Appendix B 74

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democratic Audit on Lobbyist Code

The Lobbying Code of Conduct: An Appraisal JOHN WARHURST Democratic Audit Discussion Paper 4/08 April 2008 John Warhurst is Professor of Political Science, Faculty of Arts, Australian National University, and Adjunct Professor, School of Political and International Studies, Flinders University. He is author of Behind Closed Doors: Politics, Scandals and the Lobbying Industry (UNSW Press, 2007). Democratic Audit Discussion Papers ISSN 1835-6559 1 The Rudd government’s attempt to register lobbyists has taken a significant further step.1 The Cabinet Secretary, Senator John Faulkner, released an exposure draft of the proposed Lobbying Code of Conduct on 2 April.2 This development fulfilled an election promise, though it has emerged a little later than promised. This reflects both the complexity of the issue, the size of the task and the congestion the new government is facing as it deals with a multiplicity of issues and a crowded agenda. Before Christmas, in early December, the government had begun to tackle the problem and prefigured some of the themes in a new chapter on Standards of Ministerial Ethics for the Guide on Key Elements of Ministerial Responsibility, last issued in December 1998.3 The lobbying industry continues to grow in all jurisdictions, and there are hundreds of commercial lobbyists and thousands of pressure groups operating in Canberra and the state capitals. Lobbying regulation is an issue of considerable international concern. It is one of those issues that bother governments of all persuasions across the world, but dealing with it adequately is generally regarded as unfinished business.4 There has been a previous register of lobbyists in Australia, though for some unaccountable reason Senator Faulkner claims this latest version as the first formal lobbyists register ever adopted by a federal government. -

Lachlan Harris

175 Varick Street +(917) 446 0194 I Level6 [email protected] ' New York New York 10014 Lachlan Harris Employment 2010 - 2015: Co-Founder and CEO of One Big Switch History • Co-Founded and grew One Big Switch from inception into one of the world's largest discount energy broker with over 800,000 members in Australia, The United States of America, the UK & Ireland. • One Big Switch now runs collective switching campaigns, focused I mainly on energy and insurance products in 4 countries. • Since 2010, One Big Switch has served energy providers around the world as a broker and aggregator, delivering large volumes of annual switches due to One Big Switch's unique consumer network and editorial model. • Over 160,000 households have now switched energy suppliers as part of a One Big Switch campaign. • One Big Switch has offices in Sydney, London, Dublin and New York, and is a global leader on collective switching. • As Global CEO I have full responsibility for managing all elements of the global One Big Switch business. 2007-2010: Senior Press Secretary, Australian Prime Minister, The Hon Kevin Rudd MP Coordinate all media activities for the Australian Government including: • Management of the whole of Government media strategy for the full term of Prime Minister Kevin Rudd. • Design and implement a 24-hour a day, 7 day a week whole of Government I coordinated media monitoring and briefing system. • Coordinate the daily media activities of the Australian Government, including the media activities of the Prime Minister, all Cabinet Ministers, all Members of the Government, and all Government Department's. -

DPM Teo Calls on Australian Prime Minister

DPM Teo Calls on Australian Prime Minister 23 Nov 2010 Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Teo Chee Hean calling on Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard at the Australian Parliament House. Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Defence Teo Chee Hean called on Australian Prime Minister Julia Gillard in Canberra today. Both parties reaffirmed the close and broad-based bilateral relations between the two countries, of which the strong and long-standing defence ties are a key pillar. Their meeting also reinforced the political support from both countries for the extensive interactions and cooperation between both armed forces, including the ongoing cooperation in the multinational reconstruction efforts in Afghanistan. During his working visit to Australia, Mr Teo also met with Defence Minister Stephen Smith, Minister for Foreign Affairs Kevin Rudd, Senator John Faulkner, Opposition Leader Tony Abbott, Shadow Minister for Defence David Johnston, Special Minister of State for the Public Service and Integrity Gary Gray, Minister for Indigenous Employment and Economic Development, Minister for Sport, and Minister for Social Housing and Homelessness Honourable Mark Arbib and Chief Government Whip Joel Fitzgibbon. At a joint press conference with Mr Smith yesterday, Mr Teo reiterated Singapore's appreciation of the strong and extensive defence relationship between Singapore and Australia. "We are very grateful for the opportunities that Australia has provided for Singapore to train here in Australia. It 1 has been a great help to us, our training in Shoalwater Bay as well as our flight training in Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) Base Pearce in Perth. I have just visited both places and it is going very well, and we are very grateful for the cooperation," said Mr Teo. -

