Military Law Review

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 968 Commencement of Criminal Proceedings

Updated 2019−20 Wis. Stats. Published and certified under s. 35.18. September 17, 2021. 1 Updated 19−20 Wis. Stats. COMMENCEMENT OF CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS 968.01 CHAPTER 968 COMMENCEMENT OF CRIMINAL PROCEEDINGS 968.01 Complaint. 968.28 Application for court order to intercept communications. 968.02 Issuance and filing of complaints. 968.29 Authorization for disclosure and use of intercepted wire, electronic or oral 968.03 Dismissal or withdrawal of complaints. communications. 968.04 Warrant or summons on complaint. 968.30 Procedure for interception of wire, electronic or oral communications. 968.05 Corporations or limited liability companies: summons in criminal cases. 968.31 Interception and disclosure of wire, electronic or oral communications 968.06 Indictment by grand jury. prohibited. 968.07 Arrest by a law enforcement officer. 968.32 Forfeiture of contraband devices. 968.073 Recording custodial interrogations. 968.33 Reports concerning intercepted wire or oral communications. 968.075 Domestic abuse incidents; arrest and prosecution. 968.34 Use of pen register or trap and trace device restricted. 968.08 Release by law enforcement officer of arrested person. 968.35 Application for an order for a pen register or a trap and trace device. 968.085 Citation; nature; issuance; release of accused. 968.36 Issuance of an order for a pen register or a trap and trace device. 968.09 Warrant on failure to appear. 968.37 Assistance in the installation and use of a pen register or trap and trace 968.10 Searches and seizures; when authorized. device. 968.11 Scope of search incident to lawful arrest. 968.373 Warrant to track a communications device. -

Investigation of a Criminal Offense Part 1: Initiation, Suspension, and Discontinuation of a Criminal Investigation General Commentary

153 Chapter 8: Investigation of a Criminal Offense Part 1: Initiation, Suspension, and Discontinuation of a Criminal Investigation General Commentary Under the MCCP, the initiation, suspension, and discontinuation of a criminal inves- tigation carry specific requirements to make them official. This is not the practice in every state around the world. In states that do require an official action, the require- ments are often based on a more strict interpretation of the principle of legality, entail- ing that each stage has a specific legal meaning. To initiate, suspend, or discontinue an investigation, one requirement is the issuance of a written decision, on which a high premium is placed in many states. The drafters of the Model Codes concluded that, in the context of the MCCP, a similarly high premium should be placed on both the prin- ciple of legality and the requirement of written decisions as a means of ensuring that the actions taken in the course of the investigation will be properly recorded. In many post-conflict states, investigation records have not been properly maintained and files have been lost. Consequently, a suspect could sit in detention awaiting trial while the office of the prosecutor and the prison have little or no information about the suspect. This problem could lead to a gross impingement of the suspect’s fundamental human rights, such as the right to trial without undue delay (Article 63), and inadvertently contribute to prison overcrowding, another feature of many post-conflict states. It is therefore imperative that significant attention be given to the issue of record keeping in the course of the criminal investigation. -

Cops Or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein

Georgia State University Law Review Volume 26 Article 5 Issue 2 Winter 2009 March 2012 Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police Dimitri Epstein Follow this and additional works at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Dimitri Epstein, Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute Applies to No-Knock Raids by Police, 26 Ga. St. U. L. Rev. (2012). Available at: https://readingroom.law.gsu.edu/gsulr/vol26/iss2/5 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Publications at Reading Room. It has been accepted for inclusion in Georgia State University Law Review by an authorized editor of Reading Room. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Epstein: Cops or Robbers? How Georgia's Defense of Habitation Statute App COPS OR ROBBERS? HOW GEORGIA'S DEFENSE OF HABITATION STATUTE APPLIES TO NONO- KNOCK RAIDS BY POLICE Dimitri Epstein*Epstein * INTRODUCTION Late in the fall of 2006, the city of Atlanta exploded in outrage when Kathryn Johnston, a ninety-two-year old woman, died in a shoot-out with a police narcotics team.team.' 1 The police used a "no"no- knock" search warrant to break into Johnston's home unannounced.22 Unfortunately for everyone involved, Ms. Johnston kept an old revolver for self defense-not a bad strategy in a neighborhood with a thriving drug trade and where another elderly woman was recently raped.33 Probably thinking she was being robbed, Johnston managed to fire once before the police overwhelmed her with a "volley of thirty-nine" shots, five or six of which proved fatal.fata1.44 The raid and its aftermath appalled the nation, especially when a federal investigation exposed the lies and corruption leading to the incident. -

