15 major streams: Accotink Creek, Bull Run, Cameron Run (Hunting Creek), Cub Run, Difficult Run, Dogue Creek, Four Mile Run, Horsepen Run, Little Hunting Creek, Little Rocky Run, Occoquan Receiving Streams: River, Pimmit run, Pohick creek, Popes Head Creek, Sugarland Run, and various other minor streams. -

Potomac River Water Quality and Habitat Assessment Overall Condition 2012-2014

Larry Hogan, Governor Boyd Rutherford, Lt. Governor Mark Belton, Secretary Tidewater Ecosystem Assessment Joanne Throwe, Deputy Secretary Potomac River Water Quality and Habitat Assessment Overall Condition 2012-2014 The Potomac River watershed includes area in Maryland, Virginia, Pennsylvania, West Virginia and Washington D.C. For the purpose of this report, the basin is divided into four regions: the Upper Potomac, Shenandoah, Middle Potomac and Lower Potomac (Figure 1). Land use in the upper Potomac River watershed was estimated to be 69% forest and 22% agriculture (Figure 1, Table 1).1 The Upper Potomac watershed is largely within West Virginia (54%), with other portions in Pennsylvania (22%), Maryland (18%) and Virginia (7%). Impervious surfaces cover 1% of the Maryland potion of the Upper river basin (Table 1).2 Land use in the Shenandoah watershed was estimated to be 56% forest and 34% agriculture. The Shenandoah watershed is almost entirely in Virginia (96%), with a small area in West Virginia (4%). Land use in the Middle Potomac watershed was estimated to be 44% agriculture, 32% forest and 20% developed. The Middle Potomac watershed includes areas in Maryland (55%), Virginia (34%), Pennsylvania (13%) and Washington D.C. (0.1%). Impervious surfaces cover 7% of the Maryland potion of the Middle river basin. Land use in the Lower Potomac watershed was estimated to be 41% forest, 30% developed, and 16% agriculture. The Lower Potomac watershed includes Figure 1 Potomac River basin Top panel shows state boundaries and the individual watersheds. Bottom panel shows the land use throughout the basin for 2011.1 Potomac River Water Quality and Habitat Assessment Overall Condition 2012-2014 1 areas in Virginia (56%), Maryland (42%) and Washington D.C. -

Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You!

American Council of Engineering Companies of Metropolitan Washington Water & Wastewater Business Opportunities Networking Luncheon Presented by Matthew Doyle, Branch Chief, Wastewater Design and Construction Division Department of Public Works and Environmental Services Working for You! A Fairfax County, VA, publication August 20, 2019 Introduction • Matt Doyle, PE, CCM • Working as a Civil Engineer at Fairfax County, DPWES • BSCE West Virginia University • MSCE Johns Hopkins University • 25 years in the industry (Mid‐Atlantic Only) • Adjunct Hydraulics Professor at GMU • Director GMU‐EFID (Student Organization) Presentation Objectives • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization (Staff) • Snapshot of our Current Projects • New Opportunities To work with DPWES • Use of Technologies and Trends • Helpful Hyperlinks Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Infrastructure • Wastewater Collection System • 3,400 Miles of Sanitary Sewer (Average Age 60 years old) • 61 Pumping Stations (flow ranges are from 25 GPM to 25 MGD) • 90 Flow Meters (Mostly billing meters) • 135 Grinder pumps • Wastewater Treatment Plant • 1 Wastewater Treatment Plant • Noman M. Cole Pollution Control Plant, Lorton • 67 MGD • Laboratory • Reclaimed Water Reuse System • 6.6 MGD • 2 Pump Stations • 0.750 MG Storage Tank • Level 1 Compliance • Convanta, Golf Course and Ball Fields Overview of Fairfax County Wastewater Organization • Wastewater Management Program (Three Areas) – Planning & Monitoring: • Financial, -

Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2011/488 ON THE COVER Potomac River near Paw Paw, West Virginia Photograph by: Tom Paradis, NPS. Annual and Seasonal Trends in Discharge of National Capital Region Streams Natural Resource Technical Report NPS/NCRN/NRTR—2011/488 John Paul Schmit National Park Service Center for Urban Ecology 4598 MacArthur Blvd. NW Washington, DC 20007 September, 2011 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Stewardship and Science Fort Collins, Colorado The National Park Service, Natural Resource Stewardship and Science office in Fort Collins, Colorado publishes a range of reports that address natural resource topics of interest and applicability to a broad audience in the National Park Service and others in natural resource management, including scientists, conservation and environmental constituencies, and the public. The Natural Resource Technical Report Series is used to disseminate results of scientific studies in the physical, biological, and social sciences for both the advancement of science and the achievement of the National Park Service mission. The series provides contributors with a forum for displaying comprehensive data that are often deleted from journals because of page limitations. All manuscripts in the series receive the appropriate level of peer review to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and designed and published in a professional manner. This report received formal peer review by subject-matter experts who were not directly involved in the collection, analysis, or reporting of the data, and whose background and expertise put them on par technically and scientifically with the authors of the information. -

Summary of Water Resource and Related Data in Loudoun County, VA

Summary of Water Resource and Related Data in Loudoun County, VA Prepared by: Loudoun County Department of Building & Development Water Resources Team September, 2008 Loudoun County - Water Resources Data Summary 1 Groundwater Data .................................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.1 Loudoun County Groundwater, Well, and Pollution Sources ......................................................................................................... 3 1.2 USGS Groundwater Wells ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 1.3 County Hydrogeologic Studies ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.4 USGS NAWQA Wells ..................................................................................................................................................................... 3 1.5 WRMP Monitoring Wells................................................................................................................................................................. 3 1.6 Water Quality Data from LCSA and VADH Public Water Supplies ............................................................................................. 3 1.7 Luck Stone Special Exception Water Quality Reports ................................................................................................................... -

