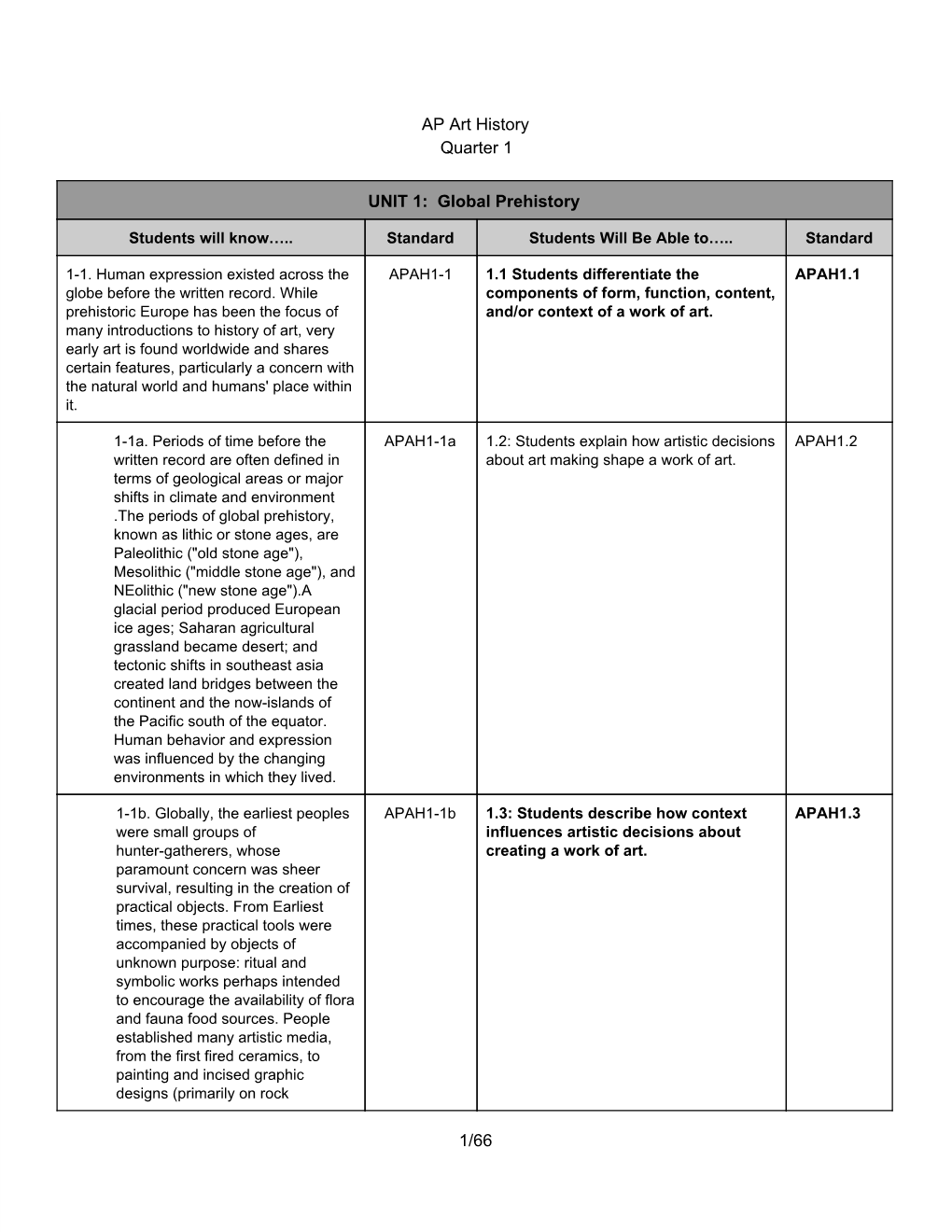

AP Art Historyаа Quarter 1 UNIT 1:Ааglobal Prehistory 1/66

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WAR and VIOLENCE: NEOCLASSICISM (Poussin, David, and West) BAROQUE ART: the Carracci and Poussin

