The National Collegiate Athletic Association, Random Drug-Testing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CINCINNATI BENGALS (2-3) Sunday, Oct

PITTSBURGH STEELERS COMMUNICATIONS Burt Lauten - Director of Communications Dominick Rinelli - Public Relations/Media Manager PITTSBURGH STEELERS Angela Tegnelia - Public Relations Assistant 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 www.steelers.com PITTSBURGH STEELERS (4-2) vs. CINCINNATI BENGALS (2-3) Sunday, Oct. 22, 2017 • 4:25 p.m. (ET) • Heinz Field • Pittsburgh, Pa. REGULAR SEASON GAME #7 PITTSBURGH STEELERS Pittsburgh Steelers (4-2) 2017 SCHEDULE vs. PRESEASON (3-1) Cincinnati Bengals (2-3) Friday, Aug. 11 @ New York Giants W, 20-12 (KDKA) Sunday, Aug. 20 ATLANTA W, 17-13 (KDKA) DATE: Sunday, Oct. 22, 2017 | KICKOFF: 4:25 p.m. ET Saturday, Aug. 26 INDIANAPOLIS L, 19-15 (KDKA) SITE: Heinz Field (68,400) • Pittsburgh, Pa. Thursday, Aug. 31 @ Carolina W, 17-14 (KDKA) PLAYING SURFACE: Natural Grass TV COVERAGE: CBS (locally KDKA-TV, channel 2) REGULAR SEASON (4-2) ANNOUNCERS: Jim Nantz (play-by-play) Sunday, Sept. 10 @ Cleveland W, 21-18 (CBS) Tony Romo (analyst) | Tracy Wolfson (sideline) Sunday, Sept. 17 MINNESOTA W, 26-9 (FOX) Sunday, Sept. 24 @ Chicago L, 23-17 OT (CBS) LOCAL RADIO: Steelers Radio Network Sunday, Oct. 1 @ Baltimore W, 26-9 (CBS) WDVE-FM (102.5)/WBGG-AM (970) Sunday, Oct. 8 JACKSONVILLE L, 30-9 (CBS) ANNOUNCERS: Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sunday, Oct. 15 @ Kansas City W, 19-13 (CBS) Tunch Ilkin (analyst) | Craig Wolfl ey (sideline) Sunday, Oct. 22 CINCINNATI 4:25 p.m. (CBS) Sunday, Oct. 29 @ Detroit* 8:30 p.m. (NBC) A LOOK AT THE COACHES Sunday, Nov. -

KANSAS CITY CHIEFS (5-0) Sunday, Oct

PITTSBURGH STEELERS COMMUNICATIONS Burt Lauten - Director of Communications Dominick Rinelli - Public Relations/Media Manager PITTSBURGH STEELERS Angela Tegnelia - Public Relations Assistant 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 www.steelers.com PITTSBURGH STEELERS (3-2) at KANSAS CITY CHIEFS (5-0) Sunday, Oct. 15, 2017 • 4:25 p.m. (ET) • Arrowhead Stadium • Kansas City, Mo. REGULAR SEASON GAME #6 PITTSBURGH STEELERS Pittsburgh Steelers (3-2) 2017 SCHEDULE at PRESEASON (3-1) Kansas City Chiefs (5-0) Friday, Aug. 11 @ New York Giants W, 20-12 (KDKA) Sunday, Aug. 20 ATLANTA W, 17-13 (KDKA) DATE: Sunday, Oct. 15, 2017 | KICKOFF: 4:25 p.m. ET Saturday, Aug. 26 INDIANAPOLIS L, 19-15 (KDKA) SITE: Arrowhead Stadium (76,416) • Kansas City, Mo. Thursday, Aug. 31 @ Carolina W, 17-14 (KDKA) PLAYING SURFACE: Grass TV COVERAGE: CBS (locally KDKA-TV, channel 2) REGULAR SEASON (3-2) ANNOUNCERS: Jim Nantz (play-by-play) Sunday, Sept. 10 @ Cleveland W, 21-18 (CBS) Tony Romo (analyst) | Tracy Wolfson (sideline) Sunday, Sept. 17 MINNESOTA W, 26-9 (FOX) Sunday, Sept. 24 @ Chicago L, 23-17 OT (CBS) LOCAL RADIO: Steelers Radio Network Sunday, Oct. 1 @ Baltimore W, 26-9 (CBS) WDVE-FM (102.5)/WBGG-AM (970) Sunday, Oct. 8 JACKSONVILLE L, 30-9 (CBS) ANNOUNCERS: Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sunday, Oct. 15 @ Kansas City 4:25 p.m. (CBS) Tunch Ilkin (analyst) | Craig Wolfl ey (sideline) Sunday, Oct. 22 CINCINNATI* 1 p.m. (CBS) NATIONAL RADIO: Westwood One Sunday, Oct. 29 @ Detroit* 8:30 p.m. (NBC) ANNOUNCERS: Tom McCarthy (play-by-play) Sunday, Nov. -

