National Collegiate Athletic Association, Random Drug-Testing, and the Applicability of the Administrative Search Exception

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Steroid Use in Sports, Part Ii: Examining the National Football League’S Policy on Anabolic Steroids and Related Sub- Stances

STEROID USE IN SPORTS, PART II: EXAMINING THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE’S POLICY ON ANABOLIC STEROIDS AND RELATED SUB- STANCES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 27, 2005 Serial No. 109–21 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 21–242 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:42 Jun 28, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\21242.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM TOM DAVIS, Virginia, Chairman CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut HENRY A. WAXMAN, California DAN BURTON, Indiana TOM LANTOS, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida MAJOR R. OWENS, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois CHRIS CANNON, Utah WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee DIANE E. WATSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland DARRELL E. ISSA, California LINDA T. -

2013 Steelers Media Guide 5

history Steelers History The fifth-oldest franchise in the NFL, the Steelers were founded leading contributors to civic affairs. Among his community ac- on July 8, 1933, by Arthur Joseph Rooney. Originally named the tivities, Dan Rooney is a board member for The American Ireland Pittsburgh Pirates, they were a member of the Eastern Division of Fund, The Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation and The the 10-team NFL. The other four current NFL teams in existence at Heinz History Center. that time were the Chicago (Arizona) Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, MEDIA INFORMATION Dan Rooney has been a member of several NFL committees over Chicago Bears and New York Giants. the past 30-plus years. He has served on the board of directors for One of the great pioneers of the sports world, Art Rooney passed the NFL Trust Fund, NFL Films and the Scheduling Committee. He was away on August 25, 1988, following a stroke at the age of 87. “The appointed chairman of the Expansion Committee in 1973, which Chief”, as he was affectionately known, is enshrined in the Pro Football considered new franchise locations and directed the addition of Hall of Fame and is remembered as one of Pittsburgh’s great people. Seattle and Tampa Bay as expansion teams in 1976. Born on January 27, 1901, in Coultersville, Pa., Art Rooney was In 1976, Rooney was also named chairman of the Negotiating the oldest of Daniel and Margaret Rooney’s nine children. He grew Committee, and in 1982 he contributed to the negotiations for up in Old Allegheny, now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side, and the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the NFL and the Players’ until his death he lived on the North Side, just a short distance Association. -

The National Collegiate Athletic Association, Random Drug-Testing

Hofstra Law Review Volume 17 | Issue 3 Article 4 1989 The aN tional Collegiate Athletic Association, Random Drug-Testing, and the Applicability of the Administrative Search Exception Craig H. Thaler Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Thaler, Craig H. (1989) "The aN tional Collegiate Athletic Association, Random Drug-Testing, and the Applicability of the Administrative Search Exception," Hofstra Law Review: Vol. 17: Iss. 3, Article 4. Available at: http://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/hlr/vol17/iss3/4 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thaler: The National Collegiate Athletic Association, Random Drug-Testing NOTE THE NATIONAL COLLEGIATE ATHLETIC ASSOCIATION, RANDOM DRUG-TESTING, AND THE APPLICABILITY OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE SEARCH EXCEPTION It is not unreasonable to set traps to keep foxes from entering hen houses even in the absence of evidence of prior vulpine intrusion or individualized suspicion that a particularfox has an appetite for chickens.1 Honorable Alvin B. Rubin I. INTRODUCTION At the Eightieth National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA)2 convention, the NCAA instituted a detailed drug-testing program3 authorizing the NCAA Executive Committee to drug test student-athletes who compete in NCAA championships and certified I. National Treasury Employees Union v. Von Raab, 816 F.2d 170, 179 (5th Cir. 1987), affid, 109 S.Ct. 1384 (1989). -

