Information to Users

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director.—Michael Mastrian Deputy Director.—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator.—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinator.—Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director.—Tina Tate Deputy Director.—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistant for Administrative Operations.—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations.—Andy Elias Assistants: Gerald Rupert, Kimberly Oates EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

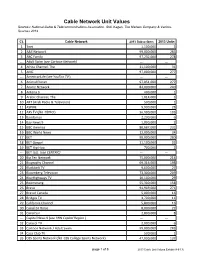

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, the Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013

Cable Network Unit Values Sources: National Cable & Telecommunications Association, SNL Kagan, The Nielsen Company & Various Sources 2013 Ct. Cable Network 2013 Subscribers 2013 Units 1 3net 1,100,000 3 2 A&E Network 99,000,000 283 3 ABC Family 97,232,000 278 --- Adult Swim (see Cartoon Network) --- --- 4 Africa Channel, The 11,100,000 31 5 AMC 97,000,000 277 --- AmericanLife (see YouToo TV ) --- --- 6 Animal Planet 97,051,000 277 7 Anime Network 84,000,000 240 8 Antena 3 400,000 1 9 Arabic Channel, The 1,014,000 3 10 ART (Arab Radio & Television) 500,000 1 11 ASPIRE 9,900,000 28 12 AXS TV (fka HDNet) 36,900,000 105 13 Bandamax 2,200,000 6 14 Bay News 9 1,000,000 2 15 BBC America 80,687,000 231 16 BBC World News 12,000,000 34 17 BET 98,000,000 280 18 BET Gospel 11,100,000 32 19 BET Hip Hop 700,000 2 --- BET Jazz (see CENTRIC) --- --- 20 Big Ten Network 75,000,000 214 21 Biography Channel 69,316,000 198 22 Blackbelt TV 9,600,000 27 23 Bloomberg Television 73,300,000 209 24 BlueHighways TV 10,100,000 29 25 Boomerang 55,300,000 158 26 Bravo 94,969,000 271 27 Bravo! Canada 5,800,000 16 28 Bridges TV 3,700,000 11 29 California Channel 5,800,000 16 30 Canal 24 Horas 8,000,000 22 31 Canal Sur 2,800,000 8 --- Capital News 9 (see YNN Capital Region ) --- --- 32 Caracol TV 2,000,000 6 33 Cartoon Network / Adult Swim 99,000,000 283 34 Casa Club TV 500,000 1 35 CBS Sports Network (fka CBS College Sports Network) 47,900,000 137 page 1 of 8 2013 Cable Unit Values Exhibit (4-9-13) Ct. -

Wednesday November 14, 2012

Wednesday November 14, 2012 8:00 AM 002024 8:00 AM to 5:00 PM Dolphin Europe 7 - Third/Lobby Level SEMINAR: Celebrating the COMMunity that Diversely “Does Disney”: Multi -disciplinary and Multi -institutional Approaches to Researching and Teaching About the "World" of Disney Sponsor: Seminars Chairs: Mary-Lou Galician, Arizona State University; Amber Hutchins, Kennesaw State University Presenters: Emily Adams, Abilene Christian University Sharon D. Downey, California State Univ, Long Beach Erika Engstrom, University of Nevada, Las Vegas Sandy French, Radford University Mary-Lou Galician, Arizona State University Cerise L. Glenn, Univ of North Carolina, Greensboro Jennifer A. Guthrie, University of Kansas Jennifer Hays, University of Bergen, Norway Amber Hutchins, Kennesaw State University Jerry L. Johnson, Buena Vista University Lauren Lemley, Abilene Christian University Debra Merskin, University of Oregon David Natharius, Arizona State University Tracey Quigley Holden, University of Delaware Kristin Scroggin, University of Alabama, Huntsville David Zanolla, Western Illinois University 002025 8:00 AM to 12:00 PM Dolphin Europe 8 - Third/Lobby Level SEMINAR: COMMunity Impact: Defining the Discipline and Equipping Our Students to Make Everyday Differences Sponsor: Seminars Chair: Darrie Matthew Burrage, Univ of Colorado, Boulder Presenters: Jeremy R. Grossman, University of Georgia Margaret George, Univ of Colorado, Boulder Katie Kethcart, Colorado State University Ashton Mouton, Purdue University Emily Sauter, University of Wisconsin, Madison Eric Burrage, University of Pittsburgh 002027 8:00 AM to 3:45 PM Dolphin Europe 10 - Third/Lobby Level SEMINAR: The Dissertation Writing Journey Sponsor: Seminars Chairs: Sonja K. Foss, Univ of Colorado, Denver; William Waters, University of Houston, Downtown 8:30 AM 003007 8:30 AM to 5:00 PM Dolphin Oceanic 3 - Third/Lobby Level PC02: Moving Methodology: 2012 Organizational Communication Division Preconference Sponsor: Preconferences Presenters: Karen Lee Ashcraft, University of Colorado, Boulder J. -

