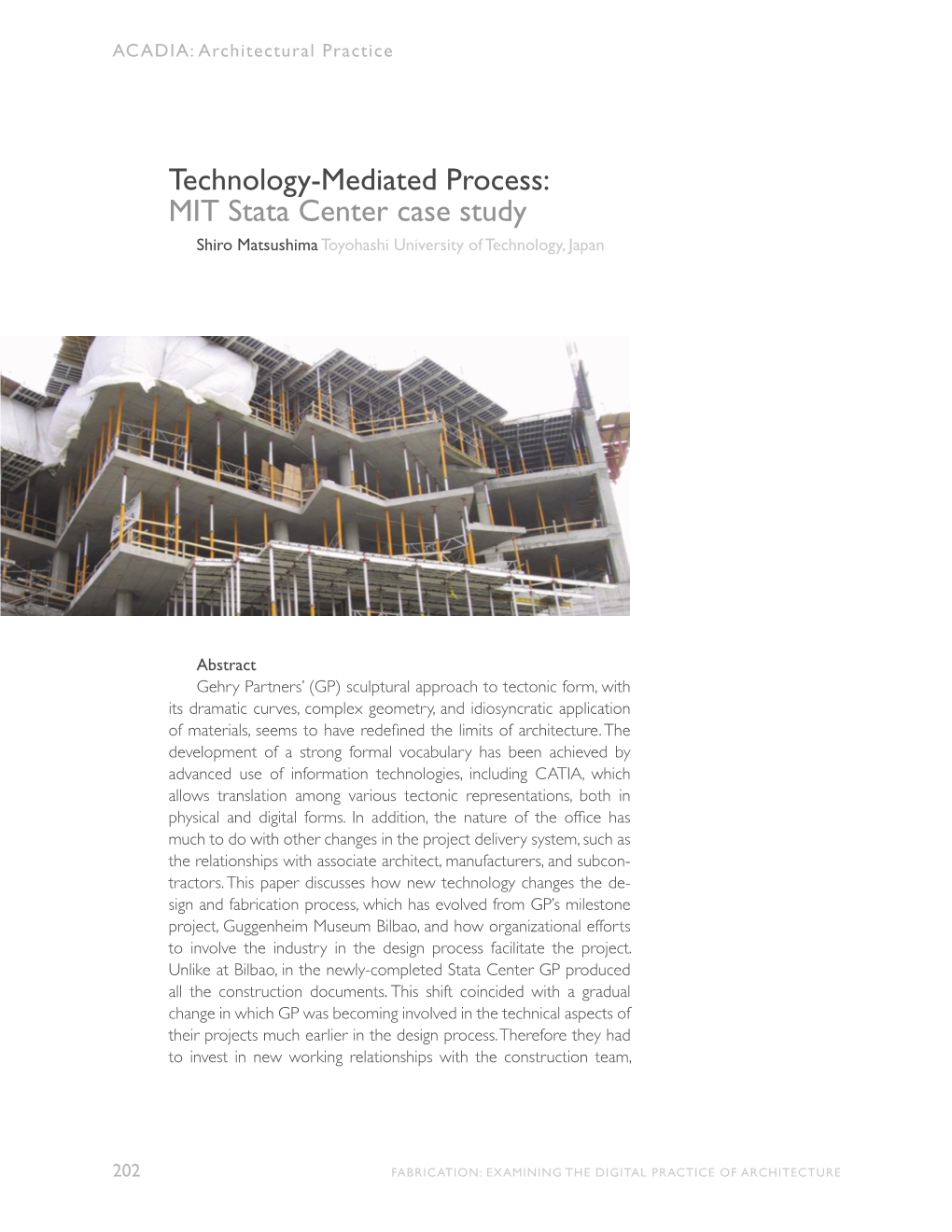

Technology-Mediated Process: MIT Stata Center Case Study Shiro Matsushima Toyohashi University of Technology, Japan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MIT Faculty Newsletter, Vol. XXIX No. 1, September/October 2016

