Irony, Sarcasm and the Changing Nature of Workplace Resistance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eric Clapton I Shot the Sheriff

I Shot The Sheriff Eric Clapton Ami Dmi Ami 1. I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy Dmi Ami I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy Dmi Emi Ami All around in my home town Dmi Emi Ami They're trying to track me down Dmi Emi Ami They say they want to bring me in guilty Dmi Emi Ami For the killing of a deputy Dmi Emi Ami For the life of a deputy. But I say 2. I shot the sheriff, but I swear it was in self-defense I shot the sheriff, and they say it is a capital offense Sheriff John Brown always hated me For what I don't know Every time that I plant a seed He said "Kill it before it grows" He said "Kill it before it grows" I say! 3. I shot the sheriff, but I swear it was in self-defense I shot the sheriff, but I swear it was in self-defense Freedom came my way one day And I started out of town yeah All of a sudden I see sheriff John Brown Aiming to shoot me down So I shot, I shot him down I say! 4. I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy I shot the sheriff, but I didn't shoot the deputy Reflexes got the better of me And what is to be must be Every day the bucket falls to the well But one day the bottom will drop out Yes, one day the bottom will drop out. -

2021 AKC Master National Qualified Dogs

2021 AKC Master National Qualified Dogs 1,506 as of July 31, 2021 (See below if your dog is not listed.) DOG NAME OWNER BREED 3m Foxy Kona MH J Lane Lab 6bears Chasing The Perfect Storm MH B Berrecloth/S Berrecloth Lab 6bears Gatorpoint Rhea MH B Berrecloth/S Berrecloth Lab 6bears Just Sippin On Sweet Tea MH B Berrecloth/S Berrecloth Lab A Double Shot Of Miss Ellie May MH B Hadley Lab A Legend In Her Own Mind MH K Forehead Lab Abandoned Road's Caffeine Explosion MH MNH4 C Pugh Lab A-Bear For Freedom MH C Kinslow Lab Academy's Buy A Lady A Drink MH T Mitchell NSDTR Academy's Deacon Howl'N Amen MH MNH M Bullen/S Bullen Lab Academy's Pick'Em All Up MH P Dennis Lab Ace Basin’s Last King’s Grant MH R Garmany Lab Ace On The River IV MH MNH M Zamudio Lab Addys Sweet Baby Rae MH D McGraw Lab Adirondac Explorer MH C Lantiegne Golden Adirondac Kuma Yoko MH G Neurohr/N Neurohr Golden Adirondac Tupper Too MH C Lantiegne Golden Agent Natasha Romanova MH G Nichols Lab AHOY Dark Beauty MH R Randleman Lab Aimpowers Captain's Creole Cash MH L Hoover Lab Ajs Labs Once Upon A Time MH A Walters/J Walters Lab Ajs Labs Song Of The South MH J Walters/A Walters Lab AJS Labs Song of the South MH Joel and Anja Walters Lab Ajs Sailor Katy's I Shot The Sheriff MH a walters/j walters Lab Ajs Sailor Katy's Whips And Things MH MNR j walters/a walters Lab Ajtop Chiefs Blessed Beau MH K Jenkins Lab Ajtop Cody's Kajun Pride MH C Billings Lab AJTOP Gold Pearl MH R Loewenstein/J Loewenstein Lab Alabama Moon Bear MH J Gammon CBR Alabama's Rebel Girl MH G Goodman Lab Alabamas -

