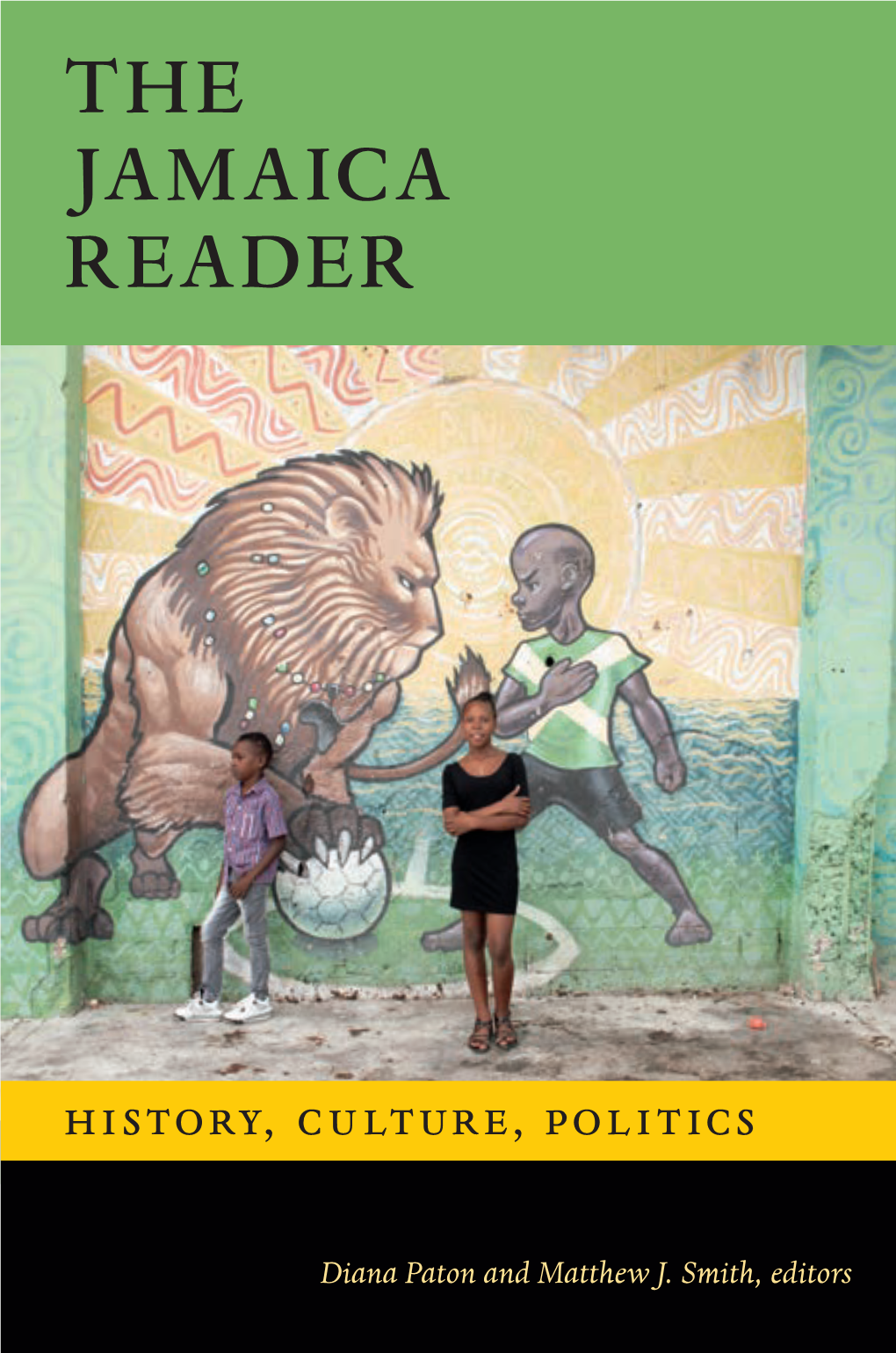

The Jamaica Reader

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean

Integrated Country Strategy Barbados and the Eastern Caribbean FOR PUBLIC RELEASE FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Table of Contents 1. Chief of Mission Priorities ................................................................................................................ 2 2. Mission Strategic Framework .......................................................................................................... 3 3. Mission Goals and Objectives .......................................................................................................... 5 4. Management Objectives ................................................................................................................ 11 FOR PUBLIC RELEASE Approved: August 15, 2018 1 FOR PUBLIC RELEASE 1. Chief of Mission Priorities Our Mission is accredited bilaterally to seven Eastern Caribbean (EC) island nations (Antigua and Barbuda; Barbados; Dominica; Grenada; St. Kitts and Nevis; St. Lucia; and St. Vincent and the Grenadines) and to the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS). All are English- speaking parliamentary democracies with stable political systems. All of the countries are also Small Island Developing States. The U.S. has close ties with these governments. They presently suffer from inherently weak economies, dependent on tourism, serious challenges from transnational crime, and a constant threat from natural disasters. For these reasons, our engagement focuses on these strategic challenges: Safety, Security, and Accountability for American Citizens and Interests Energy -

Downloaded4.0 License

New West Indian Guide 94 (2020) 39–74 nwig brill.com/nwig A Disagreeable Text The Uncovered First Draft of Bryan Edwards’s Preface to The History of the British West Indies, c. 1792 Devin Leigh Department of History, University of California, Davis, Davis, CA, USA [email protected] Abstract Bryan Edwards’s The History of the British West Indies is a text well known to histori- ans of the Caribbean and the early modern Atlantic World. First published in 1793, the work is widely considered to be a classic of British Caribbean literature. This article introduces an unpublished first draft of Edwards’s preface to that work. Housed in the archives of the West India Committee in Westminster, England, this preface has never been published or fully analyzed by scholars in print. It offers valuable insight into the production of West Indian history at the end