Peveril Castle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009

Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire, 2008 and 2009 Catherine Collins 2 Archaeological Test Pit Excavations in Castleton, Derbyshire in 2008 and 2009 By Catherine Collins 2017 Access Cambridge Archaeology Department of Archaeology and Anthropology University of Cambridge Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QG 01223 761519 [email protected] http://www.access.arch.cam.ac.uk/ (Front cover images: view south up Castle Street towards Peveril Castle, 2008 students on a trek up Mam Tor and test pit excavations at CAS/08/2 – copyright ACA & Mike Murray) 3 4 Contents 1 SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 7 2 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................... 8 2.1 ACCESS CAMBRIDGE ARCHAEOLOGY ..................................................................................................... 8 2.2 THE HIGHER EDUCATION FIELD ACADEMY ............................................................................................ 8 2.3 TEST PIT EXCAVATION AND RURAL SETTLEMENT STUDIES ...................................................................... 9 3 AIMS, OBJECTIVES AND DESIRED OUTCOMES ........................................................................ 10 3.1 AIMS .......................................................................................................................................................... -

The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area

I Contrebis 2000 The Early History of Man's Activities in the Quernmore Area. Phil Hudson Introduction This paper hopes to provide a chronological outline of the events which were important in creating the landscape changes in the Quernmore forest area. There was movement into the area by prehistoric man and some further incursions in the Anglo- Saxon and the Norse periods leading to Saxon estates and settled agricultural villages by the time of the Norman Conquest. These villages and estates were taken over by the Normans, and were held of the King, as recorded in Domesday. The Post-Nonnan conquest new lessees made some dramatic changes and later emparked, assarted and enclosed several areas of the forest. This resulted in small estates, farms and vaccaries being founded over the next four hundred years until these enclosed areas were sold off by the Crown putting them into private hands. Finally there was total enclosure of the remaining commons by the 1817 Award. The area around Lancaster and Quernmore appears to have been occupied by man for several thousand years, and there is evidence in the forest landscape of prehistoric and Romano-British occupation sites. These can be seen as relict features and have been mapped as part of my on-going study of the area. (see Maps 1 & 2). Some of this field evidence can be supported by archaeological excavation work, recorded sites and artif.act finds. For prehistoric occupation in the district random finds include: mesolithic flints,l polished stone itxe heads at Heysham;'worked flints at Galgate (SD 4827 5526), Catshaw and Haythomthwaite; stone axe and hammer heads found in Quernmore during the construction of the Thirlmere pipeline c1890;3 a Neolithic bowl, Mortlake type, found in Lancaster,o a Bronze Age boat burial,s at SD 5423 5735: similar date fragments of cinerary urn on Lancaster Moor,6 and several others discovered in Lancaster during building works c1840-1900.7 Several Romano-British sites have been mapped along with finds of rotary quems from the same period and associated artifacts. -

Culture Derbyshire Papers

Culture Derbyshire 9 December, 2.30pm at Hardwick Hall (1.30pm for the tour) 1. Apologies for absence 2. Minutes of meeting 25 September 2013 3. Matters arising Follow up on any partner actions re: Creative Places, Dadding About 4. Colliers’ Report on the Visitor Economy in Derbyshire Overview of initial findings D James Followed by Board discussion – how to maximise the benefits 5. New Destination Management Plan for Visit Peak and Derbyshire Powerpoint presentation and Board discussion D James 6. Olympic Legacy Presentation by Derbyshire Sport H Lever Outline of proposals for the Derbyshire ‘Summer of Cycling’ and discussion re: partner opportunities J Battye 7. Measuring Success: overview of performance management Presentation and brief report outlining initial principles JB/ R Jones for reporting performance to the Board and draft list of PIs Date and time of next meeting: Wednesday 26 March 2014, 2pm – 4pm at Creswell Crags, including a tour Possible Bring Forward Items: Grand Tour – project proposal DerbyShire 2015 proposals Summer of Cycling MINUTES of CULTURE DERBYSHIRE BOARD held at County Hall, Matlock on 25 September 2013. PRESENT Councillor Ellie Wilcox (DCC) in the Chair Joe Battye (DCC – Cultural and Community Services), Pauline Beswick (PDNPA), Nigel Caldwell (3D), Denise Edwards (The National Trust), Adam Lathbury (DCC – Conservation and Design), Kate Le Prevost (Arts Derbyshire), Martin Molloy (DCC – Strategic Director Cultural and Community Services), Rachael Rowe (Renishaw Hall), David Senior (National Tramway Museum), Councillor Geoff Stevens (DDDC), Anthony Streeten (English Heritage), Mark Suggitt (Derwent Valley Mills WHS), Councillor Ann Syrett (Bolsover District Council) and Anne Wright (DCC – Arts). Apologies for absence were submitted on behalf of Huw Davis (Derby University), Vanessa Harbar (Heritage Lottery Fund), David James (Visit Peak District), Robert Mayo (Welbeck Estate), David Leat, and Allison Thomas (DCC – Planning and Environment). -

