View the Online Friday Feature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

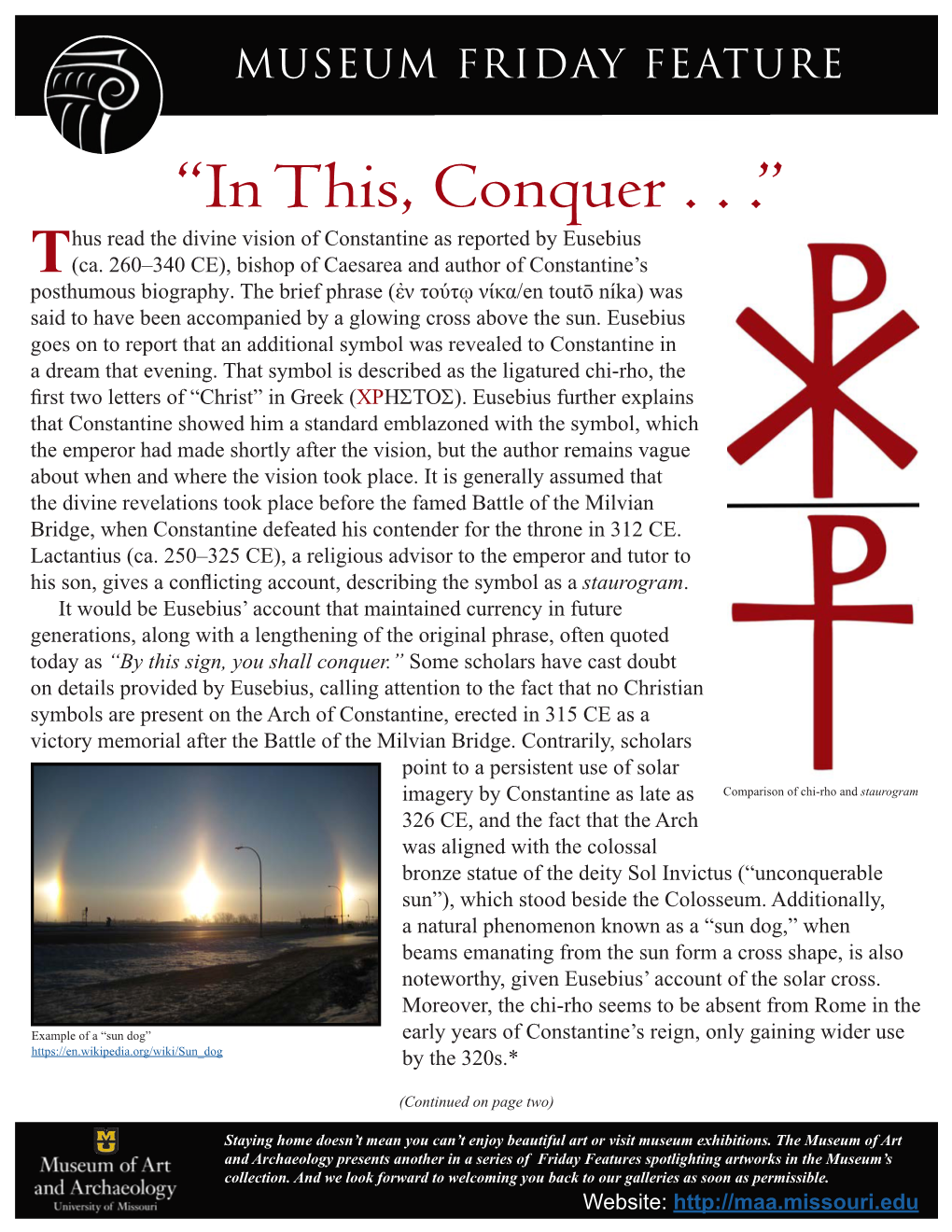

Sign of the Son of Man.”