Massachusetts Vol. XXIX No. 1 Institute of September/October 2016 Technology MITFaculty http://web.mit.edu/fnl Newsletter in this issue we offer commentary on the Faculty and Staff Quality of Life Survey (below and page 22); a report on MIT’s overall international activities, “Global MIT” (below) and “The MIT Haiti-Initiative” (page 14); and two articles on Access MIT (pages 16 and 18). 2016 Presidential Candidates Global MIT MIT Asked, We Editorial Answered: The 2016 Presidential Faculty Quality of Candidates Weigh In Life Survey On Science Policy Krishna Rajagopal, Leslie Kolodziejski, Issues R. K. Lester Christopher Capozzola THE MIT COMMUNITY IS magnifi- WELCOME BACK FROM WHAT we IN SEPTEMBER, PRESIDENTIAL cently but unselfconsciously multina- hope has been an invigorating summer, candidates Donald Trump, Hillary tional. With 42% of our faculty, 43% of and all best wishes for the new academic Rodham Clinton, and Jill Stein returned our graduate students, and 65% of our year. their responses to a set of 20 key science post-docs hailing from countries other The three of us have spent time over policy issues (Libertarian Party candidate than the U.S., and 151 countries repre- the summer diving into the results from Gary Johnson did not respond). The sented on our campus, MIT is truly “of the 2016 Faculty Quality of Life Survey. questionnaire was prepared by a national the world.” The outcome of the survey provides a science consortium, ScienceDebate.org, We are also, increasingly, in the world. wealth of information and insights about that included the American Association Today MIT faculty and students are the perspectives of the MIT Faculty on a for the Advancement of Science and the working in more than 75 countries, and wide variety of questions. -

Campusmap06.Pdf

A B C D E F MIT Campus Map Welcome to MIT #HARLES3TREET All MIT buildings are designated .% by numbers. Under this numbering "ROAD 1 )NSTITUTE 1 system, a single room number "ENT3TREET serves to completely identify any &ULKERSON3TREET location on the campus. In a 2OGERS3TREET typical room number, such as 7-121, .% 5NIVERSITY (ARVARD3QUARE#ENTRAL3QUARE the figure(s) preceding the hyphen 0ARK . gives the building number, the first .% -)4&EDERAL number following the hyphen, the (OTEL -)4 #REDIT5NION floor, and the last two numbers, 3TATE3TREET "INNEY3TREET .7 43 the room. 6ILLAGE3T -)4 -USEUM 7INDSOR3TREET .% 4HE#HARLES . 3TARK$RAPER 2ANDOM . 43 3IDNEY 0ACIFIC 3IDNEY3TREET (ALL ,ABORATORY )NC Please refer to the building index on 0ACIFIC3TREET .7 .% 'RADUATE2ESIDENCE 3IDNEY 43 0ACIFIC3TREET ,ANDSDOWNE 3TREET 0ORTLAND3TREET 43 the reverse side of this map, 3TREET 7INDSOR .% ,ANDSDOWNE -ASS!VE 3TREET,OT .7 3TREET .% 4ECHNOLOGY if the room number is unknown. 3QUARE "ROADWAY ,ANDSDOWNE3TREET . 43 2 -AIN3TREET 2 3MART3TREET ,ANDSDOWNE #ROSS3TREET ,ANDSDOWNE 43 An interactive map of MIT 3TREETGARAGE 3TREET 43 .% 2ESIDENCE)NN -C'OVERN)NSTITUTEFOR BY-ARRIOTT can be found at 0ACIFIC "RAIN2ESEARCH 3TREET,OT %DGERTON (OUSE 'ALILEO7AY http://whereis.mit.edu/. .7 !LBANY3TREET 0LASMA .7 .7 7HITEHEAD !LBANY3TREET )NSTITUTE 0ACIFIC3TREET,OT 3CIENCE .7 .! .!NNEX,OT "RAINAND#OGNITIVE AND&USION 0ARKING'ARAGE Parking -ASS 3CIENCES#OMPLEX 0ARSONS .% !VE,OT . !LBANY3TREET #ENTER ,ABORATORY "ROAD)NSTITUTE 'RADUATE2ESIDENCE .UCLEAR2EACTOR ,OT #YCLOTRON ¬ = -

