Government Spending on Poverty Alleviation Through Co-Operatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizens Wealth Platform 2017

2017 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Of the States in the SOUTH-EAST Geo-Political Zone C P W Citizens Wealth Platform Citizen Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2017 FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET of the States in the SOUTH EAST Geo-Political Zone Compiled by VICTOR EMEJUIWE For Citizens Wealth Platform (CWP) (Public Resources Are Made To Work And Be Of Benefit To All) 2017 SOUTH EAST FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Page 2 First Published in August 2017 By Citizens Wealth Platform C/o Centre for Social Justice 17 Yaounde Street, Wuse Zone 6, Abuja Email: [email protected] Website: www.csj-ng.org Tel: 08055070909. Blog: csj-blog.org. Twitter:@censoj. Facebook: Centre for Social Justice, Nigeria 2017 SOUTH EAST FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Page 3 Table of Contents Foreword 5 Abia State 6 Anambra State 26 Embonyi State 46 Enugu State 60 Imo State 82 2017 SOUTH EAST FEDERAL CAPITAL BUDGET PULLOUT Page 4 Foreword In the spirit of the mandate of the Citizens Wealth Platform to ensure that public resources are made to work and be of benefit to all, we present the South East Capital Budget Pullout for the financial year 2017. This has been our tradition in the last six years to provide capital budget information to all Nigerians. The pullout provides information on federal Ministries, Departments and Agencies, names of projects, amount allocated and their location. The Economic Recovery and Growth Plan (ERGP) is the Federal Government’s blueprint for the resuscitation of the economy and its revival from recession. -

University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository University of Calgary Press University of Calgary Press Open Access Books 2010 The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria Korieh, Chima J. University of Calgary Press Chima J. Korieh. "The land has changed: history, society and gender in colonial Eastern Nigeria". Series: Africa, missing voices series 6, University of Calgary Press, Calgary, Alberta, 2010. http://hdl.handle.net/1880/48254 book http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives 3.0 Unported Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca University of Calgary Press www.uofcpress.com THE LAND HAS CHANGED History, Society and Gender in Colonial Eastern Nigeria Chima J. Korieh ISBN 978-1-55238-545-6 THIS BOOK IS AN OPEN ACCESS E-BOOK. It is an electronic version of a book that can be purchased in physical form through any bookseller or on-line retailer, or from our distributors. Please support this open access publication by requesting that your university purchase a print copy of this book, or by purchasing a copy yourself. If you have any questions, please contact us at [email protected] Cover Art: The artwork on the cover of this book is not open access and falls under traditional copyright provisions; it cannot be reproduced in any way without written permission of the artists and their agents. The cover can be displayed as a complete cover image for the purposes of publicizing this work, but the artwork cannot be extracted from the context of the cover of this specific work without breaching the artist’s copyright. -

Nigeria's Constitution of 1999

PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 constituteproject.org Nigeria's Constitution of 1999 This complete constitution has been generated from excerpts of texts from the repository of the Comparative Constitutions Project, and distributed on constituteproject.org. constituteproject.org PDF generated: 26 Aug 2021, 16:42 Table of contents Preamble . 5 Chapter I: General Provisions . 5 Part I: Federal Republic of Nigeria . 5 Part II: Powers of the Federal Republic of Nigeria . 6 Chapter II: Fundamental Objectives and Directive Principles of State Policy . 13 Chapter III: Citizenship . 17 Chapter IV: Fundamental Rights . 20 Chapter V: The Legislature . 28 Part I: National Assembly . 28 A. Composition and Staff of National Assembly . 28 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of National Assembly . 29 C. Qualifications for Membership of National Assembly and Right of Attendance . 32 D. Elections to National Assembly . 35 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 36 Part II: House of Assembly of a State . 40 A. Composition and Staff of House of Assembly . 40 B. Procedure for Summoning and Dissolution of House of Assembly . 41 C. Qualification for Membership of House of Assembly and Right of Attendance . 43 D. Elections to a House of Assembly . 45 E. Powers and Control over Public Funds . 47 Chapter VI: The Executive . 50 Part I: Federal Executive . 50 A. The President of the Federation . 50 B. Establishment of Certain Federal Executive Bodies . 58 C. Public Revenue . 61 D. The Public Service of the Federation . 63 Part II: State Executive . 65 A. Governor of a State . 65 B. Establishment of Certain State Executive Bodies . -

