Burnside of Duntrune: an Essay in Praise of Ordinariness W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mobile Library Timetable 2021

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE 2021 Week 1 - Van 1 - Isla Week 2 - Van 1 – Isla Beginning Monday 26th April 2021 Beginning Monday 3rd May 2021 MONDAY – APR 26 | MAY 10, 24 | JUN 7, 21 | JUL 5, MONDAY – MAY 3 (public holiday), 17, 31 | JUN 14, 28 19 | AUG 2, 16, 30 | SEP 13, 27 | JUL 12, 26 | AUG 9, 23 | SEP 6, 20 10:25-10:55 Wellbank (by school) 10:00-10:30 Inverarity (by school) 11:00-11:20 Wellbank (Gagiebank) 10:45-11:15 Tealing (by school) 11:35-12:05 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 11:30-12:00 Strathmartine (by school) 12:40-12:55 Newbigging (Templehall Gardens) 12:50-13:20 Craigton of Monikie (by school) 13:00 -13:20 Newbigging (by School) 13:25-13:50 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 13:35-13:55 Forbes of Kingennie (Car Park Area) 14:00-14:25 Balumbie (Silver Birch Drive) 14:25 -14:45 Strathmartine (Ashton Terrace) 14:30-14:55 Balumbie (Poplar Drive) 15:10-15:30 Ballumbie (Oak Loan) 15:10-15:30 Murroes Hall 15:35-15:55 Ballumbie (Elm Rise) 15:40-16:00 Inveraldie Hall TUESDAY – APR 27 | MAY 11, 25 | JUN 8, 22 | JUL 6, TUESDAY – MAY 4, 18 | JUN 1, 15, 29 | JUL 13, 27 | 20 | AUG 3, 17, 31 | SEP 14, 28 AUG 10, 24 | SEP 7, 21 10:10-10:30 Guthrie (By Church) 10:00 -10:25 Kingsmuir (Dunnichen Road) 10:35-11:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) 10:50-11:25 Arbirlot (by School) 11:20-12:00 Dunnichen (By Church) 11:30-11:45 Balmirmer 11:55-12:20 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 12:10-12:30 Bowriefauld 13:30-13:50 Muirdrum 13:30-14:00 Barry Downs (Caravan Park) 14:05-14:30 Letham (Jubilee Court) 14:20-14:50 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 14:35-15:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) -