of the eighteenth century. In particular, it shows how colonial planters confronted the challenges of their day by attempting to wrest the practice of writing West Indian history from their critics in Great Britain. Unlike these metropolitan writers, Edwards had lived in the West Indian colonies for many years. He positioned his personal experience as being a primary source of his historical legitimacy. Keywords Bryan Edwards – West Indian history – eighteenth century – slavery – abolition Bryan Edwards’s The History, Civil and Commercial, of the British Colonies in the West Indies is a text well known to scholars of the Caribbean (Edwards 1793). First published in June of 1793, the text was “among the most widely read and influential accounts of the British Caribbean for generations” (V. -

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States

Historical Origins of the One-Drop Racial Rule in the United States Winthrop D. Jordan1 Edited by Paul Spickard2 Editor’s Note Winthrop Jordan was one of the most honored US historians of the second half of the twentieth century. His subjects were race, gender, sex, slavery, and religion, and he wrote almost exclusively about the early centuries of American history. One of his first published articles, “American Chiaroscuro: The Status and Definition of Mulattoes in the British Colonies” (1962), may be considered an intellectual forerunner of multiracial studies, as it described the high degree of social and sexual mixing that occurred in the early centuries between Africans and Europeans in what later became the United States, and hinted at the subtle racial positionings of mixed people in those years.3 Jordan’s first book, White over Black: American Attitudes Toward the Negro, 1550–1812, was published in 1968 at the height of the Civil Rights Movement era. The product of years of painstaking archival research, attentive to the nuances of the thousands of documents that are its sources, and written in sparkling prose, White over Black showed as no previous book had done the subtle psycho-social origins of the American racial caste system.4 It won the National Book Award, the Ralph Waldo Emerson Prize, the Bancroft Prize, the Parkman Prize, and other honors. It has never been out of print since, and it remains a staple of the graduate school curriculum for American historians and scholars of ethnic studies. In 2005, the eminent public intellectual Gerald Early, at the request of the African American magazine American Legacy, listed what he believed to be the ten most influential books on African American history. -