Campus Map, Shuttle Routes & Parking

CAMPUS MAP, SHUTTLE ROUTES & PARKING SHUTTLE STOPS REUNION SHUTTLES SCHEDULE CAMPUS PARKING LOTS Tech Reunions Shuttle – red route Thursday, June 8 Saturday, June 10 and Sunday June 11 Four vehicles will service the Tech Reunions route (marked red on the map), All day: NW23 C, NW30 D, NW86 E, Waverly Lot F, All day: 158 Mass. Ave. Lot A, Albany Garage B, 1 Kresge/Maseeh Hall and one will service the MIT Museum route (marked blue on the map) the Westgate Lot (limited space) G, NW23 C, NW30 D, NW86 E, Waverly Lot F, 2 Burton House following hours: After 2:30 p.m.: West Lot H Westgate Lot G, West Lot H, West Garage I, 3 Westgate Parking Lot Kresge Lot J, Tang Center Lot (ungated lot) K Thursday, June 8: 2:00 p.m.–10:00 p.m. Friday, June 9 4 Hyatt Regency/W92 All day: NW23 C, NW30 D, NW86 E, Waverly Lot F, 5 Friday, June 9: 7:00 a.m.–7:30 p.m., then 11:00 p.m.–1:00 a.m. Parking for Registration and Check-in Simmons Hall G, *Please note that service to stops 1, 2, 3, 12, and 13 will be suspended from Westgate Lot (limited space) 20-minute parking is available in the Student Center 6 Johnson Athletics Center H, 9:00–10:30 a.m. for the Commencement procession. The MIT Museum Shuttle After 2:30 p.m.: West Lot West Garage I turnaround R1 , and in front of McCormick Hall R2 . Charles Street 7 Vassar Street at Mass Ave. -

Invisible Science

Invisible Science Steven Shapin here’s a McDonald’s restaurant near where I live in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Roughly equidistant from Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and close to one of the beating hearts of modern science and tech- Tnology, the restaurant sits across Massachusetts Avenue from a nondescript building full of entrepreneurial electronic gaming companies. Walk a little toward the MIT end of the avenue, and you pass major institutes for bioinformatics and cancer research, at least a dozen pharmaceutical and biotech companies, outposts of Microsoft and Google, the Frank Gehry−designed Stata Center, which houses much of MIT’s artifi- cial intelligence and computer science activities (with an office for Noam Chomsky), and several “workbars” and “coworking spaces” for start-up high-tech companies. You might think that this McDonald’s is well placed to feed the neighborhood’s scientists and engineers, but few of them actually eat there, perhaps convinced by sound sci- entific evidence that Big Macs aren’t good for them. (Far more popular among the scientists and techies is an innovative vegetarian restaurant across the street—styled as a “food lab”—founded, appropriately enough, by an MIT materials science and Harvard Business School graduate.) You might also assume that, while a lot of science happens at MIT and Harvard, and at the for-profit and nonprofit organizations clustered around the McDonald’s, the fast-food outlet itself has little or no significance for the place of science in late modern society. No scientists or engineers (that I know of) work there, and no scientific inquiry (that I am aware of) is going on there. -

J. Fiona Ragheb, Editor Essays by Jean-Louis Cohen, Beatriz Colomina, Mildred Friedman, William Mitchell, And}. Fiona Ragheb

TECT J. Fiona Ragheb, editor essays by Jean-Louis Cohen, Beatriz Colomina, Mildred Friedman, William Mitchell, and}. Fiona Ragheb GuggenheimMUSEUM FRANK GEHRY, ARCHITECT n A Personal Reflection Thomas Krens Selected Projects J. Fiona Ragheb and Kara Vander Weg 20 Davis Studio and Residence, 1968-72 24 Easy Edges Cardboard Furniture, 1969-73 28 Gehry Residence, 1977-78; 1991-92 40 Wagner Residence (unbuilt), 1978 42 Familian Residence (unbuilt), 1978 44 Loyola Law School, 1978- 54 Indiana Avenue Studios, 1979-81 56 Experimental Edges Cardboard Furniture, 1979-82 60 Aerospace Hall, California Science Center, 1982-84 64 Norton Residence, 1982-84 70 Winton Guest House, 1983-87 80 Fish and Snake Lamps, 1983-86 84 Sirmai-Peterson Residence, 1983-88 88 Edgemar Development, 1984-88 94 Chiat Day Building, 1985-91 702 Schnabel Residence, 1986-89 170 Vitra International Manufacturing Facility and Design Museum, 1987-89 778 Team Disneyland Administration Building, 1987-96 122 Vitra International Headquarters, 1988-94 726 Bent Wood Furniture Collection, 1989-92 130 Frederick R. Weisman Art Museum at the University of Minnesota, 1990-93 138 Fish Sculpture at Vila Olimpica, 1989-92 142 EMR Communication and Technology Center, 1991-95 148 Lewis Residence (unbuilt), 1989-95 760 Guggenheim Museum Bilbao, 1991-97 174 Nationale-Nederlanden Building, 1992-96 182 Goldstein Sud Housing, 1991-96 784 Vontz Center for Molecular Studies, University of Cincinnati, 1993-99 188 Walt Disney Concert Hall, 1987- 202 Der Neue Zollhof, 1994-99 212 DG Bank Building, 1995-2001 222 Experience Music Project (EMP), 1995-2000 234 Millennium Park Music Pavilion and Great Lawn, 1999- 236 Cond6 Nast Cafeteria, 1996-2000 244 Performing Arts Center at Bard College, 1997— 248 Peter B. -

MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2Nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected]

2014–2015 A GUIDE FOR PARENTS produced by in partnership with For more information, please contact MIT Parents Association 600 Memorial Drive W98-2nd FL Cambridge, MA 02139 (617) 253-8183 [email protected] Photograph by Dani DeSteven About this Guide UniversityParent has published this guide in partnership with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with the mission of helping you easily contents Photograph by Christopher Brown navigate your student’s university with the most timely and relevant information available. Discover more articles, tips and local business information by visiting the online guide at: www.universityparent.com/mit MIT Guide The presence of university/college logos and marks in this guide does not mean the school | Comprehensive advice and information for student success endorses the products or services offered by advertisers in this guide. 6 | Welcome to MIT 2995 Wilderness Place, Suite 205 8 | MIT Parents Association Boulder, CO 80301 www.universityparent.com 10 | MIT Parent Giving Top Five Reasons to Join Advertising Inquiries: 11 | (855) 947-4296 12 | 100 Things to Do before Your Student Graduates MIT [email protected] 20 | Academics Top cover photo by Christopher Harting. 21 | Resources for Academic Success 22 | Supporting Your Student 24 | Campus Map 27 | Department of Athletics, Physical Education, and Recreation 28 | MIT Police and Campus Safety SARAH SCHUPP PUBLISHER 30 | Housing MARK HAGER DESIGN MIT Dining 32 | MICHAEL FAHLER AD DESIGN 33 | Health Care What to Do On Campus Connect: 36 | 39 | Navigating MIT facebook.com/UniversityParent 41 | Academic Calendar MIT Songs twitter.com/4collegeparents 43 | 45 | Contact Information © 2014 UniversityParent Photo by Tom Gearty 48 | MIT Area Resources 4 Massachusetts Institute of Technology 5 www.universityparent.com/mit 5 MIT is coeducational and privately endowed. -

Boston College

Welcome to Boston and Cambridge We are so pleased that you are joining us for AUA 2013, the 58th gathering of the Association of University Architects. And we welcome you to our campuses. In addition to BC and MIT, we will be spending a day at Harvard, home to one of our new members. These three institutions could not be more different from one another and we look forward to sharing them all with you. Our Program Committee has assembled a lineup of tours, including the three campuses, case stud- ies, and (a lot of!) new member presentations. Our theme “Space: The Final Frontier” will be mani- fested through the panel discussions and various presentations we have organized. Yes, we are somewhat of a sports town, but it won’t be For those of you who have been to the Boston area, all sports, all the time. We have some great museums, welcome back! For those of you who have never been music venues, a variety of boat tours and numerous here, we are looking forward to sharing our very special opportunities to just hang out by the water…or in a city with you. It is a great place to live, to go to school park…or at a sidewalk café…or whatever. and to visit and we have provided some suggestions for things to do with your spare time. We are especially We thank you for joining us and hope that you find this pleased that we could arrange for an evening at our conference an exceptionally rewarding experience. -