Boar Hunting Weapons of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Doug Strong

Boar Hunting Weapons of the Late Middle Ages and Renaissance Doug Strong When one thinks of weapons for hunting, two similar devices leap to mind, the bow and the crossbow. While it is true that these were used extensively by hunters in the middle ages and the renaissance they were supplemented by other weapons which provided a greater challenge. What follows is an examination of the specialized tools used in boar hunting, from about 1350- 1650 CE. It is not my intention to discuss the elaborate system of snares, pits, nets, and missile weapons used by those who needed to hunt but rather the weapons used by those who wanted to hunt as a sport. Sport weapons allowed the hunters to be in close proximity to their prey when it was killed. They also allowed the hunters themselves to pit their own strength against the strength of a wild boar and even place their lives in thrilling danger at the prospect of being overwhelmed by these wild animals. Since the dawn of time mankind has engaged in hunting his prey. At first this was for survival but later it evolved into a sport. By the middle ages it had become a favorite pastime of the nobility. It was considered a fitting pastime for knights, lords, princes and kings (and later in this period, for ladies as well!) While these people did not need to provide the game for their tables by their own hand, they had the desire to participate in an exciting, violent, and even dangerous sport! For most hunters two weapons were favored for boar hunting; the spear and the sword. -

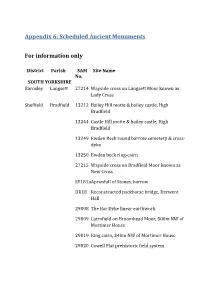

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments for Information Only

Appendix 6: Scheduled Ancient Monuments For information only District Parish SAM Site Name No. SOUTH YORKSHIRE Barnsley Langsett 27214 Wayside cross on Langsett Moor known as Lady Cross Sheffield Bradfield 13212 Bailey Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13244 Castle Hill motte & bailey castle, High Bradfield 13249 Ewden Beck round barrow cemetery & cross- dyke 13250 Ewden beck ring-cairn 27215 Wayside cross on Bradfield Moor known as New Cross SY181a Apronfull of Stones, barrow DR18 Reconstructed packhorse bridge, Derwent Hall 29808 The Bar Dyke linear earthwork 29809 Cairnfield on Broomhead Moor, 500m NW of Mortimer House 29819 Ring cairn, 340m NW of Mortimer House 29820 Cowell Flat prehistoric field system 31236 Two cairns at Crow Chin Sheffield Sheffield 24985 Lead smelting site on Bole Hill, W of Bolehill Lodge SY438 Group of round barrows 29791 Carl Wark slight univallate hillfort 29797 Toad's Mouth prehistoric field system 29798 Cairn 380m SW of Burbage Bridge 29800 Winyard's Nick prehistoric field system 29801 Ring cairn, 500m NW of Burbage Bridge 29802 Cairns at Winyard's Nick 680m WSW of Carl Wark hillfort 29803 Cairn at Winyard's Nick 470m SE of Mitchell Field 29816 Two ring cairns at Ciceley Low, 500m ESE of Parson House Farm 31245 Stone circle on Ash Cabin Flat Enclosure on Oldfield Kirklees Meltham WY1205 Hill WEST YORKSHIRE WY1206 Enclosure on Royd Edge Bowl Macclesfield Lyme 22571 barrow Handley on summit of Spond's Hill CHESHIRE 22572 Bowl barrow 50m S of summit of Spond's Hill 22579 Bowl barrow W of path in Knightslow -