Paper Number

British Journal of Applied Science & Technology 4(34): 4751-4770, 2014 ISSN: 2231-0843 SCIENCEDOMAIN international www.sciencedomain.org Delineating Aquifer Systems Using Dar Zarouk Parameters Determined from Surface Geoelectric Survey: Case Study of Okigwe District, Southeastern Nigeria Leonard I. Nwosu1*, Cyril N. Nwankwo1 and Anthony S. Ekine1 1Department of Physics, University of Port Harcourt, Nigeria. Authors’ contributions This work was carried out in collaboration between all authors. Author LIN designed the study, wrote the protocol, carried out the field survey, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript and managed literature searches. Authors CNN, ASE managed the literature searches and analyses of the study data. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. Article Information DOI: 10.9734/BJAST/2014/7798 Editor(s): (1) Vyacheslav O. Vakhnenko, Division of Geodynamics of Explosion, Subbotin Institute of Geophysics, National Academy of Sciences of Ukrainian, Ukraine. Reviewers: (1) Amos-Uhegbu, Chukwunenyoke, Department of Physics (Geophysics), Michael Okpara University of Agriculture, Umudike Abia-State, Nigeria. (2) Emad A. M. Salah Al-Heety, Applied Geology, College of Science, University of Anbar, Iraq. (3) Anonymous, Enugu State University Enugu, Nigeria. (4) Anonymous, University of Calabar, Nigeria. Complete Peer review History: http://www.sciencedomain.org/review-history.php?iid=671&id=5&aid=6184 Received 11th November 2013 th Original Research Article Accepted 10 June 2014 rd Article………… Article Published 23 September 2014 ABSTRACT This study is aimed at delineating the aquifer systems in the study area and hence determining the parts with higher aquifer yield. To achieve this, 120 Vertical Electrical Soundings (VES) were carried out in Okigwe District of Imo State of Nigeria, using the Schlumberger electrode array and a maximum electrode spread of 900 m. -

River Basins of Imo State for Sustainable Water Resources

nvironm E en l & ta i l iv E C n g Okoro et al., J Civil Environ Eng 2014, 4:1 f o i n l Journal of Civil & Environmental e a e n r r i DOI: 10.4172/2165-784X.1000134 n u g o J ISSN: 2165-784X Engineering Review Article Open Access River Basins of Imo State for Sustainable Water Resources Management BC Okoro1*, RA Uzoukwu2 and NM Chimezie2 1Department of Civil Engineering, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria 2Department of Civil Engineering Technology, Federal Polytechnic Nekede, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria Abstract The river basins of Imo state, Nigeria are presented as a natural vital resource for sustainable water resources management in the area. The study identified most of all the known rivers in Imo State and provided information like relief, topography and other geographical features of the major rivers which are crucial to aid water management for a sustainable water infrastructure in the communities of the watershed. The rivers and lakes are classified into five watersheds (river basins) such as Okigwe watershed, Mbaise / Mbano watershed, Orlu watershed, Oguta watershed and finally, Owerri watershed. The knowledge of the river basins in Imo State will help analyze the problems involved in water resources allocation and to provide guidance for the planning and management of water resources in the state for sustainable development. Keywords: Rivers; Basins/Watersheds; Water allocation; • What minimum reservoir capacity will be sufficient to assure Sustainability adequate water for irrigation or municipal water supply, during droughts? Introduction • How much quantity of water will become available at a reservoir An understanding of the hydrology of a region or state is paramount site, and when will it become available? In other words, what in the development of such region (state). -

