Corpus Planning for Scottish Gaelic? Collaborative Development of Basic Grammatical Norms for Twenty-First-Century Speakers

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Acronym Title Brief Description

Education Acronyms and Their Meanings Acronym Title Brief Description AB 430 Assembly Bill 430 Training for administrators in state adopted English language arts/math curriculum ADA Average Daily Attendance This number is determined by dividing the total number of days of student attendance by the number of total days in the district’s school year. If a student attended school every school day during the year, he/she would generate 1.0 ADA. This number is used to fund many programs. AMAO Annual Measurable Achievement Objectives A performance objective, or target, that the district receiving Title III funds must meet each year for its English learners. AMO Annual Measurable Objectives A school must demonstrate a minimum percentage of its students scoring proficient or above on a standards-based assessment in English language arts and math. API Academic Performance Index State – An annual achievement score given by the state to schools and districts. The state’s target is all schools reach 875 by 2014. APS Academic Program Survey The Academic Program Survey (APS) of nine essential program components for instructional success is the foundational tool at the school level. The APS measures structures for creating a coherent instructional program and recent revisions explicitly address the needs of SWDs and English Learners (ELs). AYP Adequate Yearly Progress Federal – Growth targets the federal government set for student achievement. The federal target is 100% proficiency by 2014. BTSA Beginning Teacher Support and Assessment An initiative to provide individualized support based on assessment information for beginning teachers. CAHSEE California High School Exit Exam All public school students are required to pass the exam to earn a high school diploma. -

An Approach to Patronymic Names As a Resource for Familiness

European Journal of Family Business (2016) 6, 32---45 EUROPEAN JOURNAL OF FAMILY BUSINESS www.elsevier.es/ejfb ORIGINAL ARTICLE An approach to patronymic names as a resource for familiness and as a variable for family business identification a,∗ b c Fernando Olivares-Delgado , Alberto Pinillos-Laffón , María Teresa Benlloch-Osuna a Chair of Family Business, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain b Department of Communication and Social Psychology, University of Alicante, Alicante, Spain c Department of Communication Sciences, University Jaume I, Castellón, Spain Received 20 April 2016; accepted 13 June 2016 Available online 18 July 2016 JEL CODES Abstract This paper aims to hint at a theory of family business naming. Besides, it puts forward E22; two kinds of practical proposals. The former intends to integrate the patronymic name as M30; an intangible resource for corporate brand management, in addition to family branding and M14; familiness. The latter proposals aim at including the patronymic company name in Spanish as M19 a variable in research methods on family business identification. © 2016 European Journal of Family Business. Published by Elsevier Espana,˜ S.L.U. This is an KEYWORDS open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- Corporate naming; nc-nd/4.0/). Brand name; Patronymic trade mark; Family name firm; Family brand; Company name CÓDIGOS JEL Una aproximación al nombre patronímico como recurso de familiness y como E22; variable para la identificación de la empresa familiar M30; M14; Resumen Nuestro trabajo realiza apuntes para una teoría del nombre de la empresa familiar. M19 Además, este trabajo formula 2 tipos de proposiciones prácticas. -

Title / Project Acronym

NAME of PI PROJECT TYPE PROJECT ACRONYM LINZ INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY JOHANNES KEPLER UNIVERSITY RESEARCH PROPOSAL TITLE / PROJECT ACRONYM Principal Name Investigator Email Co-Principal Names Investigators Emails Project Type Young Career, Seed, Advance, Co Funding, or Career Accelerator Project Duration # months Funding € Requested Hosting Name of Institute or Department Institute or Name of Person Department Email Industrial Company Collaborator(s) Name of Person Email Co-Funding Provided (if any): € Scientific e.g., Physics Field(s) Scientific https://www.fwf.ac.at/fileadmin/files/Dokumente/Antragstellung/wiss-disz- Discipline(s) 201507.pdf (FWF categories) Primary Goals Additional Infrastructure you require access to Infrastructure Needed Abstract 1/6 NAME of PI PROJECT TYPE PROJECT ACRONYM A. Proposal (Free Form) Young Career Projects, Seed Projects, and Career Accelerator Projects require a max. 10 page proposal. Project description: 1. Scientific/scholarly aspects What is High Risk / What is High Gain? Aims (hypotheses or research questions): Relevance to international research in the field (international status of the research); Explanation of how the project could break new ground in research (innovative aspects); Importance of the expected results for the discipline (based on the project described); Methods; Work plan, project schedule and strategies for dissemination of results; Cooperation arrangements (national and international); Where ethical issues have to be considered in the proposed research project: All potential ethical, security-related or regulatory aspects of the proposed research project and the planned handling of those issues must be discussed in a separate paragraph. In particular, the benefits and burdens arising from the experiments as well as their effects on the test subjects/objects should be explained in detail. -