Mobile Library Route Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE Week 1 - Van 2 Week 2 - Van 1 Week 1 - Van 2 Week 2 - Van 1 Begining Mon 2 Oct 2017 Begining Mon 9 Oct 2017 Begining Mon 2 Oct 2017 Begining Mon 9 Oct 2017 Monday dates Monday dates Monday dates Monday dates 2 oct | 16 oct | 30 oct | 13 nov 9 oct | 23 oct | 6 nov | 20 nov 2 oct | 16 oct | 30 oct | 13 nov 9 oct | 23 oct | 6 nov | 20 nov 27 nov | 11 dec | 25 dec Hol | 8 Jan 4 dec | 18 dec | 1st Jan Hol 27 nov | 11 dec | 25 dec Hol | 8 Jan 4 dec | 18 dec | 1st Jan Hol LUNANHEAD: MID ROW ..................... 10:15-10:35 LUNANHEAD: MID ROW ..................... 10:15-10:35 WELLBANK: by PS ............................... 10:45-11:45 INVERARITY ......................................... 10:00-10:20 LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES ........ 10:40-11:00 LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES ........ 10:40-11:00 WELLBANK: GAGIEBANK..................... 11:50-12:05 TEALING .............................................. 10:40-11:10 TANNADICE ......................................... 11:20-11:40 ABERLEMNO ....................................... 11:15-11:45 WELLBANK HALL ................................ 12:10-12:25 STRATHMARTINE: ASHTON TCE ........... 11:30-12:00 MEMUS ............................................... 11:55-12:20 MONIKIE: BROOMWELL GDNS ............ 13:10-13:30 LITTLE BRECHIN .................................. 12:10-12:30 NORANSIDE ........................................ 13:05-13:25 WELLBANK HALL ................................. 12:45-13:15 MONIKIE: SHOP .................................. 13:35-13:50 EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL ............ 13:20-14:10 KIRKTON OF MENMUIR ....................... 13:45-14:05 CRAIGTON OF MONIKIE: CAR PARK .... 13:30-14:30 CRAIGTON OF MONIKIE ...................... 13:55-14:15 EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL .................... 14:15-14:45 INCHBARE ........................................... 14:20-14:40 MONIKIE: BROOMWELL GDNS ........... -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Mobile Library Route Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICE JOIN US AND BEGIN YOUR JOURNEY Week 1 (begins Monday 2nd Oct 2017) VAN 2 Week 2 (begins Monday 9th Oct 2017) VAN 1 Day/Date Location Time Day/Date Location Time Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 2 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 9 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 16 Oct ABERLEMNO 11.15-11.45 23 Oct TANNADICE 11.20-11.40 30 Oct LITTLE BRECHIN 12.10-12.30 6 Nov MEMUS 11.55-12.20 13 Nov EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL 13.20-14.10 20 Nov NORANSIDE 13.05-13.25 27 Nov EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL 14:15-14:45 4 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 13.45-14.05 11 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 15.15-15.45 18 Dec INCHBARE 14.20-14.40 25 Dec Holiday NORANSIDE 16.00-16.30 1st Jan Holiday EDZELL: BY PS 14.55-15.45 8 Jan MEMUS 16.40-17.05 EDZELL: INGLIS COURT 15.55-16.20 TANNADICE 17.15-17.45 EDZELL: CHURCH ST 16.30-16.45 WATERSTON ROAD 18.00-18.20 EDZELL: MEMORIAL HALL 16.50-17.20 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.40-19.00 LITTLE BRECHIN 17.55-18.15 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.35-19.00 Tuesdays CORTACHY: by PS 10.15-11.00 Tuesdays PADANARAM 10.00-10.20 3 Oct DYKEHEAD: TULLOCH WYND 11.10-11.30 10 Oct NEWTYLE: CHURCH ST 10.45-11.50 17 Oct KINGOLDRUM 12.00-12.30 24 Oct NEWTYLE: SOUTH ST 11.55-12.15 31 Oct AIRLIE HALL 13.30-13.50 7 Nov NEWTYLE: KINPURNEY GDNS 12.20-12.40 14 Nov WESTMUIR: POST OFFICE 14.00-14.30 21 Nov EASSIE HALL 13.25-13.40 28 Nov WESTMUIR: DAVID LAWSON GDNS 14.45-15.05 5 Dec GLAMIS: STRATHMORE ROAD 13.55-14.10 12 Dec GLAMIS: SQUARE 15.15-15.35 19 Dec GLAMIS: by SCHOOL 14.15-15.00 26 Dec Holiday CHARLESTON -

Bus Timetable Tealing - Inveraldie - Murroes - Dundee (Includes All Services Between Murroes and Dundee)

Services 139 Bus Timetable Tealing - Inveraldie - Murroes - Dundee (includes all services between Murroes and Dundee) From 5 June 2017 Leaflet 29 Passenger Information This leaflet contains details of local bus service 139, which runs between Tealing, Inveraldie, Murroes and Dundee City Centre. It also includes the section of local bus service 22 that runs between Murroes and Dundee. The publication is effective from Monday 5 June 2017. Changes to Service 139 since the August 2016 edition of this timetable • There is an additional Monday to Friday service 139 journey commencing Dundee High Street at 08:40; • The Monday to Friday service 139 journey from Dundee at 10:10 is withdrawn; • The Monday to Friday 07:48 service 139 journey from Inveraldie to Dundee is now operated by Stagecoach Strathtay and commences 4 minutes earlier at 07:44; • The Saturday service 139 journey from Dundee at 08:50 now commences 10 minutes earlier at 08:40; this also affects the return journey from Inveraldie now departing 7 minutes earlier at 09:02; • The Monday to Friday and Saturday service 139 journey from Dundee at 12:30 now commences 5 minutes earlier at 12:25; this also affects the return journey from Inveraldie which now departs 6 minutes earlier at 13:00. Operator of the bus services shown in this leaflet Xplore Dundee, 44-48 East Dock Street, Dundee DD1 3JS Tel: Dundee (01382) 201121, office hours only Web: www.nxbus.co.uk/dundee Email: [email protected] Service 22 and one service 139 journey is operated by: Stagecoach Strathtay, Arbroath Bus Station, Catherine Street, Arbroath DD11 1RL Tel: Arbroath (01241) 870646, office hours only Web: www.stagecoachbus.com Email: [email protected] Further information on the services in this booklet can be obtained from the relevant operator on the numbers above. -