Inaugural Speech

INAUGURAL SPEECH The PRESIDENT: I remind honourable members that this is the member's first speech and she should be given all due consideration. Before the honourable member starts, I welcome into my gallery members of the Hon. Rose Jackson's family, including her husband, Sam Crosby, their children, Oscar and Charlotte, her father, Mr Martin Butler, her mother-in-law, Mrs Bronwyn Crosby, and her brother, Joe. I also welcome into the public gallery the Hon. Chris Bowen, member for McMahon in the Australian Parliament. I welcome you all in the House this evening for the member's first speech. The Hon. ROSE JACKSON (18:01): The land we are on is called Eora. The first people here were the Gadigal. In 1909 this Parliament passed the Aborigines Protection Act, which gave legal force to the Aborigines Welfare Board and its wide-ranging control over the lives of Aboriginal people. In doing so, it introduced one of the deepest sources of our national shame by codifying the board's power to remove Aboriginal children from their families. I acknowledge the Gadigal today in this place not as a mere hat tip or commonplace convention but in solemn acknowledgement that the laws that gave the New South Wales Government power to steal the children of Aboriginal families, to take the babies from their mummies, were laws that were made in this very room, in this Parliament House, by our predecessors. The lives and resilience of the Gadigal should serve to inspire and humble us. They should stand as a profound warning: What we do here matters. -

Second Minister for Defence Calls on Australian Defence Minister

Second Minister for Defence Calls on Australian Defence Minister 23 Nov 2009 Minister for Education and Second Minister for Defence Ng Eng Hen discussing regional security issues with Minister for Defence Senator John Faulkner at Parliament House, Canberra, Australia. Minister for Education and Second Minister for Defence Ng Eng Hen called on Australian Minister for Defence Senator John Faulkner in Canberra this morning. During their meeting, the two leaders discussed regional security issues of mutual concern, and reaffirmed the strong and broad-based bilateral defence relations between Singapore and Australia. Dr Ng, who is on an official visit to Australia from 22 to 25 November 2009, also called on Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Education Julia Gillard and Shadow Minister for Defence Senator David Johnston, and met with Minister for Defence Personnel, Material and Science Greg Combet. Tomorrow, Dr Ng will visit Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) troops participating in the annual Exercise Wallaby at the Shoalwater Bay Training Area (SWBTA) in Queensland, Australia. He will observe an integrated livefiring exercise involving major air and land platforms such as the Apache attack helicopters, Pegasus lightweight howitzers and Leopard 2A4 Main 1 Battle Tanks. Some 3,900 SAF personnel are taking part in this year's exercise, which is being conducted from 16 October to 29 November 2009. Dr Ng's visit to Australia is part of the regular ministerial exchanges between Singapore and Australia and underscores the close bilateral defence ties between the two countries. The SAF and the Australian Defence Force also interact extensively through bilateral and multilateral training exercises, visits, professional exchanges and military courses. -