Town Gown Report MIT MIT.NANO FACILITY / 6901-00 to the City of Cambridge

Town Gown Report MIT MIT.NANO FACILITY / 6901-00 to the City of Cambridge EXTERIOR ART VIEW TO EAST 11.18.14 2014 Town Gown Report to the City of Cambridge 2013-2014 Term (7/1/13 - 6/30/14) Submitted December 15, 2014 I. Existing Conditions 1 A. Faculty & Staff 1 B. Student Body 2 C. Student Residences 3 D. Facilities & Land Owned 4 E. Real Estate Leased 6 F. Payments to City of Cambridge 6 G. Institutional Shuttle Information 7 II. Future Plans Narrative 8 A. Moving Ideas into Action 8 B. Capital Planning, Renewal and Comprehensive Stewardship 12 C. MIT Students, Faculty, and Staff 12 D. Housing 13 E. Looking Ahead at MIT Planning & Development 15 F. Transportation 18 G. Sustainability 19 III. List of Projects 21 A. Completed in Reporting Period 21 B. In Construction 21 C. In Planning & Design 23 IV. Mapping Requirements 24 Map 1: MIT Property in Cambridge 25 Map 1a: MIT Buildings by Use 26 Map 2: MIT Projects 27 Map 3: Future Development Opportunities 28 Map 4: MIT Shuttle Routes 29 Map 5: MIT LEED Certified Buildings 30 Map 6: MIT Energy Efficiency Upgrade Projects 31 V. Transportation Demand Management 32 A. Commuting Mode of Choice 32 B. Point of Origin for Commuter Trips to Cambridge 32 C. TDM Strategy Updates 33 VI. Institution Specific Information Requests 34 Town Gown Report to the City of Cambridge 2013-2014 Term (7/1/13 - 6/30/14) Submitted December 15, 2014 I. Existing Conditions A. Faculty & Staff 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2024 (projected) Cambridge-based Staff 9,000- Head Count 8,857 8,893 9,124 9,329 9,692 10,000 FTEs 7,461 7,483 7,707 7,954 8,294 Post-Doctoral Staff 1 1,402 1,421 Cambridge-based Faculty Head Count 1,012 1,002 1,003 1,007 1,012 ~1,100 FTEs 1,009 997 997 1,002 1,005 Number of Cambridge Residents Employed at Cambridge 2,170 2,258 2,359 2,305 2,347 ~2,400 Facilities 1 1 Post-Doctorals are classified as staff and included in the headcount for Cambridge-based Staff. -

MIT News Digest 2013-2014

MIT News Digest 2013-2014 For the members of the Educ a tional Council Office of the Educational Council MITAdmissions MIT named three longtime faculty members to important academic posts. Cynthia Barnhart SM '86, PhD '88, Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Associate Dean of the School of Engineering, was named Chancellor. Martin Schmidt SM '83, PhD '88, Professor of Electrical Engineering and former Associate Provost, was named Provost. Michael Sipser was named Dean of the School of Science. Sipser has been the Barton L. Weller Professor of Mathematics and head of the Department of Mathematics for ten years. Provost Schmidt and Chancellor Barnhar MIT faculty and alumni continue to receive top Photo: Dominick Reuter accolades. Two MIT faculty members were named 2013 MacArthur Fellows. The first, Sara Seager, Joint Professor in the Department of Earth, Atmospheric, and Planetary Science and the Department of Physics, was honored in recognition for her work on exoplanets (planets outside the solar system). The second, Dina Katabi SM '99, PhD '03, is a professor in the Department of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, and was recognized for her work on wireless data transmission. Alumnus Robert Shiller SM '68, PhD '72 won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences, and former faculty member James Rothman won the 2013 Nobel Prize in Medicine. There are now 80 Nobel Laureates and 43 MacArthur Fellows with a connection to MIT. Alan Guth '68, SM '69, PhD '72, Victor F. Weisskopf Professor of Physics and MacVicar Faculty Fellow, won the 2014 Kavli Prize in Astrophysics for pioneering the theory of cosmic inflation. -

Constructs Fall 2008 Table of Contents 02 Charles Gwathmey

Constructs Yale Architecture Fall 2008 Constructs Fall 2008 Table of Contents 02 Charles Gwathmey and Robert A.M. Stern discuss Paul Rudolph Hall 04 Chuck Atwood and David Schwarz 06 Francisco Mangado 07 Frank Gehry’s Unbuilt Projects 08 Spring Event Reviews: Sustainable Architecture: Today and Tomorrow by Susan Yelavich and Daniel Barber 10 Modernism Events by Peggy Deamer and Joan Ockman 10 Building the Future by Jayne Merkel 12 Kroon Hall lectures Mobile Anxieties, the MED Symposium 13 In the Field: A New Urbanism by Tim Love Australia Symposium by Brigitte Shim New Zealand Symposium by Peggy Deamer 16 Book Reviews: Tim Culvahouse’s TVA Peter EIsenman’s Ten Canonical Buildings Hawaiian Modern Perspecta 40 Monster 18 Fall Events: Model City: Buildings and Projects by Paul Rudolph Hawaiian Modern Yale in Jordan YSoA Books 20 Spring 2008 Lectures 22 Spring 2008 Advanced Studios 24 Faculty News Herman Spiegel: An Appreciation 26 Alumni News Eugene Nalle: A Tribute 02 CONSTRUCTS YALE ARCHITECTURE FALL 2008 INTERVIEW: CHARLES GWATHMEY & ROBERT A.M. STERN Charles Gwathmey & Robert A.M. Stern A discussion Rudolph Hall), which between Dean will be rededicated Robert A.M. Stern on November 8, (’65) and Charles 2008, and the Gwathmey (’62) took opening of the new place this summer art history building, for Constructs on the Jeffrey Loria the occasion of the Center for the History renovation of the of Art. A&A Building (Paul Robert Stern When I became the plan was the Art Gallery’s need to expand dean in 1998, I set out to define our goals into the Swartwout Building and Street Hall. -