Murroes & Wellbank Community Council

MURROES & WELLBANK COMMUNITY COUNCIL Virtual TEAMS meeting held on Thursday 22nd April 2021 at 7.30pm. Present: S. Anderson(Chair/Planning); A. Martin(Vice Chair); G. Reid(Treas); Cllr B. Whiteside; Cllr S. Hands; I. Robertson(Stop the Crem); B. Jack; J. Crozier; G. Cowper(Secy). K. Gerrard. Apologies: D. Murdoch; A. Fraser; J. Bell; D. McNeil(Angus Council) The Chair opened the meeting and welcomed everyone. Everyone attending was asked to introduce themselves. It was asked if anyone attending the meeting would be interested in becoming a Minute Taker, to please remain behind at the end of the meeting when more information would be given. Minutes of Previous Meeting These were read and approved. Matters Arising Proposed Crematorium IR asked if the Architect for the Crematorium application had been requested to attend the previous meeting or had he invited himself. He was informed the Architect had contacted GC in January and was invited to attend the meeting in February. He did not attend. Update IR, State of limbo since last meeting. Applicant was required to submit two items by the end of February, one was an updated transport assessment which has been carried out, it was a very minor point changed, concerning the Shank of Omachie development traffic, something the Planning Officer requested, the Roads Department response still quite concerning. The Crematorium would bring a 37% traffic uplift during its opening hours, the Council had stated anything more than 5-10% was significant, but they haven’t commented on that. The roads to the North and West of the site, past Duntrune House, out past Burnside of Duntrune over the bridge and also North past the school and Westhall Terrace, none of that had been commented on in terms of any issues and improvements. -

The Forfar Directory and Yearbook 1906

FORFAR PUBLIC LIBRARY ILOCAIL C©IL!LiCTD@ No. Presented by ANGUS - CULTURAL SERVICES 3 8046 00947 081 5 ^c^^v. 21 DAYS ALLOWED FOR READING THIS BOOK. Overdue Books Charged at Ip per Day. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/forfardirectoryy1906unse : cr^ THE T)c-^-^X FORFAR DIRFCTORY .x^. AND YEAR BOOK K^^ FOR 1906 1906 CONTAINING LIST OF THE HOUSEHOLDERS OF THE BURGH, DIRECTORY OF TRADES AND PROFESSIONS, LIST OF PUBLIC BOARDS, SOCIETIES, ETC. ETC. ETC. ALSO, ,.,.-.*.,_, LIST OF FARMERS AND OTHERS IN THE ADJOINING PARISHES. C V- l: FORFAR STREET. j PRINTED & PUBLISHED BY W. SHEPHERD, CASTLE 1905. ^-is^n^-^ — —. CONTENTS. Page Page Angling Clubs 66 Householders, Male .. 5-36 Bakers' Society ... 68 Infirmary 62 Bank Offices 6i Instrumental Band 62 68 Bible Society . 63 Joiners' Association Blind, Mission to the . 63 Justices of the Peace (Forfar) 59 Bowling Clubs ... 66 Library, Public ... 61 Building Societies 68 Liberal and Radical Association .. 63 Burgh Funds 58 Literary Institute .. 63 .. Celtic Society . 63 Magistrates and Town Council 58 66 Charity Mortifications 59 Masonic Lodges .. 61 Chess Club . 63 Museum, Forfar Children's Church 64 Nursing Association .. 64 Children's League of Pity 68 Oddfellows' Lodge 66 Choral Union ... 62 Parish Council ... 61 Christian Association, Young Men's 62 Philharmonic Society 62 Do. do. , Young Wome n's 62 Plate Glass Insurance Association 65 Churches 61 Post Office Arrangements 52 Church Services, &c. 63-64 Poultry Association 67 Coal Societies 66 Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 68 Conservative Association .. -

