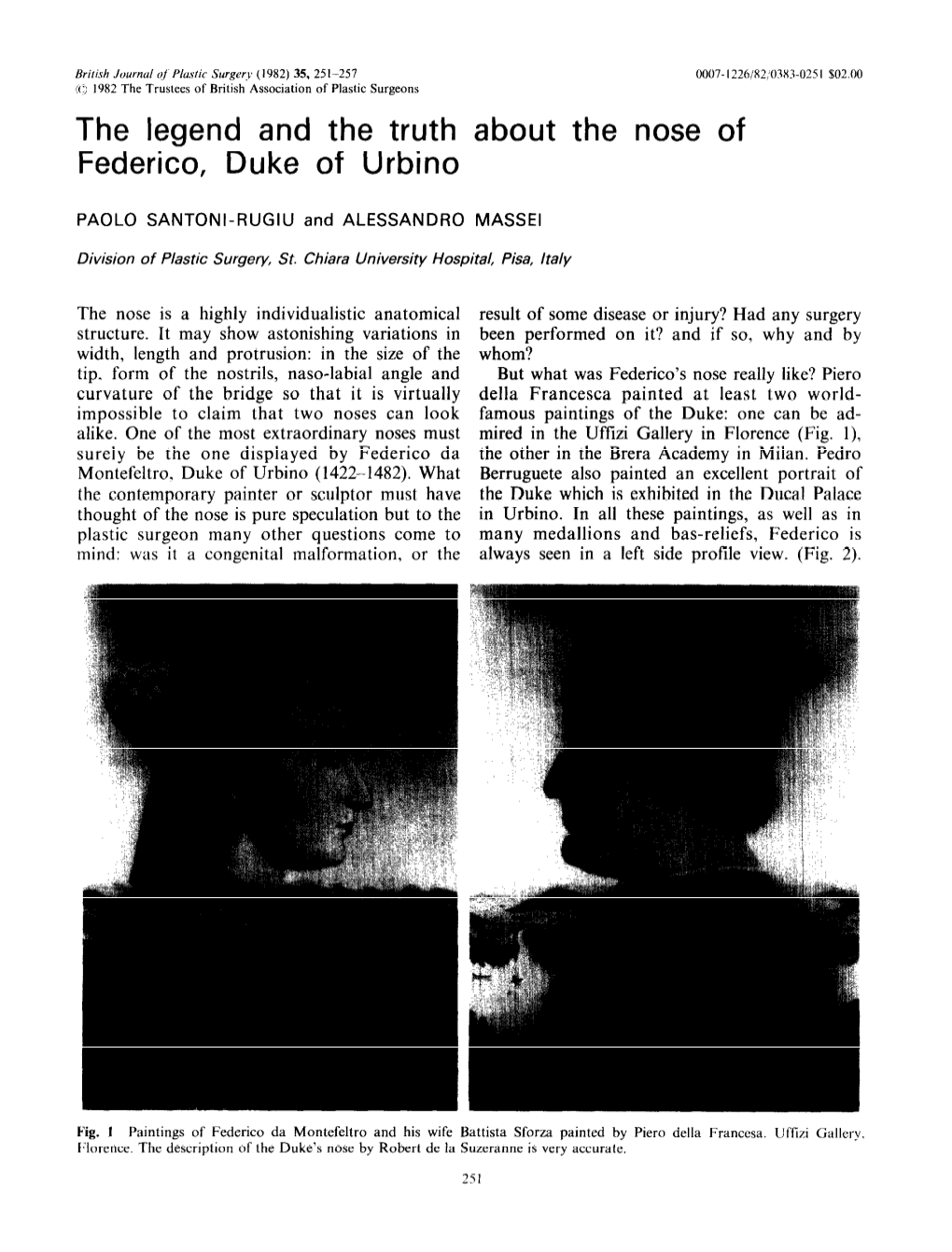

The Legend and the Truth About the Nose of Federico, Duke of Urbino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