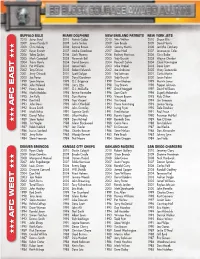

Afc East Afc West Afc East Afc

BUFFALO BILLS MIAMI DOLPHINS NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS NEW YORK JETS 2010 Jairus Byrd 2010 Patrick Cobbs 2010 Wes Welker 2010 Shaun Ellis 2009 James Hardy III 2009 Justin Smiley 2009 Tom Brady 2009 David Harris 2008 Chris Kelsay 2008 Ronnie Brown 2008 Sammy Morris 2008 Jerricho Cotchery 2007 Kevin Everett 2007 Andre Goodman 2007 Steve Neal 2007 Laveranues Coles 2006 Takeo Spikes 2006 Zach Thomas 2006 Rodney Harrison 2006 Chris Baker HHH 2005 Mark Campbell 2005 Yeremiah Bell 2005 Tedy Bruschi 2005 Wayne Chrebet 2004 Travis Henry 2004 David Bowens 2004 Rosevelt Colvin 2004 Chad Pennington 2003 Pat Williams 2003 Jamie Nails 2003 Mike Vrabel 2003 Dave Szott 2002 Tony Driver 2002 Robert Edwards 2002 Joe Andruzzi 2002 Vinny Testaverde 2001 Jerry Ostroski 2001 Scott Galyon 2001 Ted Johnson 2001 Curtis Martin 2000 Joe Panos 2000 Daryl Gardener 2000 Tedy Bruschi 2000 Jason Fabini 1999 Sean Moran 1999 O.J. Brigance 1999 Drew Bledsoe 1999 Marvin Jones 1998 John Holecek 1998 Larry Izzo 1998 Troy Brown 1998 Pepper Johnson 1997 Henry Jones 1997 O.J. McDuffie 1997 David Meggett 1997 David Williams 1996 Mark Maddox 1996 Bernie Parmalee 1996 Sam Gash 1996 Siupeli Malamala 1995 Jim Kelly 1995 Dan Marino 1995 Vincent Brown 1995 Kyle Clifton 1994 Kent Hull 1994 Troy Vincent 1994 Tim Goad 1994 Jim Sweeney AFC EAST 1993 John Davis 1993 John Offerdahl 1993 Bruce Armstrong 1993 Lonnie Young 1992 Bruce Smith 1992 John Grimsley 1992 Irving Fryar 1992 Dale Dawkins 1991 Mark Kelso 1991 Sammie Smith 1991 Fred Marion 1991 Paul Frase 1990 Darryl Talley 1990 Liffort Hobley -

We're from the Town with the Great Football Team

WE‟RE FROM THE TOWN WITH THE GREAT FOOTBALL TEAM: A PITTSBURGH STEELERS MANIFESTO By David Villiotti June 2009 1 To… Idie, Anthony & “Mrs. Swiss” ...tolerating my mania Tony …infecting me with Steelers Fever Mom …see Line 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preface 4 January, 2008 7 Behind Enemy Lines 8 Family of Origin…Swissvale 13 The Early Years: Pitt Stadium Days 18 Forbes Field Memories 28 Other Burgh Sports 34 Tony 38 Rest of The Boys 43 1970s: Unparallelled 46 Why Roy Gerela 64 1980s: Dark Decade 68 Why Mrs. Swiss Hates the Steelers 79 Stuff I Hate about the NFL 83 „90s: Changing of the Guard 87 Heckling 105 Family Gatherings 108 Taping 111 Rooting for Injuries 115 13 Minutes Ain‟t Enuff 120 Y2K Decade: First Five Years…Still Waiting 124 One For The Thumb 133 Cowher Out…Tomlin In 140 Steelers Trivia Challenge 145 Steelers Sites: Mill, Fury, Spiker, et al 149 Six!!! 156 City of Champions 209 Closing 214 *From “The Steelers Polka” by Jimmy Psihoulis 3 PREFACE Having catalogued my life by the ups and downs of the Pittsburgh Steelers Football Club, and having surpassed the half century mark in age, I endeavored to author a memoir of my life as a fan. This perhaps would be suited for a time capsule for my children, or alternatively as a project for a publisher whose business was really, really slow. For the past few years, I‟ve written a number of articles, under the screen name, Swissvale72 for a few Pittsburgh Steelers related websites, most notably, and of longest duration, was an association with Stillers.com, prior to my falling into disfavor with management. -

Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame

Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame 6th Induction Ceremony Friday November 25, 2016 Langley’s Restaurant at Great Neck Country Club Waterford, Connecticut Platinum Sponsor The Mortimer Family and The Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame would like to thank the Mortimer family and GNCC for their wonderful support of our efforts to honor those who have made special contributions to Waterford athletics. In addition to helping us with the induction ceremony, their support helped us reach a goal of a permanent location to honor the members of the Hall of Fame. A perpetual plaque is now displayed outside the Francis X. Sweeney Field House at Waterford High School to serve as a lasting memory of the inductees. 2016 Induction Ceremony - Program of Events 6:00 PM Social Hour 7:00 PM Welcome Jim Cavalieri, HOF Committee Chair 7:15 PM Hall of Fame Inductions/Honorees Aaron Curry Stephen Harper Bridgit (Lawrence) Buscetto Joe Miller Kris Morton Rick Murallo Chris Podeszwa Katie Schoepfer The Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame The Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame was founded in 2002 by The Cactus Jack Foundation to honor those who have made special contributions to Waterford athletics, as a player, coach, administrator or community volunteer. Class of 2002 Class of 2004 Howard Christensen Bill Gardner Sr. Richard Cipriani Arnold Holm Gerard Rousseau Jan Merrill Morin Francis X. Sweeney Gary Swanson Joan Van Ness Class of 2008 Class of 2010 Ron Bugbee Marlene (Morth) Wiggins Joe Carey Liz Mueller Karen Mullins Glenn Rupert Gene Sutera David Sousa Norman Tonucci Warren Swanson Class of 2014 Lee Elci Ed Evento Billy Gardner Jr. -

Vernon Zoners Hear Objections to Condo Policy by BARBARA RICHMOND the Amendments, As Proposed by the PRD Zone

2 0 - EVENING HERALD, Fri,, Jan. 18, 1980 Vernon Zoners Hear Objections to Condo Policy By BARBARA RICHMOND The amendments, as proposed by the PRD zone. He said his clients property area, Daniel Walker, said concern about this saying they chose part of the special permit process or HrralH Rrporirr Kunzli include provisions for con own a parcel of land in a PRD zone he could count on one hand the to live in an apartment and cannot af the permit need not be granted. dominium conversions of existing VERNON — There were many and want to build condominiums on number of people who want con ford to buy a condominium for ateut Kunzli said the condominium con You Can Be a Winner! objections, some stronger than apartments. it. Right now the zoning laws require dominiums in town. $40,000. version issue is much more complex Some lucky couple will win a trip to Florida and spend The Planning Commission at least five acres of land in the PRD He cited the fact that the Towns of A statement written by Kunzli and iiaurhpfitpr others, at a public hearing of the and difficult than that of new con four days and three nights at the Sonesta Beach Hotel in Zoning Commission Thursday night, recommended that the Zoning Com zones. The proposed laws would Manchester and Coventry are presented by John Loranger, plan struction. "The extensive hearing Key Biscayne. The Herald, in cooperation with the mission approve the amendment for change this to three acres. fighting HUD. He said also there on zone changes that would allow ning consultant, stressed the fact process as well as the commission's LaBonne Travel Agency and participating merchants, is new condominiums but said it wasn't Martin Luginbuhl, a local should be a different set of that there is a housing shortage ail rules of procedure permit adoption of condominium construction and con offering the Florida trip. -