Coverage of Llin Among Expectant Mothers in Nwangele, Imo State, Nigeria

OPEN ACCESS International Journal of Applied Biology International Journal of Applied Biology is licensed under a ISSN : 2580-2410 Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any eISSN : 2580-2119 medium, provided the original work is properly cited. Coverage of Llin Among Expectant Mothers in Nwangele, Imo State, Nigeria Chiagoziem Ogazirilem Emerole1*, Dr. Salome Ibe1, Dr. Uchechukwu Madukaku Chukwuocha1, Prof. Eunice Nwoke1, Prof. Ikechukwu Dozie1, Prof. Okwuoma Abanobi1 1Department of Public Health, School of Health Technology, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. PMB 1526 Abstract Background: long-lasting insecticide-treated nets (LLINs) is one of the major interventions for the control and elimination of malaria, especially among Article History pregnant women. Received 12 April 2021 Aim: This study aimed to evaluate the knowledge, occurrence of malaria, Accepted 03 July 2021 utilisation and acquisition of long lasting insecticide treated net (LLINs) among pregnant women in Nwangele L.G.A. Imo State. Method: This was a cross-sectional study among women attending antenatal Keyword care in a primary health facility in Nwangele LGA, Imo State, Nigeria. A total of LLIN, Malaria, Nigeria, 150 women were interviewed using structured questionnaire to obtain Maternal health, Public information on their knowledge and the coverage of LLINs. Data analysis was Health done using SPSS version 20. Results: The mean age of the women was 29years. Most (81.3%) of the respondents had at least a secondary education. 92% used the LLINs at night time. Cost of acquiring these nets were free and in good condition (97.3%). -

IMO STATE Have Culminated in Crisis Before They Would Be Taken to the Regional Hospitals 6

COMMENTS FROM BENEFICIARIES OF OSSAP- - Ibeh Anthony C (Beneficiary, Small Town Water Scheme, Obokwu, Ezinihitte Mbaise LGA) MDGs CGS PROJECTS AND PROGRAMMES 4. We normally get water from a stream and a borehole from the town hall but now with the help of the MDGs we have clean drinkable water close to us and we have people from other communities come to get water too. 1. When we came into the communities as MDGs Technical Assistants, we - Livinus Iwuanyanwu (Beneficiary, Motorised Borehole, Umuezegwu, Ihitte Uboma LGA) established some institutional structures like the LGA committee and LGA technical team. The technical team went through the communities to know 5. Before MDGs built this motorized borehole, we used to go to a stream called their felt needs and thereafter raised a proposal to address those needs. During Nkwaf which is three and a half miles away and also a stream called Ezeahar one implementation, they are also involved in the monitoring and supervision of and half miles away. We also use the Oyibo stream which moves with the flood projects until they become a reality. The communities are happy with the MDGs and the water is not drinkable. It is not good for human consumption because because this is the first time any government agency is visiting them. of the things people throw into the water. Now, the MDGs have provided us with - Leonard C. Onyewu (MDGs Technical Assistant, Onuimo LGA) clean and potable water that is good for human consumption. We are grateful to the MDGs for this provision. 2. All the health centres have been fully utilized by the community people. -

