University of Dundee DOCTOR of PHILOSOPHY

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2019 Scotch Whisky

©2019 scotch whisky association DISCOVER THE WORLD OF SCOTCH WHISKY Many countries produce whisky, but Scotch Whisky can only be made in Scotland and by definition must be distilled and matured in Scotland for a minimum of 3 years. Scotch Whisky has been made for more than 500 years and uses just a few natural raw materials - water, cereals and yeast. Scotland is home to over 130 malt and grain distilleries, making it the greatest MAP OF concentration of whisky producers in the world. Many of the Scotch Whisky distilleries featured on this map bottle some of their production for sale as Single Malt (i.e. the product of one distillery) or Single Grain Whisky. HIGHLAND MALT The Highland region is geographically the largest Scotch Whisky SCOTCH producing region. The rugged landscape, changeable climate and, in The majority of Scotch Whisky is consumed as Blended Scotch Whisky. This means as some cases, coastal locations are reflected in the character of its many as 60 of the different Single Malt and Single Grain Whiskies are blended whiskies, which embrace wide variations. As a group, Highland whiskies are rounded, robust and dry in character together, ensuring that the individual Scotch Whiskies harmonise with one another with a hint of smokiness/peatiness. Those near the sea carry a salty WHISKY and the quality and flavour of each individual blend remains consistent down the tang; in the far north the whiskies are notably heathery and slightly spicy in character; while in the more sheltered east and middle of the DISTILLERIES years. region, the whiskies have a more fruity character. -

Mobile Library Timetable 2021

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE 2021 Week 1 - Van 1 - Isla Week 2 - Van 1 – Isla Beginning Monday 26th April 2021 Beginning Monday 3rd May 2021 MONDAY – APR 26 | MAY 10, 24 | JUN 7, 21 | JUL 5, MONDAY – MAY 3 (public holiday), 17, 31 | JUN 14, 28 19 | AUG 2, 16, 30 | SEP 13, 27 | JUL 12, 26 | AUG 9, 23 | SEP 6, 20 10:25-10:55 Wellbank (by school) 10:00-10:30 Inverarity (by school) 11:00-11:20 Wellbank (Gagiebank) 10:45-11:15 Tealing (by school) 11:35-12:05 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 11:30-12:00 Strathmartine (by school) 12:40-12:55 Newbigging (Templehall Gardens) 12:50-13:20 Craigton of Monikie (by school) 13:00 -13:20 Newbigging (by School) 13:25-13:50 Monikie (Broomwell Gardens) 13:35-13:55 Forbes of Kingennie (Car Park Area) 14:00-14:25 Balumbie (Silver Birch Drive) 14:25 -14:45 Strathmartine (Ashton Terrace) 14:30-14:55 Balumbie (Poplar Drive) 15:10-15:30 Ballumbie (Oak Loan) 15:10-15:30 Murroes Hall 15:35-15:55 Ballumbie (Elm Rise) 15:40-16:00 Inveraldie Hall TUESDAY – APR 27 | MAY 11, 25 | JUN 8, 22 | JUL 6, TUESDAY – MAY 4, 18 | JUN 1, 15, 29 | JUL 13, 27 | 20 | AUG 3, 17, 31 | SEP 14, 28 AUG 10, 24 | SEP 7, 21 10:10-10:30 Guthrie (By Church) 10:00 -10:25 Kingsmuir (Dunnichen Road) 10:35-11:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) 10:50-11:25 Arbirlot (by School) 11:20-12:00 Dunnichen (By Church) 11:30-11:45 Balmirmer 11:55-12:20 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 12:10-12:30 Bowriefauld 13:30-13:50 Muirdrum 13:30-14:00 Barry Downs (Caravan Park) 14:05-14:30 Letham (Jubilee Court) 14:20-14:50 Easthaven (Car Park Area) 14:35-15:10 Letham (West Hemming Street) -

