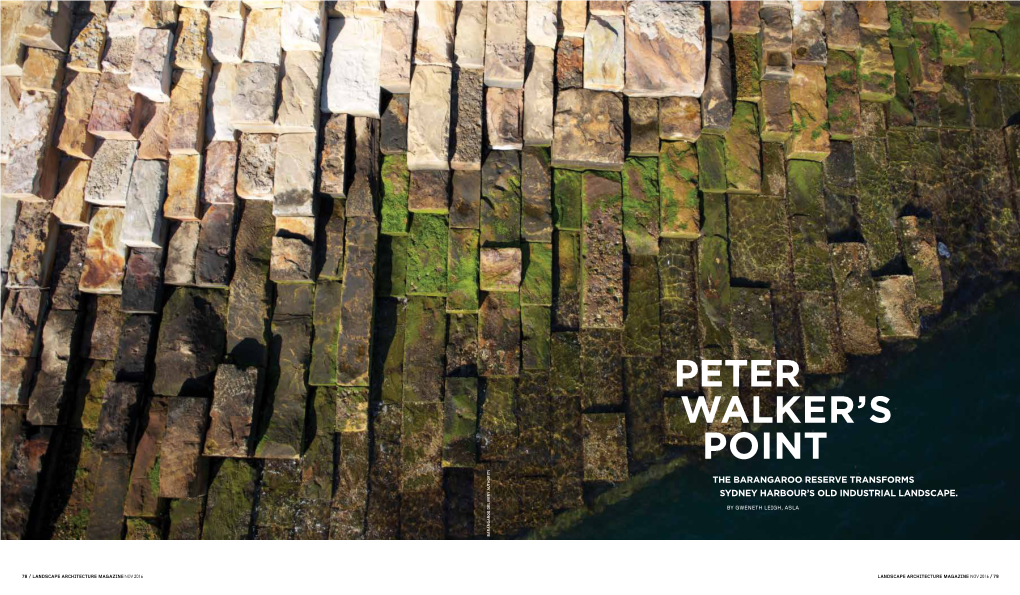

Peter Walker's Point

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sydney Harbour a Systematic Review of the Science 2014

Sydney Harbour A systematic review of the science 2014 Sydney Institute of Marine Science Technical Report The Sydney Harbour Research Program © Sydney Institute of Marine Science, 2014 This publication is copyright. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material provided that the wording is reproduced exactly, the source is acknowledged, and the copyright, update address and disclaimer notice are retained. Disclaimer The authors of this report are members of the Sydney Harbour Research Program at the Sydney Institute of Marine Science and represent various universities, research institutions and government agencies. The views presented in this report do not necessarily reflect the views of The Sydney Institute of Marine Science or the authors other affiliated institutions listed below. This report is a review of other literature written by third parties. Neither the Sydney Institute of Marine Science or the affiliated institutions take responsibility for the accuracy, currency, reliability, and correctness of any information included in this report provided in third party sources. Recommended Citation Hedge L.H., Johnston E.L., Ayoung S.T., Birch G.F., Booth D.J., Creese R.G., Doblin M.A., Figueira W.F., Gribben P.E., Hutchings P.A., Mayer Pinto M, Marzinelli E.M., Pritchard T.R., Roughan M., Steinberg P.D., 2013, Sydney Harbour: A systematic review of the science, Sydney Institute of Marine Science, Sydney, Australia. National Library of Australia Cataloging-in-Publication entry ISBN: 978-0-646-91493-0 Publisher: The Sydney Institute of Marine Science, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia Available on the internet from www.sims.org.au For further information please contact: SIMS, Building 19, Chowder Bay Road, Mosman NSW 2088 Australia T: +61 2 9435 4600 F: +61 2 9969 8664 www.sims.org.au ABN 84117222063 Cover Photo | Mike Banert North Head The light was changing every minute. -

