8. “A Man of Great Energy and Ambition”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Socio-Cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women's

A Socio-cultural Investigation of Indigenous Fijian Women’s Perception of and Responses to HIV and AIDS from the Two Selected Tribes in Rural Fiji Tabalesi na Dakua,Ukuwale na Salato Ms Litiana N. Tuilaselase Kuridrani MBA; PG Dip Social Policy Admin; PG Dip HRM; Post Basic Public Health; BA Management/Sociology (double major); FRNOB A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2013 School of Population Health Abstract This thesis reports the findings of the first in-depth qualitative research on the socio-cultural perceptions of and responses to HIV and AIDS from the two selected tribes in rural Fiji. The study is guided by an ethnographic framework with grounded theory approach. Data was obtained using methods of Key Informants Interviews (KII), Focus Group Discussions (FGD), participant observations and documentary analysis of scripts, brochures, curriculum, magazines, newspapers articles obtained from a broad range of Fijian sources. The study findings confirmed that the Indigenous Fijian women population are aware of and concerned about HIV and AIDS. Specifically, control over their lives and decision-making is shaped by changes of vanua (land and its people), lotu (church), and matanitu (state or government) structures. This increases their vulnerabilities. Informants identified HIV and AIDS with a loss of control over the traditional way of life, over family ties, over oneself and loss of control over risks and vulnerability factors. The understanding of HIV and AIDS is situated in the cultural context as indigenous in its origin and required a traditional approach to management and healing. -

Central Division

THE FOLLOWING IS THE PROVISIONAL LIST OF POLLING VENUES AS AT 3IST DECEMBER 2017 CENTRAL DIVISION The following is a Provisional List of Polling Venues released by the Fijian Elections Office FEO[ ] for your information. Members of the public are advised to log on to pvl.feo.org.fj to search for their polling venues by district, area and division. DIVISION: CENTRAL AREA: VUNIDAWA PRE POLL VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA Voter No Venue Name Venue Address Count Botenaulu Village, Muaira, 1 Botenaulu Community Hall 78 Naitasiri Delailasakau Community Delailasakau Village, Nawaidi- 2 107 Hall na, Naitasiri Korovou Community Hall Korovou Village, Noimalu , 3 147 Naitasiri Naitasiri Laselevu Village, Nagonenicolo 4 Laselevu Community Hall 174 , Naitasiri Lomai Community Hall Lomai Village, Nawaidina, 5 172 Waidina Naitasiri 6 Lutu Village Hall Wainimala Lutu Village, Muaira, Naitasiri 123 Matainasau Village Commu- Matainasau Village, Muaira , 7 133 nity Hall Naitasiri Matawailevu Community Matawailevu Village, Noimalu , 8 74 Hall Naitasiri Naitasiri Nabukaluka Village, Nawaidina ELECTION DAY VENUES -AREA VUNIDAWA 9 Nabukaluka Community Hall 371 , Naitasiri Nadakuni Village, Nawaidina , Voter 10 Nadakuni Community Hall 209 No Venue Name Venue Address Naitasiri Count Nadovu Village, Muaira , Nai- Bureni Settlement, Waibau , 11 Nadovu Community Hall 160 1 Bureni Community Hall 83 tasiri Naitasiri Naitauvoli Village, Nadara- Delaitoga Village, Matailobau , 12 Naitauvoli Community Hall 95 2 Delaitoga Community Hall 70 vakawalu , Naitasiri Naitasiri Nakida -

The Case for Lau and Namosi Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali

ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI MASILINA TUILOA ROTUIVAQALI ACCOUNTABILITY IN FIJI’S PROVINCIAL COUNCILS AND COMPANIES: THE CASE FOR LAU AND NAMOSI by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Commerce Copyright © 2012 by Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali School of Accounting & Finance Faculty of Business & Economics The University of the South Pacific September, 2012 DECLARATION Statement by Author I, Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali, declare that this thesis is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published, or substantially overlapping with material submitted for the award of any other degree at any institution, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Signature………………………………. Date……………………………… Name: Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali Student ID No: S00001259 Statement by Supervisor The research in this thesis was performed under my supervision and to my knowledge is the sole work of Mrs. Masilina Tuiloa Rotuivaqali. Signature……………………………… Date………………………………... Name: Michael Millin White Designation: Professor in Accounting DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my beloved daughters Adi Filomena Rotuisolia, Adi Fulori Rotuisolia and Adi Losalini Rotuisolia and to my niece and nephew, Masilina Tehila Tuiloa and Malakai Ebenezer Tuiloa. I hope this thesis will instill in them the desire to continue pursuing their education. As Nelson Mandela once said and I quote “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT The completion of this thesis owes so much from the support of several people and organisations. -

We Are Kai Tonga”

5. “We are Kai Tonga” The islands of Moala, Totoya and Matuku, collectively known as the Yasayasa Moala, lie between 100 and 130 kilometres south-east of Viti Levu and approximately the same distance south-west of Lakeba. While, during the nineteenth century, the three islands owed some allegiance to Bau, there existed also several family connections with Lakeba. The most prominent of the few practising Christians there was Donumailulu, or Donu who, after lotuing while living on Lakeba, brought the faith to Moala when he returned there in 1852.1 Because of his conversion, Donu was soon forced to leave the island’s principal village, Navucunimasi, now known as Naroi. He took refuge in the village of Vunuku where, with the aid of a Tongan teacher, he introduced Christianity.2 Donu’s home island and its two nearest neighbours were to be the scene of Ma`afu’s first military adventures, ostensibly undertaken in the cause of the lotu. Richard Lyth, still working on Lakeba, paid a pastoral visit to the Yasayasa Moala in October 1852. Despite the precarious state of Christianity on Moala itself, Lyth departed in optimistic mood, largely because of his confidence in Donu, “a very steady consistent man”.3 He observed that two young Moalan chiefs “who really ruled the land, remained determined haters of the truth”.4 On Matuku, which he also visited, all villages had accepted the lotu except the principal one, Dawaleka, to which Tui Nayau was vasu.5 The missionary’s qualified optimism was shattered in November when news reached Lakeba of an attack on Vunuku by the two chiefs opposed to the lotu. -

Severe Tc Gita (Cat4) Passes Just South of Ono

FIJI METEOROLOGICAL SERVICES GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI MEDIA RELEASE No.35 5pm, Tuesday 13 February 2018 SEVERE TC GITA (CAT4) PASSES JUST SOUTH OF ONO Severe TC Gita (Category 4) entered Fiji Waters this morning and passed just south of Ono-i- lau at around 1.30pm this afternoon. Hurricane force winds of 68 knots and maximum momentary gusts of 84 knots were recorded at Ono-i-lau at 2pm this afternoon as TC Gita tracked westward. Vanuabalavu also recorded strong and gusty winds (Table 1). Severe “TC Gita” was located near 21.2 degrees south latitude and 178.9 degrees west longitude or about 60km south-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 390km southeast of Kadavu at 3pm this afternoon. It continues to move westward at about 25km/hr and expected to continue on this track and gradually turn west-southwest. On its projected path, Severe TC Gita is predicted to be located about 140km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau or 300km southeast of Kadavu around 8pm tonight. By 2am tomorrow morning, Severe TC Gita is expected to be located about 240km west-southwest of Ono-i-lau and 250km southeast of Kadavu and the following warnings remains in force: A “Hurricane Warning” remains in force for Ono-i-lau and Vatoa; A “Storm Warning” remains in force for the rest of Southern Lau group; A “Gale Warning” remains in force for Matuku, Totoya, Moala , Kadavu and nearby smaller islands and is now in force for Lakeba and Nayau; A “Strong Wind Warning” remains in force for Central Lau Group, Lomaiviti Group, southern half of Viti Levu and is now in force for rest of Fiji. -