Performance Enhancing Drugs in Sports Fast Facts

Running head: STEROIDS IN SPORTS 1 Performance-Enhancing Drugs in Professional Sports and Eliminating Anabolic Steroids Katlyn Fenuccio Lasell College, Auburndale, MA STEROIDS IN SPORTS 2 Abstract Anabolic steroids, famous as performance-enhancement drugs, are synthetic derivatives of testosterone, modified to enhance its anabolic actions (promotion of protein synthesis and muscle cell growth). Athletes use anabolic steroids during competition to increase muscle mass and overall athletic performance. Using these substances unfold adverse physical, psychological, and behavioral consequences. Aside from harmful side effects, laws must be in place prohibiting steroid use in all sports and levels of competition. Research has provided sufficient evidence supporting steroid prohibition in athletics. Keywords: anabolic steroids, testosterone, doping, performance-enhancing drugs (PED) STEROIDS IN SPORTS 3 Performance-Enhancing Drugs in Professional Sports and Eliminating Anabolic Steroids Even before sports were televised, controversy about the use of steroids for performance enhancement was a hot topic. Professional athletes in particular, are constantly looking for new ways to one up their opponents during competition. Among these tactics is the illegal use of anabolic steroids. When it comes to winning, professional athletes will risk it all despite the inevitable consequences. Comprehensive research and experimental results provide clear evidence that professional athletes should not be allowed to use anabolic steroids for performance enhancing purposes because the use of steroids negatively alter both the physical and psychological health of the athlete, children’s perception of an ideal role model, and the integrity of the game itself. Anabolic-androgenic steroids, better known as anabolic steroids, are synthetic derivatives of testosterone, modified by individuals for athletic performance enhancement purposes. -

Willie Richardson Jimmy Orr Alex Hawkins Ray Perkins Gail Cogdill

APBA Great Teams of the Past Football Season Card Set Volume 1 The following players comprise the Great team of the Past Vol. 1 APBA Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most frequently. Realistic use of the players below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the number there for the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he recovers a fumble. 1942 CHICAGO 1950 CLEVELAND 1962 GREEN BAY 1968 BALTIMORE OFFENSE OFFENSE OFFENSE OFFENSE Wide Receiver: John Siegel Wide Receiver: Mac Speedie Wide Receiver: Boyd Dowler PA Wide Receiver: Willie Richardson George Wilson Dante Lavelli Max McGee PB Jimmy Orr Hampton Pool Horace Gillom OC PA Gary Barnes Alex Hawkins Connie Mack Berry George Young Tackle: Bob Skoronski Ray Perkins Bob Nowaskey Tackle: Lou Groza KA KOA Forrest Gregg Gail Cogdill Clint Wager Lou Rymkus OC Norm Masters Tackle: Bob Vogel Tackle: Ed Kolman Chubby Gregg KB KOB Guard: Fuzzy Thurston Sam Ball Lee Artoe KB KOB John Sanusky Jerry Kramer KA KOA John Williams Joe Stydahar KB KOB John Kissell Ed Blaine Guard: Glenn Ressler Bill Hempel Guard: Weldon Humble Center: Jim Ringo Dan Sullivan Al Hoptowit Lin -

Super Bowl Championship Squad

SUPER BOWL CHAMPIONSHIP SQUAD Green Bay Packers Super Bowl I Champions 5 Paul Hornung 12 Zeke Bratkowski 15 Bart Starr (MVP) 21 Bob Jeter 22 Elijah Pitts 24 Willie Wood 26 Herb Adderley 27 Red Mack 31 Jim Taylor 33 Jim Grabowski 34 Don Chandler 37 Phil Vandersea 40 Tom Brown 43 Doug Hart 44 Donny Anderson 45 Dave Hathcock 50 Bill Curry 56 Tommy Crutcher 57 Ken Bowman 60 Lee Roy Caffey 63 Fred Thurston 64 Jerry Kramer 66 Ray Nitschke 68 Gale Gillingham 72 Steve Wright 73 Jim Weatherwax 74 Henry Jordan 75 Forrest Gregg 76 Bob Skoronski 77 Ron Kostelnik 78 Bob Brown 80 Bob Long 81 Marv Fleming 82 Lionel Aldridge 84 Carroll Dale 85 Max McGee 86 Boyd Dowler 87 Willie Davis 88 Bill Anderson 89 Dave Robinson Head Coach: Vince Lombardi Coaches: Phil Bengtson, Jerry Burns, Red Cochran, Dave Hanner, Bob Schnelker, Ray Wietecha Green Bay Packers Super Bowl II Champions 12 Zeke Bratkowski 13 Don Horn 15 Bart Starr (MVP) 21 Bob Jeter 23 Travis Williams 24 Willie Wood 26 Herb Adderley 30 Chuck Mercein 33 Jim Grabowski 34 Don Chandler 36 Ben Wilson 40 Tom Brown 43 Doug Hart 44 Donny Anderson 45 John Rowser 50 Bob Hyland 55 Jim Flanigan 56 Tommy Crutcher 57 Ken Bowman 60 Lee Roy Caffey 63 Fred Thurston 64 Jerry Kramer 66 Ray Nitschke 68 Gale Gillingham 72 Steve Wright 73 Jim Weatherwax 74 Henry Jordan 75 Forrest Gregg 76 Bob Skoronski 77 Ron Kostelnik 78 Bob Brown 80 Bob Long 81 Marv Fleming 82 Lionel Aldridge 83 Allen Brown 84 Carroll Dale 85 Max McGee 86 Boyd Dowler 87 Willie Davis 88 Dick Capp 89 Dave Robinson Head Coach: Vince Lombardi Coaches: Phil -