Ultimo Tafe Nsw

SANDSTONE CARVINGS RECORDING ULTIMO TAFE NSW 1 SANDSTONE CARVINGS RECORDING ULTIMO TAFE NSW CONTENTS PART 1 INTRODUCTION 9 OVERVIEW 11 PART 2 PHOTOGRAPHIC RECORDING 17 PART 3 CONCISE REPORT 227 PART 1 INTRODUCTION & OVERVIEW 6 7 INTRODUCTION BACKGROUND This document presents a photographic record of sandstone carvings which adorn Buildings A, B & C, Ultimo TAFE, Sydney. Close to 100 carvings adorn the facade. Incorporated within the imposts and finials, the carvings largely depict Australian flora and fauna motifs. Funding was provided by the NSW Public Works Minister’s Stonework Program. Included is an inventory which identifies the principle features on each unique carving and an investigation into the history, context and significance of the carvings. Photography was undertaken in 2012-13 from scaffold constructed for façade repairs. No repairs were carried out on the carvings at this time. Recording significant carvings is an important aspect of stone conservation. It provides a record of the current condition of the stone, documentary evidence which can help determine the rate of deterioration when compared with future condition. Photographs record information for future generations, should they choose to re-carve due to loss of all recognisable detail. Recording also provides public access to and appreciation of these skilfully executed and unique carving located high on the façade. ACKNOWLEDGEMENT This report was prepared by the Government Architect’s Office. Joy Singh and Katie Hicks co-ordinated and compiled the report, graphic design by Marietta Buikema and drawings by Milena Crawford. The history, context and significance were researched and written by Margaret Betteridge of MuseCape and Photography by Michael Nicholson. -

Some Unpublished Correspondence of the Rev. W.B. Clarke D.F

Journal & Proceedings of the Royal Society of New South Wales, Vol. 141, p. 1–31, 2008 ISSN 0035-9173/08/02001–31 $4.00/1 Some Unpublished Correspondence of the Rev. W.B. Clarke d.f. branagan and t.g. vallance Abstract: Four previously unpublished letters, with memoranda of Rev. W.B. Clarke to W.S. Macleay, written between 1842 and 1845 clarify the ideas of both about the mode of formation of coal and the age of the stratigraphical succession in the Sydney Basin. Clarke makes the first mention of his discovery of the Lake Macquarie fossil forest, the first identification of the zeolite stilbite in New South Wales and gives details of his study of the volcanic rocks of the Upper Hunter Valley. Keywords: Clarke, Macleay, coal formation, Sydney Basin, stilbite INTRODUCTION essentially self-contained, although, of course, almost no letter can stand alone, but depends When Dr Thomas G. Vallance died in 1993 a on the correspondents. Each letter has some considerable amount of his historical jottings importance in dealing with aspects of Clarke’s and memorabilia on the history of Australian geological work, as will be noted. science, and particularly geology, was passed The first and longest letter, which is ac- on to me (David Branagan) through his wife, companied by a long series of memoranda and Hilary Vallance. For various reasons, only now a labelled sketch fits between two letters from have I been able to delve, even tentatively, into MacLeay (28 June & 4 July 1842) to Clarke. this treasure house. The present note con- Both these MacLeay letters have been repro- cerns four letters of the Reverend W.B. -

Fossil Footprints Found in Sydney Suburb Are from the Earliest Swimming Tetrapods in Australia 13 May 2020, by Phil Bell

Fossil footprints found in Sydney suburb are from the earliest swimming tetrapods in Australia 13 May 2020, by Phil Bell Australian Museum in Sydney, where they were displayed for a short period in the 1950s, but were later moved into the research collections. The trackway measures 4.2 meters long and consists of at least 35 foot and handprints. Only two fingers from each hand and foot made their impressions in the sandy bottom, making the precise identity of the animal difficult to establish. Researchers at the University of New England determined that it was likely a temnospondyl (an extinct group of salamander-like amphibians) Credit: Journal of Paleontology (2020). DOI: between 0.8 and 1.35 m long, the bones of which 10.1017/jpa.2020.22 are reasonably well-known from rocks in the Sydney region. Despite this, animal fossils are extremely rare in Sydney sandstone. Fossil footprints discovered nearly 80 years ago in The tracks are also significant because they are the a sandstone quarry at Berowra have been oldest record of a swimming tetrapod—that is, all identified as the traces of a four-legged animal animals with four legs, including humans—from swimming in a river nearly a quarter of a billion Australia. "The foot and hand prints, along with the years ago. gaps between the sequence of traces, were unlike anything I had seen before. This led me to believe The footprints were identified by Roy Minden the animal was swimming in water," said Farman, Farman, a former masters student at the University who led the study. -