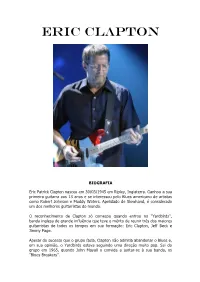

Eric Clapton

ERIC CLAPTON BIOGRAFIA Eric Patrick Clapton nasceu em 30/03/1945 em Ripley, Inglaterra. Ganhou a sua primeira guitarra aos 13 anos e se interessou pelo Blues americano de artistas como Robert Johnson e Muddy Waters. Apelidado de Slowhand, é considerado um dos melhores guitarristas do mundo. O reconhecimento de Clapton só começou quando entrou no “Yardbirds”, banda inglesa de grande influência que teve o mérito de reunir três dos maiores guitarristas de todos os tempos em sua formação: Eric Clapton, Jeff Beck e Jimmy Page. Apesar do sucesso que o grupo fazia, Clapton não admitia abandonar o Blues e, em sua opinião, o Yardbirds estava seguindo uma direção muito pop. Sai do grupo em 1965, quando John Mayall o convida a juntar-se à sua banda, os “Blues Breakers”. Gravam o álbum “Blues Breakers with Eric Clapton”, mas o relacionamento com Mayall não era dos melhores e Clapton deixa o grupo pouco tempo depois. Em 1966, forma os “Cream” com o baixista Jack Bruce e o baterista Ginger Baker. Com a gravação de 4 álbuns (“Fresh Cream”, “Disraeli Gears”, “Wheels Of Fire” e “Goodbye”) e muitos shows em terras norte americanas, os Cream atingiram enorme sucesso e Eric Clapton já era tido como um dos melhores guitarristas da história. A banda separa-se no fim de 1968 devido ao distanciamento entre os membros. Neste mesmo ano, Clapton a convite de seu amigo George Harisson, toca na faixa “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” do White Album dos Beatles. Forma os “Blind Faith” em 1969 com Steve Winwood, Ginger Baker e Rick Grech, que durou por pouco tempo, lançando apenas um album. -

Here’S One in Every Crowd Erlasting Cultural Statement – Everything You Do from a Lot

Hittin’ the Note: Bill, did you feel at all a need to vindicate this period of Clapton’s music? Once you’ve It’s OK; you’re safe with me! photo by Sid Smith been labeled “God” – as Clapton was in what began as graffi ti on a London subway wall and grew into an ev- Well, I actually happen to like There’s One in Every Crowd erlasting cultural statement – everything you do from a lot. I understand why it’s overlooked – there’s no big hit that moment is viewed under a microscope. It seems, on there, and the cover was probably not the most striking. I though, that this particular chapter of Eric’s story has think most people don’t realize the business of the business taken some critical heat over the years. – There’s One In Every Crowd and E.C. Was Here were cut out in 1976 because RSO Records left Atlantic and went to Bill Levenson: I think what I came up against right from Polydor. There was a housecleaning of product, and when the start wasn’t a vindication of the music or the artist − it those records got cut out, they didn’t come into print again was the vindication of the There’s One In Every Crowd and for a decade. People think that they were cut out because E.C. Was Here albums. When people talk about this era, they weren’t good or they weren’t selling, but they were cut they invariably talk about 461 Ocean Boulevard – it was out because distribution stopped on the Atlantic side. -

'Wish' Away the Muggers Sports and Other Shorts

The Arts September 16, 1974, The Retriever, Page 9 'Wish' away the muggers 'Whatever weird things you have heard A drug addict holds him up~ and BLAM! everybody's favorite slugger had just "KILL HIM!" more scream. BLAM! The about "De'ath Wish", starring Charles He kills his first mugger. The audience is belted a three-run homer. kid falls dead as a baseball bat and the Bronson. as the defender of the middle smiling more. He vomits after the murder, Bronson keeps baiting muggers, and I crowd roars with satisfaction. as if class, are probably true. It's an absolute but the sympathetic liberal in him has been keep drinking Mexican beers more ner as if 1 were a boyeur who had stumbled must for every mass psychology student. ~aten away by revenge, and Bronson vously. They're gonna get me, I think. I drunkenly into a private party. The line was a block long on a Wednes \Jecomes the angry anonymous here of the survey the crowd and three-fouths of it is A sensation-hungry press crowns Bron day night when it opened in, Baltimore. I middle class. middle-aged, middle-class, humorless ex son an international hero, but no one ever grabbed an end seat, munched on some I sip my third beer nervously, avoiding cept for their strange laughter to Bronson's discovers his identity. Hail Vigilante! He buttered popcorn and opened a six-pack of the grandmother next to me who's pound revenge killings. singlehandedly cuts the New York City Mexican beer. I studied the faces around ing a big black umbrella into the floor every Like the old sheriff of Old Tuscon, he crime rate in half, from 950 muggings a me. -