Audit of Housing Land in Dundee and Angus 2003

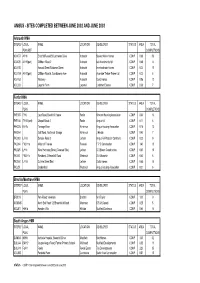

ANGUS - SITES COMPLETED BETWEEN JUNE 2002 AND JUNE 2003 Arbroath HMA SITEREF LOCAL NAME LOCATION DEVELOPER STATUS AREA TOTAL PLAN REF COMPLETIONS ACA077 A/H1l Elliot St/Russell St/Lochlands Drive Arbroath Stewart Milne Homes COMP 0.88 50 ACA081 A/H1f(part) Cliffburn Road 2 Arbroath Isla Investments ltd COMP 0.48 14 ACA152 Howard Street/Baldovan Street Arbroath Inverbrothock Homes COMP 0.24 15 ACA159 A/H1f(part) Cliffburn Road 4, Donaldsons Acre Arbroath Avonside Timber Frame Ltd COMP 0.20 6 ACA162 Westway Arbroath Guild Homes COMP 0.96 12 ACL023 Leysmill Farm Leysmill Linlathen Estates COMP 0.38 7 Forfar HMA SITEREF LOCAL NAME LOCATION DEVELOPER STATUS AREA TOTAL PLAN COMPLETIONS FKF085 F/H6 Lour Road, Beechhill House Forfar Kirkcare Housing Association COMP 0.64 16 FKF105 F/H12(part) Chapel Street 2 Forfar Angus HA COMP 0.11 6 FKK025 K/H1c Tannage Brae Kirriemuir Angus Housing Association COMP 0.16 13 FKK064 Golf Road, Northmuir Garage Kirriemuir J Hardie COMP 0.40 7 FKL003 L/H1a Dundee Road 2 Letham Angus HA/Webster Contracts COMP 0.20 9 FKL014 FKL/H1a Milton of Finavon Finavon F P C Construction COMP 1.40 18 FKL025 L/H1c West Hemming Street (Caravan Site) Letham G S Brown Construction COMP 0.60 19 FKL031 FKL/H1c Westbank 2, Heardhill Road Westmuir D A Mcmartin COMP 0.60 8 FKL148 L/H1d Guthrie Street East Letham Guild Homes COMP 0.65 14 FKL251 Gradonfield Westmuir Angus Housing Association COMP 0.21 6 Brechin/Montrose HMA SITEREF LOCAL NAME LOCATION DEVELOPER STATUS AREA TOTAL PLAN COMPLETIONS BRB016 Park Road, Viewbank Brechin Mr I -

Angus Council Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 Angus

ANGUS COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 ANGUS COUNCIL (MONIKIE- BARRY ROAD, CARNOUSTIE AND A92 DUNDEE - ARBROATH - MONTROSE - STONEHAVEN ROAD, MONTROSE) ) (VARIATION OF SPEED LIMITS) ORDER 2020 2020 RB Director of Legal and Democratic Services Angus Council Angus House Orchardbank Business Park Forfar ANGUS COUNCIL ROAD TRAFFIC REGULATION ACT 1984 ANGUS COUNCIL (MONIKIE - BARRY ROAD, CARNOUSTIE AND A92 DUNDEE - ARBROATH - MONTROSE - STONEHAVEN ROAD, MONTROSE) (VARIATION OF SPEED LIMITS) ORDER 2020 Angus Council in exercise of the powers conferred on them by Sections 84(1) and 124(1) of, and Part IV of Schedule 9 to, the Road Traffic Regulation Act 1984 as amended (which Act of 1984 is hereinafter referred to as "the Act") and of all other powers enabling them in that behalf and after consultation with the Chief Constable in accordance with Paragraph 20(1) of Schedule 9 to the Act hereby make the following Order:- 1. This Order may be cited as the " Angus Council (Monikie - Barry Road, Carnoustie and A92 Dundee - Arbroath - Montrose - Stonehaven Road, Montrose) (Variation of Speed Limits) Order 2020" and shall come into operation on the Twenty Eighth day of February Two thousand and Twenty . 2. The Order specified in the Schedule to this Order is hereby varied and shall henceforth have effect subject to the amendments thereto specified and described in the said Schedule. Made at Forfar on 10th February 2020 (Signed) R Blair (Witness) (Signed) Ian Andrew Cochrane Rebecca Dorothy Blair Ian Andrew Cochrane Paralegal Director of Infrastructure and Angus Council, Angus House, a Proper Officer of Angus Council Orchardbank Business Park, Forfar DD8 1AN This is the Schedule referred to in the foregoing Angus Council (Monikie - Barry Road, Carnoustie and A92 Dundee - Arbroath - Montrose - Stonehaven Road, Montrose) (Variation of Speed Limits) Order 2020. -