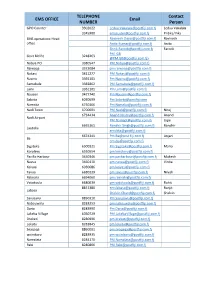

EMS Operations Centre

TELEPHONE Contact EMS OFFICE Email NUMBER Person GPO Counter 3302022 [email protected] Ledua Vakalala 3345900 [email protected] Pritika/Vika EMS operations-Head [email protected] Ravinesh office [email protected] Anita [email protected] Farook PM GB Govt Bld Po 3218263 @[email protected]> Nabua PO 3380547 [email protected] Raiwaqa 3373084 [email protected] Nakasi 3411277 [email protected] Nasinu 3392101 [email protected] Samabula 3382862 [email protected] Lami 3361101 [email protected] Nausori 3477740 [email protected] Sabeto 6030699 [email protected] Namaka 6750166 [email protected] Nadi Town 6700001 [email protected] Niraj 6724434 [email protected] Anand Nadi Airport [email protected] Jope 6665161 [email protected] Randhir Lautoka [email protected] 6674341 [email protected] Anjani Ba [email protected] Sigatoka 6500321 [email protected] Maria Korolevu 6530554 [email protected] Pacific Harbour 3450346 [email protected] Mukesh Navua 3460110 [email protected] Vinita Keiyasi 6030686 [email protected] Tavua 6680239 [email protected] Nilesh Rakiraki 6694060 [email protected] Vatukoula 6680639 [email protected] Rohit 8812380 [email protected] Ranjit Labasa [email protected] Shalvin Savusavu 8850310 [email protected] Nabouwalu 8283253 [email protected] -

Tuesday-27Th November 2018

PARLIAMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF FIJI PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DAILY HANSARD TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 [CORRECTED COPY] C O N T E N T S Pages Minutes … … … … … … … … … … 10 Communications from the Chair … … … … … … … 10-11 Point of Order … … … … … … … … … … 11-12 Debate on His Excellency the President’s Address … … … … … 12-68 List of Speakers 1. Hon. J.V. Bainimarama Pages 12-17 2. Hon. S. Adimaitoga Pages 18-20 3. Hon. R.S. Akbar Pages 20-24 4. Hon. P.K. Bala Pages 25-28 5. Hon. V.K. Bhatnagar Pages 28-32 6. Hon. M. Bulanauca Pages 33-39 7. Hon. M.D. Bulitavu Pages 39-44 8. Hon. V.R. Gavoka Pages 44-48 9. Hon. Dr. S.R. Govind Pages 50-54 10. Hon. A. Jale Pages 54-57 11. Hon. Ro T.V. Kepa Pages 57-63 12. Hon. S.S. Kirpal Pages 63-64 13. Hon. Cdr. S.T. Koroilavesau Pages 64-68 Speaker’s Ruling … … … … … … … … … 68 TUESDAY, 27TH NOVEMBER, 2018 The Parliament resumed at 9.36 a.m., pursuant to adjournment. HONOURABLE SPEAKER took the Chair and read the Prayer. PRESENT All Honourable Members were present. MINUTES HON. LEADER OF THE GOVERNMENT IN PARLIAMENT.- Madam Speaker, I move: That the Minutes of the sittings of Parliament held on Monday, 26th November 2018, as previously circulated, be taken as read and be confirmed. HON. A.A. MAHARAJ.- Madam Speaker, I beg to second the motion. Question put Motion agreed to. COMMUNICATIONS FROM THE CHAIR Welcome I welcome all Honourable Members to the second sitting day of Parliament for the 2018 to 2019 session. -