Inter-American Court of Human Rights

INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS CASE OF FERNÁNDEZ PRIETO AND TUMBEIRO V. ARGENTINA JUDGMENT OF SEPTEMBER 1, 2020 (Merits and reparations) In the case of Fernández Prieto and Tumbeiro v. Argentina, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights (hereinafter “the Inter-American Court” or “the Court”), composed of the following judges:* Elizabeth Odio Benito, President L. Patricio Pazmiño Freire, Vice President Eduardo Vio Grossi, Judge Humberto Antonio Sierra Porto, Judge Eduardo Ferrer Mac-Gregor Poisot, Judge, and Ricardo Pérez Manrique, Judge, also present, Pablo Saavedra Alessandri, Secretary,** pursuant to Articles 62(3) and 63(1) of the American Convention on Human Rights (hereinafter “the American Convention” or “the Convention”) and Articles 31, 32, 42, 65 and 67 of the Rules of Procedure of the Court (hereinafter “the Rules of Procedure” or “ the Court’s Rules of Procedure”), delivers this judgment which is structured as follows: * Judge Eugenio Raúl Zaffaroni, an Argentine national, did not take part in the deliberation or signature of this judgment, in accordance with the provisions of Article 19(1) and (2) of the Court’s Rules of Procedure. ** The Deputy Secretary, Romina I. Sijniensky, did not participate in the processing of this case, or in the deliberation and signature of this judgment. TABLE OF CONTENTS I INTRODUCTION OF THE CASE AND PURPOSE OF THE DISPUTE 3 II PROCEEDINGS BEFORE THE COURT 4 III JURISDICTION 6 IV ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF RESPONSIBILITY 6 A. Observations of the parties and of the Commission 6 B. Considerations of the Court 7 V EVIDENCE 9 A. Admissibility of the documentary evidence 9 B. -

POLICING REFORM in AFRICA Moving Towards a Rights-Based Approach in a Climate of Terrorism, Insurgency and Serious Violent Crime

POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, Mutuma Ruteere & Simon Howell POLICING REFORM IN AFRICA Moving towards a rights-based approach in a climate of terrorism, insurgency and serious violent crime Edited by Etannibi E.O. Alemika, University of Jos, Nigeria Mutuma Ruteere, UN Special Rapporteur, Kenya Simon Howell, APCOF, South Africa Acknowledgements This publication is funded by the Ford Foundation, the United Nations Development Programme, and the Open Societies Foundation. The findings and conclusions do not necessarily reflect their positions or policies. Published by African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Copyright © APCOF, April 2018 ISBN 978-1-928332-33-6 African Policing Civilian Oversight Forum (APCOF) Building 23b, Suite 16 The Waverley Business Park Wyecroft Road Mowbray, 7925 Cape Town, ZA Tel: +27 21 447 2415 Fax: +27 21 447 1691 Email: [email protected] Web: www.apcof.org.za Cover photo taken in Nyeri, Kenya © George Mulala/PictureNET Africa Contents Foreword iv About the editors v SECTION 1: OVERVIEW Chapter 1: Imperatives of and tensions within rights-based policing 3 Etannibi E. O. Alemika Chapter 2: The constraints of rights-based policing in Africa 14 Etannibi E.O. Alemika Chapter 3: Policing insurgency: Remembering apartheid 44 Elrena van der Spuy SECTION 2: COMMUNITY–POLICE NEXUS Chapter 4: Policing in the borderlands of Zimbabwe 63 Kudakwashe Chirambwi & Ronald Nare Chapter 5: Multiple counter-insurgency groups in north-eastern Nigeria 80 Benson Chinedu Olugbuo & Oluwole Samuel Ojewale SECTION 3: POLICING RESPONSES Chapter 6: Terrorism and rights protection in the Lake Chad basin 103 Amadou Koundy Chapter 7: Counter-terrorism and rights-based policing in East Africa 122 John Kamya Chapter 8: Boko Haram and rights-based policing in Cameroon 147 Polycarp Ngufor Forkum Chapter 9: Police organizational capacity and rights-based policing in Nigeria 163 Solomon E. -