I Primi 3 Servizi Selezionati Come Prioritari Sono

PROVINCIA DI PESARO E URBINO SERVIZI PROVINCIALI PER IL TERRITORIO Indagine conoscitiva sulla domanda di servizi provinciali per il territorio (Funzioni di supporto tecnico – amministrativo agli Enti Locali) - Analisi dei primi risultati – A tutti i 59 comuni del territorio della Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino è stato sottoposto un questionario on-line contenente l’elenco di tutti i servizi offerti, raggruppati in aree e gruppi tematici. I comuni hanno espresso la propria domanda selezionando i servizi di interesse, con la possibilità di segnalare, per ogni gruppo, un servizio di valenza prioritaria. Nel territorio sono presenti 10 Comuni con popolazione tra 5.000 e 10.000 abitanti e 7 di questi Comuni hanno espresso le loro necessità, il 70% di loro ha compilato il questionario. Per quanto riguarda i Comuni più grandi, al di sopra dei 10.000 abitanti, 3 su 5 hanno segnalato i servizi utili alla loro realtà comunale. 3 su 5 corrisponde al 60% dei Comuni medio-grandi. DATI COPERTURA INDAGINE hanno risposto 43 comuni su 59 pari al 73% I comuni rispondenti suddivisi per fascia demografica (numero residenti) 7% 16% 77% <=5000 >5000 e <=10000 >=10000 Fascia di Comuni Comuni totali % rispondenti popolazione rispondenti per fascia (n° residenti) <=5000 33 44 75% >5000 e <=10000 7 10 70% >=10000 3 5 60% Totale 43 69 73% Fonte: Sistema Informativo e Statistico Elaborazione: Ufficio 5.0.1 - Gestione banche dati, statistica, sistemi informativi territoriali e supporto amministrativo 1 PROVINCIA DI PESARO E URBINO SERVIZI PROVINCIALI PER IL TERRITORIO QUADRO GENERALE 8 aree funzionali 20 gruppi di servizi Per un totale di 119 singoli servizi offerti Domanda di servizi espressa dai comuni del territorio In ordine decrescente su 119 servizi presenti nell'elenco dei servizi presentati in sede di assemblea dei Sindaci, il massimo numero di servizi richiesti per Comune è 91 con una media di 31 servizi complessivi per ogni Comune che possono essere confermati o implementati come nuovi. -

Motorway A14, Exit Pesaro-Urbino • Porto Di Ancona: Croatia, Greece, Turkey, Israel, Ciprus • Railway Line: Milan, Bologna, Ancona, Lecce, Rome, Falconara M

CAMPIONATO D’EUROPA FITASC – FINALE COPPA EUROPA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP San Martino/ Rio Salso di Tavullia – Pesaro/Italia, 17/06/2013 – 24/06/2013 • Motorway A14, exit Pesaro-Urbino • Porto di Ancona: Croatia, Greece, Turkey, Israel, Ciprus • Railway Line: Milan, Bologna, Ancona, Lecce, Rome, Falconara M. • AIRPORT: connection with Milan, Rom, Pescara and the main European capitals: Falconara Ancona “Raffaello Sanzio” 80 KM da Pesaro Forlì L. Ridolfi 80 KM da Pesaro Rimini “Federico Fellini” 30 KM da Pesaro Bologna “Marconi” 156 KM da Pesaro CAMPIONATO D’EUROPA FITASC – FINALE COPPA EUROPA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP San Martino/ Rio Salso di Tavullia – Pesaro/Italia, 17/06/2013 – 24/06/2013 Rossini tour: Pesaro Pesaro was the birth place of the famous musician called “Il Cigno di Pesaro” A walk through the characteristic streets of the historic centre lead us to Via Rossini where the Rossini House Museum is situated. It is possible to visit his house, the Theatre and the Conservatory that conserve Rossini’s operas and memorabilia. Prices: Half Day tour: € 5.00 per person URBINO URBINO is the Renaissance of the new millennium. Its Ducal Palce built for the grand duke Federico da Montefeltro, with its stately rooms, towers and magnificent courtyard forms a perfect example of the architecture of the time. Today , the building still houses the Galleria Nazionale delle Marche with precious paintings by Piero della Francesca, Tiziano, Paolo Uccello and Raphael, whose house has been transformed into a museum. Not to be missed, are the fifteenth century frescoes of the oratory of San Giovanni and the “Presepio” or Nativity scene of the Oratory of San Giuseppe (entry of Ducal Palace, Oratories) Prices: Half Day tour: € 25.00 per person included: bus - guide – Palazzo Ducale ticket – Raffaello Sanzio’s birthplace ticket CAMPIONATO D’EUROPA FITASC – FINALE COPPA EUROPA EUROPEAN CHAMPIONSHIP San Martino/ Rio Salso di Tavullia – Pesaro/Italia, 17/06/2013 – 24/06/2013 REPUBLIC OF SAN MARINO This is one of the smallest and most interesting Republics in the world. -

