Handicrafts and Handloom Industry in Sikkim: Changes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Page 20 Backup Bulletin Format on Going

gkfnL] nfsjftf] { tyf ;:s+ lt[ ;dfh Nepali Folklore Society Nepali Folklore Society Vol.1 December 2005 The NFS Newsletter In the first week of July 2005, the research Exploring the Gandharva group surveyed the necessary reference materials related to the Gandharvas and got the background Folklore and Folklife: At a information about this community. Besides, the project office conducted an orientation programme for the field Glance researchers before their departure to the field area. In Introduction the orientation, they were provided with the necessary technical skills for handling the equipments (like digital Under the Folklore and Folklife Study Project, we camera, video camera and the sound recording device). have completed the first 7 months of the first year. During They were also given the necessary guidelines regarding this period, intensive research works have been conducted the data collection methods and procedures. on two folk groups of Nepal: Gandharvas and Gopalis. In this connection, a brief report is presented here regarding the Field Work progress we have made as well as the achievements gained The field researchers worked for data collection in from the project in the attempt of exploring the folklore and and around Batulechaur village from the 2nd week of July folklife of the Gandharva community. The progress in the to the 1st week of October 2005 (3 months altogether). study of Gopalis will be disseminated in the next issue of The research team comprises 4 members: Prof. C.M. Newsletter. Bandhu (Team Coordinator, linguist), Mr. Kusumakar The topics that follow will highlight the progress and Neupane (folklorist), Ms. -

Rikhi Ram Music Instrument Manufacturing Company

Rikhi Ram Music Instrument Manufacturing Company https://www.indiamart.com/rikhirammusicalinstruments/ Manufacturer of sarangi, dholak and teak wood sitar. About Us Indian instruments belong to a tradition dipped in antiquity. It dates back to the Veena of Saraswati, Bansuri of Krishna and Damru of Shiva, corresponding to modern classifications of musical instruments under string, wind & percussions respectively. The journey of 'Rikhi Ram Musical Instrument Mfg.Co' started with founder Late Pt. Rikhi Ram, who was a great musicians and one of the best known musical instrument maker. Pt. Rikhi Ram's father Pt. Gobind Ram was also a musician and had inclinations towards making musical instruments and so manufacturing of musical instruments started in the family 85 years ago. Pt. Rikhi Ram learnt sitar playing from eminent musician Abdul Harim Poonchwala. Late Pt. Bishan Dass followed in his father's footsteps and started learning sitar at a very tender age under the guidance and supervision of his father. Later, he became a disciple of world renowed sitar maestro Pt. Ravi Shankar. He also worked in the maintainance cell of A.I.R. During his tenor at A.I.R he got associated with great musicians like Ustad Allauddin Khan, Ustad Hafiz Ali Khan, Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pt.Ravi Shankar and many others. From these great Ustads Bishan learnt that the primal value of a good instrument was its tonal quality. They would often discuss these aspects of an instrument and give him useful hints. "This extra interest fired my imagination and aroused in me the urge to produce quality instruments for the maestros" says Late Pt. -

The Sarangi Family

THE SARANGI FAMILY 1. 1 Classification In the prestigious New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. the sarangi is described as follows : "A bowed chordophone occurring in a number of forms in the Indian subcontinent. It has a waisted body, a wide neck without frets and is usually carved from a single block of wood; in addition to its three or four strings it has one or two sets of sympathetic strings. The sarangi originated as a folk instrument but has been used increasingly in classical music." 1 Whereas this entry consists of only a few lines. the violin family extends to 72 pages. lea ding one to conclude that a comprehensive study of the sarangi has been sorely lacking for a long time. A cryptic description like the one above reveals next to nothing about this major Indian bowed instrument which probably originated at the same time as the violin. It also ignores the fact that the sarangi family comprises the largest number of Indian stringed instruments. What kind of sarangi did the authors visualize when they wrote these lines? Was it the large classical sarangi or one of the many folk types? In which musical context are these instruments used. and how important is the sarangi player? How does one play the sarangi? Who were the famous masters and what did they contribute? Many such questions arise when one talks about the sarangi. A person frnm Romhav-assuminq he is familiar with the sarangi-may have a different 2 picture in mind than someone from Jodhpur or Srinagar. -