Artist Biographies

Parko Techni 2018 Artist Biographies Khaled Sabsabi Born in 1965, Tripoli, Lebanon and currently lives and works in Sydney, Australia. Education, Master of Arts, Time Based Art major at COFA, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. Khaled Sabsabi’s process involves working across art mediums, geographical borders and cultures to create immersive and engaging art experiences. He see’s art as an effective tool to communicate with people, through a familiar language. Sabsabi makes work that questions; rationales and complexities of nationhood, identity and change. His practice speaks to audiences in ways that enlighten our understanding of universal dynamics which is more complex and ultimately more unknowable than our own selves. Khaled was awarded the Helen Lempriere Travelling Art Scholarship in 2010, 60th Blake Prize in 2011, MCG Basil Sellers fellowship in 2014, the Fishers Ghost Prize in 2014 and the Western Sydney ARTS NSW Fellowship 2015. He is represented by Milani Gallery, Brisbane and has 14 works in private, national and international collections. He has also participated in the 3rd Kochi Biennale, 1st Yinchuan Biennale, 5th Marrakech Biennale, 18th Biennale of Sydney, 9th Shanghai Biennale and Sharjah Biennial 11. Lumiforms Lumiforms make interactive light and sound installations. Working in the public sphere, we aim to create tactile and engaging experiences for all audiences. Our services include interactive lighting and sound design, custom fabrication and installation, 3D design and prototyping, interactive visualisation, concept development and consultation. We work closely with architects, engineers, industrial designers and creative programmers to produce works for VIVID Sydney, Sydney Opera House, Parliament House, The Power House Museum, UNSW The Galleries and Glow Festival, as well as other events and exhibitions both locally and internationally. -

STONE MASONRY in SOUTH AUSTRALIA I DEPARTMENT of ENVIRONMENT and NATURAL RESOUCES Published By

RITAG HE E CP ONSERVATION RACTICE NOTES TECHNICAL NOTE 3.6 STONE MASONRY IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA i DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOUCES Published by DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES October 1993 ©October Department 1993 of Environment and Natural Resources and David Young © Department of Environment and NovemberNatural Resources; 2007 and David Young Published online without revision DepartmentSeptember 2008 for Environment and Heritage Published online without revision ISSNDepartment 1035-5138 for Environment and Heritage Prepared by State Heritage Branch DesignISSN 1035-5138 by Technical Services Branch TPreparedext and byphotographs State Heritage by BranchDavid Young Design by Technical Services Branch TextDEH andInformation photographs Line by(08) David 8204 Young 1910 Website: www.environment.sa.gov.au DEHEmail: Information [email protected] Line (08) 8204 1910 u Website www.environment.sa.gov.au Email [email protected] Disclaimer WhileCover reasonablephoto: Carved efforts panel have in been Sydney made sandstone. to ensure the contents of this publication are factually correct, Former Marine and Harbours Building, 1884, the Department for Environment and Heritage makes no representations and accepts no responsibility for Victoria Square. the accuracy or completeness of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this publication. Printed on recycled paper Cover photo: Carved -