Classic Rock/ Metal/ Blues

CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Caught Up In You- .38 Special Girls Got Rhythm- AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long- AC/DC Angel- Aerosmith Rag Doll- Aerosmith Walk This Way- Aerosmith What It Takes- Aerosmith Blue Sky- The Allman Brothers Band Melissa- The Allman Brothers Band Midnight Rider- The Allman Brothers Band One Way Out- The Allman Brothers Band Ramblin’ Man- The Allman Brothers Band Seven Turns- The Allman Brothers Band Soulshine- The Allman Brothers Band House Of The Rising Sun- The Animals Takin’ Care Of Business- Bachman-Turner Overdive You Ain’t Seen Nothing Yet- Bachman-Turner Overdrive Feel Like Makin’ Love- Bad Company Shooting Star- Bad Company Up On Cripple Creek- The Band The Weight- The Band All My Loving- The Beatles All You Need Is Love- The Beatles Blackbird- The Beatles Eight Days A Week- The Beatles A Hard Day’s Night- The Beatles Hello, Goodbye- The Beatles Here Comes The Sun- The Beatles Hey Jude- The Beatles In My Life- The Beatles I Will- Beatles Let It Be- The Beatles Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)- The Beatles Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da- The Beatles Oh! Darling- The Beatles Rocky Raccoon- The Beatles She Loves You- The Beatles Something- The Beatles CLASSIC ROCK/ METAL/ BLUES Ticket To Ride- The Beatles Tomorrow Never Knows- The Beatles We Can Work It Out- The Beatles When I’m Sixty-Four- The Beatles While My Guitar Gently Weeps- The Beatles With A Little Help From My Friends- The Beatles You’ve Got To Hide Your Love Away- The Beatles Johnny B. -

Kevin's Solo Play List

Kevin’s Solo Play List 10cc - I'm Not In Love Ace - How Long (has this been going on) Al Green - Love & Happiness Al Green - Let's Stay Together Al Green - Take Me To The River Alan Parsons Project - Eye In The Sky Alan Parsons Project - Wouldn't Want To Be Like You Alan Parsons Project - Games People Play Allman Brothers - Melissa Allman Brothers - One Way Out Allman Brothers - Statesboro Blues April Wine - Just Between You and Me Atlanta Rhythm Section - So Into You B.B. King - Thrill Is Gone Bad Company - Can't Get Enough Badfinger - No Matter What Ben E. King - Stand By Me Bill Withers - Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers - Lean On Me Billy Joel - Only The Good Die Young Billy Joel - Vienna Waits For You Billy Joel - Honesty Billy Joel - You May Be Right Billy Preston - Will It Go Round In Circles Blondie - The Tide Is High Bobby Caldwell - What You Won't Do For Love Bob Dylan - Knockin' On Heavens Door Bob Marley / Eric Clapton - I Shot The Sheriff Bob Seger - Night Moves Bob Seger - Turn The Page Bob Seger - Against The Wind Boz Skaggs - Lowdown Bruce Springsteen - Fire Bruce Springsteen - Hungry Heart CCR - Down On The Corner CCR - Long As I Can See The Light Cream - Crossroads Cream - Sunshine Of Your Love Crosby Stills Nash - Love The One You're With Crowded House - Something So Strong Delbert McClinton - Givin' It Up For Your Love Delbert McClinton - Shakey Ground Duran Duran - Come Undone Earth Wind & Fire - Shining Star Earth Wind & Fire - Sing A Song Eddie Floyd - Knock On Wood Eddie Money - Baby Hold On Elvis Presley - I Can't -

