Basic Plasma Physics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

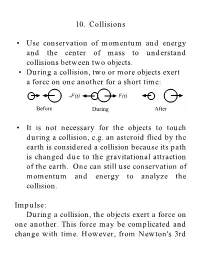

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

VISCOSITY of a GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, a N College, Patna

Lecture Note on VISCOSITY OF A GAS -Dr S P Singh Department of Chemistry, A N College, Patna A sketchy summary of the main points Viscosity of gases, relation between mean free path and coefficient of viscosity, temperature and pressure dependence of viscosity, calculation of collision diameter from the coefficient of viscosity Viscosity is the property of a fluid which implies resistance to flow. Viscosity arises from jump of molecules from one layer to another in case of a gas. There is a transfer of momentum of molecules from faster layer to slower layer or vice-versa. Let us consider a gas having laminar flow over a horizontal surface OX with a velocity smaller than the thermal velocity of the molecule. The velocity of the gaseous layer in contact with the surface is zero which goes on increasing upon increasing the distance from OX towards OY (the direction perpendicular to OX) at a uniform rate . Suppose a layer ‘B’ of the gas is at a certain distance from the fixed surface OX having velocity ‘v’. Two layers ‘A’ and ‘C’ above and below are taken into consideration at a distance ‘l’ (mean free path of the gaseous molecules) so that the molecules moving vertically up and down can’t collide while moving between the two layers. Thus, the velocity of a gas in the layer ‘A’ ---------- (i) = + Likely, the velocity of the gas in the layer ‘C’ ---------- (ii) The gaseous molecules are moving in all directions due= to −thermal velocity; therefore, it may be supposed that of the gaseous molecules are moving along the three Cartesian coordinates each. -

Viscosity of Gases References

VISCOSITY OF GASES Marcia L. Huber and Allan H. Harvey The following table gives the viscosity of some common gases generally less than 2% . Uncertainties for the viscosities of gases in as a function of temperature . Unless otherwise noted, the viscosity this table are generally less than 3%; uncertainty information on values refer to a pressure of 100 kPa (1 bar) . The notation P = 0 specific fluids can be found in the references . Viscosity is given in indicates that the low-pressure limiting value is given . The dif- units of μPa s; note that 1 μPa s = 10–5 poise . Substances are listed ference between the viscosity at 100 kPa and the limiting value is in the modified Hill order (see Introduction) . Viscosity in μPa s 100 K 200 K 300 K 400 K 500 K 600 K Ref. Air 7 .1 13 .3 18 .5 23 .1 27 .1 30 .8 1 Ar Argon (P = 0) 8 .1 15 .9 22 .7 28 .6 33 .9 38 .8 2, 3*, 4* BF3 Boron trifluoride 12 .3 17 .1 21 .7 26 .1 30 .2 5 ClH Hydrogen chloride 14 .6 19 .7 24 .3 5 F6S Sulfur hexafluoride (P = 0) 15 .3 19 .7 23 .8 27 .6 6 H2 Normal hydrogen (P = 0) 4 .1 6 .8 8 .9 10 .9 12 .8 14 .5 3*, 7 D2 Deuterium (P = 0) 5 .9 9 .6 12 .6 15 .4 17 .9 20 .3 8 H2O Water (P = 0) 9 .8 13 .4 17 .3 21 .4 9 D2O Deuterium oxide (P = 0) 10 .2 13 .7 17 .8 22 .0 10 H2S Hydrogen sulfide 12 .5 16 .9 21 .2 25 .4 11 H3N Ammonia 10 .2 14 .0 17 .9 21 .7 12 He Helium (P = 0) 9 .6 15 .1 19 .9 24 .3 28 .3 32 .2 13 Kr Krypton (P = 0) 17 .4 25 .5 32 .9 39 .6 45 .8 14 NO Nitric oxide 13 .8 19 .2 23 .8 28 .0 31 .9 5 N2 Nitrogen 7 .0 12 .9 17 .9 22 .2 26 .1 29 .6 1, 15* N2O Nitrous -