Fedramp Master Acronym and Glossary Document

FedRAMP Master Acronym and Glossary Version 1.6 07/23/2020 i[email protected] fedramp.gov Master Acronyms and Glossary DOCUMENT REVISION HISTORY Date Version Page(s) Description Author 09/10/2015 1.0 All Initial issue FedRAMP PMO 04/06/2016 1.1 All Addressed minor corrections FedRAMP PMO throughout document 08/30/2016 1.2 All Added Glossary and additional FedRAMP PMO acronyms from all FedRAMP templates and documents 04/06/2017 1.2 Cover Updated FedRAMP logo FedRAMP PMO 11/10/2017 1.3 All Addressed minor corrections FedRAMP PMO throughout document 11/20/2017 1.4 All Updated to latest FedRAMP FedRAMP PMO template format 07/01/2019 1.5 All Updated Glossary and Acronyms FedRAMP PMO list to reflect current FedRAMP template and document terminology 07/01/2020 1.6 All Updated to align with terminology FedRAMP PMO found in current FedRAMP templates and documents fedramp.gov page 1 Master Acronyms and Glossary TABLE OF CONTENTS About This Document 1 Who Should Use This Document 1 How To Contact Us 1 Acronyms 1 Glossary 15 fedramp.gov page 2 Master Acronyms and Glossary About This Document This document provides a list of acronyms used in FedRAMP documents and templates, as well as a glossary. There is nothing to fill out in this document. Who Should Use This Document This document is intended to be used by individuals who use FedRAMP documents and templates. How To Contact Us Questions about FedRAMP, or this document, should be directed to [email protected]. For more information about FedRAMP, visit the website at https://www.fedramp.gov. -

English Style Guide: a Handbook for Translators, Revisers and Authors of Government Texts

clear writing #SOCIAL MEDIA ‘Punctuation!’ TRANSLATING Useful links English Style Guide A Handbook for Translators, Revisers and Authors of Government Texts Second edition ABBREVIATIONSediting June 2019 Publications of the Prime Minister’s Oce 2019 :14, Finland The most valuable of all talents is that Let’s eat, Dad! of never using two words when one will do. Let’s eat Dad! Thomas Jefferson Translation is not a matter of words only: it is A translation that is clumsy or a matter of making intelligible a whole culture. stilted will scream its presence. Anthony Burgess Anonymous One should aim not at being possible to understand, Without translation I would be limited but at being impossible to misunderstand. to the borders of my own country. Quintilian Italo Calvino The letter [text] I have written today is longer than Writing is thinking. To write well is usual because I lacked the time to make it shorter. to think clearly. That's why it's so hard. Blaise Pascal David McCullough 2 Publications of the Prime Minister’s Office 2019:14 English Style Guide A Handbook for Translators, Revisers and Authors of Government Texts Second edition June 2019 Prime Minister’s Office, Helsinki, Finland 2019 2 Prime Minister’s Office ISBN: 978-952-287-671-3 Layout: Prime Minister’s Office, Government Administration Department, Publications Helsinki 2019 ISTÖM ÄR ER P K M K Y I M I KT LJÖMÄR Painotuotteet Painotuotteet1234 5678 4041-0619 4 Description sheet Published by Prime Minister’s Office, Finland 28 June 2019 Authors Foreign Languages Unit, Translation -

ENIAC-ED-90 Template for Part B Acronym and Proposal Title

Part B Proposal Acronym Project Logo (if available) ENIAC-ED-90 Template for Part B to be used in preparing the Technical Annex in the PO phase and the FPP Phase of proposals for Call 2012-2 Version 1.0 Acronym and Proposal Title IMPORTANT REMARKS (Delete this text in final version) The use of this template is MANDATORY in the PO and FPP Phase. Tables are introduced in a separate MANDATORY Excel spread sheet using the template. Using the templates (document and tables) will save you work later on as the same template will be used during negotiations and as Annex 1 in the JU Grant Agreement How to use this template: The text in italics is meant as guide and should be deleted in the final copy. The text is meant to be filled in with the appropriate information. Quality is preferred over quantity. All sections must be filled in. The maximum page indication for the PO phase corresponds approximately to the typical number of pages for a large project. As only PDFs are up loadable the final MS Word document must be transformed in a Pdf document. Part B Proposal Acronym 1 ESSENTIALS ....................................................................................................................... 3 2 PUBLISHABLE PROJECT SUMMARY ............................................................................... 5 3 RELEVANCE AND CONTRIBUTIONS TO CONTENT AND CALL OBJECTIVES ............ 6 4 R&D INNOVATION AND TECHNICAL EXCELLENCE....................................................... 7 5 SCIENTIFIC & TECHNICAL APPROACH AND WORK PLAN .......................................... -