Campus Walking Tour

(O) MIT Museum O 265 Massachusetts Avenue NE25 M a 36 M L s 51 s a c h 39 38 76 u 32 MIT Chapel (Building W15). You are welcome to enter the non-denominational Chapel unless it is MIT Media Lab (Building E14) and List Visual Arts Center (Building E15). The Media Lab s e t t 37 s being used for a service or function. The Chapel was designed by renowned architect Eero Saarinen in contains more than 25 research groups working on 350+ projects that range from neuroengineering to A 35 v Campus e NE20 ssar Str W33 Va eet n 1955. Inside, a metal altarpiece created by legendary sculptor Harry Bertoia is used to scatter light that how children learn to developing the city car of the future. The first floor is open to visitors. u e enters the space from the beautiful domed skylight. 33 24 E19 The List Visual Arts Center, MIT’s contemporary art museum, collects, commissions, and presents 31 M W31 ain Fun Fact: The Chapel features a 1,300-pound bell cast at MIT’s Merton C. Flemings Metals provocative, artist-centric projects that engage MIT and the global arts community. The List is free and 17 26 K Stre Walking Tour W32 68 et Processing Laboratory. open to the public. For more information visit listart.mit.edu. B E18 W35 9 12 North Court 13 N E17 Fun Fact: The List has a Campus Loan Art Program and makes artwork from their permanent Welcome to MIT! 54 E25 Kendall/MIT W20 66 Red Line Hart Nautical Gallery of the MIT Museum (Building 1, through the doorway at 33 Mass. -

Kendall Square Final Report 2013

KENDALL SQUARE FINAL REPORT 2013 Cambridge Community Development Department 344 Broadway, Cambridge, MA 02139 617-349-4600 www.cambridgema.gov/cdd CREDITS EXECUTIVE OFFICE Richard C. Rossi, City Manager Lisa Peterson, Deputy City Manager CITY COUNCIL Henrietta Davis, Mayor E. Denise Simmons, Vice Mayor Leland Cheung Marjorie C. Decker Craig A. Kelley David P. Maher Kenneth E. Reeves Timothy J. Toomey, Jr. Minka vanBeuzekom PLANNING BOARD Hugh Russell, Chair H. Theodore Cohen Steve Cohen Catherine Preston Connolly Ahmed Nur Tom Sieniewicz Steven Winter Pamela Winters Thomas Anninger (retired 2013) William Tibbs (retired 2013) KENDALL SQUARE ADVISORY COMMITTEE: 2011 Olufolakemi Alalade Resident Viola Augustin Resident Barbara Broussard Resident Kelley Brown MIT, Campus Planning Michael Cantalupa Boston Properties Peter Calkins Forest City Conrad Crawford Resident Brian Dacey Cambridge Innovation Center Elizabeth Dean-Clower Resident Robert Flack Twining Properties Mark Jacobson Charles River Canoe and Kayak Jeff Lockwood Novartis Joe Maguire Alexandria Real Estate Maureen McCaffrey MIT Investment Management Company Travis McCready Kendall Square Association Peter Reed Ambit Creative Helen Rose Resident Brian Spatocco Resident Dylan Tierney Resident Joe Tulimieri Cambridge Redevelopment Authority (retired 2012) 3 CITY STAFF CONSULTANT TEAM Community Development Department K2C2 Planning Study Brian Murphy, Assistant City Manager Goody Clancy Cassie Arnaud Nelson Nygaard Chris Basler Carol R. Johnson Associates Roger Boothe MJB Consulting John