WAR and VIOLENCE: NEOCLASSICISM (Poussin, David, and West) BAROQUE ART: The Carracci and Poussin Online Links: Annibale Carracci- Wikipedia Carracci's Farnese Palace Ceiling – Smarthistory Carracci - Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History Poussin – Wikipedia Poussin's Et in Arcadia Ego – Smarthistory NEOCLASSICISM Online Links: Johann Joachim Winckelmann - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Jacques-Louis David - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Oath of the Horatii - Smarthistory David's The Intervention of the Sabine Women – Smarthistory NEOCLASSICISM: Benjamin West’s Death of General Wolfe Online Links: Neoclassicism - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Benjamin West - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Death of General Wolfe - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Death of General Wolfe – Smarthistory Death of General Wolfe - Gallery Highlights Video Wolfe Must Not Die Like a Common Soldier - New York Times NEOCLASSICISM: Jacques Louis David’s Death of Marat Online Links: Jacques-Louis David - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia The Death of Marat - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Charlotte Corday - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Art Turning Left - The Guardian Annibale Carracci. Flight into Egypt, 1603-4, oil on canvas The Carracci family of Bologna consisted of two brothers, Agostino (1557-1602) and Annibale (1560-1609), and their cousin Ludovico (1556-1619). In Bologna in the 1580s the Carracci had organized gatherings of artists called the Accademia degli Incamminati (academy of the initiated). It was one of the several such informal groups that enabled artists to discuss problems and practice drawing in an atmosphere calmer and more studious than that of a painter’s workshop. The term ‘academy’ was more generally applied at the time to literary associations, membership of which conferred intellectual rank. -

Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras YEN-WEN CHENG University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Asian Art and Architecture Commons, Asian History Commons, and the Cultural History Commons Recommended Citation CHENG, YEN-WEN, "Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 98. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/98 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Tradition and Transformation: Cataloguing Chinese Art in the Middle and Late Imperial Eras Abstract After obtaining sovereignty, a new emperor of China often gathers the imperial collections of previous dynasties and uses them as evidence of the legitimacy of the new regime. Some emperors go further, commissioning the compilation projects of bibliographies of books and catalogues of artistic works in their imperial collections not only as inventories but also for proclaiming their imperial power. The imperial collections of art symbolize political and cultural predominance, present contemporary attitudes toward art and connoisseurship, and reflect emperors’ personal taste for art. The attempt of this research project is to explore the practice of art cataloguing during two of the most important reign periods in imperial China: Emperor Huizong of the Northern Song Dynasty (r. 1101-1125) and Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (r. 1736-1795). Through examining the format and content of the selected painting, calligraphy, and bronze catalogues compiled by both emperors, features of each catalogue reveal the development of cataloguing imperial artistic collections. -

Economic Dimensions of Precious Metals, Stones, and Feathers: the Aztec State Society

ECONOMIC DIMENSIONS OF PRECIOUS METALS, STONES, AND FEATHERS: THE AZTEC STATE SOCIETY FRANCES F. BERDAN In the spring of 1519, Hernán Cortés and his band of Spanish conquistadores feasted their eyes on the wealth of an empire. While resting on the coast of Veracruz, before venturing inland, Cortés was presented with lavish gifts from the famed Aztec emperor Mocte· zuma IV- While only suggestive of the vastness of imperial wealth, these presents included objects of exquisite workmanship fashioned of prized materials: gold, silver, feathers, jadeite, turquoise.2 There was an enormous wheel of gold, and a smaller one of silver, one said to represent the sun, the other the moon. There were two impressive collars (necklaces) of gold and stone mosaic work: they combined red stones, green stones, and gold bells. s There were fans and other elabo 1 Saville (1920: 20-39, 191-206) provides a detailed summary of the many accounts of the gifts presented to Cortés on this occasion. 2 Up to this point in their adventure, sorne of the conquistadores apparently had been sorely disappointed in the mainland's wealth. Bernal Diaz del Castillo repeatedly refers to the gold encountered by the Hernández de Córdova and Gri jalva expeditions (1517 and 1518, respectively) as "Iow grade" or "inferior", and small in quantity (Díaz del Castillo, 1956: 8, 22,23, 25, 28). While Díaz, writing many years after the events he describes, seems especially critical of the quality of the gold avaiJable on the coast, the friar Juan Díaz's account of the Grijalva ex pedition betrays no such dísappointment. -