Numismatic Evidence of the Jewish Origins of the Cross T. B. Cartwright December 5, 2014 Introduction Anticipation for the Jewish Messiah’s first prophesied arrival was great and widespread. Both Jewish and Samaritan populations throughout the known world were watching because of the timeframe given in Daniel 9. These verses, simply stated, proclaim that the Messiah’s ministry would begin about 483 years from the decree to rebuild Jerusalem in 445BC. So, beginning about 150 BC, temple scribes began placing the Hebrew tav in the margins of scrolls to indicate those verses related to the “Messiah” or to the “Last Days.” The meaning of the letter tav is “sign,” “symbol,” “promise,” or “covenant.” Shortly after 150 BC, the tav (both + and X forms) began showing up on coins throughout the Diaspora -- ending with a flurry of the use of the symbol at the time of the Messiah’s birth. The Samaritans, in an effort to remain independent of the Jewish community, utilized a different symbol for the anticipation of their Messiah or Tahib. Their choice was the tau-rho monogram, , which pictorially showed a suffering Tahib on a cross. Since the Northern Kingdom was dispersed in 725 BC, there was no central government authority to direct the use of the symbol. So, they depended on the Diaspora and nations where they were located to place the symbol on coins. The use of this symbol began in Armenia in 76 BC and continued through Yeshua’s ministry and on into the early Christian scriptures as a nomina sacra. As a result, the symbols ( +, X and ) were the “original” signs of the Messiah prophesied throughout scriptures. -

FRATERNITY INSIGNIA the Postulant Pin Signifies to The

FRATERNITY INSIGNIA The Postulant pin signifies to the campus that a man has affiliated himself with Alpha Chi Rho. The symbol which appears on the pin is called the Labarum. It is a symbol that is made up of the Greek letters Chi and Rho. The Postulant pin is to be worn over your heart. A good way to remember the proper placement of the pin is to count three buttons down from the collar (of a dress shirt, for example) and three finger widths to the left of the button. Never wear your Postulant pin on the lapel of a jacket; keep it close to the heart. The same rules apply to the Brother's badge that a man receives upon initiation into Alpha Chi Rho. The Roman Emperor, Constantine, like most Romans, did not believe in Christianity. However, historians say that Constantine saw a Labarum in the sky on the night before a battle. He had the symbol placed on banners and shields, then recorded a furious victory over his foe. Constantine then converted to Christianity and made the Labarum the symbol of the Imperial Roman Army. Alpha Chi Rho makes use of two forms of the Labarum. The ancient form of the Labarum is the chief public form of the Fraternity. In addition to the postulant pin, the Labarum appears predominately on the Fraternity ensign (flag). The other form of the Labarum, its modified configuration, is very significant to the Ritual of the Fraternity. Also, it is the form used on the Brother's badge. The badge is made up of a modified Labarum mounted on an oval. -

14. Tree of Life

What is a mosaic? Masolino da Panicale Who? It is a picture or pattern produced 1. Who painted the Tree of Life? by arranging together small pieces of stone, tile, glass, etc. 2. What is the purpose of the painting? The central image is one of (What key ideas does it convey?) Christ on the cross, but an 3. Where is the painting displayed? Alpha & What is an apse? What? interesting feature of this Omega 4. What is an apse? piece of art is that there are Chi-Rho An area with curved walls and a 5. What is a mosaic? many other symbolic images domed roof at the end of a church. surrounding the main frame. The Apostles The Apostles Areas to Discuss 1. Create a detailed mind-map (try to make this 1. The Alpha & Omega visual) When? Twelfth Century. 2. Chi-Rio Cross Doves 2. Create a multiple-choice quiz (aim for at least 3. The twelve apostles The 10 questions) 4. The lamb Twelve 3. Create a poster/leaflet Apostles 5. The doves Tree of life The Lamb (Jesus) 6. The four evangelists 7. The cross San Clemente church 8. The tree of life Where? in Rome 9. The Vine c) Explain the rich Christian symbolism that you will find in the Tree Of Life Apse The Twelve Apostles mosaic. [8] To depict the following: The Lamb 1. God is the first and the last. • There is reference made to the twelve Apostles who were specially chosen by 2. The battle against evil is won by the Cross of Christ. -

