Antibody Detection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

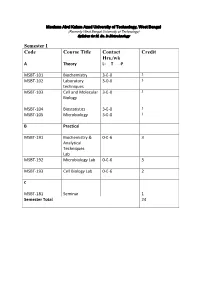

Syllabus for M

Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, West Bengal (Formerly West Bengal University of Technology) Syllabus for M. Sc. In Biotechnology Semester I Code Course Title Contact Credit Hrs./wk A Theory L- T -P MSBT-101 Biochemistry 3-0-0 3 MSBT-102 Laboratory 3-0-0 3 techniques MSBT-103 Cell and Molecular 3-0-0 3 Biology MSBT-104 Biostatistics 3-0-0 3 MSBT-105 Microbiology 3-0-0 3 B Practical MSBT-191 Biochemistry & 0-0-6 3 Analytical Techniques Lab MSBT-192 Microbiology Lab 0-0-6 3 MSBT-193 Cell Biology Lab 0-0-6 2 C MSBT-181 Seminar 1 Semester Total 24 Maulana Abul Kalam Azad University of Technology, West Bengal (Formerly West Bengal University of Technology) Syllabus for M. Sc. In Biotechnology MSBT101: Biochemistry credits 3 Unit 1: Basic chemistry for biologists Formation of chemical bonds, molecular orbital (MO) theory and linear combination of atomic orbitals (LCAO),basics of mass spectrometry, molecules, Avogadro number, molarity, chemical reactions, reaction stoichiometry, rates of reaction, rate constants, order of reactions,kinetic versus thermodynamic controls of a reaction, reaction equilibrium (equilibrium constant); light and matter interactions (optical spectroscopy, fluorescence, bioluminescence, paramagnetism and diamagnetism, photoelectron spectroscopy; chemical bonds (ionic, covalent, Van derWalls forces); electronegativity, polarity; VSEPR theory and molecular geometry, dipole moment, orbital hybridizations; acids, bases and pH - Arrhenious theory, pH, ionic product of water, weak acids and bases, conjugate acid-base pairs, buffers and buffering action etc; chemical thermodynamics - internal energy, heat and temperature, enthalpy (bond enthalpy and reaction enthalpy), entropy, Gibbs free energy of ATP driven reactions, spontaneity versus driven reactions in biology;bond rotations and molecular conformations - Newman projections, conformational analysis of alkanes, alkenes and alkynes; functional groups, optically asymmetric carbon centers, amino acids, proteins, rotational freedoms in polypeptide backbone (Ramachandran plot). -

A Conserved Influenza a Virus Nucleoprotein Code Controls Specific

ARTICLE Received 8 Mar 2016 | Accepted 10 Aug 2016 | Published 21 Sep 2016 DOI: 10.1038/ncomms12861 OPEN A conserved influenza A virus nucleoprotein code controls specific viral genome packaging E´tori Aguiar Moreira1,2,3, Anna Weber1, Hardin Bolte1,2,3, Larissa Kolesnikova4, Sebastian Giese1, Seema Lakdawala5, Martin Beer6, Gert Zimmer7, Adolfo Garcı´a-Sastre8,9,10, Martin Schwemmle1 & Mindaugas Juozapaitis1 Packaging of the eight genomic RNA segments of influenza A viruses (IAV) into viral particles is coordinated by segment-specific packaging sequences. How the packaging signals regulate the specific incorporation of each RNA segment into virions and whether other viral or host factors are involved in this process is unknown. Here, we show that distinct amino acids of the viral nucleoprotein (NP) are required for packaging of specific RNA segments. This was determined by studying the NP of a bat influenza A-like virus, HL17NL10, in the context of a conventional IAV (SC35M). Replacement of conserved SC35M NP residues by those of HL17NL10 NP resulted in RNA packaging defective IAV. Surprisingly, substitution of these conserved SC35M amino acids with HL17NL10 NP residues led to IAV with altered packaging efficiencies for specific subsets of RNA segments. This suggests that NP harbours an amino acid code that dictates genome packaging into infectious virions. 1 Institute of Virology, University Medical Center Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany. 2 Spemann Graduate School of Biology and Medicine, University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany. 3 Faculty of Biology, University of Freiburg, 79104 Freiburg, Germany. 4 Institute of Virology, Philipps-Universita¨t Marburg, 35043 Marburg, Germany. 5 Department of Microbiology and Molecular Genetics, University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15217, USA. -

