Queer Visions for a Post-Coal Appalachian Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Clones Stick Together

TVhome The Daily Home April 12 - 18, 2015 Clones Stick Together Sarah (Tatiana Maslany) is on a mission to find the 000208858R1 truth about the clones on season three of “Orphan Black,” premiering Saturday at 8 p.m. on BBC America. The Future of Banking? We’ve Got A 167 Year Head Start. You can now deposit checks directly from your smartphone by using FNB’s Mobile App for iPhones and Android devices. No more hurrying to the bank; handle your deposits from virtually anywhere with the Mobile Remote Deposit option available in our Mobile App today. (256) 362-2334 | www.fnbtalladega.com Some products or services have a fee or require enrollment and approval. Some restrictions may apply. Please visit your nearest branch for details. 000209980r1 2 THE DAILY HOME / TV HOME Sun., April 12, 2015 — Sat., April 18, 2015 DISH AT&T DIRECTV CABLE CHARTER CHARTER PELL CITY PELL ANNISTON CABLE ONE CABLE TALLADEGA SYLACAUGA BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM BIRMINGHAM CONVERSION CABLE COOSA SPORTS WBRC 6 6 7 7 6 6 6 6 AUTO RACING Friday WBIQ 10 4 10 10 10 10 6 p.m. FS1 St. John’s Red Storm at Drag Racing WCIQ 7 10 4 Creighton Blue Jays (Live) WVTM 13 13 5 5 13 13 13 13 Sunday Saturday WTTO 21 8 9 9 8 21 21 21 7 p.m. ESPN2 Summitracing.com 12 p.m. ESPN2 Vanderbilt Com- WUOA 23 14 6 6 23 23 23 NHRA Nationals from The Strip at modores at South Carolina WEAC 24 24 Las Vegas Motor Speedway in Las Gamecocks (Live) WJSU 40 4 4 40 Vegas (Taped) 2 p.m. -

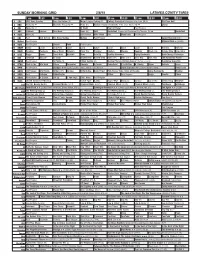

Sunday Morning Grid 4/12/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 4/12/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Bull Riding Remembers 2015 Masters Tournament Final Round. (N) Å 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Luna! Poppy Cat Tree Fu Figure Skating 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News Å Explore Incredible Dog Challenge 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program I Love Lucy I Love Lucy 13 MyNet Paid Program Red Lights ›› (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News TBA Things That Aren’t Here Anymore More Things Aren’t Here Anymore 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki Ad Dive, Olly Dive, Olly E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Toluca vs Atlas República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Best Praise Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Hocus Pocus ›› (1993) Bette Midler. -

P32.Qxp Layout 1 5/9/16 8:04 PM Page 1

p32.qxp_Layout 1 5/9/16 8:04 PM Page 1 TUESDAY, MAY 10, 2016 TV PROGRAMS List 04:36 Blood Relatives 00:50 South Park 05:24 Nowhere To Hide 00:20 Swamp People 20:50 David Rocco’s Dolce Vita 01:15 South Park 06:12 I Was Murdered 01:10 Appalachian Outlaws 21:15 David Rocco’s Dolce Vita 01:40 The Daily Show With Trevor 06:37 I Was Murdered 02:00 Ice Road Truckers 21:40 Valentine Warner Eats Noah 07:00 Blood Relatives 02:50 Ax Men Scandinavia 03:20 Fuzz 02:05 Dl Hughley: The Endangered 07:50 I Almost Got Away With It 22:05 The Food Files 04:50 Race For The Yankee List 08:40 Nowhere To Hide 22:30 Sara’s New Nordic Kitchen Zephyr 09:30 True Crime With Aphrodite 22:55 Food School 06:40 Hero’s Island Jones 23:20 Lee Chan’s World Food Tour 08:15 Breakin’ 10:20 I’d Kill For You 23:45 Mega Food 09:40 The Bridge In The Jungle 11:10 Deadline: Crime With Tamron 00:35 David Rocco’s Dolce Vita 11:05 Mirrormask Hall 03:25 Raised By Wolves 01:00 Chasing Time 12:45 Eight Men Out 12:00 Blood Relatives 03:55 Raised By Wolves 01:25 Miguel’s Feasts 12:50 I Almost Got Away With It 04:20 Doc Martin 01:50 The Food Files 14:45 The Crocodile Hunter: 03:00 Nightmare In Suburbia Collision Course 13:40 Nowhere To Hide 05:15 I’m A Celebrity...Get Me Out 02:15 Dream Cruises 04:00 Gangsters: America’s Most 14:30 True Crime With Aphrodite Of Here! 16:15 The Adventures Of Gerard Evil 17:45 Fuzz Jones 06:10 Coach Trip 05:00 Fred Dinenage: Murder 15:20 I Was Murdered 06:35 Catchphrase 19:15 Island Of The Lost Casebook 20:45 Big Screen 15:45 I Was Murdered 07:05 Callie-Anne -