For Immediate Release

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE CONTACTS: Ashley Berke Lauren Saul Director of Public Relations Public Relations Manager 215.409.6693 215.409.6895 [email protected] [email protected] INSPIRING STUDENTS TO SERVE IS GOAL OF NATIONAL CONSTITUTION CENTER WEBCAST ON DR. MARTIN LUTHER KING, JR. Program available in classrooms nationwide through Channel One Connection Philadelphia, PA (January 3, 2012) – More than two decades ago, President Ronald Reagan declared Martin Luther King, Jr. Day as a day to honor the life and legacy of one of the most inspiring figures in American history. In celebration of the profound accomplishments of Dr. King, the National Constitution Center presents Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Legacy of Service, the latest episode of the popular webcast series Constitution Hall Pass. Students will have the opportunity to explore Dr. King’s use of nonviolent protest and learn about other famous activists who drew inspiration from him. The episode will be available in classrooms nationwide throughout the months of January and February via Channel One Connection, a commercial-free educational programming resource available to Channel One Network member schools. The webcast also will be available at www.constitutioncenter.org/hallpass. From Monday, January 9 through Friday, January 13, 2012, and on Martin Luther King, Jr. Day on January 16, 2012, students and teachers can chat live with the National Constitution Center’s education staff from 7:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. EST as they answer questions and offer additional insight on Dr. King’s life. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.: A Legacy of Service traces moments in Dr. -

Lista Ofrecida Por Mashe De Forobeta. Visita Mi Blog Como Agradecimiento :P Y Pon E Me Gusta En Forobeta!

Lista ofrecida por mashe de forobeta. Visita mi blog como agradecimiento :P Y pon e Me Gusta en Forobeta! http://mashet.com/ Seguime en Twitter si queres tambien y avisame que sos de Forobeta y voy a evalu ar si te sigo o no.. >>@mashet NO ABUSEN Y SIGAN LOS CONSEJOS DEL THREAD! http://blog.newsarama.com/2009/04/09/supernaturalcrimefightinghasanewname anditssolomonstone/ http://htmlgiant.com/?p=7408 http://mootools.net/blog/2009/04/01/anewnameformootools/ http://freemovement.wordpress.com/2009/02/11/rlctochangename/ http://www.mattheaton.com/?p=14 http://www.webhostingsearch.com/blog/noavailabledomainnames068 http://findportablesolarpower.com/updatesandnews/worldresponsesearthhour2009 / http://www.neuescurriculum.org/nc/?p=12 http://www.ybointeractive.com/blog/2008/09/18/thewrongwaytochooseadomain name/ http://www.marcozehe.de/2008/02/29/easyariatip1usingariarequired/ http://www.universetoday.com/2009/03/16/europesclimatesatellitefailstoleave pad/ http://blogs.sjr.com/editor/index.php/2009/03/27/touchinganerveresponsesto acolumn/ http://blog.privcom.gc.ca/index.php/2008/03/18/yourcreativejuicesrequired/ http://www.taiaiake.com/27 http://www.deadmilkmen.com/2007/08/24/leaveusaloan/ http://www.techgadgets.in/household/2007/06/roboamassagingchairresponsesto yourvoice/ http://blog.swishzone.com/?p=1095 http://www.lorenzogil.com/blog/2009/01/18/mappinginheritancetoardbmswithst ormandlazrdelegates/ http://www.venganza.org/about/openletter/responses/ http://www.middleclassforum.org/?p=405 http://flavio.castelli.name/qjson_qt_json_library http://www.razorit.com/designers_central/howtochooseadomainnameforapree -