Technical Methods

J Clin Pathol 1987;40:581-588 J Clin Pathol: first published as 10.1136/jcp.40.5.581 on 1 May 1987. Downloaded from 56°C for 30 minutes. Technical methods Complement fixation tests were performed accord- ing to established methods,10 1 except that microtitre plates were used instead of World Health Organisation trays. For maximum sensitivity an ini- Cytomegalovirus (CMV) tial serum dilution of 1/4 was used. The antigen prep- antibody screening in blood aration used was a CMV complement fixation test antigen supplied by either Flow Laboratories Ltd, donors: modification of new latex Irvine, Scotland, or the Central Public Health Labo- ratory, Colindale, England. Guinea pig complements agglutination test compared with were supplied by Wellcome Diagnostics, Dartford, two standard methods England, or Don Whitly Scientific Ltd, Shipley, England. Complement fixation tests were performed A PUCKETT J E DAVIS From the Regional Blood using the following CMV antigen and complement Transfusion Centre, John Radeliffe Hospital, combinations: (1) PHLS CMV antigen + Wellcome Headington, Oxford, England Diagnostics complement, (2) PHLS CMV antigen + Don Whitly complement, and (3) Flow Laboratories CMV antigen + Wellcome Diagnostics complement. Infection with cytomegalovirus (CMV) is common, Immunofluorescence tests were performed and between 50 and 100% of adults may show evi- according to a standard method12 13 using substrate dence of infection.1 The transmission of the virus by slides of CMV infected (Westwood strain) fibroblasts blood transfusion2 and, therefore, the need to screen the Oxford Public Health Laboratory. donations intended for at risk groups such as provided by immunocompromised patients34 and neonates5 -7 iS CMV Scan passive latex agglutination kits were now well established. -

Dissecting Human Antibody Responses Against Influenza a Viruses and Antigenic Changes That Facilitate Immune Escape

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2018 Dissecting Human Antibody Responses Against Influenza A Viruses And Antigenic Changes That Facilitate Immune Escape Seth J. Zost University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Allergy and Immunology Commons, Immunology and Infectious Disease Commons, Medical Immunology Commons, and the Virology Commons Recommended Citation Zost, Seth J., "Dissecting Human Antibody Responses Against Influenza A Viruses And Antigenic Changes That Facilitate Immune Escape" (2018). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 3211. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3211 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/3211 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dissecting Human Antibody Responses Against Influenza A Viruses And Antigenic Changes That Facilitate Immune Escape Abstract Influenza A viruses pose a serious threat to public health, and seasonal circulation of influenza viruses causes substantial morbidity and mortality. Influenza viruses continuously acquire substitutions in the surface glycoproteins hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA). These substitutions prevent the binding of pre-existing antibodies, allowing the virus to escape population immunity in a process known as antigenic drift. Due to antigenic drift, individuals can be repeatedly infected by antigenically distinct influenza strains over the course of their life. Antigenic drift undermines the effectiveness of our seasonal influenza accinesv and our vaccine strains must be updated on an annual basis due to antigenic changes. In order to understand antigenic drift it is essential to know the sites of antibody binding as well as the substitutions that facilitate viral escape from immunity. -

Safety and Immunogenicity of a Baculovirus- Expressed Hemagglutinin Influenza Vaccine a Randomized Controlled Trial