Branding Jamaica's Tourism Product

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2015 Stepping out from the Crowd: (Re)branding Jamaica's Tourism Product through Sports and Culture Thelca Patrice White Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in Communication Studies at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation White, Thelca Patrice, "Stepping out from the Crowd: (Re)branding Jamaica's Tourism Product through Sports and Culture" (2015). Masters Theses. 2367. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2367 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Graduate School~ U'II'El\.N ILLINOIS UNIVERSITY'" Thesis Maintenance and Reproduction Certificate FOR: Graduate Candidates Completing Theses in Partial Fulfillment of the Degree Graduate Faculty Advisors Directing the Theses RE: Preservation, Reproduction, and Distribution of Thesis Research Preserving, reproducing, and distributing thesis research is an important part of Booth Library's responsibility to provide access to scholarship. In order to further this goal, Booth Library makes all graduate theses completed as part of a degree program at Eastern Illinois University available for personal study, research, and other not-for-profit educational purposes. Under 17 U.S.C. § 108, the library may reproduce and distribute a copy without infringing on copyright; however, professional courtesy dictates that permission be requested from the author before doing so. Your signatures affirm the following: • The graduate candidate is the author of this thesis. -

Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984

University of New Orleans ScholarWorks@UNO University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations Dissertations and Theses 5-18-2007 Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984 Caree Banton University of New Orleans Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td Recommended Citation Banton, Caree, "Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974-1984" (2007). University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations. 508. https://scholarworks.uno.edu/td/508 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by ScholarWorks@UNO with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights- holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in University of New Orleans Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Between Two Giant Sounds: Jamaican Politics, Nationalism, and Musical Culture in Transition, 1974 – 1984 A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the University of New Orleans In partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History By Caree Ann-Marie Banton B.A. Grambling State University 2005 B.P.A Grambling State University 2005 May 2007 Acknowledgement I would like to thank all the people that facilitated the completion of this work. -

Partnership Fact Sheet

PARTNERSHIP FACT SHEET PORTMORE, JAMAICA + TOWNSVILLE, AUSTRALIA LOCATED IN THE ATLANTIC HURRICANE BELT, Portmore, Jamaica is extremely susceptible to hurricanes that RESULTS can cause severe flooding and widespread infrastructure damage. Portmore is a low-lying area on the southern coast of Jamaica. 1 Originally a predominantly agricultural area, the city transformed into a large residential community in the 1950s and became home Based off of a collective social learning for thousands of residents who worked in Kingston. Since then, workshop model from Townsville, the the population of Portmore has grown extremely rapidly, leading partnership hosted a workshop for 46 key it to become the largest residential area in the Caribbean. stakeholders from local government, civil society, and the national government in One of the greatest climate related risks to Portmore is the Portmore to prioritize climate actions that will potential impacts from tropical storms, storm surges and sea feed into Portmore’s Climate Action Plan. level rise. The coastal location of the city also renders it highly susceptible to incremental changes in sea levels and the potential 2 for inundation that will only worsen with future seal level rise. Portmore adopted climate education initiatives from Townsville that will work with students Recognizing that the city’s flood risk is increasing with the threat from elementary to high school on the of climate change, Portmore applied to be part of the CityLinks creation of sensors to monitor indoor energy partnership in the hopes of receiving technical assistance to better consumption and indoor temperatures. plan for future climate impacts. 3 After seeing the impacts white roofs had PARTNERING ON SHARED CLIMATE CHALLENGES in Townsville, Portmore is considering the Although, the distance between Townsville and Portmore design of municipal pilot projects that would couldn’t be greater, local government structure and shared encourage white roofs. -