Groundwork Humans & Nature Reader

Environmental Readings Volume 1: Humans Relationships With Nature Published by: Groundwork Education www.layinggroundwork.org Compiled & Edited by Jeff Wagner with help from Micaela Petrini, Caitlin McKimmy, Jason Shah, Parker Pflaum, Itzá Martinez de Eulate Lanza, Jhasmany Saavedra, & Dev Carey First Edition, June 2018 This work is comprised of articles and excerpts from numerous sources. Groundwork and the editors do not own the material or claim copyright or rights to this material, unless written by one of the editors. This work is distributed as a compilation of educational materials for the sole use as non-commercial educational material for educators. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free to edit and share this work in non-commercial ways. Any published derivative works must credit the original creator and maintain this same Creative Commons license. Please notify us of any derivative works or edits. Environmental Readings Volume 1: Human Relationships With Nature Published by Groundwork Education, compiled & edited by Jeff Wagner Skywoman Falling by Robin Wall Kimmerer .......................................................1 An alternative view: how to frame a relationship with the natural world that’s not just extractive and destructive. The Gospel of Consumption by Jeffrey Kaplan ....................................................4 What is the origin of our consumption-based society, and when did we make this choice as a people? Earthbound: On Solid Ground by bell hooks .......................................................9 “More than ever before in our nation’s history black folks must collectively renew our relationship to the earth…” Do we really love our land? by David James Duncan ..........................................11 What do people mean when they speak of “love of the land?” Most Americans claim to feel such a love. -

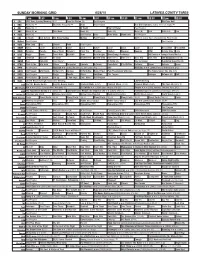

Sunday Morning Grid 2/8/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 2/8/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Major League Fishing (N) College Basketball Michigan at Indiana. (N) Å PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News (N) Hockey Chicago Blackhawks at St. Louis Blues. (N) Å Skiing 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC Outback Explore This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Clippers at Oklahoma City Thunder. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Larger Than Life ›› 13 MyNet Paid Program Material Girls › (2006) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local Transfor. Transfor. 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Chefs Life Simply Ming Ciao Italia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Biz Healthy Hormones Aging Backwards BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Karate Kid Part II 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Mexico Primera Division Soccer: Pumas vs Leon República Deportiva 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. -

Tenino Parade Celebrates Completion of Capstones

Stepping Up for Cure The Agony of / Main 14 Lewis County Firefighters Train for Massive Stair Climb / Life 1 Defeat $1 Early Week Edition Tuesday, Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Feb. 3, 2015 Hot-Handed Ony National Problem Loggers Down Mules as C2BL Teams Local Frozen Food Company Hampered Jockey for Playoff Positioning / Sports 2 by Ongoing Port Slowdown / Main 3 Broker County Hopes to Recoup $800,000 Breaks Investment in Former Ammo Plant Super Bowl FINANCIAL IMPACT: Nosler The sudden closure of a Lewis County commission- nition manufacturer that ended Dreams Packwood ammunition factory ers in 2009 approved a loan of up being bought by Nosler of Will Pay on Lease for Two in January not only left 17 peo- $300,000 — which later be- Bend, Oregon, in 2013. More Years After Closing ple searching for a job, but it has came a grant — and another Nosler shuttered the plant for County Packwood Facility Lewis County officials looking for $800,000 to improve and in January, leaving buildings into how they can recoup their build two separate buildings at tailor-made for manufactur- Assessor By Christopher Brewer investment into the facility on a the Packwood Business Park for ing suddenly unused. The East [email protected] long-term basis. Silver State Armory, an ammu- please see AMMO, page Main 12 OUT OF LUCK: Centralia Woman Hoped to Attend Big Game, But Super Bowl Tickets Never Materialized Tenino Parade Celebrates By Dameon Pesanti [email protected] Dianne Dorey bought her Super Bowl tickets less than Completion of Capstones five minutes after the Se- ahawks won the NFC Champi- onship Game. -