Yoruba Art & Culture

Yoruba Art & Culture Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology University of California, Berkeley Yoruba Art and Culture PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY Written and Designed by Nicole Mullen Editors Liberty Marie Winn Ira Jacknis Special thanks to Tokunbo Adeniji Aare, Oduduwa Heritage Organization. COPYRIGHT © 2004 PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY AND THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PHOEBE A. HEARST MUSEUM OF ANTHROPOLOGY ◆ UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA AT BERKELEY BERKELEY, CA 94720-3712 ◆ 510-642-3682 ◆ HTTP://HEARSTMUSEUM.BERKELEY.EDU Table of Contents Vocabulary....................4 Western Spellings and Pronunciation of Yoruba Words....................5 Africa....................6 Nigeria....................7 Political Structure and Economy....................8 The Yoruba....................9, 10 Yoruba Kingdoms....................11 The Story of How the Yoruba Kingdoms Were Created....................12 The Colonization and Independence of Nigeria....................13 Food, Agriculture and Trade....................14 Sculpture....................15 Pottery....................16 Leather and Beadwork....................17 Blacksmiths and Calabash Carvers....................18 Woodcarving....................19 Textiles....................20 Religious Beliefs....................21, 23 Creation Myth....................22 Ifa Divination....................24, 25 Music and Dance....................26 Gelede Festivals and Egugun Ceremonies....................27 Yoruba Diaspora....................28 -

Christie's Presents Jewels: the Hong Kong Sale

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE October 28, 2008 Contact: Kate Swan Malin +852 2978 9966 [email protected] CHRISTIE’S PRESENTS JEWELS: THE HONG KONG SALE Jewels: The Hong Kong Sale Tuesday, December 2 Christie’s Hong Kong Hong Kong – Christie’s announces the fall sale of magnificent jewellery, Jewels: The Hong Kong Sale, which will take place on December 2 at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre. This sale features an exquisite selection of over 300 extraordinary jewels across a spectrum of taste and style, from masterpieces of the Belle Époque to contemporary creations, and from the rarest of white and coloured diamonds to important coloured stones. COLOURLESS DIAMONDS Leading the auction is a rare pair of D colour, Flawless diamonds weighing 16.11 and 16.08 carats (illustrated right, estimate: HK$40,000,000-60,000,000 / US$5,000,000-8,000,000). These marvellous stones are also graded ‘Excellent’ for polish, symmetry and cut grade, making them exceedingly rare for their superb quality. Classified as Type IIa, these diamonds are the most the chemically pure type of diamonds known, with no traces of the colorant nitrogen. The absence of this element, seen in 98% of diamonds, gives these stones a purity of colour and degree of transparency that is observed only in the finest white diamonds. The modern round brilliant cut is the diamond’s most basic and popular shape, as it allows the potential for the highest degree of light return. But more importantly, the round diamond sustains the highest value as its production requires riddance of the greatest amount of diamond rough. -

Prehistoric Art: Their Contribution for Understanding on Prehistoric Society

Prehistoric Art: Their Contribution for Understanding on Prehistoric Society Sofwan Noerwidi Balai Arkeologi Yogyakarta The pictures indicated as an art began their human invasion of the symbolic world, just started around 100.000 BP and more intensively since 30.000 years. The meaning of the relations between the men and with their world is produced by organization of representations in graphic systems by images, expression and communication in the same time. Since the first appearance of genus Homo, the development of cerebral and social evolution probably causes the ability to symbolize. Human uses the image to the modernity which is gives a symbolic way to the meaning for the beings and to the things (Vialou, 2009). This paper is a short report about development of contribution on study of symbolic behavior for interpreting of prehistoric society, from beginning period until recent times by several scholars. When late nineteenth and early twentieth century scientists have accept that Upper Paleolithic art is being genuinely of great antiquity. At that times, paleolithic art was interpreted merely as “art for art’s sake”. The first systematic study of Ice Age art was undertaken by Abbé Henri Breuil, a great French archeologist. He carefully copied images from a lot of sites and reconstructs a development chronology based on artistic style during the first half of the twentieth century. He believed that the art would grow more complicated through time (Lewin, et.al., 2004). After the beginning study by Breuil, as a summary they are several contributions on study of symbolic behavior for interpreting of prehistoric society, such as for reconstruction of prehistoric religion, social structure of their society, information exchange system between them, and also as indication of cultural and historical change in prehistoric times. -

Sculptors' Jewellery Offers an Experience of Sculpture at Quite the Opposite End of the Scale

SCULPTORS’ JEWELLERY PANGOLIN LONDON FOREWORD The gift of a piece of jewellery seems to have taken a special role in human ritual since Man’s earliest existence. In the most ancient of tombs, archaeologists invariably excavate metal or stone objects which seem to have been designed to be worn on the body. Despite the tiny scale of these precious objects, their ubiquity in all cultures would indicate that jewellery has always held great significance.Gold, silver, bronze, precious stone, ceramic and natural objects have been fashioned for millennia to decorate, embellish and adorn the human body. Jewellery has been worn as a signifier of prowess, status and wealth as well as a symbol of belonging or allegiance. Perhaps its most enduring function is as a token of love and it is mostly in this vein that a sculptor’s jewellery is made: a symbol of affection for a spouse, loved one or close friend. Over a period of several years, through trying my own hand at making rings, I have become aware of and fascinated by the jewellery of sculptors. This in turn has opened my eyes to the huge diversity of what are in effect, wearable, miniature sculptures. The materials used are generally precious in nature and the intimacy of being worn on the body marries well with the miniaturisation of form. For this exhibition Pangolin London has been fortunate in being able to collate a very special selection of works, ranging from the historical to the contemporary. To complement this, we have also actively commissioned a series of exciting new pieces from a broad spectrum of artists working today. -

Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures

www.idosr.org Ahmed ©IDOSR PUBLICATIONS International Digital Organization for Scientific Research ISSN: 2579-0765 IDOSR JOURNAL OF CURRENT ISSUES IN SOCIAL SCIENCES 6(1): 45-49, 2020. Influence of Science on Ancient Greek Sculptures Ahmed Wahid Yusuf Department of Museum Studies, Menoufia University, Egypt. ABSTRACT The Greeks made major contributions to math and science. We owe our basic ideas about geometry and the concept of mathematical proofs to ancient Greek mathematicians such as Pythagoras, Euclid, and Archimedes. Some of the first astronomical models were developed by Ancient Greeks trying to describe planetary movement, the Earth’s axis, and the heliocentric system a model that places the Sun at the center of the solar system. The sculpture of ancient Greece is the main surviving type of fine ancient Greek art as, with the exception of painted ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient Greek painting survives. The research further shows the influence science has in the ancient Greek sculptures. Keywords: Greek, Sculpture, Astronomers, Pottery. INTRODUCTION The sculpture of ancient Greece is the of the key points of Ancient Greek main surviving type of fine ancient Greek philosophy was the role of reason and art as, with the exception of painted inquiry. It emphasized logic and ancient Greek pottery, almost no ancient championed the idea of impartial, rational Greek painting survives. Modern observation of the natural world. scholarship identifies three major stages The Greeks made major contributions to in monumental sculpture in bronze and math and science. We owe our basic ideas stone: the Archaic (from about 650 to 480 about geometry and the concept of BC), Classical (480-323) and Hellenistic mathematical proofs to ancient Greek [1]. -

Art and Symbolism: the Case Of

ON THE EMERGENCE OF ART AND SYMBOLISM: THE CASE OF NEANDERTAL ‘ART’ IN NORTHERN SPAIN by Amy Chase B.A. University of Victoria, 2011 A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Archaeology Memorial University of Newfoundland May 2017 St. John’s, Newfoundland and Labrador ABSTRACT The idea that Neandertals possessed symbolic and artistic capabilities is highly controversial, as until recently, art creation was thought to have been exclusive to Anatomically Modern Humans. An intense academic debate surrounding Neandertal behavioural and cognitive capacities is fuelled by methodological advancements, archaeological reappraisals, and theoretical shifts. Recent re-dating of prehistoric rock art in Spain, to a time when Neandertals could have been the creators, has further fuelled this debate. This thesis aims to address the underlying causes responsible for this debate and investigate the archaeological signifiers of art and symbolism. I then examine the archaeological record of El Castillo, which contains some of the oldest known cave paintings in Europe, with the objective of establishing possible evidence for symbolic and artistic behaviour in Neandertals. The case of El Castillo is an illustrative example of some of the ideas and concepts that are currently involved in the interpretation of Neandertals’ archaeological record. As the dating of the site layer at El Castillo is problematic, and not all materials were analyzed during this study, the results of this research are rather inconclusive, although some evidence of probable symbolic behaviour in Neandertals at El Castillo is identified and discussed. -