The Story of a Man Called Daltone

- The Story of a Man called Daltone - “A semi-fictional tale about my Dalton family, with history and some true facts told; or what may have been” This story starts out as a fictional piece that tries to tell about the beginnings of my Dalton family. We can never know how far back in time this Dalton line started, but I have started this when the Celtic tribes inhabited Britain many yeas ago. Later on in the narrative, you will read factual information I and other Dalton researchers have found and published with much embellishment. There also is a lot of old English history that I have copied that are in the public domain. From this fictional tale we continue down to a man by the name of le Sieur de Dalton, who is my first documented ancestor, then there is a short history about each successive descendant of my Dalton direct line, with others, down to myself, Garth Rodney Dalton; (my birth name) Most of this later material was copied from my research of my Dalton roots. If you like to read about early British history; Celtic, Romans, Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Knight's, Kings, English, American and family history, then this is the book for you! Some of you will say i am full of it but remember this, “What may have been!” Give it up you knaves! Researched, complied, formated, indexed, wrote, edited, copied, copy-written, misspelled and filed by Rodney G. Dalton in the comfort of his easy chair at 1111 N – 2000 W Farr West, Utah in the United States of America in the Twenty First-Century A.D. -

Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2016 Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England Shawn Hale Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in History at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Hale, Shawn, "Butchered Bones, Carved Stones: Hunting and Social Change in Late Saxon England" (2016). Masters Theses. 2418. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2418 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School� EASTERNILLINOIS UNIVERSITY " Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. • The graduate candidate retains the copyright and intellectual property rights associated with the original research, creative activity, and intellectual or artistic content of the thesis. -

Places to See and Visit

Places to See and Visit When first prepared in 1995 I had prepared these notes for our cottages one mile down the road near Biggin Dale with the intention of providing information regarding local walks and cycle rides but has now expanded into advising as to my personal view of places to observe or visit, most of the places mentioned being within a 25 minutes drive. Just up the road is Heathcote Mere, at which it is well worth stopping briefly as you drive past. Turn right as you come out of the cottage, right up the steep hill, go past the Youth Hostel and it is at the cross-road. In summer people often stop to have picnics here and it is quite colourful in the months of June and July This Mere has existed since at least 1462. For many of the years since 1995, there have been pairs of coots living in the mere's vicinity. If you turn right at the cross roads and Mere, you are heading to Biggin, but after only a few hundred yards where the roads is at its lowest point you pass the entrance gate to the NT nature reserve known as Biggin Dale. On the picture of this dale you will see Cotterill Farm where we lived for 22 years until 2016. The walk through this dale, which is a nature reserve, heads after a 25/30 minute walk to the River Dove (There is also a right turn after 10 minutes to proceed along a bridleway initially – past a wonderful hipped roofed barn, i.e with a roof vaguely pyramid shaped - and then the quietest possible county lane back to Hartington). -

Peveril Castle History Images

HISTORY ALSO AVAILABLE TEACHER’S KIT TO DOWNLOAD PEVERIL CASTLE INFORMATION IMAGES Peveril is a small castle with a substantial but unroofed keep and parts of the curtain wall remaining. Some of the other buildings can be traced in footings. The castle was built on the end of a high ridge, where a gorge cut off the tip and created a separate steep-sided, highly visible and practically impregnable location. HISTORICAL DESCRIPTION Peveril is mentioned in Domesday Book which was The town was established to service the castle. To compiled in 1086. This means that the castle had been provide easier access for the townsfolk and guests, established before this date but after the Norman another entrance was made at the eastern corner. This Conquest of 1066. It was originally granted to William is the point at which the castle is entered today. In the Peveril, one of William 1’s most valued knights, but it 13th-century a larger hall was built and towers were was confiscated from his son later, and throughout its erected on the wall overlooking Cave Dale. history it has periodically reverted to the Crown. It was strategically placed to guard important routeways, and In 1369 the castle came into the hands of John of also to protect the nearby royal hunting forest and rich Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, and passed to his son, Henry lead deposits in the area. 1V. By this time it was obsolete as a fortification or residence, but it continued to be used as the Duchy of The castle was built of stone from the beginning. -