Steroid Use in Sports, Part Ii: Examining the National Football League’S Policy on Anabolic Steroids and Related Sub- Stances

STEROID USE IN SPORTS, PART II: EXAMINING THE NATIONAL FOOTBALL LEAGUE’S POLICY ON ANABOLIC STEROIDS AND RELATED SUB- STANCES HEARING BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED NINTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION APRIL 27, 2005 Serial No. 109–21 Printed for the use of the Committee on Government Reform ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.gpo.gov/congress/house http://www.house.gov/reform U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 21–242 PDF WASHINGTON : 2005 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2250 Mail: Stop SSOP, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate 11-MAY-2000 11:42 Jun 28, 2005 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 D:\DOCS\21242.TXT HGOVREF1 PsN: HGOVREF1 COMMITTEE ON GOVERNMENT REFORM TOM DAVIS, Virginia, Chairman CHRISTOPHER SHAYS, Connecticut HENRY A. WAXMAN, California DAN BURTON, Indiana TOM LANTOS, California ILEANA ROS-LEHTINEN, Florida MAJOR R. OWENS, New York JOHN M. MCHUGH, New York EDOLPHUS TOWNS, New York JOHN L. MICA, Florida PAUL E. KANJORSKI, Pennsylvania GIL GUTKNECHT, Minnesota CAROLYN B. MALONEY, New York MARK E. SOUDER, Indiana ELIJAH E. CUMMINGS, Maryland STEVEN C. LATOURETTE, Ohio DENNIS J. KUCINICH, Ohio TODD RUSSELL PLATTS, Pennsylvania DANNY K. DAVIS, Illinois CHRIS CANNON, Utah WM. LACY CLAY, Missouri JOHN J. DUNCAN, JR., Tennessee DIANE E. WATSON, California CANDICE S. MILLER, Michigan STEPHEN F. LYNCH, Massachusetts MICHAEL R. TURNER, Ohio CHRIS VAN HOLLEN, Maryland DARRELL E. ISSA, California LINDA T. -

2013 Steelers Media Guide 5

history Steelers History The fifth-oldest franchise in the NFL, the Steelers were founded leading contributors to civic affairs. Among his community ac- on July 8, 1933, by Arthur Joseph Rooney. Originally named the tivities, Dan Rooney is a board member for The American Ireland Pittsburgh Pirates, they were a member of the Eastern Division of Fund, The Pittsburgh History and Landmarks Foundation and The the 10-team NFL. The other four current NFL teams in existence at Heinz History Center. that time were the Chicago (Arizona) Cardinals, Green Bay Packers, MEDIA INFORMATION Dan Rooney has been a member of several NFL committees over Chicago Bears and New York Giants. the past 30-plus years. He has served on the board of directors for One of the great pioneers of the sports world, Art Rooney passed the NFL Trust Fund, NFL Films and the Scheduling Committee. He was away on August 25, 1988, following a stroke at the age of 87. “The appointed chairman of the Expansion Committee in 1973, which Chief”, as he was affectionately known, is enshrined in the Pro Football considered new franchise locations and directed the addition of Hall of Fame and is remembered as one of Pittsburgh’s great people. Seattle and Tampa Bay as expansion teams in 1976. Born on January 27, 1901, in Coultersville, Pa., Art Rooney was In 1976, Rooney was also named chairman of the Negotiating the oldest of Daniel and Margaret Rooney’s nine children. He grew Committee, and in 1982 he contributed to the negotiations for up in Old Allegheny, now known as Pittsburgh’s North Side, and the Collective Bargaining Agreement for the NFL and the Players’ until his death he lived on the North Side, just a short distance Association. -