PRELIMINARY COMMUNICATION Safety and Immunogenicity of a Baculovirus- Expressed Hemagglutinin Influenza Vaccine A Randomized Controlled Trial John J. Treanor, MD Context A high priority in vaccine research is the development of influenza vaccines Gilbert M. Schiff, MD that do not use embryonated eggs as the substrate for vaccine production. Frederick G. Hayden, MD Objective To determine the dose-related safety, immunogenicity, and protective ef- ficacy of an experimental trivalent influenza virus hemagglutinin (rHA0) vaccine pro- Rebecca C. Brady, MD duced in insect cells using recombinant baculoviruses. C. Mhorag Hay, MD Design, Setting, and Participants Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled Anthony L. Meyer, BS clinical trial at 3 US academic medical centers during the 2004-2005 influenza season Jeanne Holden-Wiltse, MPH among 460 healthy adults without high-risk indications for influenza vaccine. Hua Liang, PhD Interventions Participants were randomly assigned to receive a single injection of saline placebo (n=154); 75 µg of an rHA0 vaccine containing 15 µg of hemagglutinin Adam Gilbert, PhD from influenza A/New Caledonia/20/99(H1N1) and influenza B/Jiangsu/10/03 virus Manon Cox, PhD and 45 µg of hemagglutinin from influenza A/Wyoming/3/03(H3N2) virus (n=153); or 135 µg of rHA0 containing 45 µg of hemagglutinin each from all 3 components LL CURRENTLY LICENSED IN- (n=153). Serum samples were taken before and 30 days following immunization. fluenza vaccines in the United Main Outcome Measures Primary safety end points were the rates and severity of States are produced in em- solicited and unsolicited adverse events. Primary immunogenicity end points were the bryonated hen’s eggs. -

Biosafety Recommendations for Work with Influenza Viruses Containing a Hemagglutinin from the A/Goose/Guangdong/1/96 Lineage

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report Recommendations and Reports / Vol. 62 / No. 6 June 28, 2013 Biosafety Recommendations for Work with Influenza Viruses Containing a Hemagglutinin from the A/goose/Guangdong/1/96 Lineage U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Recommendations and Reports CONTENTS Introduction ............................................................................................................2 Background .............................................................................................................2 Guidelines for Working with Influenza Viruses Containing an HA from the A/goose/Guangdong/1/96 Lineage ..................................3 Conclusion ...............................................................................................................6 References ...............................................................................................................7 Front cover photo: Transmission electron micrograph of avian influenza A H5N1 viruses (gold) grown in Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells (green). The MMWR series of publications is published by the Office of Surveillance, Epidemiology, and Laboratory Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Atlanta, GA 30333. Suggested Citation: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Title]. MMWR 2013;62(No. RR-#):[inclusive page numbers]. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Thomas R. Frieden, MD, MPH, Director -

Autocatalytic Activation of Influenza Hemagglutinin

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of Chemical & Biomolecular Departmental Papers (CBE) Engineering December 2006 Autocatalytic Activation of Influenza Hemagglutinin Jeong H. Lee University of Pennsylvania Mark Goulian University of Pennsylvania Eric T. Boder University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/cbe_papers Recommended Citation Lee, J. H., Goulian, M., & Boder, E. T. (2006). Autocatalytic Activation of Influenza Hemagglutinin. Retrieved from https://repository.upenn.edu/cbe_papers/83 Postprint version. Published in Journal of Molecular Biology, Volume 364, Issue 3, December 2006, pages 275-282. Publisher URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmb.2006.09.015 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/cbe_papers/83 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Autocatalytic Activation of Influenza Hemagglutinin Abstract Enveloped viruses contain surface proteins that mediate fusion between the viral and target cell membranes following an activating stimulus. Acidic pH induces the influenza virus fusion protein hemagglutinin (HA) via irreversible refolding of a trimeric conformational state leading to exposure of hydrophobic fusion peptides on each trimer subunit. Herein, we show that cells expressing fowl plague virus HA demonstrate discrete switching behavior with respect to the HA conformational change. Partially activated states do not exist at the scale of the cell, activation of HA leads to aggregation of cell surface trimers, and newly synthesized HA refold spontaneously in the presence of previously activated HA. These observations imply a feedback mechanism involving self-catalyzed refolding of HA and thus suggest a mechanism similar to the autocatalytic refolding and aggregation of prions. -