DISCOVERING LE MARCHE REGION Detailed Itinerary

DISCOVERING LE MARCHE REGION Departure: 16 June - 23 June 2021 (8 days/7 nights) The tour provides an excellent opportunity to experience the life in Italy’s best kept secret tourist destination: Le Marche Region, nestled between the Apennines and the Adriatic Sea. This tour leads you to fascinating hill towns vibrant with daily life surrounded by beautiful countryside. You will leisurely wander through cobbled streets and magnificent town piazze. The relaxed itinerary will allow time to enjoy the life on the Adriatic. The tour starts in Rome. There will be a relaxed walking tour of some of the main sites of Rome followed by an introductory dinner. Then it is off to the City of Pesaro in Le Marche Region, your home for the next 7 nights. From this base, guided day trips are organised to historical towns such as Urbino, Gradara and San Leo. One of the highlights will be a day in the Medieval town of Urbania for a unique cooking demonstration followed by a degustation lunch in an award winning osteria. You will have the possibility to experience the excellent hospitality of this beautiful Region which rivals its neighbours with its abundance of traditional local food and wine. You will enjoy leisurely lunches and special dinners in traditional restaurants and trattorie. This tour gives you the opportunity to enjoy the summer season when the entire Region is alive with music, markets and life. Detailed Itinerary Day 1 Rome (D) Your tour leaders will meet you at the hotel in the centre of Rome at 4.00pm. -

Discovery Marche.Pdf

the MARCHE region Discovering VADEMECUM FOR THE TOURIST OF THE THIRD MILLENNIUM Discovering THE MARCHE REGION MARCHE Italy’s Land of Infinite Discovery the MARCHE region “...For me the Marche is the East, the Orient, the sun that comes at dawn, the light in Urbino in Summer...” Discovering Mario Luzi (Poet, 1914-2005) Overlooking the Adriatic Sea in the centre of Italy, with slightly more than a million and a half inhabitants spread among its five provinces of Ancona, the regional seat, Pesaro and Urbino, Macerata, Fermo and Ascoli Piceno, with just one in four of its municipalities containing more than five thousand residents, the Marche, which has always been Italyʼs “Gateway to the East”, is the countryʼs only region with a plural name. Featuring the mountains of the Apennine chain, which gently slope towards the sea along parallel val- leys, the region is set apart by its rare beauty and noteworthy figures such as Giacomo Leopardi, Raphael, Giovan Battista Pergolesi, Gioachino Rossini, Gaspare Spontini, Father Matteo Ricci and Frederick II, all of whom were born here. This guidebook is meant to acquaint tourists of the third millennium with the most important features of our terri- tory, convincing them to come and visit Marche. Discovering the Marche means taking a path in search of beauty; discovering the Marche means getting to know a land of excellence, close at hand and just waiting to be enjoyed. Discovering the Marche means discovering a region where both culture and the environment are very much a part of the Made in Marche brand. 3 GEOGRAPHY On one side the Apen nines, THE CLIMATE od for beach tourism is July on the other the Adriatic The regionʼs climate is as and August. -