CLEVELAND BROWNS (0-15) Sunday, Dec

PITTSBURGH STEELERS COMMUNICATIONS Burt Lauten - Director of Communications Dominick Rinelli - Public Relations/Media Manager PITTSBURGH STEELERS Angela Tegnelia - Public Relations Assistant 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 www.steelers.com PITTSBURGH STEELERS (12-3) vs. CLEVELAND BROWNS (0-15) Sunday, Dec. 31, 2017 • 1 p.m. (ET) • Heinz Field • Pittsburgh, Pa. REGULAR SEASON GAME #16 PITTSBURGH STEELERS 2017 SCHEDULE Pittsburgh Steelers (12-3) vs. PRESEASON (3-1) Cleveland Browns (0-15) Friday, Aug. 11 @ New York Giants W, 20-12 (KDKA) Sunday, Aug. 20 ATLANTA W, 17-13 (KDKA) DATE: Sunday, Dec. 31, 2017 | KICKOFF: 1 p.m. ET Saturday, Aug. 26 INDIANAPOLIS L, 19-15 (KDKA) SITE: Heinz Field (68,400) • Pittsburgh, Pa. Thursday, Aug. 31 @ Carolina W, 17-14 (KDKA) PLAYING SURFACE: Natural Grass TV COVERAGE: CBS (locally KDKA-TV, channel 2) REGULAR SEASON (12-3) ANNOUNCERS: Sunday, Sept. 10 @ Cleveland W, 21-18 (CBS) Sunday, Sept. 17 MINNESOTA W, 26-9 (FOX) Spero Dedes (play-by-play) | Adam Archuleta (analyst) Sunday, Sept. 24 @ Chicago L, 23-17 OT (CBS) LOCAL RADIO: Steelers Radio Network Sunday, Oct. 1 @ Baltimore W, 26-9 (CBS) WDVE-FM (102.5)/WBGG-AM (970) Sunday, Oct. 8 JACKSONVILLE L, 30-9 (CBS) ANNOUNCERS: Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sunday, Oct. 15 @ Kansas City W, 19-13 (CBS) Tunch Ilkin (analyst) | Craig Wolfley (sideline) Sunday, Oct. 22 CINCINNATI W, 29-14 (CBS) NATIONAL RADIO: Westwood One Sunday, Oct. 29 @ Detroit W, 20-15 (NBC) Sunday, Nov. 5 BYE WEEK ANNOUNCERS: TBA Sunday, Nov. 12 @ Indianapolis W, 20-17 (CBS) Thursday, Nov. -

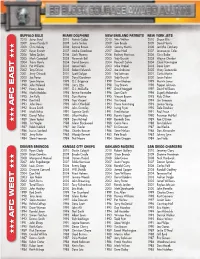

Afc East Afc West Afc East Afc

BUFFALO BILLS MIAMI DOLPHINS NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS NEW YORK JETS 2010 Jairus Byrd 2010 Patrick Cobbs 2010 Wes Welker 2010 Shaun Ellis 2009 James Hardy III 2009 Justin Smiley 2009 Tom Brady 2009 David Harris 2008 Chris Kelsay 2008 Ronnie Brown 2008 Sammy Morris 2008 Jerricho Cotchery 2007 Kevin Everett 2007 Andre Goodman 2007 Steve Neal 2007 Laveranues Coles 2006 Takeo Spikes 2006 Zach Thomas 2006 Rodney Harrison 2006 Chris Baker HHH 2005 Mark Campbell 2005 Yeremiah Bell 2005 Tedy Bruschi 2005 Wayne Chrebet 2004 Travis Henry 2004 David Bowens 2004 Rosevelt Colvin 2004 Chad Pennington 2003 Pat Williams 2003 Jamie Nails 2003 Mike Vrabel 2003 Dave Szott 2002 Tony Driver 2002 Robert Edwards 2002 Joe Andruzzi 2002 Vinny Testaverde 2001 Jerry Ostroski 2001 Scott Galyon 2001 Ted Johnson 2001 Curtis Martin 2000 Joe Panos 2000 Daryl Gardener 2000 Tedy Bruschi 2000 Jason Fabini 1999 Sean Moran 1999 O.J. Brigance 1999 Drew Bledsoe 1999 Marvin Jones 1998 John Holecek 1998 Larry Izzo 1998 Troy Brown 1998 Pepper Johnson 1997 Henry Jones 1997 O.J. McDuffie 1997 David Meggett 1997 David Williams 1996 Mark Maddox 1996 Bernie Parmalee 1996 Sam Gash 1996 Siupeli Malamala 1995 Jim Kelly 1995 Dan Marino 1995 Vincent Brown 1995 Kyle Clifton 1994 Kent Hull 1994 Troy Vincent 1994 Tim Goad 1994 Jim Sweeney AFC EAST 1993 John Davis 1993 John Offerdahl 1993 Bruce Armstrong 1993 Lonnie Young 1992 Bruce Smith 1992 John Grimsley 1992 Irving Fryar 1992 Dale Dawkins 1991 Mark Kelso 1991 Sammie Smith 1991 Fred Marion 1991 Paul Frase 1990 Darryl Talley 1990 Liffort Hobley -