Scotch Malt Whisky Tour

TRAIN : The Royal Scotsman JOURNEY : Scotch Malt Whisky Tour Journey Duration : Upto 5 Days DAY 1 EDINBURG Meet your whisky ambassador in the Balmoral Hotel and enjoy a welcome dram before departure Belmond Royal Scotsman departs Edinburgh Waverley Station and travels north across the Firth of Forth over the magnificent Forth Railway Bridge. Afternoon tea is served as you journey through the former Kingdom of Fife. The train continues east along the coast, passing through Carnoustie, Arbroath and Aberdeen before arriving in the market town of Keith in the heart of the Speyside whisky region. After an informal dinner, enjoy traditional Scottish entertainment by local musicians. DAY 2 KYLE OF LOCHALSH Departing Keith this morning, the train travels west towards Inverness, capital of the Highlands. After an early lunch, disembark in Muir of Ord to visit Glen Ord Distillery, one of the oldest in Scotland. Enjoy a private tour of the distillery as well as a tasting and nosing straight from the cask. Back on board, relax as you enjoy the spectacular views on the way to Kyle of Lochalsh, on one of the most scenic routes in Britain. The line passes Loch Luichart and the Torridon Mountains, which geologists believe were formed before any life began. The train then follows the edge of Loch Carron through Attadale and Stromeferry before reaching the pretty fishing village of Plockton. This evening a formal dinner is served, followed by coffee and liqueurs in the Observation Car. DAY 3 CARRBRIDGE This morning, join a group of keen early-risers on a short, scenic trip to photograph the famous Eilean Donan Castle, one of Scotland’s most iconic sights. -

Mobile Library Route Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY TIMETABLE Week 1 - Van 2 Week 2 - Van 1 Week 1 - Van 2 Week 2 - Van 1 Begining Mon 2 Oct 2017 Begining Mon 9 Oct 2017 Begining Mon 2 Oct 2017 Begining Mon 9 Oct 2017 Monday dates Monday dates Monday dates Monday dates 2 oct | 16 oct | 30 oct | 13 nov 9 oct | 23 oct | 6 nov | 20 nov 2 oct | 16 oct | 30 oct | 13 nov 9 oct | 23 oct | 6 nov | 20 nov 27 nov | 11 dec | 25 dec Hol | 8 Jan 4 dec | 18 dec | 1st Jan Hol 27 nov | 11 dec | 25 dec Hol | 8 Jan 4 dec | 18 dec | 1st Jan Hol LUNANHEAD: MID ROW ..................... 10:15-10:35 LUNANHEAD: MID ROW ..................... 10:15-10:35 WELLBANK: by PS ............................... 10:45-11:45 INVERARITY ......................................... 10:00-10:20 LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES ........ 10:40-11:00 LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES ........ 10:40-11:00 WELLBANK: GAGIEBANK..................... 11:50-12:05 TEALING .............................................. 10:40-11:10 TANNADICE ......................................... 11:20-11:40 ABERLEMNO ....................................... 11:15-11:45 WELLBANK HALL ................................ 12:10-12:25 STRATHMARTINE: ASHTON TCE ........... 11:30-12:00 MEMUS ............................................... 11:55-12:20 MONIKIE: BROOMWELL GDNS ............ 13:10-13:30 LITTLE BRECHIN .................................. 12:10-12:30 NORANSIDE ........................................ 13:05-13:25 WELLBANK HALL ................................. 12:45-13:15 MONIKIE: SHOP .................................. 13:35-13:50 EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL ............ 13:20-14:10 KIRKTON OF MENMUIR ....................... 13:45-14:05 CRAIGTON OF MONIKIE: CAR PARK .... 13:30-14:30 CRAIGTON OF MONIKIE ...................... 13:55-14:15 EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL .................... 14:15-14:45 INCHBARE ........................................... 14:20-14:40 MONIKIE: BROOMWELL GDNS ........... -