Kutumba US Tour

KUTUMBA Kutumba, more than just performers Kutumba is a folk instrumental ensemble committed to the research, that will divide us as a people. preservation and celebration of the diversity that exists in indigenous In this unique time period as Nepal is going through a Nepali music. Kutumba firmly believes that the richness in Nepali complete re-evaluation of identity on all fronts, we are also faced music is directly significant of the rich diversity that exists in the with forces of globalization. This affects our young generations Nepali people. more than any other category of the Nepali population. As they As we become more aware of the multiculturalism in Nepali find themselves negotiating an identity that struggles not only society, be it in Kathmandu or other parts of the country, with hormones but national politics as well as global cultures political, social and developmental attention is trained on packaged attractively by television and other media, Kutumba recognizing differences and ensuring rights for our diverse feels now is a good time to reach out to young Nepalis and groups of people. Kutumba sees the possibility of finding respect encourage them to find respect, dignity and entertainment by promoting our multiculturalism through the medium of our through the creative and stabilizing energy and beauty of our indigenous music art forms as apposed to seeing it as a threat unique music art forms. Kutumba performs at the Janaki Temple in Janakpur, October 2008. L to R: Arun, Pavit, Binay, Siddhartha, Rubin, Raju and Kiran. BIOGRAPHY Arun Manandhar on Tungna, Arbajo Pavit Maharjan on Percussion Arun is one of the few musicians who play the Tungna today. -

Indian Music Instruments Sarangi Sitar Sitar Is of the Most Popular Music

Indian Music Instruments Sarangi Sitar Sitar is of the most popular music instruments of North India. The Sitar has a long neck with twenty metal frets and six to seven main cords. Below the frets of Sitar are thirteen sympathetic strings which are tuned to the notes of the Raga. A gourd, which acts as a resonator for the strings is at the lower end of the neck of the Sitar. The frets are moved up and down to adjust the notes. Some famous Sitar players are Ustad Vilayat Khan, Pt. Ravishankar, Ustad Imrat Khan, Ustad Abdul Halim Zaffar Khan, Ustad Rais Khan and Pt Debu Chowdhury. Sarod Sarod has a small wooden body covered with skin and a fingerboard that is covered with steel. Sarod does not have a fret and has twenty-five strings of which fifteen are sympathetic strings. A metal gourd acts as a resonator. The strings are plucked with a triangular plectrum. Some notable exponents of Sarod are Ustad Ali Akbar Khan, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan, Pt. Buddhadev Das Gupta, Zarin Daruwalla and Brij Narayan. Sarangi Sarangi is one of the most popular and oldest bowed instruments in India. The body of Sarangi is hollow and made of teak wood adorned with ivory inlays. Sarangi has forty strings of which thirty seven are sympathetic. The Sarangi is held in a vertical position and played with a bow. To play the Sarangi one has to press the fingernails of the left hand against the strings. Famous Sarangi maestros are Rehman Bakhs, Pt Ram Narayan, Ghulam Sabir and Ustad Sultan Khan. -

POST-MORTEM Round, and the Outcome Will Be Decided at the Party’S Upcoming Convention in Pokhara