Commercialism in Public Schools: Focusing on Channel One

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 471 593 SO 034 456 AUTHOR Aiken, Margaret Putman TITLE Commercialism in Public Schools: Focusing on Channel One. PUB DATE 2000-00-00 NOTE 49p.; Scholarly study submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Specialist in Education, Georgia State University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses (040) Reports Research (143) Tests /Questionnaires (160) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; *Current Events; Data Collection; Educational Research; Grade 8; Pretests Posttests; *Public Schools; Secondary Education; Sex Differences IDENTIFIERS *Channel One; *Commercialism; Georgia; T Test ABSTRACT A study measured the effectiveness of the Channel One news program on student achievement in current events. Data were collected to measure the difference in current events knowledge between those students who viewed and discussed Channel One, and those students who had no access to the program. Data based on gender differences in student achievement was also measured. A 20-item multiple choice pre- and post-test was designed by the researcher and administered to eighth graders (n=78) in an urban high school near Atlanta, Georgia, during winter 2000. A school that contracts with Channel One receives a satellite dish, two videotape recorders for automatic recording of the televised broadcasts, and networked televisions. The daily feed is a 12-minute program, 10 minutes of news and features, and two minutes of advertisements. The contract runs for a 3-year period in which the school promises to show Channel One on 90% of all school days and in 80% of all classrooms. Currently, an estimated 8 million junior and senior high school students representing 12,000 schools view Channel One each day. -

The Effect of Channel One Broadcasts on Middle School Achievement

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 358 010 SO 023 044 AUTHOR Houston, Carol TITLE The Effect of Channel One Broadcasts on Middle School Achievement. PUB DATE 7 Dec 92 NOTE 45p.; Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for ASE 579, Sam Houston State University. PUB TYPE Dissertations/Theses Undetermined (040) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Classroom Research; *Current Events; *Discussion (Teaching Technique); Educational Research; Junior High Schools; Junior High School Students; Middle Schools; *News Media; *Programing (Broadcast); Television Research; *Television Viewing IDENTIFIERS *Channel One; Middle School Students ABSTRACT A study was conducted to determine if classroom discussion of Channel One broadcasts would increase student knowledge of current events. Channel One is a news program designed for middle school and high school students and is shown to participating schools across the United States. The program is free to schools that receive use of a satellite dish, video recorders, and television monitors. In exchange for the equipment, schools must require students to watch the program daily. Many educators agree that the news broadcast is important, but contention centers around a two minute segment of commercials. The advertising pays for the program and equipment. Data were collected in three areas: a current events test was given to two groups of students, one group actively involved in a classroom discussion of the day's broadcast and one group who had been exposed to the program but was not involved in the discussion. Other data were gathered to solicit teacher sentiment of Channel One as a teaching device and a survey also was used to determine student application of Channel One as a learning tool. -

Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (85Th, Miami, Florida, August 5-8, 2002). Radio-Television Journalism Division

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 473 792 CS 511 777 TITLE Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (85th, Miami, Florida, August 5-8, 2002). Radio-Television Journalism Division. PUB DATE 2002-08-00 NOTE 325p.; For other sections of these proceedings, see CS 511 769-787. PUB TYPE Collected Works Proceedings (021) Reports Research (143) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF01/PC14 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Broadcast Journalism; Chinese; Cross Cultural Studies; *Elections; Emotional Response; Ethics; Facial Expressions; Higher Education; *Journalism Education; *Mass Media Effects; Mass Media Role; Media Coverage; *Presidential Campaigns (United States); Radio; Sex Bias IDENTIFIERS News Sources; September 11 Terrorist Attacks 2001; Sesame Street; *Television News; *Weather Forecasting ABSTRACT The Radio-Television Journalism Division of the proceedings contains the following 12 papers: "Chinese-Language Television News in the U.S.A.: A Cross-Cultural Examination of News Formats and Sources" (Yih-Ling Liu and Tony Rimmer); "News Diffusion and Emotional Response to the September 11 Attacks" (Stacey Frank Kanihan and Kendra L. Gale); "Pacing in Television Newscasts: Does Target Audience Make a Difference?" (Mark Kelley); "The Myth of the Five-Day Forecast: A Study of Television Weather Accuracy and Audience Perceptions of Accuracy in Columbus, Ohio" (Jeffrey M. Demas); "Visual Bias in Broadcasters' Facial Expressions and Other Factors Affecting Voting Behavior of TV News Viewers in a Presidential Election" (Renita Coleman and Donald Granberg); "The Real Ted Baxter: The Rise of the Celebrity Anchorman" (Terry Anzur); "Do Sweeps Really Affect a Local News Program?: An Analysis of KTVU Evening News During the 2001 May Sweeps" (Yonghoi Song); "Stories in Dark Places: David Isay and the New Radio Documentary" (Matthew C. -