2020 AKC Master National Qualified Dogs

2020 AKC Master National Qualified Dogs 1.796 as of July 31, 2020 (See below if your dog is not listed.) DOG NAME OWNER BREED 3 Ring Tycho's Supernova Of Tgk MH J Cochran Lab 3m Jazzed That Tequila Sunrise Up MH a mcfatridge Lab A Legend In Her Own Mind MH K Forehead Lab Abandoned Road's Caffeine Explosion MH MNH4 C Pugh Lab ACADEMY'S ALL AMERICAN MH MNH6 T Mitchell Lab Academy's Buy a Lady a Drink MH T Mitchell Lab Academy's Deacon Howl'N Amen MH MNH M Bullen/S Bullen Lab Academys Good Golly Miss Molly MH D Brett/L Brett Lab Academy's Shoot 'Em Down Turn Around MH B Walizer Lab Ace Basin's Last King's Grant MH R Garmany Lab Ace On The River IV MH MNH M Zamudio Lab Acedo's Maya RE MH AX AXJ CGC TKN M Acedo Lab Adams Acres Fetchem Up Full Choke MH D Biggert Lab Addie Girl Andrus MH J Andrus Lab Addi's Big Debut MH M Bice Lab Adirondac High Speed Chase MH C Lantiegne Golden Adirondac Lake Effect MH CCA C Lantiegne Golden Agent Natasha Romanova MH Gordon Nichols Lab AimPowers Captain's Creole Cash MH Linda Hoover Lab Aimpowers Roxie's Blue Bonnet MH L Hoover Lab Ain't Whistling "Dixie" Bell MH MNH J Gisclair Lab AJAX'S JACOB'S SHOT OF BLACK POWDER MH MNH4 E RISCHKA Lab Ajax's Teufel Hunden MH QAA J BURCH Lab Ajs Labs Once Upon A Time MH Anya Walters, Joel Walters Lab Ajs Sailor Katy's I Shot The Sheriff MH a walters/j walters Lab Ajs Sailor Katy's Whips And Things MH j walters/a walters Lab Ajtop Chiefs Blessed Beau MH K Jenkins Lab Ajtop Cody's Kajun Pride MH C Billings Lab Akk's Main Mankota MH B Franklin Lab Aks's "Gunner" Kasey Engrassia -

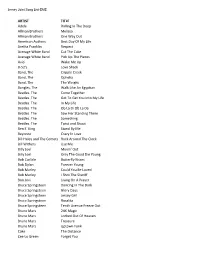

Jersey Joint Song List-EME

Jersey Joint Song List-EME ARTIST TITLE Adele Rolling In The Deep Allman Brothers Melissa Allman Brothers One Way Out American Authors Best Day Of My Life Aretha Franklin Respect Average White Band Cut The Cake Average White Band Pick Up The Pieces Avici Wake Me Up B-52's Love Shack Band, The Cripple Creek Band, The Ophelia Band, The The Weight Bangles, The Walk Like An Egyptian Beatles. The Come Together Beatles. The Got To Get You Into My Life Beatles. The In My Life Beatles. The Ob La Di Ob La Da Beatles. The Saw Her Standing There Beatles. The Something Beatles. The Twist and Shout Ben E. King Stand By Me Beyonce Crazy In Love Bill Haley and The Comets Rock Around The Clock Bill Withers Use Me Billy Joel Movin' Out Billy Joel Only The Good Die Young Bob Carlisle Butterfly Kisses Bob Dylan Forever Young Bob Marley Could You Be Loved Bob Marley I Shot The Sheriff Bon Jovi Living On A Prayer Bruce Springsteen Dancing In The Dark Bruce Springsteen Glory Days Bruce Springsteen Jersey Girl Bruce Springsteen Rosalita Bruce Springsteen Tenth Avenue Freeze Out Bruno Mars 24K Magic Bruno Mars Locked Out Of Heaven Bruno Mars Treasure Bruno Mars Uptown Funk Cake The Distance Cee Lo Green Forget You Jersey Joint Song List-EME Contours, The Do You Love Me Cupid Cupid Shuffle Daft Punk Get Lucky Dion Runaround Sue DNCE Cake By The Ocean Dusty Springfield Son Of A Preacher Man Eagles, The One of These Nights Earth Wind and Fire September Ed Sheeran Shape of You Elvis Presley A Little Less Conversation Etta James At Last Frank Sinatra Fly Me To The -

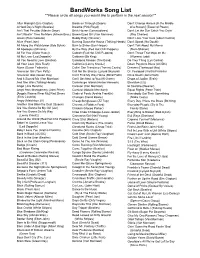

Bandworks Song List **Please Circle All Songs You Would Like to Perform in the Next Session**