THE ETERNAL KINGDOM Lesson #40 December 25, 2019

THE ETERNAL KINGDOM Lesson #40 December 25, 2019 Intro: If you have been a part of this class, you are well aware of the book we have been studying. It is the Eternal Kingdom (show book and author; ask if everyone has a copy). As we continue to look at the departure from New Testament doctrine, we come to the topic of asceticism and celibacy. That can be found on the bottom of page 120 in your book. 1 DEPARTURE IN MANNER OF LIFE (ASCETICISM AND CELIBACY) • What sect encourage Christians to practice asceticism and celibacy? • Which bishop from Alexandria defended marriage as being proper, and who did he reference as an example of marriage? • What kind of communities came into existence as a result of this belief? Bullet 1: Gnostics. Bullet 2: Clement of Alexandria. He referenced the Apostle Peter as being a married man, he also said Paul was married based upon (Php.4:3). After reading Php.4:3, one would be very hard pressed to conclude that Paul was married. He was surrounded by women who were true servants and he acknowledged them, and (Rom.16:1-2) is a prime example. Bullet 3: Monastic communities. “Be safe, Be celibate” would have been their mantra. I’m reminded of Paul’s words in 1Tim.4:1-3 (read). 2 EASTER CELEBRATION • The church felt like it was in competition with their Jewish and pagan neighbors, and this gave way the establishment of religious holidays as a way to appeal to others. Easter came into existence. • Who did the church in Asia Minor claim that Easter was to coincide with the Passover? • Who supposedly taught the church in Rome that Easter occurred on a Sunday? • Who can find in the Bible a formal Easter celebration promoted by any apostle? (Read bullet 1). -

Christian Cruciform Symbols and Magical Charaktères Luc Renaut

Christian Cruciform Symbols and Magical Charaktères Luc Renaut To cite this version: Luc Renaut. Christian Cruciform Symbols and Magical Charaktères. Polytheismus – Monotheismus : Die Pragmatik religiösen Handelns in der Antike, Jun 2005, Erfurt, Germany. hal-00275253 HAL Id: hal-00275253 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-00275253 Submitted on 24 Apr 2008 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. CHRISTIAN CRUCIFORM SYMBOLS victory in Milvius Bridge, Constantine « was directed in a dream to cause AND MAGICAL CHARAKTÈRES the heavenly sign of God ( caeleste signum Dei ) to be delineated on the Communication prononcée dans le cadre du Colloque Polytheismus – Mono- shields of his soldiers, and so to proceed to battle. He does as he had been theismus : Die Pragmatik religiösen Handelns in der Antike (Erfurt, Philo- commanded, and he marks on the shields the Christ[’s name] ( Christum in sophische Fakultät, 30/06/05). scutis notat ), the letter X having been rotated ( transversa X littera ) and his top part curved in [half-]circle ( summo capite circumflexo ). »4 This As everyone knows, the gradual political entrance of Christian caeleste signum Dei corresponds to the sign R 5. -

{DOWNLOAD} Cross

CROSS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK James Patterson | 464 pages | 29 Apr 2010 | Headline Publishing Group | 9780755349401 | English | London, United Kingdom Cross Pens for Discount & Sales | Last Chance to Buy | Cross The Christian cross , seen as a representation of the instrument of the crucifixion of Jesus , is the best-known symbol of Christianity. For a few centuries the emblem of Christ was a headless T-shaped Tau cross rather than a Latin cross. Elworthy considered this to originate from Pagan Druids who made Tau crosses of oak trees stripped of their branches, with two large limbs fastened at the top to represent a man's arm; this was Thau, or god. John Pearson, Bishop of Chester c. In which there was not only a straight and erected piece of Wood fixed in the Earth, but also a transverse Beam fastened unto that towards the top thereof". There are few extant examples of the cross in 2nd century Christian iconography. It has been argued that Christians were reluctant to use it as it depicts a purposely painful and gruesome method of public execution. The oldest extant depiction of the execution of Jesus in any medium seems to be the second-century or early third-century relief on a jasper gemstone meant for use as an amulet, which is now in the British Museum in London. It portrays a naked bearded man whose arms are tied at the wrists by short strips to the transom of a T-shaped cross. An inscription in Greek on the obverse contains an invocation of the redeeming crucified Christ. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. -