Researching the Law of Sports: a Revised and Comprehensive Bibliography of Law-Related Materials Frank G

Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal Volume 13 | Number 3 Article 7 1-1-1991 Researching the Law of Sports: A Revised and Comprehensive Bibliography of Law-Related Materials Frank G. Houdek Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/ hastings_comm_ent_law_journal Part of the Communications Law Commons, Entertainment, Arts, and Sports Law Commons, and the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Frank G. Houdek, Researching the Law of Sports: A Revised and Comprehensive Bibliography of Law-Related Materials, 13 Hastings Comm. & Ent. L.J. 589 (1991). Available at: https://repository.uchastings.edu/hastings_comm_ent_law_journal/vol13/iss3/7 This Special Feature is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hastings Communications and Entertainment Law Journal by an authorized editor of UC Hastings Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Researching the Law of Sports: A Revised and Comprehensive Bibliography of Law-Related Materialst by FRANK G. HOUDEK* Table of Contents I. B ooks .................................................... 594 II. Periodicals ................................................ 606 III. Government Publications ................................. 607 A. Professional Sports Generally ......................... 607 B. Antitrust and Professional Team Sports ............... 609 C. Broadcasting and Professional Sports ................. -

Appears on a Players Card, It Means That You Use the K Or P Column When He Reovers a Fumble

1981 APBA PRO FOOTBALL SET ROSTER The following players comprise the 1981 season APBA Pro Football Player Card Set. The regular starters at each position are listed first and should be used most. Realistic use of the players frequently below will generate statistical results remarkably similar to those from real life. IMPORTANT: When a Red "K" appears in the R-column as the result on any kind of running play from scrimmage or on any return, roll the dice again, refer to the K-column, and use the the result. When a player has a "K" in his R-column, he can never be used for kicking or punting. If the symbol "F-K" or "F-P" appears on a players card, it means that you use the K or P column when he reovers a fumble. Players in bold are starters. The number in ()s after the player name is the number of cards that the player has in this set. See below for a more detailed explanation of new symbols on the cards. ATLANTA BALTIMORE BUFFALO CHICAGO OFFENSE OFFENSE OFFENSE OFFENSE EB: Wallace Francis EB: Ray Butler EB: Jerry Butler EB: Brian Baschnagel OC Alfred Jenkins Roger Carr Frank Lewis Rickey Watts Alfred Jackson Brian DeRoo Byron Franklin TC OA Marcus Anderson OC Reggie Smith TB OB Randy Burke Ron Jessie Ken Margerum Tackle: Mike Kenn David Shula TA TB OC Lou Piccone TB OC Tackle: Keith Van Horne Warren Bryant Kevin Williams OB Tackle: Joe Devlin Ted Albrecht Eric Sanders Tackle: Jeff Hart Ken Jones Dan Jiggetts Guard: R.C.