Serological Methods in the Identification and Characterization of Viruses

CHAPTER 4 Serological Methods in the Identification and Characterization of Viruses M. H. V. Van Regenmortel Laboratoire de Virologie Institut de Biologie Mo!eculaire et Cellulaire 67000 Strasbourg, France 1. INTRODUCTION The purpose of this chapter is to present an integrated view of the various serological techniques that have been used in virology. The accent will be placed on the principles that govern each type of test and on the general applicability of the different serological techniques in all fields of virus research. In recent years, advances in serological tech niques have sometimes been applied in only one area of virology, although they could have been equally useful to workers studying other groups of viruses. No doubt this stems from the host-oriented approach that has guided the compartmentation of virology into separate fields of specialization. When it comes to serological properties, however, the similarities between animal, insect, bacterial, and plant viruses are paramount. The same immunochemical principles govern the in vitro serological reactions of all viral antigens, and much of general interest can be learned from the findings obtained with each particular group of viruses. An attempt will be made here to emphasize the general validity of specific experimental procedures. A number of recent reviews restricted to the serology of particular groups of viruses are available 183 H. Fraenkel-Conrat et al. (eds.), Comprehensive Virology © Plenum Press, New York 1981 184 Chapter 4 (Cowan, 1973; Schmidt and Lennette, 1973; Ball, 1974; Kurstak and Morisset, 1974; Burns and Allison, 1975; Mazzone and Tignor, 1976; Mayr et al., 1977; Tyrrell, 1978; Van Regenmortel, 1978; Cooper, 1979). -

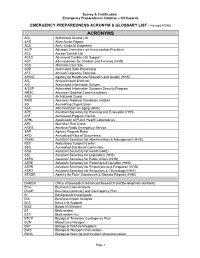

ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008

Survey & Certification Emergency Preparedness Initiative – All Hazards EMERGENCY PREPAREDNESS ACRONYM & GLOSSARY LIST - Revised 9/2008 ACRONYMS AAL Authorized Access List AAR After-Action Report ACE Army Corps of Engineers ACIP Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices ACL Access Control List ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support ACF Administration for Children and Families (HHS) ACS Alternate Care Site ADP Automated Data Processing AFE Annual Frequency Estimate AHRQ Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (HHS) AIE Annual Impact Estimate AIS Automated Information System AISSP Automated Information Systems Security Program AMSC American Satellite Communications ANG Air National Guard ANSI American National Standards Institute AO Accrediting Organization AoA Administration on Aging (HHS) APE Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (HHS) APF Authorized Program Facility APHL Association of Public Health Laboratories ARC American Red Cross ARES Amateur Radio Emergency Service ARF Agency Request Form ARO Annualized Rate of Occurrence ASAM Assistant Secretary for Administration & Management (HHS) ASC Ambulatory Surgical Center ASC Accredited Standards Committee ASH Assistant Secretary for Health (HHS) ASL Assistant Secretary for Legislation (HHS) ASPA Assistant Secretary for Public Affairs (HHS) ASPE Assistant Secretary for Planning & Evaluation (HHS) ASPR Assistant Secretary for Preparedness & Response (HHS) ASRT Assistant Secretary for Resources & Technology (HHS) ATSDR Agency for Toxic Substances & Disease Registry (HHS) BARDA -

Msc Biochemistry Autonomy 2015-17

Bhavan’s Vivekananda College of Science, Humanities and Commerce, Sainikpuri, Secunderabad–500094 Autonomous (Accredited with ‘A’ grade by NAAC) MSc Biochemistry Autonomy 2015-17 Bhavan’s Vivekananda College of Science, Humanities and Commerce, Sainikpuri, Secunderabad–500094 Autonomous (Accredited with ‘A’ grade by NAAC) M.Sc. Biochemistry Syllabus (Effective from 2015 admitted batch) SEMESTER I PAPERS TITLE Teaching Credits Internal Final hrs/week marks exam marks 1 Paper-I : BI101T:Chemistry and Metabolism of Proteins, Lipids and Porphyrins 4 4 30 70 2 Paper-II : BI102T:Chemistry and Metabolism of Carbohydrates, Vitamins 4 4 30 70 and Nucleic Acids 3 Paper-III: BI 103T: Bio-Analytical Techniques 4 4 30 70 4 Paper-IV: BI104T:BioenergeticsAndCellBiology 4 4 30 70 5 Paper-V: BI105P: Amino acids and protein analysis 8 4 -- 100 6 Paper-VI: BI106P: Carbohydrate and lipid analysis 8 4 -- 100 Total 32 24 120 480 SEMESTER II PAPERS TITLE Teaching Credits Internal Final hrs/week marks exam marks 1 Paper-I:BI201T:Enzymology 4 4 30 70 2 Paper-II:BI202T:MolecularBiology 4 4 30 70 3 Paper-III:BI203T:BiochemicalGeneticsAndModelOrganisms 4 4 30 70 4 Paper-IV: B1 204T: Computational methods and Cell study methods 4 4 30 70 5 Paper-V:BI205P:Enzymology and Biochemical preparations 8 4 -- 100 6 Paper-VI:BI206P: Molecular Biology, Genetics and Quantitative Biology 8 4 -- 100 Total 32 24 120 480 SEMESTER III PAPERS TITLE Teaching Credits Internal Final hrs/week marks exam marks 1 Paper-I:BI301T:GeneRegulation and Genetic Engineering 4 4 30 70 2 Paper-II:BI302T:Immunology and Immunotechnology 4 4 30 70 3 Paper-III:BI303T: Virology, Nutrition & Clinical Biochemistry. -