Student and Teacher Perspectives on Channel One: a Qualitsi:.Je Study of Participants in Massachusetts and Florida Schools

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 390 090 CS 509 112 AUTHOR Barrett, Janice M. TITLE Student and Teacher Perspectives on Channel One: A Qualitsi:.Je Study of Participants in Massachusetts and Florida Schools. PUB DATE Aug 95 NOTE 39p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication (78th, Washington, DC, August 9-12, 1995). PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) Reports Research/Technical (143) EDRS PRICE MF01/PCO2 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Critical Viewing; Interviews; *Mass Media Use; Qualitative Research; Secondary Education; *Student Attitudes; *Teacher Attitudes; Television Research; *Television Viewing IDENTIFIERS *Channel One; Florida; Focus Groups; Massachusetts; Middle School Students ABSTRACT A study of Channel One, the 10 minutes of television news programs and 2 minutes of commercials in classrooms, described the opinions and evaluative comments of participant teachers, librarians, administrators, and students. Individual interviews and focus group discussions were conducted at eight secondary schools (four in Florida and four in Massachusetts)over a 16-month period. Use of Channel One was also observed in the classrooms. Results indicated that the benefits of Channel Oneare student-heightened interest in geography, current events, andpop quizzes; and that the disadvantages are the commercials, the superficial programming, the intrusion into the school day, the lack of integration into the curriculum, the lack of inclusion of teachers in the policy decision to contract with Channel One, and the superficial television emphasis on visuals, graphics, and motion. Results also indicated that Channel One appeared to be most appropriate for middle school students. Recommendations include involving teachers in the decision-making process regarding Channel One, targeting a middle-school audience, encouraging teachers to develop curriculum units for critical viewing of Channel One, and developing assessment and evaluation procedures for Channel One's use and its effectiveness. -

Universidade Federal De Santa Catarina, Como Requisito Parcial Para Obtenção Do Grau De Mestre Em Educação

CENTRO DE CIÊNCIAS DA EDUCAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO EM EDUCAÇÃO Leopoldo Nogueira e Silva TELEJORNAIS E CRIANÇAS NO BRASIL: A PONTA DO ICEBERG Florianópolis 2011 Leopoldo Nogueira e Silva TELEJORNAIS E CRIANÇAS NO BRASIL: A PONTA DO ICEBERG Dissertação submetida ao Programa de Pós- Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, como requisito parcial para obtenção do Grau de Mestre em Educação. Orientadora: Profa. Dra. Monica Fantin Florianópolis 2011 Catalogação na fonte elaborada pela biblioteca da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina S586t Silva, Leopoldo Nogueira e. Telejornais e crianças no Brasil [dissertação] : a ponta do iceberg / Leopoldo Nogueira e Silva ; orientadora, Monica Fantin. – Florianópolis, SC, 2011. 1 v. : il. Dissertação (mestrado) – Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Centro de Ciências da Educação. Programa de Pós- Graduação em Educação. Inclui referências 1. Educação. 2. Telejornalismo – Crianças . 3. Telejornalismo - Brasil. 4. Televisão e crianças. I. Fantin, Monica. II. Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. III. Título CDU 37 Leopoldo Nogueira e Silva TELEJORNALISMO PARA CRIANÇAS NO BRASIL: A PONTA DO ICEBERG Esta Dissertação foi julgada adequada para obtenção do Título de ―Mestre‖, e aprovada em sua forma final pelo Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação da Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina. Florianópolis, 06 de dezembro de 2011. ________________________ Profª Célia Regina Vendramini, Dra. Coordenadora do Curso Banca Examinadora: ________________________ Profª. Monica Fantin, Dr. Orientadora Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ________________________ Prof. Francisco José Castilhos Karam, Dr. Examinador Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina ________________________ Profª. Inês Sílvia Vitorino Sampaio, Dra. Examinador Universidade Federal do Ceará ________________________ Profª. -

Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries* Rules Governing Radio and Television Correspondents' Galleries

RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES* SENATE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room S–325, 224–6421 Director—Lawrence J. Janezich Deputy Director—Jane Ruyle Senior Media Coordinator—Michael Lawrence Media Coordinators: Michael Mastrian, Sara Robertson HOUSE RADIO AND TELEVISION GALLERY The Capitol, Room H–321, 225–5214 Director—Tina Tate Deputy Director—Beverly Braun Assistant for Administrative Operations—Gail Davis Assistant for Technical Operations—Olga Ramirez Kornacki Assistants: Andrew Elias, Gerald Rupert EXECUTIVE COMMITTEE OF THE RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES Joe Johns, NBC News, Chair Jerry Bodlander, Associated Press Radio Bob Fuss, CBS News Edward O’Keefe, ABC News Dave McConnell, WTOP Radio Richard Tillery, The Washington Bureau David Wellna, NPR News RULES GOVERNING RADIO AND TELEVISION CORRESPONDENTS’ GALLERIES 1. Persons desiring admission to the Radio and Television Galleries of Congress shall make application to the Speaker, as required by Rule 34 of the House of Representatives, as amended, and to the Committee on Rules and Administration of the Senate, as required by Rule 33, as amended, for the regulation of Senate wing of the Capitol. Applicants shall state in writing the names of all radio stations, television stations, systems, or news-gathering organizations by which they are employed and what other occupation or employment they may have, if any. Applicants shall further declare that they are not engaged in the prosecution of claims or the promotion of legislation pending before Congress, the Departments, or the independent agencies, and that they will not become so employed without resigning from the galleries. They shall further declare that they are not employed in any legislative or executive department or independent agency of the Government, or by any foreign government or representative thereof; that they are not engaged in any lobbying activities; that they *Information is based on data furnished and edited by each respective gallery. -

Networks, Stations, and Services Represented

NETWORKS, STATIONS, AND SERVICES REPRESENTED Senate Gallery 224–6421 House Gallery 225–5214 ABC NEWS—(202) 222–7700; 1717 DeSales Street, NW., Washington, DC 20036: John W. Allard, Scott Anderson, Sarah Baker, Mark Banks, Gene Barrett, Sonya Crawford Bearson, Adam Belmar, Bob Bender, Phillip M. Black, Tahman Bradley, Robert E. Bramson, Charles Breiterman, Sam Brooks, Henry M. Brown, David John G. Bull, Quiana Burns, Christopher Carlson, David Chalian, Martin J. Clancy, John Cochran, Theresa E. Cook, Richard L. Coolidge, Pam Coulter, Jan Crawford Greenburg, Max Culhane, Thomas J. d’Annibale, Jack Date, Edward Teddy Davis, Yunji Elisabeth de Nies, Clifford E. DeGray, Steven Densmore, Dominic DeSantis, Elizabeth C. Dirner, Henry Disselkamp, John F. Dittman, Peter M. Doherty, Brian Donovan, Lawrence L. Drumm, Jennifer Duck, Richard Ehrenberg, Margaret Ellerson, Daniel Glenn Elvington, Kendall A. Evans, Charles Finamore, Jon D. Garcia, Robert G. Garcia, Arthur R. Gauthier, Charles DeWolf Gibson, Thomas M. Giusto, Bernard Gmiter, Jennifer Goldberg, Stuart Gordon, Robin Gradison, Jonathan Greenberger, Stephen Hahn, Brian Robert Hartman, William T. Hatch, John Edward Hendren, Esequiel Herrera, Kylie A. Hogan, Julia Kartalia Hoppock, Matthew Alan Hosford, Amon Hotep, Bret Hovell, Matthew Jaffe, Fletcher Johnson, Kenneth Johnson, Derek Leon Johnston, Akilah N. Joseph, Steve E. Joya, James F. Kane, Jonathan Karl, David P. Kerley, John Knott, Donald Eugene Kroll, Maya C. Kulycky, Hilary Lefebvre, Melissa Anne Lopardo, Ellsworth M. Lutz, Lachlan Murdoch MacNeil, Liz Marlantes, James Martin, Jr., Luis Martinez, Darraine Maxwell, Michele Marie McDermott, Erik T. McNair, Ari Meltzer, Portia Migas, Avery Miller, Sunlen Mari Miller, Keith B. Morgan, Gary Nadler, Emily Anne Nelson, Dean E.