Law of Conversation of Energy

Law of Conservation of Mass: "In any kind of physical or chemical process, mass is neither created nor destroyed - the mass before the process equals the mass after the process." - the total mass of the system does not change, the total mass of the products of a chemical reaction is always the same as the total mass of the original materials. "Physics for scientists and engineers," 4th edition, Vol.1, Raymond A. Serway, Saunders College Publishing, 1996. Ex. 1) When wood burns, mass seems to disappear because some of the products of reaction are gases; if the mass of the original wood is added to the mass of the oxygen that combined with it and if the mass of the resulting ash is added to the mass o the gaseous products, the two sums will turn out exactly equal. 2) Iron increases in weight on rusting because it combines with gases from the air, and the increase in weight is exactly equal to the weight of gas consumed. Out of thousands of reactions that have been tested with accurate chemical balances, no deviation from the law has ever been found. Law of Conversation of Energy: The total energy of a closed system is constant. Matter is neither created nor destroyed – total mass of reactants equals total mass of products You can calculate the change of temp by simply understanding that energy and the mass is conserved - it means that we added the two heat quantities together we can calculate the change of temperature by using the law or measure change of temp and show the conservation of energy E1 + E2 = E3 -> E(universe) = E(System) + E(Surroundings) M1 + M2 = M3 Is T1 + T2 = unknown (No, no law of conservation of temperature, so we have to use the concept of conservation of energy) Total amount of thermal energy in beaker of water in absolute terms as opposed to differential terms (reference point is 0 degrees Kelvin) Knowns: M1, M2, T1, T2 (Kelvin) When add the two together, want to know what T3 and M3 are going to be. -

Optimization of Ion Flow Rates in a Helicon Injected IEC Fusion System

Aeronautics and Aerospace Open Access Journal Research Article Open Access Optimization of ion flow rates in a helicon injected IEC fusion system Abstract Volume 4 Issue 2 - 2020 The Helicon Injected Inertial Electrostatic Confinement (IEC) offers an attractive D-D Qiheng Cai, George H Miley neutron source for neutron commercial and homeland security activation neutron analysis. Department of Nuclear, Plasma & Radiological Engineering, Designs with multiple injectors also provide a potential route to an attractive small fusion University of Illinois at Champaign-Urbana, USA reactor. Use of such a reactor has also been studied for deep space propulsion. In addition, a non-fusion design been studied for use as an electric thruster for near-term space Correspondence: Qiheng Cai, Department of Nuclear, Plasma applications. The Helicon Inertial Plasma Electrostatic Rocket (HIIPER) is an advanced & Radiological Engineering, University of Illinois at Champaign- space plasma thruster coupling the helicon and a modified IEC. A key aspect for all of these Urbana, Urbana, IL, 61801, Tel +15712679353, systems is to develop efficient coupling between the Helicon plasma injector and the IEC. Email This issue is under study and will be described in this presentation. To analyze the coupling efficiency, ion flow rates (which indicate how many ions exit the helicon and enter the IEC Received: May 01, 2020 | Published: May 21, 2020 device per second) are investigated by a global model. In this simulation particle rate and power balance equations are solved to investigate the time evolution of electron density, neutral density and electron temperature in the helicon tube. In addition to the Helicon geometry and RF field design, the use of a potential bias plate at the gas inlet of the Helicon is considered. -

Plasma Physics I APPH E6101x Columbia University Fall, 2016

Lecture 1: Plasma Physics I APPH E6101x Columbia University Fall, 2016 1 Syllabus and Class Website http://sites.apam.columbia.edu/courses/apph6101x/ 2 Textbook “Plasma Physics offers a broad and modern introduction to the many aspects of plasma science … . A curious student or interested researcher could track down laboratory notes, older monographs, and obscure papers … . with an extensive list of more than 300 references and, in particular, its excellent overview of the various techniques to generate plasma in a laboratory, Plasma Physics is an excellent entree for students into this rapidly growing field. It’s also a useful reference for professional low-temperature plasma researchers.” (Michael Brown, Physics Today, June, 2011) 3 Grading • Weekly homework • Two in-class quizzes (25%) • Final exam (50%) 4 https://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sdo/overview/ Launched 11 Feb 2010 5 http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/sdo/news/sdo-year2.html#.VerqQLRgyxI 6 http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/MAST.aspx http://www.ccfe.ac.uk/mast_upgrade_project.aspx 7 https://youtu.be/svrMsZQuZrs 8 9 10 ITER: The International Burning Plasma Experiment Important fusion science experiment, but without low-activation fusion materials, tritium breeding, … ~ 500 MW 10 minute pulses 23,000 tonne 51 GJ >30B $US (?) DIII-D ⇒ ITER ÷ 3.7 (50 times smaller volume) (400 times smaller energy) 11 Prof. Robert Gross Columbia University Fusion Energy (1984) “Fusion has proved to be a very difficult challenge. The early question was—Can fusion be done, and, if so how? … Now, the challenge lies in whether fusion can be done in a reliable, an economical, and socially acceptable way…” 12 http://lasco-www.nrl.navy.mil 13 14 Plasmasphere (Image EUV) 15 https://youtu.be/TaPgSWdcYtY 16 17 LETTER doi:10.1038/nature14476 Small particles dominate Saturn’s Phoebe ring to surprisingly large distances Douglas P. -