Virology Techniques

Chapter 5 - Lesson 4 Virology Techniques Introduction Virology is a field within microbiology that encom- passes the study of viruses and the diseases they cause. In the laboratory, viruses have served as useful tools to better understand cellular mechanisms. The purpose of this lesson is to provide a general overview of laboratory techniques used in the identification and study of viruses. A Brief History In the late 19th century the independent work of Dimitri Ivanofsky and Martinus Beijerinck marked the begin- This electron micrograph depicts an influenza virus ning of the field of virology. They showed that the agent particle or virion. CDC. responsible for causing a serious disease in tobacco plants, tobacco mosaic virus, was able to pass through filters known to retain bacteria and the filtrate was able to cause disease in new plants. In 1898, Friedrich Loef- fler and Paul Frosch applied the filtration criteria to a disease in cattle known as foot and mouth disease. The filtration criteria remained the standard method used to classify an agent as a virus for nearly 40 years until chemical and physical studies revealed the structural basis of viruses. These attributes have become the ba- sis of many techniques used in the field today. Background All organisms are affected by viruses because viruses are capable of infecting and causing disease in all liv- ing species. Viruses affect plants, humans, and ani- mals as well as bacteria. A virus that infects bacteria is known as a bacteriophage and is considered the Bacteriophage. CDC. Chapter 5 - Human Health: Real Life Example (Influenza) 1 most abundant biological entity on the planet. -

Influenza Virus Hemagglutinin Stalk-Based Antibodies and Vaccines

Available online at www.sciencedirect.com Influenza virus hemagglutinin stalk-based antibodies and vaccines 1 1,2 Florian Krammer and Peter Palese Antibodies against the conserved stalk domain of the activity and can readily be measured in serum using the hemagglutinin are currently being discussed as promising hemagglutination inhibition (HI) assay [3]. These anti- therapeutic tools against influenza virus infections. Because of bodies are directed against the membrane distal part of the the conservation of the stalk domain these antibodies are able to HA, the globular head domain (Figure 1a,b,d) [4,5,6 ], broadly neutralize a wide spectrum of influenza virus strains and which has a high plasticity and is subject to constant subtypes. Broadly protective vaccine candidates based on the antigenic drift driven by human herd immunity. There- epitopes of these antibodies, for example, chimeric and headless fore, antibodies that target this domain (HI-active anti- hemagglutinin structures, are currently under development and bodies) are very strain specific and quickly lose efficacy show promising results in animals models. These candidates against drifted strains. Because of this viral mechanism to could be developed into universal influenza virus vaccines that escape human herd immunity influenza virus vaccines protect from infection with drifted seasonal as well as novel have to be reformulated almost annually based on surveil- pandemic influenza virus strains therefore obviating the need for lance data from laboratories in the Northern and Southern annual vaccination, and enhancing our pandemic preparedness. hemispheres [7]. Vaccine strain prediction based on sur- Addresses veillance is a complicated and error prone process and 1 Department of Microbiology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, produces mismatches between circulating virus and New York, NY, USA vaccine strains from time to time which leads to a severe 2 Department of Medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, drop in efficacy of the seasonal influenza virus vaccines [8– New York, NY, USA 12].