Routing Sheet

LC 265 RENAISSANCE ITALY (IT gen ed credit) for May Term 2016: Tentative Itinerary Program Direction and Academic Content to be provided by IWU Professor Scott Sheridan Contact [email protected] with questions! 1 Monday CHICAGO Departure. Meet at Chicago O’Hare International Airport to check-in for May 2 departure flight for Rome. 2 Tuesday ROME Arrival. Arrive (09.50) at Rome Fiumicino Airport and transfer by private motorcoach, May 3 with local assistant, to the hotel for check-in. Afternoon (13.00-16.00) departure for a half- day walking tour (with whisperers) of Classical Rome, including the Colosseum (entrance at 13.40), Arch of Constantine, Roman Forum (entrance), Fori Imperiali, Trajan’s Column, and Pantheon. Gelato! Group dinner (19.30). (D) 3 Wednesday ROME. Morning (10.00) guided tour (with whisperers) of Vatican City including entrances to May 4 the Vatican Rooms and Sistine Chapel. Remainder of afternoon at leisure. Evening (20.30) performance of Accademia d’Opera Italiana at All Saints Church. (B) 4 Thursday ROME. Morning (09.00) departure for a full-day guided walking tour including Piazza del May 5 Campidoglio, Palazzo dei Conservatori, Musei Capitolini (entrance included at 10.00), the Piazza Venezia, Circus Maximus, Bocca della Verità, Piazza Navona, Piazza Campo de’ Fiori, Piazza di Spagna and the Trevi Fountain. (B) 1 5 Friday ROME/RAVENNA. Morning (07.45) departure by private motorcoach to Ravenna with en May 6 route tour of Assisi with local guide, including the Basilica (with whisperers) and the Church of Saint Claire. Check-in at the hotel. -

Documento Agcom

DOCUMENTO INFORMATIVO COMPLETO (in ottemperanza all’art. 5 del Regolamento in materia di pubblicazione e diffusione dei sondaggi sui mezzi di comunicazione di massa approvato dall’Autorità per le garanzie nelle comunicazioni con delibera n. 256/10/CSP, pubblicata su GU n. 301 del 27/12/2010) 1. TITOLO DEL SONDAGGIO Ø “Sblocca Italia e trivellazioni: l’opinione dei marchigiani” 2. SOGGETTO CHE HA REALIZZATO IL SONDAGGIO Ø Sigma Consulting di Marco Coltro e Alberto Paterniani snc 3. SOGGETTO COMMITTENTE Ø Sigma Consulting di Marco Coltro e Alberto Paterniani snc 4. SOGGETTO ACQUIRENTE Ø Sigma Consulting di Marco Coltro e Alberto Paterniani snc 5. PERIODO IN CUI È STATO REALIZZATO IL SONDAGGIO Ø 12 – 16 ottobre 2015 6. MEZZI DI COMUNICAZIONE DI MASSA SUI QUALI È PUBBLICATO/DIFFUSO IL SONDAGGIO Ø Pubblicato e diffuso da agenzie di stampa e quotidiani/periodici cartacei e online tra i quali il Corriere Adriatico e http://laprovinciadifermo.com/ 7. DATA DI PUBBLICAZIONE/DIFFUSIONE Ø 30 novembre 2015 8. TEMI OGGETTO DEL SONDAGGIO Ø Sondaggio sull’opinione dei marchigiani in merito alle trivellazioni in Adriatico previste dal decreto “Sblocca Italia” Sigma Consulting Via del Cinema, 5 Tel: +39 0721 415210 [email protected] P. IVA e C.F: 02419420415 61122 - Pesaro Fax: +39 0721 1622038 sigmaconsulting.biz 9. POPOLAZIONE DI RIFERIMENTO Ø Popolazione maggiorenne residente nella Regione Marche 10. ESTENSIONE TERRITORIALE DEL SONDAGGIO Ø Intero territorio regionale. Elenco dei comuni della regione Marche nei quali è stata realizzata almeno -