We're from the Town with the Great Football Team

WE‟RE FROM THE TOWN WITH THE GREAT FOOTBALL TEAM: A PITTSBURGH STEELERS MANIFESTO By David Villiotti June 2009 1 To… Idie, Anthony & “Mrs. Swiss” ...tolerating my mania Tony …infecting me with Steelers Fever Mom …see Line 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE Preface 4 January, 2008 7 Behind Enemy Lines 8 Family of Origin…Swissvale 13 The Early Years: Pitt Stadium Days 18 Forbes Field Memories 28 Other Burgh Sports 34 Tony 38 Rest of The Boys 43 1970s: Unparallelled 46 Why Roy Gerela 64 1980s: Dark Decade 68 Why Mrs. Swiss Hates the Steelers 79 Stuff I Hate about the NFL 83 „90s: Changing of the Guard 87 Heckling 105 Family Gatherings 108 Taping 111 Rooting for Injuries 115 13 Minutes Ain‟t Enuff 120 Y2K Decade: First Five Years…Still Waiting 124 One For The Thumb 133 Cowher Out…Tomlin In 140 Steelers Trivia Challenge 145 Steelers Sites: Mill, Fury, Spiker, et al 149 Six!!! 156 City of Champions 209 Closing 214 *From “The Steelers Polka” by Jimmy Psihoulis 3 PREFACE Having catalogued my life by the ups and downs of the Pittsburgh Steelers Football Club, and having surpassed the half century mark in age, I endeavored to author a memoir of my life as a fan. This perhaps would be suited for a time capsule for my children, or alternatively as a project for a publisher whose business was really, really slow. For the past few years, I‟ve written a number of articles, under the screen name, Swissvale72 for a few Pittsburgh Steelers related websites, most notably, and of longest duration, was an association with Stillers.com, prior to my falling into disfavor with management. -

Pittsburgh Steelers (11-2) New England

PITTSBURGH STEELERS COMMUNICATIONS Burt Lauten - Director of Communications Dominick Rinelli - Public Relations/Media Manager PITTSBURGH STEELERS Angela Tegnelia - Public Relations Assistant 3400 South Water Street • Pittsburgh, PA 15203 412-432-7820 • Fax: 412-432-7878 www.steelers.com PITTSBURGH STEELERS (11-2) vs. NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS (10-3) Sunday, Dec. 17, 2017 • 4:25 p.m. (ET) • Heinz Field • Pittsburgh, Pa. REGULAR SEASON GAME #14 PITTSBURGH STEELERS 2017 SCHEDULE Pittsburgh Steelers (11-2) vs. PRESEASON (3-1) New England Patriots (10-3) Friday, Aug. 11 @ New York Giants W, 20-12 (KDKA) Sunday, Aug. 20 ATLANTA W, 17-13 (KDKA) DATE: Sunday, Dec. 17, 2017 | KICKOFF: 4:25 p.m. ET Saturday, Aug. 26 INDIANAPOLIS L, 19-15 (KDKA) SITE: Heinz Field (68,400) • Pittsburgh, Pa. Thursday, Aug. 31 @ Carolina W, 17-14 (KDKA) PLAYING SURFACE: Natural Grass TV COVERAGE: CBS (locally KDKA-TV, channel 2) REGULAR SEASON (11-2) ANNOUNCERS: Jim Nantz (play-by-play) Sunday, Sept. 10 @ Cleveland W, 21-18 (CBS) Tony Romo (analyst) | Tracy Wolfson (sideline) Sunday, Sept. 17 MINNESOTA W, 26-9 (FOX) Sunday, Sept. 24 @ Chicago L, 23-17 OT (CBS) LOCAL RADIO: Steelers Radio Network Sunday, Oct. 1 @ Baltimore W, 26-9 (CBS) WDVE-FM (102.5)/WBGG-AM (970) Sunday, Oct. 8 JACKSONVILLE L, 30-9 (CBS) ANNOUNCERS: Bill Hillgrove (play-by-play) Sunday, Oct. 15 @ Kansas City W, 19-13 (CBS) Tunch Ilkin (analyst) | Craig Wolfley (sideline) Sunday, Oct. 22 CINCINNATI W, 29-14 (CBS) NATIONAL RADIO: ESPN Radio Sunday, Oct. 29 @ Detroit W, 20-15 (NBC) ANNOUNCERS: Sunday, Nov. 5 BYE WEEK Sunday, Nov. -