#24 5 - 11 January 2001 20 pages Rs 20 EXCLUSIVE 69-41 The ruling party’s vicious internal power struggle is now in its final POST-MORTEM round, and the outcome will be decided at the party’s upcoming convention in Pokhara. But before In the 36 hours of mobocracy that ruled that, there was the small matter of Kathmandus streets last week, we caught the no-trust vote against Prime Minister Girija Prasad Koirala that a glimpse of an area of darkness in our wannabe Sher Bahadur Deuba countrys soul. wanted to settle first. The vote was set for 28 December, and both BINOD BHATTARAI factions did some grandstanding ○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○○ University. The government was not there at about secret or open ballot to hide n 26-27 December, Nepal had no a critical moment. It was only on Wednesday the fact that they were both terrified government. Legitimate political parties afternoon, after things began to get really out o of control that the Prime Ministers office of losing. cowered, citizens were afraid to speak Both sides met for the duel in out, the capital sank into an anarchic limbo. It began taking stock. The only party that the murky fog-shrouded Singha was all the more shocking because we had showed some sanity was the main opposition Durbar on Thursday morning. The been brought up to believe that things like this UML, which began drafting its now-famous rebels led by Deuba boycotted the werent supposed to happen in peaceful Nepal. statement warning people not to fish in vote when the Koirala camp It wont be the same again: Nepalis of all muddy waters. -

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments with the General

Classification of Indian Musical Instruments With the general background and perspective of the entire field of Indian Instrumental Music as explained in previous chapters, this study will now proceed towards a brief description of Indian Musical Instruments. Musical Instruments of all kinds and categories were invented by the exponents of the different times and places, but for the technical purposes a systematic-classification of these instruments was deemed necessary from the ancient time. The classification prevalent those days was formulated in India at least two thousands years ago. The first reference is in the Natyashastra of Bharata. He classified them as ‘Ghana Vadya’, ‘Avanaddha Vadya’, ‘Sushira Vadya’ and ‘Tata Vadya’.1 Bharata used word ‘Atodhya Vadya’ for musical instruments. The term Atodhya is explained earlier than in Amarkosa and Bharata might have adopted it. References: Some references with respect to classification of Indian Musical Instruments are listed below: 1. Bharata refers Musical Instrument as ‘Atodhya Vadya’. Vishnudharmotta Purana describes Atodhya (Ch. XIX) of four types – Tata, Avnaddha, Ghana and Sushira. Later, the term ‘Vitata’ began to be used by some writers in place of Avnaddha. 2. According to Sangita Damodara, Tata Vadyas are favorite of the God, Sushira Vadyas favourite of the Gandharvas, whereas Avnaddha Vadyas of the Rakshasas, while Ghana Vadyas are played by Kinnars. 3. Bharata, Sarangdeva (Ch. VI) and others have classified the musical instruments under four heads: 1 Fundamentals of Indian Music, Dr. Swatantra Sharma , p-86 53 i. Tata (String Instruments) ii. Avanaddha (Instruments covered with membrane) iii. Sushira (Wind Instruments) iv. Ghana (Solid, or the Musical Instruments which are stuck against one another, such as Cymbals). -

Identifying a Tribe of Sub-Himalaya : a Socio-Cultural Aspects Oftamang

Karatoya: NBU J. Hist. Vol. 5 :41-58 (2012) ISSN: 2229-4880 Identifying a Tribe of Sub-Himalaya : A Socio-Cultural Aspects ofTamang SudashLama The society is the repository of human behavior through the ages. It reflects the ideology and various cultural dimensions of mankind. The society is also a representative of civilization and, social structure is the indicator of organized human behavior. The folk songs of the Tamang tribe start with "Amailey Hoi Amaily "1, which praised the Motherhood, and indicate that ancient Tamang society was matriarchal (Tamang: BS 2051 ). Even today the position of the women in the social activities is equivalent of men and sometime the decision of women is more influential than men. The unification of Nepal by the great king Prithivinarayan Shah2 brought the idea ofHinduization. This process led to passing of the Act of 1854, which categorized the Tamang community as 'Bhote '3 and set into the lowest category of panichal Jaat4 or Shudras of Hindu caste hierarchy. The formation of social order that took form in Nepal followed patterns presaged in the greater social history of South Asia. As Dumont recounts, those who became Shudras in Indic varna ideology were originally conceived of as servants (Holmberg: 1996:26). The inclusion of the Tamang in the Hindu caste hierarchy especially in Nepal, also reflect the significant state ideology to bring this beef eater into the order of the Hindu cultural domain. But such inclusion by the state, with the identification as carrion-beef eater gave boost to the development of Tamang's 1. See Amailey Hoi Amailey, Amailey Hoi Amaily, Rapsi chiwa Chu Damphu, Khalse Shemba Bilawa, means "Praising the Mother, and admiring the Mother, saying that the instrument that I am beating, who is the its maker" Santabir Lama Pakhrin 's Tamba Kaiten Whai Rimthim (Sam vat 2064 ), Ratna Pustak Bhandar, Kathmandu, Nepal,(p 08) 2. -