The Forfar Directoryand Yearbook 1898

FORFAR PUBLIC LIBRARY No. Presented by ANGUS - CULTURAL SERVICES 3 8046 00947 088 IVY* 21 DAYS ALLOWED FOR READING THIS BOOK. Overdue Books Charged at lp per Day. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/forfardirectorya1898unse : THE FORFAR DIRECTORY ~<5>c. AND YEAR BOOK K5>, FOR 1808 I CONTAINING LIST OF THE HOUSEHOLDERS OF THE BURGH, DIRECTORY OF TRADES AND PROFESSIONS, LIST OF PUBLIC BOARDS, SOCIETIES, ETC. ETC. ETC. also, PROPERTY COUNTY INFORMATION, AND L.ST OF FARM©ls AND OTHlUs IN THE ADJOIMNG PARISHES. , ,- FORFAR PUBLIC LIBRARY PRICE OiETE—^EJIsrErYr" FORFAR PRINTED & PUBLISHED BY W. SHEPHERD, 39 CASTLE STREET. 1897. — CONTENTS. Page Page Angling Club 65 Horticultural Improvement Society 64 Bank Offices 60 Horticultural Society 64 Bible Society 62 Householders, Female 37-5° Blind, Mission to the 62 Householders, Male 5-37 Bowling Clubs ... Infirmary 65 59 Building Societies 67 Joiners' Association 67 Burgh Commissioners 58 Justices of thePeace (Forfar) 58 Burgh Funds Library, Public 57 ... 59 Charity Mortifications 58 Liberal and Radical Association 62 Children's Church 63 Literary Institute 62 Christian Association, Young Women's 61 Magistrates and Town Council Churches 57 60 Masonic Lodges ... 65 Church Services, &c. 62-63 Musical Societies 61 Coal Societies 64-65 Nursing Association 63 Conservative Association 61 Oddfellows' Lodge 65 County Information 68 Parish Council ... 59 Courts : Plate Glass Association ... 64 Burgh... 58 Post Office 56 Licensing, Burgh 58 Poultry Association 64 Police... 58 Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, Sheriff 68 Society for ... 67 Valuation Appeal 58 QuoitingClub .. -

Tullibardine Chapel Statement of Significance

Property in Care (PIC) ID: PIC106 Designations: Scheduled Monument (SM90308) Taken into State care: 1951 (Guardianship) Last Reviewed: 2020 STATEMENT OF SIGNIFICANCE TULLIBARDINE CHAPEL We continually revise our Statements of Significance, so they may vary in length, format and level of detail. While every effort is made to keep them up to date, they should not be considered a definitive or final assessment of our properties. Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH © Historic Environment Scotland 2020 You may re-use this information (excluding logos and images) free of charge in any format or medium, under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0 except where otherwise stated. To view this licence, visit http://nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open- government-licence/version/3 or write to the Information Policy Team, The National Archives, Kew, London TW9 4DU, or email: [email protected] Where we have identified any third party copyright information you will need to obtain permission from the copyright holders concerned. Any enquiries regarding this document should be sent to us at: Historic Environment Scotland Longmore House Salisbury Place Edinburgh EH9 1SH +44 (0) 131 668 8600 www.historicenvironment.scot You can download this publication from our website at www.historicenvironment.scot Historic Environment Scotland – Scottish Charity No. SC045925 Principal Office: Longmore House, Salisbury Place, Edinburgh EH9 1SH HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT -

Mobile Library Route Timetable

MOBILE LIBRARY SERVICE JOIN US AND BEGIN YOUR JOURNEY Week 1 (begins Monday 2nd Oct 2017) VAN 2 Week 2 (begins Monday 9th Oct 2017) VAN 1 Day/Date Location Time Day/Date Location Time Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 Mondays LUNANHEAD: MID ROW 10.15-10.35 2 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 9 Oct LUNANHEAD: PRIORY COTTAGES 10.40-11.00 16 Oct ABERLEMNO 11.15-11.45 23 Oct TANNADICE 11.20-11.40 30 Oct LITTLE BRECHIN 12.10-12.30 6 Nov MEMUS 11.55-12.20 13 Nov EDZELL: by PRIMARY SCHOOL 13.20-14.10 20 Nov NORANSIDE 13.05-13.25 27 Nov EDZELL MEMORIAL HALL 14:15-14:45 4 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 13.45-14.05 11 Dec KIRKTON OF MENMUIR 15.15-15.45 18 Dec INCHBARE 14.20-14.40 25 Dec Holiday NORANSIDE 16.00-16.30 1st Jan Holiday EDZELL: BY PS 14.55-15.45 8 Jan MEMUS 16.40-17.05 EDZELL: INGLIS COURT 15.55-16.20 TANNADICE 17.15-17.45 EDZELL: CHURCH ST 16.30-16.45 WATERSTON ROAD 18.00-18.20 EDZELL: MEMORIAL HALL 16.50-17.20 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.40-19.00 LITTLE BRECHIN 17.55-18.15 MILTON OF FINAVON 18.35-19.00 Tuesdays CORTACHY: by PS 10.15-11.00 Tuesdays PADANARAM 10.00-10.20 3 Oct DYKEHEAD: TULLOCH WYND 11.10-11.30 10 Oct NEWTYLE: CHURCH ST 10.45-11.50 17 Oct KINGOLDRUM 12.00-12.30 24 Oct NEWTYLE: SOUTH ST 11.55-12.15 31 Oct AIRLIE HALL 13.30-13.50 7 Nov NEWTYLE: KINPURNEY GDNS 12.20-12.40 14 Nov WESTMUIR: POST OFFICE 14.00-14.30 21 Nov EASSIE HALL 13.25-13.40 28 Nov WESTMUIR: DAVID LAWSON GDNS 14.45-15.05 5 Dec GLAMIS: STRATHMORE ROAD 13.55-14.10 12 Dec GLAMIS: SQUARE 15.15-15.35 19 Dec GLAMIS: by SCHOOL 14.15-15.00 26 Dec Holiday CHARLESTON -

The Forfar Directory and Yearbook 1906

FORFAR PUBLIC LIBRARY ILOCAIL C©IL!LiCTD@ No. Presented by ANGUS - CULTURAL SERVICES 3 8046 00947 081 5 ^c^^v. 21 DAYS ALLOWED FOR READING THIS BOOK. Overdue Books Charged at Ip per Day. Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2010 witii funding from National Library of Scotland http://www.archive.org/details/forfardirectoryy1906unse : cr^ THE T)c-^-^X FORFAR DIRFCTORY .x^. AND YEAR BOOK K^^ FOR 1906 1906 CONTAINING LIST OF THE HOUSEHOLDERS OF THE BURGH, DIRECTORY OF TRADES AND PROFESSIONS, LIST OF PUBLIC BOARDS, SOCIETIES, ETC. ETC. ETC. ALSO, ,.,.-.*.,_, LIST OF FARMERS AND OTHERS IN THE ADJOINING PARISHES. C V- l: FORFAR STREET. j PRINTED & PUBLISHED BY W. SHEPHERD, CASTLE 1905. ^-is^n^-^ — —. CONTENTS. Page Page Angling Clubs 66 Householders, Male .. 5-36 Bakers' Society ... 68 Infirmary 62 Bank Offices 6i Instrumental Band 62 68 Bible Society . 63 Joiners' Association Blind, Mission to the . 63 Justices of the Peace (Forfar) 59 Bowling Clubs ... 66 Library, Public ... 61 Building Societies 68 Liberal and Radical Association .. 63 Burgh Funds 58 Literary Institute .. 63 .. Celtic Society . 63 Magistrates and Town Council 58 66 Charity Mortifications 59 Masonic Lodges .. 61 Chess Club . 63 Museum, Forfar Children's Church 64 Nursing Association .. 64 Children's League of Pity 68 Oddfellows' Lodge 66 Choral Union ... 62 Parish Council ... 61 Christian Association, Young Men's 62 Philharmonic Society 62 Do. do. , Young Wome n's 62 Plate Glass Insurance Association 65 Churches 61 Post Office Arrangements 52 Church Services, &c. 63-64 Poultry Association 67 Coal Societies 66 Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, 68 Conservative Association .. -