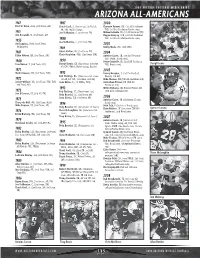

UA Football Pdf.Indd

2009 ARIZONA FOOTBALL MEDIA GUIDE ARIZONA ALL-AMERICANS 1947 1987 2000 Fred W. Enke, Back, (3rd Team, AP) Chuck Cecil, S, (Consensus,1st Kodak, Clarence Farmer, RB, (1st All Freshman FN, UPI, Walter Camp) TSN, 1st True Freshman Rivals.com) 1951 Joe Toffl emire, C, (2nd team FN) Michael Jolivette, CB, (1st All Freshman TSN) Jim Donarski, G, (2nd Team, AP) Reggie Sampay, C/G, (3rd All Freshman 1988 TSN, 1st True Freshman Rivals.com) 1955 Joe Toffl emire, C, (1st team FN) Art Luppino, Back, (2nd Team, 2002 Williamson) 1989 Bobby Wade, WR, (2nd TSN) 1961 Glenn Parker, OL, (2nd team FN) 2004 Chris Singleton, OLB, (2nd team TSN) Eddie Wilson, QB, (3rd Team, AP) Antoine Cason, CB, (1st All Freshman TSN, FWAA, Rivals.com) 1968 1990 Peter Graniello, OL, (2nd All Freshman Tom Nelson, T, (3rd Team, AP) Darryll Lewis, CB, (Consensus 1st team TSN, Rivals.com) Darryll Lewis AP, UPI, FWAA, Walter Camp, Kodak) 1971 2005 Mark Arneson, LB, (1st Team, TSN) 1992 Danny Baugher, P, (1st Pro Football Rob Waldrop, NG, (Consensus 1st team; Weekly, 3rd AP) 1972 1st AP, 1st UPI, 1st FWAA, 2nd FN) Mike Thomas, WR (TSN All-Freshman 2nd) Jackie Wallace, DB, (1st Team, UPI/ TSN; Josh Miller, P, (1st FWAA, TSN) Johnathan Turner, DE (TSN All- 3rd Team, AP) Freshman 3rd) 1993 Willie Tuitama, QB; Ronnie Palmer, LB 1973 Rob Waldrop, DT, (Unanimous 1st) (TSN All-Freshman HM) Jim O’Connor, OT, (3rd AP/FN) Tedy Bruschi, DE, (2nd team AP) Sean Harris, ILB, (3rd team AP) 2006 1975 Antoine Cason, CB (2nd team SI.com/ Theopolis Bell, WR, (1st Team, NEA) 1994 Rivals.com) Mike Dawson, -

Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame

Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame 6th Induction Ceremony Friday November 25, 2016 Langley’s Restaurant at Great Neck Country Club Waterford, Connecticut Platinum Sponsor The Mortimer Family and The Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame would like to thank the Mortimer family and GNCC for their wonderful support of our efforts to honor those who have made special contributions to Waterford athletics. In addition to helping us with the induction ceremony, their support helped us reach a goal of a permanent location to honor the members of the Hall of Fame. A perpetual plaque is now displayed outside the Francis X. Sweeney Field House at Waterford High School to serve as a lasting memory of the inductees. 2016 Induction Ceremony - Program of Events 6:00 PM Social Hour 7:00 PM Welcome Jim Cavalieri, HOF Committee Chair 7:15 PM Hall of Fame Inductions/Honorees Aaron Curry Stephen Harper Bridgit (Lawrence) Buscetto Joe Miller Kris Morton Rick Murallo Chris Podeszwa Katie Schoepfer The Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame The Waterford Athletic Hall of Fame was founded in 2002 by The Cactus Jack Foundation to honor those who have made special contributions to Waterford athletics, as a player, coach, administrator or community volunteer. Class of 2002 Class of 2004 Howard Christensen Bill Gardner Sr. Richard Cipriani Arnold Holm Gerard Rousseau Jan Merrill Morin Francis X. Sweeney Gary Swanson Joan Van Ness Class of 2008 Class of 2010 Ron Bugbee Marlene (Morth) Wiggins Joe Carey Liz Mueller Karen Mullins Glenn Rupert Gene Sutera David Sousa Norman Tonucci Warren Swanson Class of 2014 Lee Elci Ed Evento Billy Gardner Jr. -

2009-12-New Orleans:Layout 1.Qxd

NEW ORLEANS SAINTS 2009 WEEKLY MEDIA INFORMATION GUIDE NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS VS. NEW ORLEANS SAINTS NOV. 30, 2009 @ LOUISIANA SUPERDOME GAME INFORMATION • ROSTERS • DEPTH CHART STATISTICS • MINIBIOS • CLIPS NEW ORLEANS SAINTS HOST NEW ENGLAND PATRIOTS IN MONDAY NIGHT MATCHUP Following a 38-7 victory in Tampa Bay, plete only 17-of-33 passes for 126 yards with one where efficiency on offense, defense and special touchdown, three interceptions, one lost fumble teams carried them to the finish, the New lost and a 33.1 passer rating. DE Will Smith con- Orleans Saints will seek to at least retain their tinued his dominant play in the month of one game lead atop the NFC standings under the November with five tackles and one sack, his shine of Monday Night Football when they host sixth quarterback takedown in four games. He the New England Patriots (7-3) on a nationally leads the club and is tied for second in the NFC televised contest. and fifth in the NFL with 8.5 sacks and three The Saints enter the matchup against forced fumbles. Rookie CB Malcolm Jenkins one of the NFL’s top juggernauts, who have col- recorded an interception in his first NFL start, lected four Super Bowl appearances and three while he was joined in the pick parade by S Chris championships over the past ten years, with a Reis and LB Jonathan Vilma. 10-0 record, riding their first ten game win streak Monday’s matchup will feature two of in franchise history. The Saints and the the NFL’s most prolific offenses over the past Indianapolis Colts are the only unbeaten NFL three seasons, as both the Saints and the teams remaining entering week 12. -

Vernon Zoners Hear Objections to Condo Policy by BARBARA RICHMOND the Amendments, As Proposed by the PRD Zone

2 0 - EVENING HERALD, Fri,, Jan. 18, 1980 Vernon Zoners Hear Objections to Condo Policy By BARBARA RICHMOND The amendments, as proposed by the PRD zone. He said his clients property area, Daniel Walker, said concern about this saying they chose part of the special permit process or HrralH Rrporirr Kunzli include provisions for con own a parcel of land in a PRD zone he could count on one hand the to live in an apartment and cannot af the permit need not be granted. dominium conversions of existing VERNON — There were many and want to build condominiums on number of people who want con ford to buy a condominium for ateut Kunzli said the condominium con You Can Be a Winner! objections, some stronger than apartments. it. Right now the zoning laws require dominiums in town. $40,000. version issue is much more complex Some lucky couple will win a trip to Florida and spend The Planning Commission at least five acres of land in the PRD He cited the fact that the Towns of A statement written by Kunzli and iiaurhpfitpr others, at a public hearing of the and difficult than that of new con four days and three nights at the Sonesta Beach Hotel in Zoning Commission Thursday night, recommended that the Zoning Com zones. The proposed laws would Manchester and Coventry are presented by John Loranger, plan struction. "The extensive hearing Key Biscayne. The Herald, in cooperation with the mission approve the amendment for change this to three acres. fighting HUD. He said also there on zone changes that would allow ning consultant, stressed the fact process as well as the commission's LaBonne Travel Agency and participating merchants, is new condominiums but said it wasn't Martin Luginbuhl, a local should be a different set of that there is a housing shortage ail rules of procedure permit adoption of condominium construction and con offering the Florida trip.