Can You Hear the Music? World Music Day Is Right Around the Corner

Every Thursday ISSUE 226 RS 40 26 JUNE 2014 12 ciff( 2071 Can You Hear The Music? World Music Day is right around the corner. Although the scene is thriving, there are those who have been ruing the lack of government support. 4 Newsfeed k ckstart TOP 3 EVENTS “ThE LADY” in nEPAL: A BRIEF TIMMELINE EXPERIENCE THAILAND Aung San Suu Kyi is the daughter of Foodies, get ready to excite your taste buds with exotic food Burma’s independence hero, General from Thailand! Celebration of Thailand, hosted by Hotel Aung San, who was assassinated in de L’ Annapurna on 18 and 19 June, will feature exquisite July 1947, just six months prior to !culinary creations by famous Thai chefs, and exotic Thai the country gaining independence fashion accompanied by Thai music. The event will also from Britain. Suu Kyi was only two present The Nepal-Thai Fashion Show that will have outfits when her father was killed. by popular Thai designers and four Nepali designers, as well 1960: Suu Kyi went to India with as a performance by a famous Thai band. The event also her mother Daw Khin Kyi, who had includes a cooking class facilitated by a renowned Thai chef been appointed Burma’s ambassador on 19 June. The event is organized by Royal Thai Embassy to Delhi. and Nepal-Thailand Co-operation Society in alliance with Hotel de L’ Annapurna. 1964: She went to Oxford University in the UK, where she studied Date: 18 & 19 June, Time: 7pm onwards, Contact: 4221711 Venue: Poolside Garden, Hotel de L› Annapurna, Durbar Marg philosophy, politics, and economics. -

Times in India, EKT Edition

This is a daily collection of all sorts of interesting stuff for you to read about during the trip. The guides can’t cover everything; so this is a way for me to fill in some of those empty spaces about many of the different aspects of this fascinating culture. THE Once Upon a TIMES OF INDIA PUBLISHED FOR EDDIE’S KOSHER TRAVEL GUESTS, WITH TONGUE IN CHEEK OCTOBER 2014 בן בג בג אומר: ”הפוך בה והפוך בה, דכולא בה“ )אבות ה‘( INDIA! - An Explorer’s Note Thanks to Eddie’s Kosher still dark. Thousands of peo- concept completely. Do not WELCOME Travel and you, I am coming ple were all over the place look upon India with western back to India now for the waiting for trains, I imagine, eyes, and do not judge it. If TO INDIA! 25th time; and every time I’m and sleeping on the station you do, you will diminish not quite sure what type of platforms. Here too, many both it and your experience. India I will find. Over the beggars are already at "work" Learn it. Feel it. Imbibe it. years that I have travelled coming up to me with hands Accept it. Wrap your head here regularly, I have grown outstretched. While I under- around it. Understand it for to love India, specially its stand the Indian worldview of what it is. For it is India. people, who seemed to have caste and karma, and why by an attitude of "there is always and large no one helps the When I was here for the first room for one more." I find poverty stricken, I find it time in 1999, India’s popula- the people in India to be pa- very, very disturbing. -