Practitioner Acronym Table

Practitioner Acronym Table AAP American Academy of Pediatrics ABAI American Board of Allergy and Immunology ABFP American Board of Family Practitioners ABO American Board of Otolaryngology ABPN American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology AK Acupuncturist (Pennsylvania) AOBFP American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians American Osteopathic Board of Special Proficiency in Osteopathic Manipulative AOBSPOMM Medicine AP Acupuncture Physician ASG Affiliated Study Group BHMS Bachelor of Homeopathic Medicine and Surgery BSN Bachelor of Science, Nursing BVScAH Bachelor of Veterinary Science and Animal Husbandry CA Certified Acupuncturist CAAPM Clinical Associate of the American Academy of Pain Management CAC Certified Animal Chiropractor CCH Certified in Classical Homeopathy CCSP Certified Chiropractic Sports Physician CRNP Certified Registered Nurse Practitioner CRRN Certified Rehabilitation Registered Nurse CSPOMM Certified Specialty of Proficiency in Osteopathic Manipulation Medicine CVA Certified Veterinary Acupuncturist DAAPM Diplomate of American Academy of Pain Management DABFP Diplomate of the American Board of Family Practice DABIM Diplomate of the American Board of Internal Medicine DAc Diplomate in Acupuncture DAc (RI) Doctor of Acupuncture, Rhode Island DAc (WV) Doctor of Acupuncture, West Virginia DACBN Diplomate of American Chiropractic Board of Nutrition DACVD Diplomate of the American College of Veterinary Dermatology DC Doctor of Chiropractic DDS Doctor of Dentistry DHANP Diplomate of the Homeopathic Academy of Naturopathic -

Author's Note on Transcriptions

AUTHOR’S NOTE ON TRANSCRIPTIONS, TRANSLATIONS, ARCHIVES, AND SPANISH NAMING PRACTICES Although I have not included the Spanish originals of most colonial documents discussed in this volume, I include some brief transcrip- tions in the endnotes or parenthetically. My transcriptions attempt to preserve the orthography and punctuation of the original documents while at the same time rendering them comprehensible to twenty- first- century readers. Thus, I spell out most abbreviations and generally convert the letter “f” to “s” and the initial “rr” to “r,” but do not always convert “y” to “i,” “u” to “v,” or add the letter “h” where it is missing. I do not include accent marks in my transcriptions, as they were not used in the colonial period; for this reason, names like “Bogotá” will appear with an accent mark in the text, but without an accent in doc- umentary citations and quotations. I do not reconcile divergent spell- ings of a word or a proper name, which might be written in different ways in the same document; this is particularly true for toponyms and anthroponyms in native languages, which Spanish scribes struggled to record using Castillian phonological conventions, although they were not proficient in the language in question. I also preserve the gender of certain nouns, such as “la color,” in their early modern form. Co- lonial documentary writing frequently has run- on sentences. In the interests of making quotations in translation more readable, I have opted for dividing some run- on sentences into more coherent phrases in my translations. Likewise, I have removed “said” (dicho/a), which means “aforementioned,” from certain translations in the interests of a more fluid reading, although I have retained it where it is central to the meaning of the sentence. -

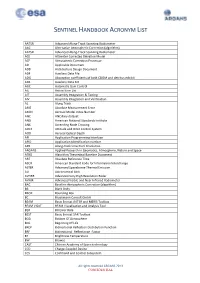

Sentinel Handbook Acronym List

SENTINEL HANDBOOK ACRONYM LIST AATSR AdvAnced Along-TrACk Scanning Radiometer AAC Alternative AtmospheriC CorreCtion (Algorithm) AATSR AdvAnced Along-TrACk Scanning Radiometer ACE Altimeter CorreCted ElevAtion Model ACP AtmospheriC CorreCtion Processor AD AppliCAble Document ADD ArChiteCture Design Document ADF AuxiliAry DAtA File ADG Absorption CoeffiCients of both CDOM And detritus exhibit ADS AuxiliAry DAtA Set AGC AutomAtiC GAin Control AIL Action Item List AIT Assembly IntegrAtion & Testing AIV Assembly IntegrAtion And VerifiCAtion AL Along TrACk AME Absolute MeAsurement Error AMIN Aerosol Model Index Number ANC ANCillary dAtAset ANSI AmeriCAn NAtional Standards Institute ANX AsCending Node Crossing AOCS Attitude And Orbit Control System AOD Aerosol OptiCAl Depth API AppliCAtion ProgrAmming InterfACe APID AppliCAtion IdentifiCAtion number APR Along-traCk view Pixel Resolution ARGANS Applied ReseArCh in GeomAtiCs, Atmosphere, NAture And SpaCe ATBD Algorithm TheoretiCAl Baseline Document ART Absolute Reference Time ASCII AmeriCAn StAndard Code for InformAtion InterChange ASTER AdvAnced SpaCeborne ThermAl Emission AU AstronomiCAl Unit AVHRR AdvAnced Very High Resolution Radar AVNIR AdvAnced Visible And NeAr InfrAred Radiometer BAC Baseline AtmospheriC CorreCtion (Algorithm) BB BlACk Body BBOX Bounding Box BC BrockmAnn Consult GmbH BEAM BasiC EnvisAt AATSR And MERIS Toolbox BEAM VISAT BEAM VisualisAtion And Analysis Tool BER Bit Error Rate BEST BasiC EnvisAt SAR Toolbox BOA Bottom Of Atmosphere BOL Beginning Of Life BRDF BidireCtional -