The Hunt in Romance and the Hunt As Romance

THE HUNT IN ROMANCE AND THE HUNT AS ROMANCE A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Jacqueline Stuhmiller May 2005 © 2005 Jacqueline Stuhmiller THE HUNT IN ROMANCE AND THE HUNT AS ROMANCE Jacqueline Stuhmiller, Ph. D. Cornell University 2005 This dissertation examines the English and French late medieval hunting manuals, in particular Gaston Phébus’ Livre de chasse and Edward of Norwich’s Master of Game. It explores their relationships with various literary and nonliterary texts, as well as their roles in the late medieval imagination, aristocratic self-image, and social economy. The medieval aristocracy used hunting as a way to imitate the heroes of chivalric romance, whose main pastimes were courtly love, arms, and the chase. It argues that manuals were, despite appearances, works of popular and imagination-stimulating literature into which moral or practical instruction was incorporated, rather than purely didactic texts. The first three chapters compare the manuals’ content, style, authorial intent, and reader reception with those of the chivalric romances. Both genres are concerned with the interlaced adventures of superlative but generic characters. Furthermore, both genres are popular, insofar as they are written for profit and accessible to sophisticated and unsophisticated readers alike. The following four chapters examine the relationships between hunting, love, and military practices and ethics, as well as those between their respective didactic literatures. Hunters, dogs, and animals occupied a sort of interspecific social hierarchy, and the more noble individuals were expected to adhere to a code of behavior similar to the chivalric code. -

The Viking Winter Camp of 872-873 at Torskey, Lincolnshire

Issue 52 Autumn 2014 ISSN 1740 – 7036 Online access at www.medievalarchaeology.org NEWSLETTER OF THE SOCIETY FOR MEDIEVAL ARCHAEOLOGY Contents Research . 2 Society News . 4 News . 6 Group Reports . 7 New Titles . 10 Media & Exhibitions . 11 Forthcoming Events . 12 The present issue is packed with useful things and readers cannot but share in the keen current interest in matters-Viking. There are some important game-changing publications emerging and in press, as well as exhibitions, to say nothing of the Viking theme that leads the Society's Annual Conference in December. The Group Reports remind members that the medieval world is indeed bigger, while the editor brings us back to earth with some cautious observations about the 'quiet invasion' of Guidelines. Although shorter than usual, we look forward to the next issue being the full 16 pages, when we can expect submissions about current research and discoveries. The Viking winter camp Niall Brady Newsletter Editor of 872-873 at Torskey, e-mail: [email protected] Left: Lincolnshire Geophysical survey at Torksey helps to construct the context for the individual artefacts recovered from the winter camp new archaeological discoveries area. he annual lecture will be delivered this (micel here) spent the winter at Torksey Tyear as part of the Society’s conference, (Lincolnshire). This brief annal tells us which takes place in Rewley House, Oxford little about the events that unfolded, other (5th-7th December) (p. 5 of this newsletter), than revealing that peace was made with and will be delivered by the Society’s the Mercians, and even the precise location Honorary Secretary, Prof. -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31St March 2019

Report and Accounts Year ended 31st March 2019 Preserving the past, investing for the future LLancaster Castle’s John O’Gaunt gate. annual report to 31st March 2019 Annual Report Report and accounts of the Duchy of Lancaster for the year ended 31 March 2019 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838. annual report to 31st March 2019 Introduction Introduction History The Duchy of Lancaster is a private In 1265, King Henry III gifted to his estate in England and Wales second son Edmund (younger owned by Her Majesty The Queen brother of the future Edward I) as Duke of Lancaster. It has been the baronial lands of Simon de the personal estate of the reigning Montfort. A year later, he added Monarch since 1399 and is held the estate of Robert Ferrers, Earl separately from all other Crown of Derby and then the ‘honor, possessions. county, town and castle of Lancaster’, giving Edmund the new This ancient inheritance began title of Earl of Lancaster. over 750 years ago. Historically, Her Majesty The Queen, Duke of its growth was achieved via In 1267, Edmund also received Lancaster. legacy, alliance and forfeiture. In from his father the manor of more modern times, growth and Newcastle-under-Lyme in diversification have been delivered Staffordshire, together with lands through active asset management. and estates in both Yorkshire and Lancashire. This substantial Today, the estate covers 18,481 inheritance was further enhanced hectares of rural land divided into by Edmund’s mother, Eleanor of five Surveys: Cheshire, Lancashire, Provence, who bestowed on him Staffordshire, Southern and the manor of the Savoy in 1284.