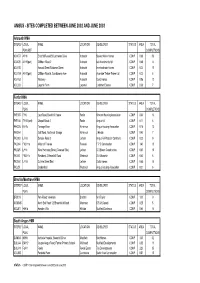

Audit of Housing Land in Dundee and Angus 2003

ANGUS - SITES COMPLETED BETWEEN JUNE 2002 AND JUNE 2003 Arbroath HMA SITEREF LOCAL NAME LOCATION DEVELOPER STATUS AREA TOTAL PLAN REF COMPLETIONS ACA077 A/H1l Elliot St/Russell St/Lochlands Drive Arbroath Stewart Milne Homes COMP 0.88 50 ACA081 A/H1f(part) Cliffburn Road 2 Arbroath Isla Investments ltd COMP 0.48 14 ACA152 Howard Street/Baldovan Street Arbroath Inverbrothock Homes COMP 0.24 15 ACA159 A/H1f(part) Cliffburn Road 4, Donaldsons Acre Arbroath Avonside Timber Frame Ltd COMP 0.20 6 ACA162 Westway Arbroath Guild Homes COMP 0.96 12 ACL023 Leysmill Farm Leysmill Linlathen Estates COMP 0.38 7 Forfar HMA SITEREF LOCAL NAME LOCATION DEVELOPER STATUS AREA TOTAL PLAN COMPLETIONS FKF085 F/H6 Lour Road, Beechhill House Forfar Kirkcare Housing Association COMP 0.64 16 FKF105 F/H12(part) Chapel Street 2 Forfar Angus HA COMP 0.11 6 FKK025 K/H1c Tannage Brae Kirriemuir Angus Housing Association COMP 0.16 13 FKK064 Golf Road, Northmuir Garage Kirriemuir J Hardie COMP 0.40 7 FKL003 L/H1a Dundee Road 2 Letham Angus HA/Webster Contracts COMP 0.20 9 FKL014 FKL/H1a Milton of Finavon Finavon F P C Construction COMP 1.40 18 FKL025 L/H1c West Hemming Street (Caravan Site) Letham G S Brown Construction COMP 0.60 19 FKL031 FKL/H1c Westbank 2, Heardhill Road Westmuir D A Mcmartin COMP 0.60 8 FKL148 L/H1d Guthrie Street East Letham Guild Homes COMP 0.65 14 FKL251 Gradonfield Westmuir Angus Housing Association COMP 0.21 6 Brechin/Montrose HMA SITEREF LOCAL NAME LOCATION DEVELOPER STATUS AREA TOTAL PLAN COMPLETIONS BRB016 Park Road, Viewbank Brechin Mr I -

The 6Th Duke of Athole: Chieftain, Landlord, Patriot and Mason Member No

The 6th Duke of Athole: Chieftain, Landlord, Patriot and Mason Member No. 1 on the roll of our Lodge is Bro. George Augustus Frederick John Murray, 6th Duke of Athole and Grand Master Mason of Scotland. That this Lodge is called The Athole Lodge is no coincidence. The founding fathers, or rather, brothers, of the Lodge were Bro. Dr. Donald Patrick Stewart and Bro. Duncan Walker, both of whom were Perthshire men. They had been at the centre of a dispute within the Kirkintilloch Lodge St John Kilwinning No. 28 and had decided that the best way to restore Masonic harmony to Kirkintilloch was to establish a new Lodge. Dr Stewart was known to the 6th Duke of Athole and, with his assistance, the Lodge was quickly established. There were no sponsor Lodges. The Grand Master Mason’s support was sufficient and he would have been gratified by the strong Athole identity that the new Lodge was to assume. George Augustus Frederick John Murray was born on 20 September 1814 in Great Cumberland Place, London. His father was James Murray, 1st Baron Glenlyon, brother of the 5th Duke of Atholl, and his wife, Lady Emily Frances Percy. On his father’s death in 1837, George Murray became 2nd Baron Glenlyon. In 1839, he married Anne Home- Drummond of Blair Drummond, near Stirling In 1846, John Murray, the 5th Duke, died at the age of 68. He had been declared insane in 1798, at the age of 20, and lived in seclusion for the rest of his life. George Murray, Lord Glenlyon, succeeded him as 6th Duke, being the nearest male relative. -