Book Reviews

African Studies Quarterly | Volume 10, Issue 4 | Spring 2009 BOOK REVIEWS Kwasi Konadu. Indigenous Medicine and Knowledge in African Society. New York: Routledge, 2007. 240p. The historical analysis of conceptions of health and healing in many traditional African societies offer an interesting avenue for the study of the contradictions and ambivalences within definitions of medical knowledge and the concept of disease. Indigenous Medicine and Knowledge in African Society brings to mind the challenges of writing and investigating the therapeutic knowledge of indigenous societies and provides important suggestions for the study of medicine and knowledge systems in Africa. As much about therapeutic knowledge as about culture, it adds to our understanding of the resilience of traditional practices in contemporary Africa. Kwasi Konadu consciously modeled his discussion of traditional Bono-Takyiman (Akan, Ghana) medical knowledge to refute the work of Dennis M. Warren in “Religion, Disease, and Medicine among the Bono-Takyiman,” which relied on the healing knowledge of one traditional healer (Nana Kofi Donkor) as the baseline data in looking at the work of several indigenous healers. Konadu argues that although Warren’s work is laudable, “it must be stated that the experiences, perceptions, and levels of competence amongst healers are not identical, and to use one person as a standard or benchmark seems problematic in the articulation of an ‘ethnomedical system’ authenticated by so few sources that possess equivalent levels of in- depth medical knowledge and aptitude” (xxix). Konadu also hopes for his work to serve as foundation on which future research into indigenous medicine and knowledge would be embedded. -

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari

Negotiating Gender and Spirituality in Literary Representations of Rastafari Annika McPherson Abstract: While the male focus of early literary representations of Rastafari tends to emphasize the movement’s emergence, goals or specific religious practices, more recent depictions of Rasta women in narrative fiction raise important questions not only regarding the discussion of gender relations in Rastafari, but also regarding the functions of literary representations of the movement. This article outlines a dialogical ‘reasoning’ between the different negotiations of gender in novels with Rastafarian protagonists and suggests that the characters’ individual spiritual journeys are key to understanding these negotiations within the gender framework of Rastafarian decolonial practices. Male-centred Literary Representations of Rastafari Since the 1970s, especially, ‘roots’ reggae and ‘dub’ or performance poetry have frequently been discussed as to their relations to the Rastafari movement – not only based on their lyrical content, but often by reference to the artists or poets themselves. Compared to these genres, the representation of Rastafari in narrative fiction has received less attention to date. Furthermore, such references often appear to serve rather descriptive functions, e.g. as to the movement’s philosophy or linguistic practices. The early depiction of Rastafari in Roger Mais’s “morality play” Brother Man (1954), for example, has been noted for its favourable representation of the movement in comparison to the press coverage of -

The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica

timeline The Morant Bay Rebellion in Jamaica Questions A visual exploration of the background to, and events of, this key rebellion by former • What were the causes of the Morant Bay Rebellion? slaves against a colonial authority • How was the rebellion suppressed? • Was it a riot or a rebellion? • What were the consequences of the Morant Bay Rebellion? Attack on the courthouse during the rebellion The initial attack Response from the Jamaican authorities Background to the rebellion Key figures On 11 October 1865, several hundred black people The response of the Jamaican authorities was swift and brutal. Making Like many Jamaicans, both Bogle and Gordon were deeply disappointed about Paul Bogle marched into the town of Morant Bay, the capital of use of the army, Jamaican forces and the Maroons (formerly a community developments since the end of slavery. Although free, Jamaicans were bitter about ■ Leader of the rebellion the mainly sugar-growing parish of St Thomas in the of runaway slaves who were now an irregular but effective army of the the continued political, social and economic domination of the whites. There were ■ A native Baptist preacher East, Jamaica. They pillaged the police station of its colony), the government forcefully put down the rebellion. In the process, also specific problems facing the people: the low wages on the plantations, the ■ Organised the secret meetings weapons and then confronted the volunteer militia nearly 500 people were killed and hundreds of others seriously wounded. lack of access to land for the freed people and the lack of justice in the courts. -