The Diversity of Fijian Polities

7 The Diversity of Fijian Polities An overall discussion of the general diversity of traditional pan-Fijian polities immediately prior to Cession in 1874 will set a wider perspective for the results of my own explorations into the origins, development, structure and leadership of the yavusa in my three field areas, and the identification of different patterning of interrelationships between yavusa. The diversity of pan-Fijian polities can be most usefully considered as a continuum from the simplest to the most complex levels of structured types of polity, with a tentative geographical distribution from simple in the west to extremely complex in the east. Obviously I am by no means the first to draw attention to the diversity of these polities and to point out that there are considerable differences in the principles of structure, ranking and leadership between the yavusa and the vanua which I have investigated and those accepted by the government as the model. G.K. Roth (1953:58–61), not unexpectedly as Deputy Secretary of Fijian Affairs under Ratu Sir Lala Sukuna, tended to accord with the public views of his mentor; although he did point out that ‘The number of communities found in a federation was not the same in all parts of Fiji’. Rusiate Nayacakalou who carried out his research in 1954, observed (1978: xi) that ‘there are some variations in the traditional structure from one village to another’. Ratu Sukuna died in 1958, and it may be coincidental that thereafter researchers paid more emphasis to the differences I referred to. Isireli Lasaqa who was Secretary to Cabinet and Fijian Affairs was primarily concerned with political and other changes in the years before and after independence in 1970. -

Researchspace@Auckland

http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz ResearchSpace@Auckland Copyright Statement The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). This thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: • Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. • Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author's right to be identified as the author of this thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. • You will obtain the author's permission before publishing any material from their thesis. To request permissions please use the Feedback form on our webpage. http://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/feedback General copyright and disclaimer In addition to the above conditions, authors give their consent for the digital copy of their work to be used subject to the conditions specified on the Library Thesis Consent Form and Deposit Licence. CONNECTING IDENTITIES AND RELATIONSHIPS THROUGH INDIGENOUS EPISTEMOLOGY: THE SOLOMONI OF FIJI ESETA MATEIVITI-TULAVU A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY The University of Auckland Auckland, New Zealand 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract .................................................................................................................................. vi Dedication ............................................................................................................................ -

Wansolwara, September 2011, 16(2)

Volume 16, No. 2 SEPTEMBER, 2011 Wansolwara An independent student newspaper and online publication Youth fund Report moots regional initiative to resolve lack of progress with the opportunities to associations to address the to the formal curriculum and by PARIJATA GURDAYAL propose projects that have a various youth issues. involve working closely with THERE is a need for a regional strong community focus. “Specifi c projects could be partners in the community, youth fund to provide youths “The absence of available funded to improve female and such as local government and with the needed resources to resources is a major reason male access to higher levels of church groups, it noted. INSIGHT address their issues. for the lack of progress at the education or basic literacy, or An alternative was for the This was one of the recom- regional country level in ad- providing more educational projects to be proposed and FORESTS are vital for the mendations in the State of Pa- dressing youth issues,” it said. or livelihood opportunities run by youth-led associations security of Pacifi c Island cifi c Youth 2011: Opportuni- The report proposes a for young people with HIV & that involve school leavers. ties and Obstacles report that system for addressing this gap AIDS, or physical or mental “The creation of links be- nations. Is enough being was released by the Secretar- through a regional agency such disabilities,” it said. tween communities should be iat of the Pacifi c Community as the SPC to set up a regional To attain a stronger commu- an important focus to lift the done to protect it? (SPC) and the United Nations youth challenge fund. -