The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010

The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010 The Rudd Government Australian Commonwealth Administration 2007–2010 Edited by Chris Aulich and Mark Evans Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at: http://epress.anu.edu.au/rudd_citation.html National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: The Rudd government : Australian Commonwealth administration 2007 - 2010 / edited by Chris Aulich and Mark Evans. ISBN: 9781921862069 (pbk.) 9781921862076 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: Rudd, Kevin, 1957---Political and social views. Australian Labor Party. Public administration--Australia. Australia--Politics and government--2001- Other Authors/Contributors: Aulich, Chris, 1947- Evans, Mark Dr. Dewey Number: 324.29407 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design by ANU E Press Illustrations by David Pope, The Canberra Times Printed by Griffin Press Funding for this monograph series has been provided by the Australia and New Zealand School of Government Research Program. This edition © 2010 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgments . vii Contributors . ix Part I. Introduction 1 . It was the best of times; it was the worst of times . 3 Chris Aulich 2 . Issues and agendas for the term . 17 John Wanna Part II. The Institutions of Government 3 . The Australian Public Service: new agendas and reform . 35 John Halligan 4 . Continuity and change in the outer public sector . -

ANZSOG Case Program Revealing the ‘Real Julia’: Authenticity and Gender in Australian Political Leadership (A) 2016-185.1

ANZSOG Case Program Revealing the ‘Real Julia’: authenticity and gender in Australian political leadership (A) 2016-185.1 Julia Gillard became Australia’s 27th prime minister and the first woman to have the role when, as his deputy, she ousted Kevin Rudd in a sudden leadership coup in 2010. The challenge was prompted by widespread concern within the ruling Labor Party at Rudd’s domineering leadership style, including tight control of access to information and inability to reach timely decisions. Gillard, by contrast, was known for her ability to negotiate, plan and get things done. She sought to position herself as an authentic leader, ‘the real Julia,’ openly sharing information, standing by her personal values and choices and, as she says in her autobiography My Story, acknowledging mistakes as opportunities to learn. In the 2010 election campaign she pledged that: As prime minister, I will be driven by the values I have believed in all my life. The importance of hard work, the fulfilling of the obligation that you owe to yourself and to others to earn your keep and do your best.(...) In my life I have made my own choices about how I want to live. I do not seek anyone’s endorsement of my choices; they are mine and mine alone. I do not believe that as prime minister it is my job to preach on personal choices. However, it is my job to urge we respect each other’s personal choices.1 A better chance in life Julia Eileen Gillard was born in Wales, and her family migrated to Adelaide, Australia in 1966 when Gillard was four years old to give the young girl who had suffered severe recurring chest problems a better chance in life. -

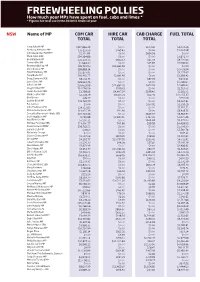

Freewheeling Pollies How Much Your Mps Have Spent on Fuel, Cabs and Limos * * Figures for Total Use in the 2010/11 Financial Year

FREEWHEELING POLLIES How much your MPs have spent on fuel, cabs and limos * * Figures for total use in the 2010/11 financial year NSW Name of MP COM CAR HIRE CAR CAB CHARGE FUEL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL TOTAL Tony Abbott MP $217,866.39 $0.00 $103.42 $4,559.36 Anthony Albanese MP $35,123.59 $265.43 $0.00 $1,394.98 John Alexander OAM MP $2,110.84 $0.00 $694.56 $0.00 Mark Arbib SEN $34,164.86 $0.00 $0.00 $2,806.77 Bob Baldwin MP $23,132.73 $942.53 $65.59 $9,731.63 Sharon Bird MP $1,964.30 $0.00 $25.83 $3,596.90 Bronwyn Bishop MP $26,723.90 $33,665.56 $0.00 $0.00 Chris Bowen MP $38,883.14 $0.00 $0.00 $2,059.94 David Bradbury MP $15,877.95 $0.00 $0.00 $4,275.67 Tony Burke MP $40,360.77 $2,691.97 $0.00 $2,358.42 Doug Cameron SEN $8,014.75 $0.00 $87.29 $404.41 Jason Clare MP $28,324.76 $0.00 $0.00 $1,298.60 John Cobb MP $26,629.98 $11,887.29 $674.93 $4,682.20 Greg Combet MP $14,596.56 $749.41 $0.00 $1,519.02 Helen Coonan SEN $1,798.96 $4,407.54 $199.40 $1,182.71 Mark Coulton MP $2,358.79 $8,175.71 $62.06 $12,255.37 Bob Debus $49.77 $0.00 $0.00 $550.09 Justine Elliot MP $21,762.79 $0.00 $0.00 $4,207.81 Pat Farmer $0.00 $0.00 $177.91 $1,258.29 John Faulkner SEN $14,717.83 $0.00 $0.00 $2,350.51 Mr Laurie Ferguson MP $14,055.39 $90.91 $0.00 $3,419.75 Concetta Fierravanti-Wells SEN $20,722.46 $0.00 $649.97 $3,912.97 Joel Fitzgibbon MP 9,792.88 $7,847.45 $367.41 $2,675.46 Paul Fletcher MP $7,590.31 $0.00 $464.68 $2,475.50 Michael Forshaw SEN $13,490.77 $95.86 $98.99 $4,428.99 Peter Garrett AM MP $39,762.55 $0.00 $0.00 $1,009.30 Joanna Gash MP $78.60 $0.00 -