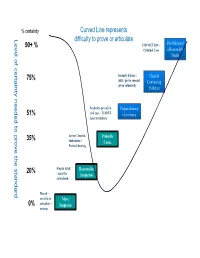

Level of Certainty Needed to Prove the Standard

% certainty Curved Line represents Level of certainty needed to prove the standard needed toprove of certainty Level difficulty to prove or articulate 90+ % CONVICTION – Proof Beyond Criminal Case a Reasonable Doubt 75% Insanity defense / Clear & alibi / prove consent Convincing given voluntarily Evidence Needed to prevail in Preponderance 51% civil case – LIABLE of evidence Asset Forfeiture 35% Arrest / Search / Probable Indictment / Cause Pretrial hearing 20% Stop & Frisk Reasonable – must be Suspicion articulated Hunch – not able to Mere 0% articulate / Suspicion no stop Mere Suspicion – This term is used by the courts to refer to a hunch or intuition. We all experience this in everyday life but it is NOT enough “legally” to act on. It does not mean than an officer cannot observe the activity or person further without making contact. Mere suspicion cannot be articulated using any reasonably accepted facts or experiences. An officer may always make a consensual contact with a citizen without any justification. The officer will however have not justification to stop or hold a person under this situation. One might say something like, “There is just something about him that I don’t trust”. “I can’t quit put my finger on what it is about her.” “He looks out of place.” Reasonable Suspicion – Stop, Frisk for Weapons, *(New) Search of vehicle incident to arrest under Arizona V. Gant. The landmark case for reasonable suspicion is Terry v. Ohio, 392 U.S. 1 (1968) This level of proof is the justification police officers use to stop a person under suspicious circumstances (e.g. a person peaking in a car window at 2:00am). -

Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure Dallin H

If you have issues viewing or accessing this file contact us at NCJRS.gov. Reprinted for private circulation from THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LAW REVIEW Vol. 37, No.4, Summer 1970 Copyright 1970 by the University of Chicago l'RINTED IN U .soA. Studying the Exclusionary Rule in Search and Seizure Dallin H. OakS;- The exclusionary rule makes evidence inadmissible in court if law enforcement officers obtained it by means forbidden by the Constitu tion, by statute or by court rules. The United States Supreme Court currently enforces an exclusionary rule in state and federal criminal, proceedings as to four major types of violations: searches and seizures that violate the fourth amendment, confessions obtained in violation of the fifth and' sixth amendments, identification testimony obtained in violation of these amendments, and evidence obtained by methods so shocking that its use would violate the due process clause.1 The ex clusionary rule is the Supreme Court's sole technique for enforcing t Professor of Law, The University of Chicago; Executive Director-Designate, The American Bar Foundation. This study was financed by a three-month grant from the National Institute of Law Enforcement and Criminal Justice of the Law Enforcement Assistance Administration of the United States Department of Justice. The fact that the National Institute fur nished financial support to this study does not necessarily indicate the concurrence of the Institute in the statements or conclusions in this article_ Many individuals assisted the author in this study. Colleagues Hans Zeisel and Franklin Zimring gave valuable guidance on analysis, methodology and presentation. Colleagues Walter J. -