Saints, Signs Symbols

\ SAINTS, SIGNS and SYMBOLS by W. ELLWOOD POST Illustrated and revised by the author FOREWORD BY EDWARD N. WEST SECOND EDITION CHRIST THE KING A symbol composed of the Chi Rho and crown. The crown and Chi are gold with Rho of silver on a blue field. First published in Great Britain in 1964 Fourteenth impression 1999 SPCK Holy Trinity Church Acknowledgements Marylebone Road London NW1 4DU To the Rev. Dr. Edward N. West, Canon Sacrist of the Cathedral Church of St. John the Divine, New York, who has © 1962, 1974 by Morehouse-Barlow Co. graciously given of his scholarly knowledge and fatherly encouragement, I express my sincere gratitude. Also, 1 wish to ISBN 0 281 02894 X tender my thanks to the Rev. Frank V. H. Carthy, Rector of Christ Church, New Brunswick, New Jersey, who initiated my Printed in Great Britain by interest in the drama of the Church; and to my wife, Bette, for Hart-Talbot Printers Ltd her loyal co-operation. Saffron Walden, Essex The research material used has been invaluable, and I am indebted to writers, past and contemporary. They are: E. E. Dorling, Heraldry of the Church; Arthur Charles Fox-Davies, Guide to Heraldry; Shirley C. Hughson of the Order of the Holy Cross, Athletes of God; Dr. F. C. Husenbeth Emblems of Saints; C. Wilfrid Scott-Giles, The Romance of Heraldry; and F. R. Webber, Church Symbolism. W. ELLWOOD POST Foreword Contents Ellwood Post's book is a genuine addition to the ecclesiological library. It contains a monumental mass of material which is not Page ordinarily available in one book - particularly if the reader must depend in general on the English language. -

The Other Symbols

The Other Symbols Monograms Alpha And Omega: These are the first and last letters of the Greek alphabet, signifying that Jesus Christ is the beginning and end of all things (Rev. 22:13). Chi Rho: This is a monogram of the first two letters X and P of the Greek word for Christ. Chi Rho with Alpha and Omega: This symbol for the Lord comes from the catacombs and indicates that he is the beginning, continuation and end of all things. Chi Rho with Alpha and Omega in a Circle: The symbol for Christ is within the symbol for eternity (the circle), thus signifying the eternal existence of the Savior. IHC or IHS: This is more often seen in Protestant churches and is almost as common as the Cross. They are the first three letters of the Greek word for Jesus. IHC is more ancient, but IHS is more common. I X: This symbol for the Lord consists of the initial letters of the Greek words for Jesus Christ. Jesus Christ The Victor: This is a Greek Cross with the abbreviated Greek words for Jesus Christ, the lines above the letters indicating that the words are abbreviated. The letters NIKA are translated victor or conqueror. I.N.R.I.: These are the initial letters for the Latin inscription on the Cross of the Crucified Christ. Iesus Nazaremus Rex Indaeorum: Jesus of Nazareth, King of the Jews (John 19:19). I.H.B.I [Greek] І.Н.Ц.І [Slavonic] Sun and Chi Rho: The sun is the source of light and Jesus is referred to as the Light (John 1:4). -