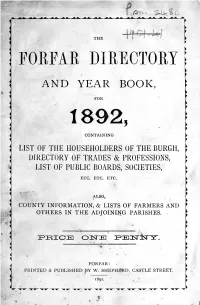

The Forfar Directory and Year Book

THE FORFAR DIRECTORY AND YEAR BOOK, FOR 1892, CONTAINING LIST OF THE HOUSEHOLDERS OF THE BURGH, DIRECTORY OF TRADES' & PROFESSIONS, LIST OF PUBLIC BOARDS, SOCIETIES, ETC. ETC. ETC. ALSO, COUNTY INFORMATION, & LISTS OF FARMERS AND OTHERS IN THE ADJOINING PARISHES. price onsriE zpiEiisnsrY- FORFAR : - PRINTED & PUBLISHED BY W. SHEPHERD, CASTLE STREET. 1891. ^ Vt-^^r- ^ ^ ^ ^ ^-^r W-^^ ^ ^ ^ m41;i : FORFAR DIRECTORY AND YEAR BOOK, 1892, CONTAINING LIST OF THE HOUSEHOLDERS OF THE BURGH, DIRECTORY OF TRADES & PROFESSIONS, LIST OF PUBLIC BOARDS, SOCIETIES, ETC. ETC. ETC. ALSO, COUNTY INFORMATION, & LISTS OF FARMERS AND OTHERS IN THE ADJOINING PARISHES. PEICE OISTE ZPEZN-HSrY- FORFAR 'RINTED & PUBLISHED BY W. SHEPHERD, CASTLE STREET. 1891. INDEX TO ADVERTISEMENTS. Page. Page. Abel & Simpson, Chemists i33 Mann, Joseph, Tailor.. .- .. no Adamson, John, Grocer, etc. .. Masterton, David, Plasterer .. .. in Andrew, William, Tobacconist, etc 126 Mathers, William, Watchmaker .. 122 Arnot, James M., Ironmonger.. 106 Melvin, B. & M., Grocers .. .. 102 . 126 Bell, Mrs, Draper, etc. 128 Milne, James, Coal Merchant Butchart, D., Grocer .. i39 Moffat, William, Slater . 132 Clark, James, Plumber Muir, T., Son, & Patton, Coal Merchants 144 Clark, John A., Watchmaker .. Munro, James, Architect, etc... .. 120 Currie, M'Dougall, & Scott, Wool Spi Munro, James, Toy Merchant, etc. nq ners, Galashiels 136 Murdoch, J. D., Watchmaker .. .. no Deuchar, Alex., Shoemaker i35 Neill, James, Music Teacher .. •• 112 Donald, David, Grocer, etc. .. 125 Nicolson, James, Grocer, etc. .. •• 137 Donald, Henry, Grocer 122 Oram, Miss, Milliner, etc. .. •• 129 .. •• •• 124 Ewen, James, Wood Merchant People's Journal _ Farquharson, Adam, Draper .. Petrie, John, Tailor .. .. •• 128 Ferguson, Miss, Berlin Wool Respo I3S Petrie, Thomas, Temperance Hotel . -