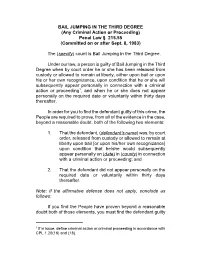

BAIL JUMPING in the THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action Or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on Or After Sept

BAIL JUMPING IN THE THIRD DEGREE (Any Criminal Action or Proceeding) Penal Law § 215.55 (Committed on or after Sept. 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Bail Jumping in the Third Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of Bail Jumping in the Third Degree when by court order he or she has been released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty, either upon bail or upon his or her own recognizance, upon condition that he or she will subsequently appear personally in connection with a criminal action or proceeding1, and when he or she does not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. In order for you to find the defendant guilty of this crime, the People are required to prove, from all of the evidence in the case, beyond a reasonable doubt, both of the following two elements: 1. That the defendant, (defendant’s name) was, by court order, released from custody or allowed to remain at liberty upon bail [or upon his/her own recognizance] upon condition that he/she would subsequently appear personally on (date) in (county) in connection with a criminal action or proceeding; and 2. That the defendant did not appear personally on the required date or voluntarily within thirty days thereafter. Note: If the affirmative defense does not apply, conclude as follows: If you find the People have proven beyond a reasonable doubt both of those elements, you must find the defendant guilty 1 If in issue, define criminal action or criminal proceeding in accordance with CPL 1.20(16) and (18). -

Washington and Saratoga Counties in the War of 1812 on Its Northern

D. Reid Ross 5-8-15 WASHINGTON AND SARATOGA COUNTIES IN THE WAR OF 1812 ON ITS NORTHERN FRONTIER AND THE EIGHT REIDS AND ROSSES WHO FOUGHT IT 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Illustrations Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown 3 Map upstate New York locations 4 Map of Champlain Valley locations 4 Chapters 1. Initial Support 5 2. The Niagara Campaign 6 3. Action on Lake Champlain at Whitehall and Training Camps for the Green Troops 10 4. The Battle of Plattsburg 12 5. Significance of the Battle 15 6. The Fort Erie Sortie and a Summary of the Records of the Four Rosses and Four Reids 15 7. Bibliography 15 2 Maj. Gen. Jacob Brown as depicted3 in an engraving published in 1862 4 1 INITIAL SUPPORT Daniel T. Tompkins, New York’s governor since 1807, and Peter B. Porter, the U.S. Congressman, first elected in 1808 to represent western New York, were leading advocates of a war of conquest against the British over Canada. Tompkins was particularly interested in recruiting and training a state militia and opening and equipping state arsenals in preparation for such a war. Normally, militiamen were obligated only for three months of duty during the War of 1812, although if the President requested, the period could be extended to a maximum of six months. When the militia was called into service by the governor or his officers, it was paid by the state. When called by the President or an officer of the U.S. Army, it was paid by the U.S. Treasury. In 1808, the United States Congress took the first steps toward federalizing state militias by appropriating $200,000 – a hopelessly inadequate sum – to arm and train citizen soldiers needed to supplement the nation’s tiny standing army. -

Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial

William & Mary Law Review Volume 37 (1995-1996) Issue 1 Article 10 October 1995 Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial Alan L. Adlestein Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr Part of the Criminal Law Commons Repository Citation Alan L. Adlestein, Conflict of the Criminal Statute of Limitations with Lesser Offenses at Trial, 37 Wm. & Mary L. Rev. 199 (1995), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr/vol37/iss1/10 Copyright c 1995 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmlr CONFLICT OF THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS WITH LESSER OFFENSES AT TRIAL ALAN L. ADLESTEIN I. INTRODUCTION ............................... 200 II. THE CRIMINAL STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS AND LESSER OFFENSES-DEVELOPMENT OF THE CONFLICT ........ 206 A. Prelude: The Problem of JurisdictionalLabels ..... 206 B. The JurisdictionalLabel and the CriminalStatute of Limitations ................ 207 C. The JurisdictionalLabel and the Lesser Offense .... 209 D. Challenges to the Jurisdictional Label-In re Winship, Keeble v. United States, and United States v. Wild ..................... 211 E. Lesser Offenses and the Supreme Court's Capital Cases- Beck v. Alabama, Spaziano v. Florida, and Schad v. Arizona ........................... 217 1. Beck v. Alabama-LegislativePreclusion of Lesser Offenses ................................ 217 2. Spaziano v. Florida-Does the Due Process Clause Require Waivability? ....................... 222 3. Schad v. Arizona-The Single Non-Capital Option ....................... 228 F. The Conflict Illustrated in the Federal Circuits and the States ....................... 230 1. The Conflict in the Federal Circuits ........... 232 2. The Conflict in the States .................. 234 III. -

Reasonable Cause Exists When the Public Servant Has

ESCAPE IN THE SECOND DEGREE Penal Law § 205.10(2) (Escape from Custody by Defendant Arrested for, Charged with, or Convicted of Felony) (Committed on or after September 8, 1983) The (specify) count is Escape in the Second Degree. Under our law, a person is guilty of escape in the second degree when, having been arrested for [or charged with] [or convicted of] a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony, he or she escapes from custody. The following terms used in that definition have a special meaning: CUSTODY means restraint by a public servant pursuant to an authorized arrest or an order of a court.1 "Public Servant" means any public officer or employee of the state or of any political subdivision thereof or of any governmental instrumentality within the state, [or any person exercising the functions of any such public officer or employee].2 [Add where appropriate: An arrest is authorized when the public servant making the arrest has reasonable cause to believe that the person being arrested has committed a crime. 3 Reasonable cause does not require proof that the crime was in fact committed. Reasonable cause exists when the public servant has 1 Penal Law §205.00(2). 2 Penal Law §10.00(15). 3 This portion of the charge assumes an arrest for a crime only as authorized by the provisions of CPL 140.10(1)(b). If the arrest was authorized pursuant to some other subdivision of CPL 140.10 or other law, substitute the applicable provision of law. knowledge of facts and circumstances sufficient to support a reasonable belief that a crime has been or is being committed.4 ] ESCAPE means to get away, break away, get free or get clear, with the conscious purpose to evade custody.5 (Specify the felony for which the defendant was arrested, charged or convicted) is a class C [or class D] [or class E] felony. -

Police-Media Relations

0EASTHAMPTON POLICE Department Manual: DEPARTMENT Policy No. 1.08 Subject: Searches & Seizures MASSACHUSETTS POLICE ACCREDITATION GENERAL ORDER STANDARDS REFERENCED: 1.2.4, a, b, c, d, e, f, g; 74.3.1 M.G.L. Chapter 276 Section 2D (12/21/20) Issue Date: 01-17- Issuing Authority 2021 Robert J. Alberti Effective Date: 01- Robert J. Alberti 27-2021 Chief of Police I. General Considerations and Guidelines: The term “searches and seizures” includes the examination of persons or places for the discovery of contraband, property stolen or otherwise unlawfully obtained or held, or of evidence of the commission of crime, and the taking into legal custody of such property or evidence for presentation to the court. Failure to comply with the legal technicalities which govern these procedures results in more failures to obtain convictions than any other source. The Fourth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution has been interpreted by the U.S. Supreme Court to require that, whenever possible and practicable, with certain limited exceptions, a police officer should always obtain a valid search warrant in advance.1 The Fourth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution provides as follows: The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated, and no Warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched, and the persons or things to be seized. Page 1 Article XIV of the Massachusetts Constitution provides as follows: Every subject has a right to be secure from all unreasonable searches, and seizures, of his person, his houses, his papers, and all his possessions.