For Praying for Individuals Using the Ancient Christogram of Chi Rho

where world and worship meet creative idea for praying for individuals using the ancient Christogram of Chi Rho Chi and Ro describe the first two letters used to spell ‘Christ’ – which means the anointed one, or the special one – in Greek and have been used together as a symbolic/pictoral monogram to represent or abbreviate Christ since very early on in Christian history. We’ve found it provides an incredibly helpful way to visualise and pray into the presence, power and mercy of Christ over any given individual – whether they’re someone close to us or a public figure such as a church leader, politician or celebrity. There is something extraordinarily powerful about using something so ancient and global in its reach in new ways and to intercede about our own contemporary and specific contexts. You will need: tracing paper, a pencil, images of those you want to pray for (printed out or displayed on your device) 1. Hold and/or look at the image of the person you want to pray for, consciously lifting them and their situation and/or role to God. 2. Place the tracing paper over their image and begin by drawing an ‘X’ shaped ‘Chi’ over them with a pencil, imagining as you do so that you are praying the mercy of Christ over the totality of their person and life – physically, mentally, emotionally and spiritually. Originally it’s thought that the cross used here didn’t symbolise the crucifixion, which was generally pictured as a T shape, but you can still picture it as this – alongside perhaps the totality of every direction it implies. -

Crosses of the Red Cross of Constantine Presentation by P

Grand Imperial Conclave of the Masonic and Military Order of the Red Cross of Constantine, and the Orders of the Holy Sepulchre and of St. John the Evangelist for England and Wales and its Divisions and Conclaves Crosses of the Red Cross of Constantine Presentation by P. Kt. A. Briggs Div. Std. B.(C) and P. Kt. M.J. Hamilton Div. Warden of Regalia Warrington Conclave No. 206 November 16th 2011 INTRODUCTION Constantine's Conversion at the Battle of Milvian Bridge 312ad. MANY TYPES OF CROSSES These are just a few of the hundreds of designs of crosses THE RED CROSS • Red Cross of Constantine is the Cross Fleury - the most associated cross of the Order • With the Initials of the words ‘In Hoc Signo Vinces’ • Greek Cross (Cross Imissa – Cross of Earth • Light and Life Greek words for “light” and “life”. • Latin Cross THE VICTORS CROSS The Conqueror's or Victor's cross is the Greek cross with the first and last letters of "Jesus" and "Christ" on top, and the Greek word for conquerer, nika, on the bottom. • Iota (Ι) and Sigma (Σ) • I & C -The first and last letters of Jesus (ΙΗΣΟΥΣ). • X & C -The first and last letters of Christ (XPIΣTOΣ) The Triumphant Cross is a cross atop an orb. The cross represents Christianity and the orb (often with an equatorial band) represents the world. It symbolises Christ's triumph over the world, and prominent in images of Christ as Salvator Mundi - the Saviour of the World. THE CHI-RHO CROSS • The Chi-Rho emblem can be viewed as the first Christian Cross. -

Ancient Foundations Marshall High School Unit Five AD * How the Irish Saved Civilization

The Dark Ages Marshall High School Mr. Cline Western Civilization I: Ancient Foundations Marshall High School Unit Five AD * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • Ireland's Golden Age is closely tied with the spread of Christianity. • As Angles and Saxons began colonizing the old Roman province of Brittania, Christians living in Britain fled to the relative safety of Ireland. • These Christians found themselves isolated from their neighbors on the mainland and essentially cut off from the influence of the Roman Catholic Church. • This isolation, combined with the mostly agrarian society of Ireland, resulted in a very different form of Christianity. • Instead of establishing a centralized hierarchy, like the Roman Catholic Church, Irish Christians established monasteries. • Monasticism got an early start in Ireland, and monasteries began springing up across the countryside. • The Irish did not just build monasteries in Ireland. * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • They sent missionaries to England to begin reconverting their heathen neighbors. • From there they crossed the channels, accelerating the conversion of France, Germany and the Netherlands and establishing monasteries from Poitiers to Vienna. • These monasteries became centers of art and learning, producing art of unprecedented complexity, like the Book of Kells, and great scholars, like the Venerable Bede (Yes, the guy who wrote the Anglo Saxon History of Britain was indeed Irish!) * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art * How the Irish Saved Civilization • Christianity's Impact on Insular Art • Over time, Ireland became the cultural and religious leader of Northwestern Europe.