Australia – East Asia/US Relations

Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations Australia-East Asia/US Relations: Election plus Marines, Joint Facilities and the Asian Century Graeme Dobell Australian Strategic Policy Institute The 12 months under review saw the unfolding of the withdrawal timetable from Afghanistan, the second rotation of US Marines to northern Australia, the first “Full Knowledge and Concurrence” statement on US facilities on Australian soil in six years, and the end of Australia’s long-term military deployments in Timor Leste and Solomon Islands. The Gillard government produced a trio of major policy statements built on an understanding that Asia’s “extraordinary ascent” means Australia is entering “a truly transformative period in our history.” In the words of the Australia in the Asian Century White Paper: “In managing the intersections of Australia’s ties with the United States and China, we will need a clear sense of our national interests, a strong voice in both relationships and effective diplomacy.” Meanwhile, Australian politics experienced a bit of turmoil. The Labor government discarded Australia’s first female prime minister in an attempt to appease the voters, but instead the voters discarded the Labor government. So it was that in the national election on Sept. 7, Australia got its third prime minister in the same calendar year. After six years of Labor rule, the Liberal- National Coalition led by Tony Abbott is back in power. Plummeting opinion polls had caused the Labor Parliamentary Caucus to vote out Julia Gillard as leader in June and elect Kevin Rudd as prime minister. Thus, Labor returned to the man it had thrown out of the prime ministership in 2010, afraid he could not win the looming 2010 election. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

ADDENDA All dates are 1994 unless stated otherwise EUROPEAN UNION. Entry conditions for Austria, Finland and Sweden were agreed on 1 March, making possible these countries' admission on 1 Jan. 1995. ALGERIA. Mokdad Sifi became Prime Minister on 11 April. ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA. At the elections of 8 March the Antigua Labour Party (ALP) gained 11 seats. Lester Bird (ALP) became Prime Minister. AUSTRALIA. Following a reshuffle in March, the Cabinet comprised: Prime Minis- ter, Paul Keating; Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Housing and Regional Development, Brian Howe; Minister for Foreign Affairs and Leader of the Govern- ment in the Senate, Gareth Evans; Trade, Bob McMullan; Defence, Robert Ray; Treasurer, Ralph Willis; Finance and Leader of the House, Kim Beazley; Industry, Science and Technology, Peter Cook; Immigration and Ethnic Affairs, Nick Bolkus; Employment, Education and Training, Simon Crean; Primary Industries and Energy, Bob Collins; Social Security, Peter Baldwin; Industrial Relations and Transport, Laurie Brereton; Attorney-General, Michael Lavarch; Communications and the Arts and Tourism, Michael Lee; Environment, Sport and Territories, John Faulkner; Human Services and Health, Carmen Lawrence. The Outer Ministry comprised: Minister for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs, Robert Tickner; Special Minister of State (Vice-President of the Executive Council), Gary Johns; Develop- ment Co-operation and Pacific Island Affairs, Gordon Bilney; Veterans' Affairs, Con Sciacca; Defence Science and Personnel, Gary Punch; Assistant Treasurer, George Gear; Administrative Services, Frank Walker; Small Businesses, Customs and Construction, Chris Schacht; Schools, Vocational Education and Training, Ross Free; Resources, David Beddall; Consumer Affairs, Jeannette McHugh; Justice, Duncan Kerr; Family Services, Rosemary Crowley. -