Constituents Budget of Njaba River at Okwudor

IOSR Journal of Applied Geology and Geophysics (IOSR-JAGG) e-ISSN: 2321–0990, p-ISSN: 2321–0982.Volume 8, Issue 1 Ser. III (Jan – Feb 2020), PP 01-10 www.iosrjournals.org Constituents Budget of Njaba River at Okwudor Abiahu, C. M. G.,1 Ahiarakwem, C. A. 1Oli, I.C.,1Osi-Okeke, I.1and Meribe, P.N.1 Department of Geology, Federal University of Technology, Owerri, P.M.B 1526 Abstract The constituent budget of Njaba River at Okwudor was undertaken to understand the loading rate of constituents over a period of time (2011-2019). Water samples were obtained at equal distances of 2 km along the stretch of the River. The samples were obtained with the aid of sterilized 1.5 plastic bottle; the sample bottles were corked under water immediately after collection so as to prevent oxidation of the constituents. The water samples obtained from Okwudor was used to probe some physiochemical parameters and constituent budget of Njaba River over a period of eight years (2011 – 2019). The result indicates the pH of the River with values of 6.40 in 2011 and 6.44 in 2019. The TDS value for 2011 was 14.70 mg/l while for 2019 was 7.00 mg/l and the Total hardness of the water for 2011 was 11.80 mg/l and 2019 as 41.46 mg/l.The constituent budget 2+ 2+ + + 2- - - -3 indicates continuous loading of constituents (Ca ,Mg , Na , K ,SO 4,NO 3,Cl , and PO 4) into the Njabariver. - However, there was a decline in HCO 3.The constituent budgetindicates that Chlorine has the highest loading rate (2.97) while bicarbonate has the lowest loading rate (-0.63). -

Conflict Incident Monthly Tracker

Conflict Incident Monthly Tracker Imo State: July -August 2018 B a ck gro und congress, some youths burned down houses separate incident, some parishioners of a and injured some persons in Oguta LGA. church in Oguta LGA reportedly protested This monthly tracker is designed to update Separately, there was chaos in the State over the alleged removal of a priest in the Peace Agents on patterns and trends in House of Assembly following the alleged church. In a separate incident, there was a conflict risk and violence, as identified by the removal and replacement of the Majority protest by women over the destruction of Integrated Peace and Development Unit Leader of the House in Owerri Municipal their farms by herders in Amakohia-Ubi (IPDU) early warning system, and to seek LGA. In July, political tension was further community, Owerri Municipality. feedback and input for response to mitigate elevated in the state over the suspension of areas of conflict. some members of the Imo State House of Recent Incidents or Patterns and Trends Assembly and the impeachment of the Issues, August 2018 deputy governor of the state by 19 out of the M ay-J ul y 20 1 8 Incidents during the month related mainly to 37 members of the state Assembly. human trafficking and protests. According to Peace Map data (see Figure 1), Protests: In June, scores of women Child Trafficking: A 28-year old man and his incidents reported in the state during this protested at the Imo State government 30-year old wife reportedly sold three babies period included criminality, communal house in Owerri the state capital, over for six hundred thousand naira in Umuokai tensions, cult violence, political tensions, and frequent attacks by herdsmen in the area. -

Preliminary Interpretation of Gravity Mapping Over the Njaba Sub-Basin of Southeastern Nigeria: an Implication to Petroleum Potential

Vol. 5(3), pp.75-87, March, 2013 Journal of Geology and Mining DOI: 10.5897/JGMR2013.0171 ISSN 2006 – 9766 © 2013 Academic Journals Research http://www.academicjournals.org/JGMR Full Length Research Paper Preliminary interpretation of gravity mapping over the Njaba sub-basin of southeastern Nigeria: An implication to petroleum potential Ezekiel J. C.*, Onu N. N., Akaolisa C. Z. and Opara A. I. Department of Geosciences, Federal University of Technology, P. M. B. 1526, Owerri, Imo State, Nigeria. Accepted 29 March, 2013 Gravity data were acquired along two profiles in some parts of the Njaba River sub-basin. Profile A-A’ and B-B’ run for about 30 and 12 km respectively with the end of the two profiles meeting at Oguta Lake. The Bouguer gravity anomaly along Profile A-A’ revealed initial positive gravity values to a wavelength of about 21 km and then followed by a sudden drop of the observed gravity showing a significant gravity minimum. Profile B-B’ showed an alternating gravity high and low which was followed by a sudden extremely low value in the observed gravity. Further investigation showed that the structure modeled is graben and horsts bounded by two normal faults. The high gravity observed is due to the lesser density contrasts between the sediments and the basement which had resulted from the up-warping of the crust. The area showing low gravity revealed thick sedimentary accumulation of recently deposited alluvium deposits deposited in the subsided area bounded by these two faults. The structural framework of the parts of the sub-basin studied suggested an environment favorable for large scale entrapment of hydrocarbons. -