Plasma Physics and Advanced Fluid Dynamics Jean-Marcel Rax (Univ. Paris-Saclay, Ecole Polytechnique), Christophe Gissinger (LPEN

Plasma Physics and advanced fluid dynamics Jean-Marcel Rax (Univ. Paris-Saclay, Ecole Polytechnique), Christophe Gissinger (LPENS)) I- Plasma Physics : principles, structures and dynamics, waves and instabilities Besides ordinary temperature usual (i) solid state, (ii) liquid state and (iii) gaseous state, at very low and very high temperatures new exotic states appear : (iv) quantum fluids and (v) ionized gases. These states display a variety of specific and new physical phenomena : (i) at low temperature quantum coherence, correlation and indiscernibility lead to superfluidity, su- perconductivity and Bose-Einstein condensation ; (ii) at high temperature ionization provides a significant fraction of free charges responsible for in- stabilities, nonlinear, chaotic and turbulent behaviors characteristic of the \plasma state". This set of lectures provides an introduction to the basic tools, main results and advanced methods of Plasma Physics. • Plasma Physics : History, orders of magnitudes, Bogoliubov's hi- erarchy, fluid and kinetic reductions. Electric screening : Langmuir frequency, Maxwell time, Debye length, hybrid frequencies. Magnetic screening : London and Kelvin lengths. Alfven and Bohm velocities. • Charged particles dynamics : adiabaticity and stochasticity. Alfven and Ehrenfest adiabatic invariants. Electric and magnetic drifts. Pon- deromotive force. Wave/particle interactions : Chirikov criterion and chaotic dynamics. Quasilinear kinetic equation for Landau resonance. • Structure and self-organization : Debye and Child-Langmuir sheath, Chapman-Ferraro boundary layer. Brillouin and basic MHD flow. Flux conservation : Alfven's theorem. Magnetic topology : magnetic helicity conservation. Grad-Shafranov and basic MHD equilibrium. • Waves and instabilities : Fluid and kinetic dispersions : resonance and cut-off. Landau and cyclotron absorption. Bernstein's modes. Fluid instabilities : drift, interchange and kink. Alfvenic and geometric coupling. -

Plasma Descriptions I: Kinetic, Two-Fluid 1

CHAPTER 5. PLASMA DESCRIPTIONS I: KINETIC, TWO-FLUID 1 Chapter 5 Plasma Descriptions I: Kinetic, Two-Fluid Descriptions of plasmas are obtained from extensions of the kinetic theory of gases and the hydrodynamics of neutral uids (see Sections A.4 and A.6). They are much more complex than descriptions of charge-neutral uids because of the complicating eects of electric and magnetic elds on the motion of charged particles in the plasma, and because the electric and magnetic elds in the plasma must be calculated self-consistently with the plasma responses to them. Additionally, magnetized plasmas respond very anisotropically to perturbations — because charged particles in them ow almost freely along magnetic eld lines, gyrate about the magnetic eld, and drift slowly perpendicular to the magnetic eld. The electric and magnetic elds in a plasma are governed by the Maxwell equations (see Section A.2). Most calculations in plasma physics assume that the constituent charged particles are moving in a vacuum; thus, the micro- scopic, “free space” Maxwell equations given in (??) are appropriate. For some applications the electric and magnetic susceptibilities (and hence dielectric and magnetization responses) of plasmas are derived (see for example Sections 1.3, 1.4 and 1.6); then, the macroscopic Maxwell equations are used. Plasma eects enter the Maxwell equations through the charge density and current “sources” produced by the response of a plasma to electric and magnetic elds: X X q = nsqs, J = nsqsVs, plasma charge, current densities. (5.1) s s Here, the subscript s indicates the charged particle species (s = e, i for electrons, 3 ions), ns is the density (#/m ) of species s, qs the charge (Coulombs) on the species s particles, and Vs the species ow velocity (m/s). -