Prince William County Tidal Marsh Inventory

W&M ScholarWorks Reports 5-1975 Prince William County Tidal Marsh Inventory Kenneth A. Moore Virginia Institute of Marine Science Gene M. Silberhorn Virginia Institute of Marine Science Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/reports Part of the Terrestrial and Aquatic Ecology Commons Recommended Citation Moore, K. A., & Silberhorn, G. M. (1975) Prince William County Tidal Marsh Inventory. Special Report in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering No. 78. Virginia Institute of Marine Science, College of William and Mary. https://doi.org/10.21220/V55H9H This Report is brought to you for free and open access by W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Reports by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PRINCE WILLIAM COUNTY TIDAL MARSH INVENTORY Special Report No. 78 in Applied Marine Science and Ocean Engineering Kenneth A. Moore G.M. Silberhorn , Project Leader VIRGINIA INSTITUTE OF MARINE SCIENCE Gloucester Point, Virginia 23062 Dr. William J. Hargis, Jr., Director MAY 1975 Acknowledgments Funds for the publication and distribution of this report have been provided by the Department of Commerce, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, Office of Coastal Zone Management, Grant No. 04-5-158-5001. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude to Dr. Gene M. Silberhorn. His invaluable guidance and assistance made this report possible. I wish also to thank Col. George Dawes, for his review of this report and his assistance in the field and Dr. William J. Hargis, Dr. Michael E. Bender, Mr. James Mercer, Mr. Thomas Barnard, Miss Christine Plummer and Mr. -

Difficult Run Bacteria TMDL Action Plan PERMIT NUMBER VAR040064 Submitted To

Difficult Run Bacteria TMDL Action Plan PERMIT NUMBER VAR040064 Submitted to DEQ: Approved 2016 Updated June 2020 CITY OF FAIRFAX, VIRGINIA - DIFFICULT RUN E.COLI TMDL ACTION PLAN INTRODUCTION The City of Fairfax has updated this Difficult Run Bacteria (E. coli) TMDL Action Plan to address the Special Condition for approved local TMDLs (Part II.B) in the City’s MS4 Permit. The original action plan was approved by DEQ in 2016. The City’s approach for updating this Action Plan is based on the requirements listed in the current MS4 General Permit and DEQ’s Draft Local TMDL Action Plan Guidance Document that was released on November 21, 2016. Each of the sections in this Action Plan will address one or more of the required action plan content items as listed on pages 6-8 of DEQ’s Draft Local TMDL Action Plan Guidance Document. TMDL BACKGROUND INFORMATION 1. The name(s) of the Final TMDL report(s); 2. The pollutant(s) causing the impairment(s); 3. The WLA(s) assigned to the MS4 as aggregate or individual WLAs. [This section of the Action Plan directly addresses Part II.B.3.a-c. of the MS4 Permit and DEQ Guidance Document Action Plan Content Items 1-3] The City of Fairfax was assigned an aggregated Waste Load Allocation (WLA) under the approved TMDL report entitled Bacteria TMDL for the Difficult Run Watershed, dated April 25, 2008. The impaired segment of Difficult Run (Segment ID: VAN-A11R-01) begins at the confluence of Captain Hickory Run with Difficult Run and extends 2.93 miles downstream to its confluence with the Potomac River. -

Species: Dwarf Wedgemussel (Alasmidonta Heterodon) Global

Species: Dwarf Wedgemussel (Alasmidonta heterodon) Global Rank: G1G2 State Rank: S1 State Wildlife Action Plan Priority: Immediate Concern Species CCVI Rank: Highly Vulnerable Confidence: Very High Habitat: Dwarf wedgemussels generally live in creek and river bottoms where sand is a component of the substrate (e.g., muddy sand, sand, sand and gravel bottoms), the current is slow to moderate, and there is little silt deposition (USFWS 1993). This species is discontinuously distributed in the Atlantic coast drainages from Maine to North Carolina (NatureServe 2010). Current Threats: Major threats leading to the decline of dwarf wedgemussel include impoundments, pollution, sedimentation, competition from exotic species, population-related problems, and construction projects (USFWS 1993). Main Factors Contributing to Vulnerability Rank: Predicted impact of land use changes designed to mitigate against climate change: Natural gas extraction may alter the water quality of the Delaware River. Dispersal and movement: As adults, the dwarf wedgemussel is mostly non-migratory with only limited vertical movement and possibly passive movement due to flood events (NYNHP 2010). Predicted macro sensitivity to changes in precipitation, hydrology, or moisture regime: Considering the range of the mean annual precipitation across the species’ range in Pennsylvania, the species has experienced a very small precipitation variation in the past 50 years. Dependence on specific disturbance regime likely to be impacted by climate change: More intense flooding events, likely associated with climate change in Pennsylvania, may affect dwarf wedgemussel populations by altering water/habitat quality of rivers and streams (e.g., increased silt load). Dependence on other species for propagule dispersal: Dwarf wedgemussel depends on a few fish (Johnny darter, tessellated darter, and mottled sculpin) to serve as glochidial hosts (Spoo 2008).