THE BEST of TUSCANY, UMBRIA & LE MARCHE Detailed Itinerary

THE BEST OF TUSCANY, UMBRIA & LE MARCHE Departure: 24 September - 6 October 2020 (13 Days/12 Nights) The rolling hills of Tuscany, Umbria and Le Marche are dotted with vineyards and olive groves. This area of Italy is famous for being known as, the ‘Green Heart’ of the Peninsula. Each region has its own particular character offering spectacular scenery, authentic cuisine and romantic hill towns. It is also a journey from the Medieval period to one of the most splendid eras of European civilization: The Renaissance. The experience starts in Rome where you will see works by the greatest masters of the period who were commissioned by the Bishops of Rome. The tour ends where it all started in Florence, the home of the Medici. Between these two highlights, there will be guided tours to explore the treasures and experience the life in centres such as Urbino, Gubbio, Loreto, Assisi, Perugia, San Gimignano, Volterra and Siena. Your tour leaders, Mario, Viny and Gianni complement the tour with their intimate knowledge of the history, culture and Italian way of life. We will give you the opportunity to experience the excellent hospitality of the people of Central Italy with its abundance of traditional local food and wine. You will enjoy leisurely lunches and special dinners in traditional restaurants and osterie. There are also opportunities to shop at local markets and speciality shops. Detailed Itinerary Day 1 Rome (D) Your tour leaders will meet you at the Hotel in the centre of Rome at 4.00pm. Introductions and a small talk on the tour will precede an afternoon walk through some of the famous iconic areas of Rome. -

Comunità Montana Alto Medio Metauro Provincia Di Pesaro E Urbino Al Corpo Forestale Dello Stato Comando Stazione Di Mercatello Sul Metauro

Comunità Montana Alto Medio Metauro Provincia di Pesaro e Urbino Al Corpo Forestale dello Stato Comando Stazione di Mercatello sul Metauro Codice richiesta: 202C_12/13 Data richiesta: 28/12/2012 DENUNCIA DI INIZIO LAVORI per il taglio dei soli boschi cedui Il sottoscritto GIANFRANCO GIACCIOLI, in qualità di PROPRIETARIO, nato a MERCATELLO SUL METAURO il 12/12/1943, residente a MERCATELLO SUL METAURO in via DELLA FORNACE 7 tel. NESSUNO, ai sensi ed agli effetti dell’art. 47 del D.P.R. 28 Dicembre 2000 n. 445, consapevole delle sanzioni penali cui può andare incontro in caso di dichiarazioni mendaci, e della decadenza dei benefici eventualmente conseguenti al provvedimento emanato sulla base della dichiarazione non veritiera COMUNICA - l'inizio lavori di taglio di bosco ceduo a regime (non invecchiato), per una superficie pari od inferiore ad Ha 02.00.00. - Data inizio lavori 28/01/2013; - Data fine lavori 15 Aprile 2014 DICHIARA altresì: - il taglio è richiesto per uso DOMESTICO - il taglio sarà eseguito conformemente alle vigenti Prescrizioni di Massima ed alla D.G.R. n. 2585/01, nel rispetto dell’obbligo di rilasciare una pianta destinata all’invecchiamento indefinito per ogni tagliata superiore a 2000 mq come da art. 24; - il bosco è sito in Comune di MERCATELLO SUL METAURO, Loc. VAL DELLA TANA, denominato LAGO LUNGOdell’età di 23 anni e della superficie complessiva di Ha , - matricine ad ettaro presenti: < 180, - altitudine 500 - 1000 m s.l.m., - periodo di taglio dal 1 Ottobre al 15 Aprile, - tipo esbosco MEZZO MECCANICO, - la specie legnosa predominante è CARPINo; le specie secondarie sono CERRO-ORNIELLO, la massa legnosa presunta ricavabile dal taglio è di 150 Q, le vie di accesso più vicine sono: STRADA VICINALE DELLE FIENAIE, il taglio verrà eseguito dalla ditta IN PROPRIO residente in Comune di , l’imposto verrà realizzato in località SUL POSTO del Comune di MERCATELLO SUL METAURO, - estremi catastali della superficie da sottoporre a taglio: Comune Foglio Particella Superficie tot. -