Viranam India Private Limited

+91-8046069470 Viranam India Private Limited https://www.indiamart.com/viranamindia/ We “Indian Cultura” are a leading Manufacturer of a wide range of Wooden Harmonium, Wooden Dhol, Wooden Tabla, Wooden Sarangi, etc. About Us Established as a Sole Proprietorship firm in the year 2017, we “Viranam India Private Limited” are a leading Manufacturer of a wide range of Wooden Harmonium, Wooden Dhol, Wooden Tabla, Wooden Sarangi, etc. Situated in Jaipur (Rajasthan, India), we have constructed a wide and well functional infrastructural unit that plays an important role in the growth of our company. We offer these products at reasonable rates and deliver these within the promised time-frame. Under the headship of “Mr. Krishan Soni” (Owner), we have gained a huge clientele across the nation. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/viranamindia/aboutus.html WOODEN HARMONIUM O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e 42 Keys Wooden Harmonium 37 Keys Wooden Harmonium 42 Keys 9 Stopper 39 Key 7 Stopper Harmonium Harmonium Double Bellow WOODEN DHOLAK O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Wooden Dholak Wood Dholak Dholki Folk Musical Instrument Drum Nuts N Bolt Musical Rope Dholak Wooden Dholak Folk Musical Sheesham Wood Folk Instrument Drum Nuts N Bolt Traditional Musical Instrument With Cover PERCUSSION INSTRUMENTS O u r P r o d u c t R a n g e Thavil Percussion Instrument Beautiful Handcrafted Designer Damru Musical Instrument Wooden Rope Shiva Damru Classical Woodwind Musical Indian Musical Instrument Instruments Wedding Classical Wind Shehnai Processions -

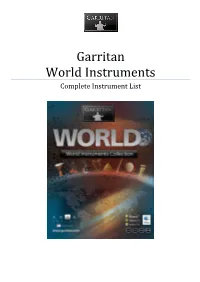

Garritan World Instruments Complete Instrument List

Garritan World Instruments Complete Instrument List Garritan: World Instruments Complete Instrument List Africa: Sakara India: Sangban Arghul Bansuri 1 Sanza Mijwiz 1 Bansuri 2 Sistrum Mijwiz 2 Pungi Snake Charmer Tama (Talking Drum) Adodo Shenai Televi African Log Drum Shiva Whistle Tonetang (Stir Drum) Apentima Basic Indian Percussion Udu Drums Ashiko Chenda Begena Balafon Chimta Bolon Basic African Percussion Chippli Domu Bougarabou Dafli Kora Dawuro Damroo Ngoni Djembe Dhol Dondo China: Dholak Doun Ba Bawu Ghatam Atoke Di-Zi Ghungroo Axatse Guanzi Gong (Stinging Gong) Gankokwe Hulusi Hatheli Kagan Sheng Kanjeera Kpanlogo 1 Large Suona Khartal Kpanlogo 2 Medium Xiao Khol Kpanlogo 3 Combo Basic Chinese Percussion Manjeera Sogo Bianzhong Murchang Fontomfrom Bo Mridangam Gome Chinese Cymbals Naal Gyil Chinese Gongs Nagara Ibo Datangu Lion Drum Pakhawaj Kalimbas Pan Clappers Stir Drum Kenkeni Temple Bells Tablas Kpoko Kpoko Temple Blocks Tamte Krin Slit Drum Choazhou Guzheng Tasha Likembe Erhu Tavil Mbira Guzheng Udaku Morocco Drum Pipa Electric Sitar Nigerian Log Drum Yueqin Sarangi Sarangi Drone Thai Gong Uilleann Pipes Sitar Tibetan Cymbals Bone Flute 1 Tambura Tibetan Singing Bowls Bone Flute 2 Japan: Tibetan Bells Irish Flute Tingsha Shepherds Folk Pipe 1 Hichiriki Dan Tranh Shepherds Folk Pipe 2 Knotweed Flute Dan Ty Ba Bodhran Shakuhachi Gopichand Hang Drum Chanchiki Jaw Harps Chu-daiko Europe: Rattle Cog Daibyoshi Double Flute Hira-Daiko Dvojnice Double Flute Latin America: Hyoushigi Double Flute Drone Andean Panpipes Ko-Daiko