FEMIS ECE Contact List- 2020

FEMIS ECE Contact List- 2020 School Code School Name District Telephone Email Location Mailing Address 8759 Abaca Early Learning Lautoka- Abaca PO Box 6729, Kindergarten Yasawa Village, Lautoka Lautoka 9762 Abc Kindergarten Nadroga- 4503979 [email protected] Tau Fijian P O Box 2164, Nadi, Navosa School Compound 8416 Adi Maopa Eastern 3545234 [email protected] Lomaloma P O Lomaloma Kindergarten Vanuabalavu 8138 Agape Kindergarten Lautoka- Lautoka Yasawa 9934 Aman's Memorial Suva 8725963 23 Borete P O Box 8118, Kindergarten Rd. , Valelevu, Nadawa, nasinu 8736 Amazing Grace Suva 8667295 [email protected] Lot 13 Stage P O Box 18337 Suva Kindergarten Sakoca II Sakoca Sub-division Tamavua 8190 American International Lautoka- 6724949 [email protected] Nadi Back P O Box 9857 Nadi christian School Yasawa Road Airport Fiji Kindergarten 9606 Amichandra Lautoka- 4502415 [email protected] Lautoka City C/- P O Box 562, Kindergarten Yasawa Lautoka, 9972 Anand Kindergarten Nadroga- 706555 Nalovo, Nadi P O Box 1853, Nadi, Navosa 9665 Andrews Kindergarten Lautoka- 6707679 [email protected] Nadi College P O Box 1050, Nadi, Yasawa Road 8422 ANGEL KEEPERS Suva 8036739/9278 MAKOI LOT 26 KIA STREET, KINDERGARTEN 657 MAKOI 9006 Arya Kanya Ba-Tavua 6674107 1051aryakanyapathshala@gmail. Yalalevu P O BOX 106 Ba Kindergarten com 9565 Arya Samaj Suva 3381194 / [email protected] 2. 5 Miles, P O Box 3877, Kindergarten Suva 2011497 / Samabula Samabula, 9220014 9776 Arya Samaj Natabua Lautoka- 6660127 [email protected] Natabua P O Box 1035, Ktn Yasawa Housing Lautoka, Settlement 9826 Avea Kindergarten Eastern 7458 162 [email protected] Avea Island, C/- Avea Primary Vanuabalav School, P O u, Lau Lomaloma, Vanuabalavu 9767 Ba Andhra Ba-Tavua 4501144 [email protected] Ba P O Box 429, Ba, Kindergarten 9018 Ba Muslim Ba-Tavua 6674485 [email protected] Yalalevu, Ba. -

Republic of the Fiji Islands State Cedaw 2Nd, 3Rd & 4Th Periodic Report

ANNEXES TO THE COMBINED SECOND, THIRD AND FOURTH PERIODIC REPORT OF FIJI (CEDAW/C/FJI/2-4) REPUBLIC OF THE FIJI ISLANDS STATE CEDAW 2ND, 3RD & 4TH PERIODIC REPORT NOVEMBER 2008 Annexes ANNEX 1 CONCLUDING COMMENTS CEDAW RECOMMENDATION AND STATUS OF IMPLEMENTATION in FIJI Concerns Recommendation Response 1.Constitution of 1997 does Proposed constitution In fact the Constitution covers not contain the definition of reform should address the ALL FORMS of Discrimination discrimination against women need to incorporate the in section 38(2). The definition of definition of discrimination discrimination is contained in the Human Rights Commission Act at section 17 (1) and (2). 2. Absence of effective The government to include The Human Rights Commission mechanisms to challenge a clear procedure for the Act 10/99 is Fiji’s EEO law- see discriminatory practices and enforcement of section 17 for application to the enforce the right to gender fundamental rights and private sphere and employment. equality guaranteed by the enact an EEO law to cover FHRC also handles complaints constitution in respect of the the actions of non-state by women on a range of issues. actions of public officials and actors. (Reports Attached as Annex 2). non-state actors. 3.CEDAW is not specified in Expansions of the FHRC’s NOT TRUE. FHRC has a broad, and the mandate of the Fiji Human mandate to include not specific, mandate and therefore Rights Commission and that its CEDAW and that the deals with all discrimination including not assured funds to continue commission is provided gender. In response to the Concluding its work with adequate resources Comments of the UN CEDAW from State funds.