The Building Stones of St. John'8 Cathedral. Brisbane

THE BUILDING STONES OF ST. JOHN'8 CATHEDRAL. BRISBANE. By HENRY C. RICHARDS, M.Sc., Lectur. er in Geology, University of Queer;sland. ]lead before the Royal Society of Queensland, August 26th, 1911. INTRODUCTION. HA YING witnessed the growth of this building which is likely to be a prominent feature for a long time in Brisbane, and being somewhat acquainted with the stones used in its construction, the recording of available information would seem to the author to serve a useful purpose. In the choice of the building stone, its actual mode of weathering in a structure is of first importance, but failing this, the practice of carrying out mechanical and laboratory tests approximating as far as possible the actual conditions is resorted to. While these latter tests are extremely useful, that, under normal conditions, is the real one. Unfortunately, records of the stones used in old buildings are generally unobtainable, thus, much of the information to be obtained from a study of the weather ing of the stones in old structures is thereby lost ; hence the importance of accurately recording the available information and current opinions as to the stones at the earliest opportunity. STONES . USED IN THE BUILDING. These have been gathered from three Australian States, although the bulk of the material is of local origin, and both igneous and sedimentary rocks have been used. Five different stones, of which the following is a list, are contained m the structure :- Tuff Locality Brisbane. Sandstone Helidon, Queensland Sandstone Sydney. Granite Harcourt, Victoria. Basalt Footscray, Victoria. ' 200 BUILDING STONES OF ST. -

New South Wales from 1810 to 1821

Attraction information Sydney..................................................................................................................................................................................2 Sydney - St. Mary’s Cathedral ..............................................................................................................................................3 Sydney - Mrs Macquarie’s Chair ..........................................................................................................................................4 Sydney - Hyde Park ..............................................................................................................................................................5 Sydney - Darling Harbour .....................................................................................................................................................7 Sydney - Opera House .........................................................................................................................................................8 Sydney - Botanic Gardens ................................................................................................................................................. 10 Sydney - Sydney Harbour Bridge ...................................................................................................................................... 11 Sydney - The Rocks .......................................................................................................................................................... -

Urban Design in Central Sydney 1945–2002: Laissez-Faire and Discretionary Traditions in the Accidental City John Punter

Progress in Planning 63 (2005) 11–160 www.elsevier.com/locate/pplann Urban design in central Sydney 1945–2002: Laissez-Faire and discretionary traditions in the accidental city John Punter School of City and Regional Planning, Cardiff University, Cardiff CF10 3WA, UK Abstract This paper explores the laissez faire and discretionary traditions adopted for development control in Central Sydney over the last half century. It focuses upon the design dimension of control, and the transition from a largely design agnostic system up until 1988, to the serious pursuit of design excellence by 2000. Six eras of design/development control are identified, consistent with particular market conditions of boom and bust, and with particular political regimes at State and City levels. The constant tensions between State Government and City Council, and the interventions of state advisory committees and development agencies, Tribunals and Courts are explored as the pursuit of design quality moved from being a perceived barrier to economic growth to a pre-requisite for global competitiveness in the pursuit of international investment and tourism. These tensions have given rise to the description of Central Sydney as ‘the Accidental City’. By contrast, the objective of current policy is to consistently achieve ‘the well-mannered and iconic’ in architecture and urban design. Beginning with the regulation of building height by the State in 1912, the Council’s development approval powers have been severely curtailed by State committees and development agencies, by two suspensions of the Council, and more recently (1989) by the establishment of a joint State- Council committee to assess major development applications. -

Bringelly Shale

AUSTRALIAN MUSEUM SCIENTIFIC PUBLICATIONS Lovering, J. F., 1954. The stratigraphy of the Wianamatta Group Triassic System, Sydney Basin. Records of the Australian Museum 23(4): 169–210, plate xii. [25 June 1954]. doi:10.3853/j.0067-1975.23.1954.631 ISSN 0067-1975 Published by the Australian Museum, Sydney naturenature cultureculture discover discover AustralianAustralian Museum Museum science science is is freely freely accessible accessible online online at at www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/www.australianmuseum.net.au/publications/ 66 CollegeCollege Street,Street, SydneySydney NSWNSW 2010,2010, AustraliaAustralia THE STRATIGRAPHY OF THE WIANAMATTA GROUP TRIASSIC SYSTEM, SYDNEY BASIN BY J. F. LOVERING, M.Sc. Assistant Curator of Minerals and Rocks, The Australian Museum, Sydney. (Plate xii, ten text-figures; eight maps.) Introduction. Methods of Mapping. Stratigraphy. A. General Definition. B. Liverpool Sub-group: (i) Ashfield Shale: (ii) Minchinbury Sandstone: (iii) Bringelly Shale. C. Camden Sub-group : (i) Potts Hill Sandstone; (ii) Annan Shale; (iii) Razorback Sandstone; (iv) Picton Formation; (v) PrndhQe Shale. Sedimentary Petrology and Petrography of the Sandstone 'Formations. The Sedimentary Environment and Sedimentary Tectonics. Post-Depositional Tectonics. SYNOPSIS. The Wianamatta Group has been divided into two Sub-groups-The Liverpool Sub-group (lower. approximately 400 feet thick, predominantly shale lithology) and the Camden Sub-group (upper, approximately 350 feet thick, sandstone lit.hology prominent with shale). The Uverpool Sub-group includes three formations (Ashfield Shale, Minchinbury Sandstone, Bringelly Shale). The Camden Sub-group includes five formations (Potts Hill Sandstone, Annan Shale, Razorback Sandstone, Picton Formation, Prudhoe Shale). The sedimentary petrology of the graywacke-type .sandstones and the relation of the lithology to the sedimentary environment and tectonics is discussed. -