Blair Castle and Gardens Group Information 2019/20 Ancient Walls

Atholl Estates Blair Castle and Gardens Group Information 2019/20 Ancient Walls Step back in time with a visit to Blair Castle, the ancestral seat of the Dukes and Earls of Atholl. The castle dates to 1269 and has seen many changes and additions over ‘We were very time. Discover over 700 years of Scottish very sorry to leave history across 30 rooms, including the Blair and the dear Baronial Entrance Hall, State Dining Room Highlands!’ and the magnificent Ballroom bedecked in hundreds of antlers. QUEEN VICTORIA Learn how the castle has been transformed through the ages from its cold medieval beginnings to become a comfortable family home, how a visit from Queen Victoria led to the creation of Europe’s only private regiment, the Atholl Highlanders. Timeless Stories Our service to you. Over 19 generations, the Stewarts and We pride ourselves on the dedicated Murrays of Atholl have backed winners and service that we offer to group organisers, losers, fallen in and out of political favour, from enquiry to departure. As the first won battles and lost them. They have private home in Scotland to open to the almost all, in one way or another, left their Famous Jacobite public in 1936, we have a wealth of mark on Blair Castle. The story will take you commander Lord experience welcoming individuals and from Mary, Queen of Scots to the Civil War, George Murray larger groups through our doors. and from the Act of Union, to the Jacobite besieged Blair ‘Every little trifle cause and the disaster of Culloden, and Castle in 1746, All groups will receive an introduction to and every sport from the Isle of Man to Queen Victoria’s the last siege on the castle’s history by one of our guides I had become love affair with the Scottish Highlands and Scottish soil. -

Perth and Kinross Council Environment, Enterprise and Infrastructure Committee 3 6 September 2017

Securing the future • Improving services • Enhancing quality of life • Making the best use of public resources Council Building 2 High Street Perth PH1 5PH Thursday, 09 November 2017 A Meeting of the Environment, Enterprise and Infrastructure Committee will be held in the Council Chamber, 2 High Street, Perth, PH1 5PH on Wednesday, 08 November 2017 at 10:00 . If you have any queries please contact Committee Services on (01738) 475000 or email [email protected] . BERNADETTE MALONE Chief Executive Those attending the meeting are requested to ensure that all electronic equipment is in silent mode. Members: Councillor Colin Stewart (Convener) Councillor Michael Barnacle (Vice-Convener) Councillor Callum Purves (Vice-Convener) Councillor Alasdair Bailey Councillor Stewart Donaldson Councillor Dave Doogan Councillor Angus Forbes Councillor Anne Jarvis Councillor Grant Laing Councillor Murray Lyle Councillor Andrew Parrott Councillor Crawford Reid Councillor Willie Robertson Councillor Richard Watters Councillor Mike Williamson Page 1 of 294 Page 2 of 294 Environment, Enterprise and Infrastructure Committee Wednesday, 08 November 2017 AGENDA MEMBERS ARE REMINDED OF THEIR OBLIGATION TO DECLARE ANY FINANCIAL OR NON-FINANCIAL INTEREST WHICH THEY MAY HAVE IN ANY ITEM ON THIS AGENDA IN ACCORDANCE WITH THE COUNCILLORS’ CODE OF CONDUCT. 1 WELCOME AND APOLOGIE S 2 DECLARATIONS OF INTE REST 3 MINUTE OF MEETING OF THE ENVIRONMENT, ENT ERPRISE 5 - 10 AND INFRASTRUCTURE COMMITTEE OF 6 SEPTEMBER 2017 FOR APPROVAL AND SIGNATURE 4 PERTH CITY DEVELOPME NT