BandWorks Song List **Please circle all songs you would like to perform in the next session** After Midnight (Eric Clapton) Break on Through (Doors) Don’t Change Horses [In the Middle A Hard Day’s Night (Beatles) Breathe (Pink Floyd) of a Stream] (Tower of Power) Ain’t That Peculiar (Marvin Gaye) Brick House (Commodores) Don’t Let the Sun Catch You Cryin’ Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More (Allman Bros.) Brown-Eyed Girl (Van Morrison) (Ray Charles) Alison (Elvis Costello) Buddy Holly (Weezer) Don’t Lose Your Cool (Albert Collins) Alive (Pearl Jam) Burning Down the House (Talking Heads) Don’t Speak (No Doubt) All Along the Watchtower (Bob Dylan) Burn to Shine (Ben Harper) Don’t Talk About My Mama All Apologies (Nirvana) By the Way (Red Hot Chili Peppers) (Mem Shanon) All For You (Sister Hazel) Cabron (Red Hot Chili Peppers) Don’t Throw That Mojo on Me All My Love (Led Zeppelin) Caldonia (Bb King) (Wynona Judd) All You Need Is Love (Beatles) Caledonia Mission (The Band) Do Your Thing (Lyn Collins) All Your Love (Otis Rush) California (Lenny Kravitz) Down Payment Blues (AC/DC) Alone (Susan Tedeschi) Callin’ San Francisco (Tommy Castro) Dreams (Fleetwood Mac) American Girl (Tom Petty) Call Me the Breeze (Lynyrd Skynyrd) Dr. Feelgood (Aretha Franklin) American Idiot (Green Day) Can’t Find My Way Home (Blind Faith) Drive South (John Hiatt) And It Stoned Me (Van Morrison) Can’t Get Next to You (Al Green) Drops of Jupiter (Train) And She Was (Talking Heads) Canteloupe Island (Herbie Hancock) Elevation (U2) Angel (Jimi Hendrix) Caravan (Van Morrison) -

Robin and the Sherwood Hoodies Script 151213

Robin And The Sherwood Hoodies Junior Script by Craig Hawes 1/160114/9 ISBN: 978 1 84237 147 3 Published by Musicline Publications P.O. Box 15632 Tamworth Staffordshire B77 5BY 01827 281 431 www.musiclinedirect.com No part of this publication may be transmitted, stored in a retrieval system, or reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, manuscript, typesetting, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owners. It is an infringement of the copyright to give any public performance or reading of this show either in its entirety or in the form of excerpts, whether the audience is charged an admission or not, without the prior consent of the copyright owners. Dramatic musical works do not fall under the licence of the Performing Rights Society. Permission to perform this show from the publisher ‘MUSICLINE PUBLICATIONS’ is always required. An application form, for permission to perform, is supplied at the back of the script for this purpose. To perform this show without permission is strictly prohibited. It is a direct contravention of copyright legislation and deprives the writers of their livelihood. Anyone intending to perform this show should, in their own interests, make application to the publisher for consent, prior to starting rehearsals. All Rights Strictly Reserved. Robin And The Sherwood Hoodies 1 CONTENTS Cast List ................................................................................................................................ 3 Speaking Roles by Number -

I Shot the Sheriff Chords and Lyrics Eric Clapton

I Shot The Sheriff Chords And Lyrics Eric Clapton Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy D# Dm Gm D# Dm Gm All around in my home town - They're trying to track me down D# Dm Gm They say they want to bring me in guilty D# Dm Gm For the killing of a deputy D# Dm Gm For the life of a deputy ------ But I say Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I swear it was in self-defense Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, and they say it is a capital offense D# Dm Gm D# Dm Gm Sheriff John Brown always hated me - For what I don't know D# Dm Gm Every time - that I plant a seed D# Dm Gm He said, "Kill it before it grows D# Dm Gm He said, "Kill it before it grows - I say Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I swear it was in self-defense Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I swear it was in self-defense http://www.kirbyscovers.com D# Dm Gm D# Dm Gm Freedom came my way one day - And I started out of town D# Dm Gm All of a sudden I see sheriff John Brown D# Dm Gm Aiming to shoot me down D# Dm Gm So I shot - I shot him down - I say Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy D# Dm Gm D# Dm Gm Reflexes got the better of me - And what is to be must be D# Dm Gm Every day the bucket goes to the well D# Dm Gm But one day the bottom will drop out D# Dm Gm Yes, one day the bottom will drop out - But I say Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot the deputy Gm Cm Gm I shot the sheriff, but I did not shoot no deputy D# Dm Gm (x4) http://www.kirbyscovers.com .