Façade Cleaning of Sydney's Former General Post Office Kick-Starts Brand Conversion to the Fullerton Hotel Sydney

Media release Façade cleaning of Sydney’s former General Post Office kick-starts brand conversion to The Fullerton Hotel Sydney Remediation project part of broader programme to connect locals with historic landmark SYDNEY, Australia—16 April 2019: In the lead up to the launch of The Fullerton Hotel Sydney in the former Sydney General Post Office (GPO)—the vision for which is to become the city’s luxury heritage hotel in the heart of the CBD—remediation and maintenance work on the façade of the historic landmark has commenced. Built on a grand scale and at huge expense, Australia’s first GPO building dominated the Sydney streetscape and skyline for decades. Constructed in two stages, beginning in 1866 and designed under the guidance of colonial architect James Barnet, the GPO was regarded as a building which would come to symbolise Sydney in the same way the Houses of Parliament in Westminster represent London and the Eiffel Tower, Paris. With its intricate stone work and carvings causing a public outcry when it was first launched, the GPO remained Sydney’s most well-known landmark since 1874 until the Sydney Harbour Bridge was erected in 1932. With extensive experience preserving historic buildings in The Fullerton Heritage precinct in Singapore, the Hotel’s future operator The Fullerton Hotels and Resorts is committed to the conservation of the Sydney GPO building for future generations. Cleaning its iconic façade is the first step of a broader remediation programme. “As custodians of heritage, we believe it’s imperative that significant historical buildings such as the GPO retain their heritage features. -

Façade Cleaning of Sydney's Former General Post Office Kick-Starts Brand Conversion to the Fullerton Hotel Sydney

Media release Façade cleaning of Sydney’s former General Post Office kick-starts brand conversion to The Fullerton Hotel Sydney Remediation project part of broader programme to connect locals with historic landmark SYDNEY, Australia—16 April 2019: In the lead up to the launch of The Fullerton Hotel Sydney in the former Sydney General Post Office (GPO)—the vision for which is to become the city’s luxury heritage hotel in the heart of the CBD—remediation and maintenance work on the façade of the historic landmark has commenced. Built on a grand scale and at huge expense, Australia’s first GPO building dominated the Sydney streetscape and skyline for decades. Constructed in two stages, beginning in 1866 and designed under the guidance of colonial architect James Barnet, the GPO was regarded as a building which would come to symbolise Sydney in the same way the Houses of Parliament in Westminster represent London and the Eiffel Tower, Paris. With its intricate stone work and carvings causing a public outcry when it was first launched, the GPO remained Sydney’s most well-known landmark since 1874 until the Sydney Harbour Bridge was erected in 1932. With extensive experience preserving historic buildings in The Fullerton Heritage precinct in Singapore, the Hotel’s future operator The Fullerton Hotels and Resorts is committed to the conservation of the Sydney GPO building for future generations. Cleaning its iconic façade is the first step of a broader remediation programme. “As custodians of heritage, we believe it’s imperative that significant historical buildings such as the GPO retain their heritage features.