Pas Newsletter W20.Pdf

Program of NEWS AND EVENTS Winter 2020 African Studies Volume 30, Number 2 Message from interim PAS director Wendy Griswold While it has been a challenge Ghana/Africa/World.” The Institute for the Study of Islamic to fill the shoes of departing Thought in Africa (ISITA), which continues to flourish under Program of African Studies director Zekeria Ahmed Salem (political science), brought Susana director Rachel Riedl, we’ve con- Molins-Lliteras (University of Cape Town) to campus to speak tinued to move in the direction on “Iconic Archive: Timbuktu and Its Manuscripts in Public she was heading, even as we set Discourse.” out for some new horizons. At an institution as long established as PAS, now in its 72nd Many PAS activities con- year, much of what takes place is business as usual. Postdocs tinue to be organizaed around and visiting scholars flow through 620 Library Place. Afrisem, three research clusters: Health coordinated by Ahmed Salem and students Patrick Owuor and Healing; Environment, Security, and Development; and Avant- (anthropology) and Omoyemi Aijsebutu (comparative literary Garde Africa. Faculty and students in each cluster pursue indi- studies), carries on as a biweekly venue for presenting disserta- vidual and sometimes collaborative research in the broad areas tion research, and its annual spring conference is in the works. they cover; the clusters also serve as the bases for grant proposals Undergraduates routinely choose from dozens of African studies and other development activities. Each cluster also contributes to electives offered through PAS. Our ties to the Herskovits Library general programming, enabling the various and far-flung mem- and the Block Museum of Art grow ever stronger: Herskovits bers of our community to know what others are doing. -

Em Powering and Engendering Hidden H Istories in Caribbean Peasant Com M Unities

Empowering and Engendering Hidden Histories in Caribbean Peasant Communities Jean Besson (London) Reflecting on the United States South in the 1970s, Eugene Genovese observed that ‘the history of the lower classes has yet to be written’ (1971:102). In the 1980s, the anthropologist Eric Wolf wrote of Eu rope and the People Without History, arguing th at ‘[W]e ... need to un cover the history of “the people without history”- the active histories of “primitives”, peasantries, labourers, immigrants, and besieged minorities’ (1982:v). Keesing likewise noted that Third World peasant communities were still being regarded as ‘more or less closed and self-contained, and often as devoid of known history’ (1981:423). While significant progress in these fields has since been made, academics, journalists and Native Americans all felt it necessary to point to the hidden histories of the post- Columbian Americas in the context of the ‘New World’ quincentenary in 1992 (e.g. Ellwood 1991; Menchú 1992; Besson 1992a, 1992b). This theme was again highlighted in 1994 by the 48th International Congress of Americanists.1 This neglect of ‘the people without history’ has perhaps been nowhere more pronounced than in the Caribbean Region, which has been variously described as the ‘Third World’s third world’ (Naipaul 1973), the ‘oldest colonial sphere’ (Mintz 1971a:17), the ‘gateway to Europe’s New World’ (Besson 1994c), and the ‘core area’ of African America (Mintz 1989:22). Here the Native Americans were virtually wiped out, and post-Conquest societies manufactured through European colonialism, American planta tions, Euro-Asian indenture, and African slavery. In the 1970s and 1980s, Mintz highlighted the neglect, by both anthropologists and historians, of the region’s history and emergent contemporary cultures (1970, 1971b, 1975, 1989). -

The History of St. Ann

The History of St. Ann Location and Geography The parish of St. Ann is is located on the nothern side of the island and is situated to the West of St. Mary, to the east of Trelawny, and is bodered to the south by both St. Catherine and Clarendon. It covers approximately 1,212 km2 and is Jamaica’s largest parish in terms of land mass. St. Ann is known for its red soil, bauxite - a mineral that is considered to be very essential to Jamaica; the mineral is associated with the underlying dry limestone rocks of the parish. A typical feature of St. Ann is its caves and sinkholes such as Green Grotto Caves, Bat Cave, and Dairy Cave, to name a few. The beginning of St. Ann St. Ann was first named Santa Ana (St. Ann) by the Spaniards and because of its natural beauty, it also become known as the “Garden Parish” of Jamaica. The parish’s history runs deep as it is here that on May 4, 1494 while on his second voyage in the Americas, Christopher Columbus first set foot in Jamaica. It is noted that he was so overwhelmed by the attractiveness of the parish that as he pulled into the port at St. Anns Bay, he named the place Santa Gloria. The spot where he disembarked he named Horshoe Bay, primarily because of the shape of the land. As time went by, this name was changed to Dry Harbour and eventually, a more fitting name based on the events that occurred - Discovery Bay.