Microsoft Word Viewer 97

COPIA dell’ORIGINALE Deliberazione N. 146 / 2008 Estratto dal verbale delle deliberazioni di Giunta OGGETTO: ATTUAZIONE L.R. 26/98 "ISTITUZIONE PARCHI URBANI" - PROGRAMMA PROVINCIALE ANNO 2006 - MODIFICA DEL PROGRAMMA APPROVATO CON DELIBERA DI GIUNTA PROVINCIALE N. 450 DEL 22.12.2006. L’anno duemilaotto il giorno otto del mese di Maggio alle ore 08:30 in Pesaro nella sala delle adunanze “Sara Levi Nathan”. A seguito di avvisi, si è riunita la Giunta Provinciale nelle persone dei Signori: UCCHIELLI PALMIRO Presidente Presente RONDINA GIOVANNI Vice Presidente Presente CAPPONI SAURO Assessore Presente GALUZZI MASSIMO Assessore Presente ILARI GRAZIANO Assessore Presente LUCARINI GIUSEPPE Assessore Presente ROMAGNA SIMONETTA Assessore Presente SAVELLI RENZO Assessore Assente SORCINELLI PAOLO Assessore Presente Assiste il Segretario Generale RONDINA ROBERTO . Riconosciuta legale l’adunanza il Sig. UCCHIELLI PALMIRO , assunta la Presidenza, invita i Membri della Giunta stessa a prendere in trattazione i seguenti oggetti: (OMISSIS) Pag. 1 Deliberazione N. 146 / 2008 IL DIRIGENTE DEL SERVIZIO 4.1. URBANISTICA – PIANIFICAZIONE TERRITORIALE PREMESSO che la L.R. n. 26/98 stabilisce che le Province collaborino con la Regione Marche, secondo criteri di sussidiarietà, per la valorizzazione ambientale delle aree urbane mediante la realizzazione di parchi urbani, favorendo il contestuale risanamento di aree in situazione di degrado ambientale. VISTA e condivisa la relazione della P.O. 4.1.1 Pianificazione Territoriale - VIA - Beni Paesistico Ambientali prot. n. 31801/08 del 30 aprile 2008, che qui di seguito si riporta: ““ 1.PREMESSA La Regione Marche, con Delibera di G.R. n. 364 del 3 aprile 2006, pubblicata sul BUR n. 39 del 14 aprile 2006, ha stabilito che le risorse finanziarie disponibili per l’anno 2006 per l’attuazione della L.R. -

Patronage and Dynasty

PATRONAGE AND DYNASTY Habent sua fata libelli SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES SERIES General Editor MICHAEL WOLFE Pennsylvania State University–Altoona EDITORIAL BOARD OF SIXTEENTH CENTURY ESSAYS & STUDIES ELAINE BEILIN HELEN NADER Framingham State College University of Arizona MIRIAM U. CHRISMAN CHARLES G. NAUERT University of Massachusetts, Emerita University of Missouri, Emeritus BARBARA B. DIEFENDORF MAX REINHART Boston University University of Georgia PAULA FINDLEN SHERYL E. REISS Stanford University Cornell University SCOTT H. HENDRIX ROBERT V. SCHNUCKER Princeton Theological Seminary Truman State University, Emeritus JANE CAMPBELL HUTCHISON NICHOLAS TERPSTRA University of Wisconsin–Madison University of Toronto ROBERT M. KINGDON MARGO TODD University of Wisconsin, Emeritus University of Pennsylvania MARY B. MCKINLEY MERRY WIESNER-HANKS University of Virginia University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee Copyright 2007 by Truman State University Press, Kirksville, Missouri All rights reserved. Published 2007. Sixteenth Century Essays & Studies Series, volume 77 tsup.truman.edu Cover illustration: Melozzo da Forlì, The Founding of the Vatican Library: Sixtus IV and Members of His Family with Bartolomeo Platina, 1477–78. Formerly in the Vatican Library, now Vatican City, Pinacoteca Vaticana. Photo courtesy of the Pinacoteca Vaticana. Cover and title page design: Shaun Hoffeditz Type: Perpetua, Adobe Systems Inc, The Monotype Corp. Printed by Thomson-Shore, Dexter, Michigan USA Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Patronage and dynasty : the rise of the della Rovere in Renaissance Italy / edited by Ian F. Verstegen. p. cm. — (Sixteenth century essays & studies ; v. 77) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-1-931112-60-4 (alk. paper) ISBN-10: 1-931112-60-6 (alk. paper) 1. -