Nudges for Privacy and Security: Understanding and Assisting Users' Choices Online 44

Nudges for Privacy and Security: Understanding and Assisting Users’ Choices Online ALESSANDRO ACQUISTI, Carnegie Mellon University IDRIS ADJERID, University of Notre Dame REBECCA BALEBAKO, Carnegie Mellon University LAURA BRANDIMARTE, University of Arizona LORRIE FAITH CRANOR, Carnegie Mellon University SARANGA KOMANDURI, Civis Analytics PEDRO GIOVANNI LEON, Banco de Mexico 44 NORMAN SADEH, Carnegie Mellon University FLORIAN SCHAUB, University of Michigan MANYA SLEEPER, Carnegie Mellon University YANG WANG, Syracuse University SHOMIR WILSON, University of Cincinnati Advancements in information technology often task users with complex and consequential privacy and security decisions. A growing body of research has investigated individuals’ choices in the presence of privacy and information security tradeoffs, the decision-making hurdles affecting those choices, and ways to mitigate such hurdles. This article provides a multi-disciplinary assessment of the literature pertaining to privacy and security decision making. It focuses on research on assisting individuals’ privacy and security choices with soft paternalistic interventions that nudge users toward more beneficial choices. The article discusses potential benefits of those interventions, highlights their shortcomings, and identifies key ethical, design, and research challenges.• • CCS Concepts: Security and privacy → Human and societal aspects of security and privacy; Human-centered computing → Human computer interaction (HCI); Interaction design; Additional Key Words and Phrases: Privacy, security, nudge, soft paternalism, behavioral economics This research has been supported by the National Science Foundation under grant CNS-1012763 (Nudging Users Towards Privacy), as well as grants CNS-0627513 and CNS-0905562, and by a Google Focused Re search Award. This research has also been supported by CMU CyLab under grants DAAD19-02-1-0389 and W911NF-09-1-0273 from the Army Research Office, the IWT SBO SPION Project, Nokia, France Telecom, and the CMU/Portugal Information and Communication Technologies Institute. -

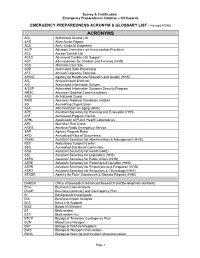

ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008

Survey & Certification Emergency Preparedness Initiative – All Hazards EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008 ACRONYMS AAL Authorized Access List AAR After-Action Report ACE Army Corps of Engineers ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices ACL Access Control List ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support ACF Administration for Children and Families (HHS) ACS Alternate Care Site ADP Automated Data Processing AFE Annual Frequency Estimate AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHS) AIE Annual Impact Estimate AIS Automated Information System AISSP Automated Information Systems Security Program AMSC American Satellite Communications ANG Air National Guard ANSI American National Standards Institute AO Accrediting Organization AoA Administration on Aging (HHS) APE Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (HHS) APF Authorized Program Facility APHL Association of Public Health Laboratories ARC American Red Cross ARES Amateur Radio Emergency Service ARF Agency Request Form ARO Annualized Rate of Occurrence ASAM Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management (HHS) ASC Ambulatory Surgical Center ASC Accredited Standards Committee ASH Assistant Secretary for Health (HHS) ASL Assistant Secretary for Legislation (HHS) ASPA Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (HHS) ASPE Assistant Secretary for Planning & Evaluation (HHS) ASPR Assistant Secretary for Preparedness & Response (HHS) ASRT Assistant Secretary for Resources & Technology (HHS) ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (HHS) BARDA -

Scottish Gaelic Style Guide

Scottish Gaelic Style Guide Contents What's New? .................................................................................................................................... 4 New Topics ................................................................................................................................... 4 Updated Topics ............................................................................................................................ 4 Introduction ...................................................................................................................................... 5 About This Style Guide ................................................................................................................ 5 Scope of This Document .............................................................................................................. 5 Style Guide Conventions .............................................................................................................. 5 Sample Text ................................................................................................................................. 6 Recommended Reference Material ............................................................................................. 7 Normative References .............................................................................................................. 7 Informative References ............................................................................................................