Specific Latent Heat

SPECIFIC LATENT HEAT The specific latent heat of a substance tells us how much energy is required to change 1 kg from a solid to a liquid (specific latent heat of fusion) or from a liquid to a gas (specific latent heat of vaporisation). �����푦 (��) 퐸 ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� ������� �� = (��⁄��) = 푓 � ����� (��) �����푦 = ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� 퐸 = ��푓 × � ������� × ����� ����� 퐸 � = �� 푦 푓 ����� = ����������푐 ������� ℎ���� �� ������� WORKED EXAMPLE QUESTION 398 J of energy is needed to turn 500 g of liquid nitrogen into at gas at-196°C. Calculate the specific latent heat of vaporisation of nitrogen. ANSWER Step 1: Write down what you know, and E = 99500 J what you want to know. m = 500 g = 0.5 kg L = ? v Step 2: Use the triangle to decide how to 퐸 ��푣 = find the answer - the specific latent heat � of vaporisation. 99500 퐽 퐿 = 0.5 �� = 199 000 ��⁄�� Step 3: Use the figures given to work out 푣 the answer. The specific latent heat of vaporisation of nitrogen in 199 000 J/kg (199 kJ/kg) Questions 1. Calculate the specific latent heat of fusion if: a. 28 000 J is supplied to turn 2 kg of solid oxygen into a liquid at -219°C 14 000 J/kg or 14 kJ/kg b. 183 600 J is supplied to turn 3.4 kg of solid sulphur into a liquid at 115°C 54 000 J/kg or 54 kJ/kg c. 6600 J is supplied to turn 600g of solid mercury into a liquid at -39°C 11 000 J/kg or 11 kJ/kg d. -

Plasma Waves

Plasma Waves S.M.Lea January 2007 1 General considerations To consider the different possible normal modes of a plasma, we will usually begin by assuming that there is an equilibrium in which the plasma parameters such as density and magnetic field are uniform and constant in time. We will then look at small perturbations away from this equilibrium, and investigate the time and space dependence of those perturbations. The usual notation is to label the equilibrium quantities with a subscript 0, e.g. n0, and the pertrubed quantities with a subscript 1, eg n1. Then the assumption of small perturbations is n /n 1. When the perturbations are small, we can generally ignore j 1 0j ¿ squares and higher powers of these quantities, thus obtaining a set of linear equations for the unknowns. These linear equations may be Fourier transformed in both space and time, thus reducing the differential equations to a set of algebraic equations. Equivalently, we may assume that each perturbed quantity has the mathematical form n = n exp i~k ~x iωt (1) 1 ¢ ¡ where the real part is implicitly assumed. Th³is form descri´bes a wave. The amplitude n is in ~ general complex, allowing for a non•zero phase constant φ0. The vector k, called the wave vector, gives both the direction of propagation of the wave and the wavelength: k = 2π/λ; ω is the angular frequency. There is a relation between ω and ~k that is determined by the physical properties of the system. The function ω ~k is called the dispersion relation for the wave. -

Density Functional Theory

Density Functional Theory Fundamentals Video V.i Density Functional Theory: New Developments Donald G. Truhlar Department of Chemistry, University of Minnesota Support: AFOSR, NSF, EMSL Why is electronic structure theory important? Most of the information we want to know about chemistry is in the electron density and electronic energy. dipole moment, Born-Oppenheimer charge distribution, approximation 1927 ... potential energy surface molecular geometry barrier heights bond energies spectra How do we calculate the electronic structure? Example: electronic structure of benzene (42 electrons) Erwin Schrödinger 1925 — wave function theory All the information is contained in the wave function, an antisymmetric function of 126 coordinates and 42 electronic spin components. Theoretical Musings! ● Ψ is complicated. ● Difficult to interpret. ● Can we simplify things? 1/2 ● Ψ has strange units: (prob. density) , ● Can we not use a physical observable? ● What particular physical observable is useful? ● Physical observable that allows us to construct the Hamiltonian a priori. How do we calculate the electronic structure? Example: electronic structure of benzene (42 electrons) Erwin Schrödinger 1925 — wave function theory All the information is contained in the wave function, an antisymmetric function of 126 coordinates and 42 electronic spin components. Pierre Hohenberg and Walter Kohn 1964 — density functional theory All the information is contained in the density, a simple function of 3 coordinates. Electronic structure (continued) Erwin Schrödinger