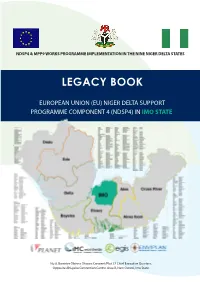

Ndsp4 Legacy Book 2019 (Imo State)

NDSP4 & MPP9 WORKS PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION IN THE NINE NIGER DELTA STATES LEGACY BOOK EUROPEAN UNION (EU) NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME COMPONENT 4 (NDSP4) IN IMO STATE No 8, Barrister Obinna Okwara Crescent/Plot 37 Chief Executive Quarters, Opposite Ahiajoku Convention Centre. Area B, New Owerri, Imo State. IMO STATE EUROPEAN UNION NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME NDSP4 LEGACY BOOK 2019 IMO STATE MAP MBAITOLI ISIALA MBANO IDEATO SOUTH EUROPEAN UNION NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME NDSP4 LEGACY BOOK 2019 IMO STATE Publication: NDSP4/013/09/2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD 4 PROGRAMME OVERVIEW 5 WORKS CONTRACT OVERVIEW 8 PROGRAMME IMPLEMENTATION TEAM 10 DETAILS OF NDSP4 PROGRAMME IN IMO STATE • STAKE HOLDERS TEAM 11 • PROJECT LIST 12 & 13 • PHOTOGRAPH OF IMPLEMENTED PROJECTS 14 Page 3 IMO STATE EUROPEAN UNION NIGER DELTA SUPPORT PROGRAMME NDSP4 LEGACY BOOK 2019 FOREWORD The NDSP4 Publication series is an attempt to bring some of our key reports and consultancy reports to our stakeholders and a wider audience. The overall objective of the Niger Delta Support Programme (NDSP) is to mitigate the conflict in the Niger Delta by addressing the main causes of the unrest and violence: bad governance, (youth) unemployment, poor delivery of basic services. A key focus of the programme will be to contribute to poverty alleviation through the development and support given to local community development initiatives. The NDSP4 aims to support institutional reforms and capacity building, resulting in Local Gov- ernment and State Authorities increasingly providing infrastructural services, income gener- ating options, sustainable livelihoods development, gender equity and community empow- erment. This will be achieved through offering models of transparency and participation as well as the involvement of Local Governments in funding Micro projects to enhance impact and sustainability. -

N Oguta Ke, Ngera

Socio-economic appraisal of cage fish culture in Oguta Lake, Nigeria Item Type conference_item Authors Okorie, P.U. Download date 28/09/2021 07:25:58 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/18755 SOCOECONOMC APPRASAL OF CAGE FSH CULTURE N OGUTA KE, NGERA BY PETER U. OKORIE Department ofAnimai and Environmental Biology, ltrwStateUniversity, IM.B.2000,Owerri, Nigeria. ABSTRAC'L (\gutalake is one of the largest natural lakes in south-eastern Nigeria.Traditionally, its fisheries support a large number of fill-time and part-time fishermen with their families. However, in recent years, like most other capture fisheries in Nigeria, fish yields have either been declining or stagnating. Fish stocks in the lake have for long been subjected to over-fishing and use of wrong fishing methods.. The paper proposes large-scale introduction of cage fish culture in the lake as a practical means of reducing fishing pressure on the lake as wellas providing a sustainable means of livelihood for the local population around the lake. Limnological characteristics of lake are described to appraise the feasibility of cage culture in the lake. Recommendations are made on the design, choice of materials, construction and management of cages in the lake. Cost-benefit projections based on prevailing market prices are presented. INTRODUCTION With a surface area of over 300 ha(Ita and Balogun, corresponding high fishing pressure on the lake. 1983), Lake Oguta is the largest natural lentie If this fishing pressure is allowed to continue, the system in the Imo river basin of southeastern fish yields fromthe lake will go into decline (if it Nigeria.