Italian Sixteenth-Century Maiolica Sanctuaries and Chapels

religions Article Experiencing La Verna at Home: Italian Sixteenth-Century Maiolica Sanctuaries and Chapels Zuzanna Sarnecka The Institute of Art History, University of Warsaw, 00-927 Warszawa, Poland; [email protected] Received: 30 September 2019; Accepted: 17 December 2019; Published: 20 December 2019 Abstract: The present study describes the function of small-scale maiolica sanctuaries and chapels created in Italy in the sixteenth century. The so-called eremi encouraged a multisensory engagement of the faithful with complex structures that included receptacles for holy water, openings for the burning of incense, and moveable parts. They depicted a saint contemplating a crucifix or a book in a landscape and, as such, they provided a model for everyday pious life. Although they were less lifelike than the full-size recreations of holy sites, such as the Sacro Monte in Varallo, they had the significant advantage of allowing more spontaneous handling. The reduced scale made the objects portable and stimulated a more immediate pious experience. It seems likely that they formed part of an intimate and private setting. The focused attention given here to works by mostly anonymous artists reveals new categories of analysis, such as their religious efficacy. This allows discussion of these neglected artworks from a more positive perspective, in which their spiritual significance, technical accomplishment and functionality come to the fore. Keywords: Italian Renaissance; devotion; home; La Verna; sanctuaries; maiolica; sculptures; multisensory experience 1. Introduction During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, ideas about religious sculpture still followed two conflicting trains of thought. On the one hand, writers understood the efficacy of both sculptural and painted images at impressing the divine image onto the mind and soul of the beholder. -

Italy Travel and Driving Guide

Travel & Driving Guide Italy www.autoeurope. com 1-800-223-5555 Index Contents Page Tips and Road Signs in Italy 3 Driving Laws and Insurance for Italy 4 Road Signs, Tolls, driving 5 Requirements for Italy Car Rental FAQ’s 6-7 Italy Regions at a Glance 7 Touring Guides Rome Guide 8-9 Northwest Italy Guide 10-11 Northeast Italy Guide 12-13 Central Italy 14-16 Southern Italy 17-18 Sicily and Sardinia 19-20 Getting Into Italy 21 Accommodation 22 Climate, Language and Public Holidays 23 Health and Safety 24 Key Facts 25 Money and Mileage Chart 26 www.autoeurope.www.autoeurope.com com 1-800 -223-5555 Touring Italy By Car Italy is a dream holiday destination and an iconic country of Europe. The boot shape of Italy dips its toe into the Mediterranean Sea at the southern tip, has snow capped Alps at its northern end, and rolling hills, pristine beaches and bustling cities in between. Discover the ancient ruins, fine museums, magnificent artworks and incredible architecture around Italy, along with century old traditions, intriguing festivals and wonderful culture. Indulge in the fantastic cuisine in Italy in beautiful locations. With so much to see and do, a self drive holiday is the perfect way to see as much of Italy as you wish at your own pace. Italy has an excellent road and highway network that will allow you to enjoy all the famous sites, and give you the freedom to uncover some undiscovered treasures as well. This guide is aimed at the traveler that enjoys the independence and comfort of their own vehicle.