Three Rivers THREERIVERSNEWS.COM

Stephenson named MONDAY, OCTOBER 17, 2016 Historian of the Year... Since 1895 –page 2 Vol. 122, Issue #246 75¢ Three Rivers THREERIVERSNEWS.COM COMMERCIAL-NEWS Commander speaks Larry Money (right), Michigan State Commander of the American Legion, speaks at a gravestone dedication service for Pvt. Augustus Smith (gravestone left) and Pvt. Stephen Corwin (gravestone second from left). Next to Money is Jon Mieras, service officer of the Constantine American Legion Post #223. Commercial-News/Elena Meadows ‘Today we will right that wrong’ their country,” Jon Mieras, service officer buried in this cemetery without after their marriage. Corwin then moved October 1863. His unit was attached to Two 19th-century of the Constantine American Legion gravestones to mark their resting places to Mendon and married Mary Butts on District of Lexington, Ky., 23rd Army veterans get Post #223, told the audience at a to be forgotten for almost one hundred Nov. 16, 1858. He had at least four Corps, Army of the Ohio, to April 1864. gravestone dedication service for Pvt. years. Today we will right that wrong and children with his first two wives. Mary First Brigade, First Division, District of headstones Stephen Corwin and Pvt. Augustus will honor these brave men as should also passed away at a young age. Corwin Kentucky, 5th Division, 23rd Army By Elena Meadows Smith Sunday, Oct. 16 at Brick Chapel have been done all those years ago.” married for a third time; his third wife Corps, Department of the Ohio, to Managing Editor Cemetery. “Men who suffered the Corwin was born in Wayne County, was Lucinda Forman and they had two August 1864. -

Free $40 Book

PAID ECRWSS Eagle River PRSRT STD PRSRT U.S. Postage Permit No. 13 Stk# 8020 POSTAL PATRON POSTAL Stk# 1013 Stk# 5059 Stk# 3578 * ** * ** 6,661 5,000 6,801 $ $ $ 33,789 $ 27,498 63,504 33,337 29,849 $ $ Saturday, Saturday, $ $ 26,974 $ Oct. 15, 2016 15, Oct. (715) 479-4421 2016 Chevy Suburban LTZ 2015 Buick Lacrosse AND THE THREE LAKES NEWS TAILGATE SALE SPECIALS: TAILGATE PRICE PRICE 2015 Chevy Silverado LT Crew Cab 4WD 2007 Chevy Silverado Crew Cab Diesel Retail INTERNET Retail INTERNET Leather, 2,814 miles Leather, $36,650 MSRP Parsons Discount SALE PRICE $75,165 MSRP Parsons Discount Rebate SALE PRICE Stk# 5684 Stk# 8320 Stk# 4313 Stk# 8970 A SPECIAL SECTION OF THE VILAS COUNTY NEWS-REVIEW THE VILAS COUNTY SECTION OF SPECIAL A * * ** ** 7,594 8,251 6,943 $ $ $ 32,987 36,673 $ $ 66,665 26,072 GM CERTIFIED: 35,487 31,897 $ $ MSRP $33,015 MSRP $ $ **Plus tax, title, license and $149 Dealer doc fee. 2015 Chevy Impala LT 2016 Corvette Stingray Convertible PRICE PRICE 2012 Chevy LT Tahoe 2013 Chevy Avalanche Advanced Safety Pkg., heated seats MSRP $82,510 MSRP Parsons Discount Rebate SALE PRICE 2,955 miles Parsons Discount SALE PRICE Retail INTERNET Retail INTERNET Stk# 7198 THESE NEW 2016 MODELS MUST GO! Stk# 3013 Stk# 2167 Stk# 1512 2016 Tahoe *Plus tax, title, license, $40 Nitrogen Fill and $149 Dealer document fee. Some customers may be eligible for additional rebates. See Parsons for info and details. TAILGATE SALE TAILGATE * * ** ** NORTH WOODS NORTH THE PAUL BUNYAN OF NORTH WOODS ADVERTISING WOODS OF NORTH BUNYAN THE PAUL 996 7,215 1,500 $ $ $ 31,895 $ 53,755 15,999 24,684 30,895 $ $ $ $ 23,998 $ RETIRED COURTESY TRANSPORTATION VEHICLES “SOLD AS NEW” TRANSPORTATION RETIRED COURTESY 2016 Chevy Cruze GOLD CHECK CERTIFIED: PRICE PRICE 2015 Subaru XV Crosstrek AWD 2015 Ford Explorer Limited 4WD Luxury Package, Navigation, V8, 4,564 miles MSRP $62,470 MSRP Parsons Discount Rebate SALE PRICE MSRP $16,995 MSRP Parsons Discount SALE PRICE Retail INTERNET Retail INTERNET © Eagle River Publications, Inc. -