4 December 2011

As at 24/11/11 46th National Conference 2 – 4 December 2011 Delegates and Proxies President and Vice Presidents To be advised Federal Parliamentary Leaders Delegates Proxy Delegates Julia Gillard Wayne Swan Chris Evans Stephen Conroy Federal Parliamentary Labor Party Representatives Delegates Doug Cameron David Feeney Gavin Marshall Anne McEwen Amanda Rishworth Matt Thistlethwaite Australian Young Labor Delegates Sarah Cole David Latham Mem Suleyman Australian Capital Territory Delegates & Proxies Katy Gallagher – Chief Minister Delegates Proxy Delegates Andrew Barr Meegan Fitzharris Dean Hall Amy Haddad Luke O'Connor Klaus Pinkas Alicia Payne Kristin van Barneveld Athol Williams Elias Hallaj, Non-voting Territory Secretary New South Wales Delegates and Proxies John Robertson - Leader of the Opposition Linda Burney – Leader’s Proxy Delegates Proxy Delegates Anthony Albanese Ed Husic Rob Allen Gerry Ambroisine Veronica Husted George Barcha Kirsten Andrews Rose Jackson Susai Benjamin Mark Arbib Johno Johnson Danielle Bevins-Sundvall Louise Arnfield Michael Kaine Alex Bukarica Timothy Ayres Graeme Kelly Meredith Burgmann Stephen Bali Grahame Kelly Michael Butterworth Paul Bastian Janice Kershaw Tony Catanzariti Derrick Belan Judith Knight Brendan Cavanagh Sharon Bird Michael Lee Jaime Clements Stephen Birney Mark Lennon Jeff Condron David Bliss Sue Lines Sarah Conway Phillip Boulten Rita Mallia Anthony D’Adam Christopher Bowen Maurice May Michael Daley Mark Boyd Jennifer McAllister Jo-Ann Davidson Corrine Boyle Robert McClelland Felix Eldridge -

A Love Affair with Latham? AUSTRALIAN NEWS MEDIA CHRONICLE JANUARY-JUNE 2004

A Love Affair with Latham? AUSTRALIAN NEWS MEDIA CHRONICLE JANUARY-JUNE 2004 John Harrison “Wishful intelligence, the desire to please or reassure the recipient, was the most dangerous commodity in the whole realm of secret information.” James Bond in Ian Fleming’s Thunderball (1961:112) This critical interpretation of key issues and events in the Australian news media in the first half of 2004 analyses trends in four areas: the reporting of politics, changes in media policy and regulation, attempts to limit media freedom through restrictions on reporting, and movements in people, ownership, and broadcasting ratings. Of particular significance are the failure of the Australian Broadcasting Authority to adequately address cash for comment, a failure which had a considerable flow on effect; continuing challenges to the integrity of the ABC from within and without; mooted changes in defamation law; and a perception, again from within and without, that the Nine television network was losing its pre-eminence in commercial broadcasting. Much of the reporting and the policy debate were conditioned by the prospect of a closely contested federal election in the second half of the year. POLITICS: Luvin’ Latham The Australian media’s love affair with Opposition Leader Mark Latham is the big political news story of the period under review. Pictures of Mark Latham reading to small children; and then Latham standing beside Bob Brown in the Tasmanian forests, Mark Latham putting out the garbage at his western Sydney home, Mark Latham’s man boobs, and Mark and his son Ollie sharing a chip butty. The pic-facs have been endless.1 Elected on 2 December 2003 as a replacement for the hapless Simon Crean by the narrowest of margins (47 to 45), Latham’s ascent was a surprise for many journalists and apparently the Liberal 1 (Photo: Sydney Daily Telegraph 24 April 2004).