Indian Art History from Colonial Times to the R.N

The shaping of the disciplinary practice of art Parul Pandya Dhar is Associate Professor in history in the Indian context has been a the Department of History, University of Delhi, fascinating process and brings to the fore a and specializes in the history of ancient and range of viewpoints, issues, debates, and early medieval Indian architecture and methods. Changing perspectives and sculpture. For several years prior to this, she was teaching in the Department of History of approaches in academic writings on the visual Art at the National Museum Institute, New arts of ancient and medieval India form the Delhi. focus of this collection of insightful essays. Contributors A critical introduction to the historiography of Joachim K. Bautze Indian art sets the stage for and contextualizes Seema Bawa the different scholarly contributions on the Parul Pandya Dhar circumstances, individuals, initiatives, and M.K. Dhavalikar methods that have determined the course of Christian Luczanits Indian art history from colonial times to the R.N. Misra present. The spectrum of key art historical Ratan Parimoo concerns addressed in this volume include Himanshu Prabha Ray studies in form, style, textual interpretations, Gautam Sengupta iconography, symbolism, representation, S. Settar connoisseurship, artists, patrons, gendered Mandira Sharma readings, and the inter-relationships of art Upinder Singh history with archaeology, visual archives, and Kapila Vatsyayan history. Ursula Weekes Based on the papers presented at a Seminar, Front Cover: The Ashokan pillar and lion capital “Historiography of Indian Art: Emergent during excavations at Rampurva (Courtesy: Methodological Concerns,” organized by the Archaeological Survey of India). National Museum Institute, New Delhi, this book is enriched by the contributions of some scholars Back Cover: The “stream of paradise” (Nahr-i- who have played a seminal role in establishing Behisht), Fort of Delhi. -

Denisovan News: Keeping These Remarkable Yet Enigmatic People up Front by Tom Baldwin

BUSINESSBUSINESS NAMENAME BUSINESSBUSINESS NAMENAME Pleistocene coalition news VOLUME 11, ISSUE 6 NOVEMBER-DECEMBER 2019 Inside -- ChallengingChallenging thethe tenetstenets ofof mainstreammainstream scientificscientific aagg e e n n d d a a s s -- We at PCN want to thank everyone for making our 10th Anniversary Issue (Issue #61, P A G E 2 September-October 2019) such a success and we thank everyone for writing us. Denisovan news: As most now realize, founding member and central figure of the Pleistocene Coaltiion, Dr. Vir- Keeping these re- markable though ginia Steen-McIntyre’s, recent stroke and other illnesses have become a concern for all those enigmatic people who know her and work Readers were taken by surprise with Tim Holmes’ up front with her as well as for our ‘Paleolithic human dispersals via natural floating readers. The loss of her Tom Baldwin platforms, Part 1 ’ last issue. crucial roles as writer, In contrast to presumed ocean P A G E 4 travel via sailing or paddling scientific advisor, core 10 years ago in PCN manmade watercraft Holmes PCN editor, writer organ- From comparing aerial Dr. Virginia Steen- suggested a third way has izer, etc., while she recov- views of the Middle East with South McIntyre’s first been downplayed in anthro- ers has also added to our A natural pumice raft African cir- In Their Own Words pology and readers re- other editors’ responsibili- cles over column sponded, asking, “Why is this idea not better ties and difficulty in keep- known?” Holmes is still working to finish Part 2. 6,000 miles Virginia Steen-McIntyre ing up. -

Lesson #1: Architecture Features Through the Ages

Unit Two: History of Architecture and Building Codes Lesson #1: Architecture Features Through the Ages Objectives Students will be able to… . Summarize the architecture features through Stone Ages to Neo-Classical Time. Common Core Standards LS 11-12.6 RSIT 11-12.2 RLST 11-12.2 Problem Solving/Critical Thinking 5.4 Health and Safety 6.2, 6.3, 6.4, 6.5, 6.6, 6.12 Technical Knowledge and Skills 10.1, 10.2, 10.3 Residential and Commercial Construction Pathway D2.1, D2.8, D2.9, D3.1, D3.2, D3.3, D3.4, D3.7 Responsibility and Leadership 7.4, 9.3 Materials Architecture Features Through the Ages Power Point https://documentcloud.adobe.com/link/track?uri=urn%3Aaaid%3Ascds%3AUS%3Ab4f485df -0d78-4fa9-9509-0b9ea3e1952c Architecture Features Through the Ages Worksheet Lesson Sequence . Introduce to students that a specific architectural style is characterized by a collection of design details. These details include size and shape of windows, the size and placement of a porch, and the presence or absence of columns. Review the Architecture Features Through the Ages PowerPoint with students. Have students fill in the Architecture Features Through the Ages Worksheet while reviewing the power point. Discuss and answer any questions students may have along the way. © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR TWO CURRICULUM Assessment Check for understanding while presenting PowerPoint. Grade student worksheets. Reteach and clarify any misunderstandings as needed. Accommodations/Modifications Check for Understanding One on One Support Peer Support Extra Time If Needed © BITA: A program promoted by California Homebuilding Foundation BUILDING INDUSTRY TECHNOLOGY ACADEMY: YEAR TWO CURRICULUM Architecture Features Through the Ages Worksheet As you watch the PowerPoint on Architectural Features Through the Ages fill in summary with the correct answers.