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015

The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. 12/29/14-12/27/15. Original telecasts only. Excludes repeats, specials, movies, news, sports, programs with only one telecast, and Spanish language nets. Cable: Mon-Sun, 8-11P. Broadcast: Mon-Sat, 8-11P; Sun 7-11P. "<<" denotes below Nielsen minimum reporting standards based on P2+ Total U.S. Rating to the tenth (0.0). Important to Note: This list utilizes the TV Guide listing service to denote original telecasts (and exclude repeats and specials), and also line-items original series by the internal coding/titling provided to Nielsen by each network. Thus, if a network creates different "line items" to denote different seasons or different day/time periods of the same series within the calendar year, both entries are listed separately. The following provides examples of separate line items that we counted as one show: %(7 V%HLQJ0DU\-DQH%(,1*0$5<-$1(6DQG%(,1*0$5<-$1(6 1%& V7KH9RLFH92,&(DQG92,&(78( 1%& V7KH&DUPLFKDHO6KRZ&$50,&+$(/6+2:3DQG&$50,&+$(/6+2: Again, this is a function of how each network chooses to manage their schedule. Hence, we reference this as a list as opposed to a ranker. Based on our estimated manual count, the number of unique series are: 2015³1,415 primetime series (1,524 line items listed in the file). 2014³1,517 primetime series (1,729 line items). The List: All Primetime Series on Television Calendar Year 2015 Source: Nielsen, Live+7 data provided by FX Networks Research. -

Equitable Solutions for Poverty Poaching of Venus Flytraps

Washington Journal of Environmental Law & Policy Volume 8 Issue 2 7-1-2018 Trapped in the Goddess's Mousetrap: Equitable Solutions for Poverty Poaching of Venus Flytraps Katrina Outland Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wjelp Part of the Natural Resources Law Commons Recommended Citation Katrina Outland, Notes and Comments, Trapped in the Goddess's Mousetrap: Equitable Solutions for Poverty Poaching of Venus Flytraps, 8 WASH. J. ENVTL. L. & POL'Y 362 (2018). Available at: https://digitalcommons.law.uw.edu/wjelp/vol8/iss2/5 This Notes and Comments is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Reviews and Journals at UW Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington Journal of Environmental Law & Policy by an authorized editor of UW Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Outland: Trapped in the Goddess's Mousetrap: Equitable Solutions for Pover Copyright © 2018 by Washington Journal of Environmental Law & Policy TRAPPED IN THE GODDESS’S MOUSETRAP: EQUITABLE SOLUTIONS FOR POVERTY POACHING OF VENUS FLYTRAPS Katrina Outland1 Abstract Most discussions of poaching—the intentional, unlawful taking or killing of a living organism—focus on animals. However, poaching is also the primary threat for many prized collectible plants. The bizarre Venus flytrap has particularly drawn media attention as North Carolina struggles to save its endemic State Carnivorous Plant from extinction. Existing federal plant protection laws are sparse and either ineffective (in the case of the Endangered Species Act) or underutilized (in the case of the Lacey Act). Traditional poaching enforcement methods, which target individual poachers with small fines, are designed for animal poaching, and fail to adequately protect plants. -

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 ______

Appalachian Studies Bibliography Cumulation 2013-June 2016 _____________________ CONTENTS Agriculture and Land Use ................................................................................................................3 Appalachian Studies.........................................................................................................................8 Archaeology and Physical Anthropology ......................................................................................14 Architecture, Historic Buildings, Historic Sites ............................................................................18 Arts and Crafts ..............................................................................................................................21 Biography .......................................................................................................................................27 Civil War, Military.........................................................................................................................29 Coal, Industry, Labor, Railroads, Transportation ..........................................................................37 Description and Travel, Recreation and Sports .............................................................................63 Economic Conditions, Economic Development, Economic Policy, Poverty ................................71 Education .......................................................................................................................................82 -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/28/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/28/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Paid Program Red Bull Signature Series From Las Vegas. Å 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) News (N) News (N) Paid Vista L.A. Paid 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Hour Mike Webb Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Golf U.S. Senior Open Championship, Final Round. 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Man Land Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dowdle Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking BBQ Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight BrainChange-Perlmutter 30 Days to a Younger Heart-Masley 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly The Bodyguard ›› (R) 34 KMEX Paid Conexión Paid Program Al Punto (N) Tras la Verdad República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program Madison ›› (2001) Jim Caviezel, Jake Lloyd.