Mobile Library Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE 2021 Week 1 - Van 1 - Isla Week 2 - Van 1 – Isla Beginning Monday 26th April 2021 Beginning Monday 3rd May 2021 MONDAY – APR 26 | MAY 10, 24 | JUN 7, 21 | JUL 5, MONDAY – MAY 3 (public holiday), 17, 31 | JUN 14, 28 19 | AUG 2, 16, 30 | SEP 13, 27 | JUL 12, 26 | AUG 9, 23 | SEP 6, 20 10:25-10:55 Wellbank (by school) 10:00-10:30 Inverarity (by school) 11:00-11:20 Wellbank (Gagiebank) 10:45-11:15 Tealing (by school) 11:35-12:05 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 11:30-12:00 Strathmartine (by school) 12:40-12:55 Newbigging (Templehall Gardens) 12:50-13:20 Craigton of Monikie (by school) 13:00 -13:20 Newbigging (by School) 13:25-13:50 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 13:35-13:55 Forbes of Kingennie (Car Park Area) 14:00-14:25 Balumbie (Silver Birch Drive) 14:25 -14:45 Strathmartine (Ashton Terrace) 14:30-14:55 Balumbie (Poplar Drive) 15:10-15:30 Ballumbie (Oak Loan) 15:10-15:30 Murroes Hall 15:35-15:55 Ballumbie (Elm Rise) 15:40-16:00 Inveraldie Hall TUESDAY – APR 27 | MAY 11, 25 | JUN 8, 22 | JUL 6, TUESDAY – MAY 4, 18 | JUN 1, 15, 29 | JUL 13, 27 | 20 | AUG 3, 17, 31 | SEP 14, 28 AUG 10, 24 | SEP 7, 21 10:10-10:30 Guthrie (By Church) 10:00 -10:25 Kingsmuir (Dunnichen Road) 10:35-11:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) 10:50-11:25 Arbirlot (by School) 11:20-12:00 Dunnichen (By Church) 11:30-11:45 Balmirmer 11:55-12:20 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 12:10-12:30 Bowriefauld 13:30-13:50 Muirdrum 13:30-14:00 Barry Downs (Caravan Park) 14:00-14:30 Letham (Jubilee Court) 14:20-14:50 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 14:35-15:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) -

Mobile Library Service Join Us and Begin Your Journey

MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICE JOIN US AND BEGIN YOUR JOURNEY Week 1 (begins Monday 10th Jul 2017) VAN 2 Week 2 (begins Monday 3rd Jul 2017) VAN 1 Day/Date Location Time Day/Date Location Time Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 10 Jul LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 3 Jul LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 24 Jul ABERLEMNO 11.15-11.45 17 Jul TANNADICE 11.20-11.40 7 Aug LITTLE BRECHIN 12.10-12.30 31 Jul MEMUS 11.55-12.20 21 Aug EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL 13.20-14.10 14 Aug NORANSIDE 13.05-13.25 4 Sept EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL 14:15-14:45 28 Aug KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 13.45-14.05 18 Sept KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 15.15-15.45 11 Sept INCHBARE 14.20-14.40 NORANSIDE 16.00-16.30 25 Sept EDZELL: BY PS 14.55-15.45 MEMUS 16.40-17.05 EDZELL: INGLIS COURT 15.55-16.20 TANNADICE 17.15-17.45 EDZELL: CHURCH ST 16.30-16.45 WATERSTON ROAD 18.00-18.20 EDZELL: MEMORIAL HALL 16.50-17.20 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.40-19.00 LITTLE BRECHIN 17.55-18.15 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.35-19.00 Tuesdays CORTACHY: by PS 10.15-11.00 Tuesdays PADANARAM 10.00-10.20 NEWTYLE: CHURCH ST 10.45-11.50 11 Jul DYKEHEAD: TULLOCH WYND 11.10-11.30 4 Jul 25 Jul KINGOLDRUM 12.00-12.30 18 Jul NEWTYLE: SOUTH ST 11.55-12.15 NEWTYLE: KINPURNEY GDNS 12.20-12.40 8 Aug AIRLIE HALL 13.30-13.50 1 Aug 15 Aug EASSIE HALL 13.25-13.40 22 Aug WESTMUIR: POST OFFICE 14.00-14.30 29 Aug GLAMIS: STRATHMORE ROAD 13.55-14.10 5 Sept WESTMUIR: DAVID LAWSON GDNS 14.45-15.05 12 Sept GLAMIS: by SCHOOL 14.15-15.00 19 Sept GLAMIS: SQUARE 15.15-15.35 26 Sept WESTMUIR: DAVID LAWSON GDNS 15.20-15.45