Download (1MB)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of 36 POLICY 117.1 UNIFORMS, ATTIRE and GROOMING REVISED

POLICY UNIFORMS, ATTIRE AND GROOMING 117.1 REVISED: 1/93, 10/99, 12/99, 07/01, RELATED POLICIES: 405, 101, 101.1 04/02, 1/04, 08/04, 12/05, 03/06, 03/07, 05/10, 02/11, 06/11, 11/11, 07/12, 04/13, 01/14, 08/15, 06/16, 06/17, 03/18, 09/18, 03/19, 03/19, 04/21,07/21,08/21 CFA STANDARDS: REVIEWED: As Needed TABLE OF CONTENTS A. PURPOSE .............................................................................................................................. 1 B. GENERAL ............................................................................................................................. 2 C. UNIFORMS ........................................................................................................................... 2 D. PLAIN CLOTHES/ SWORN PERSONNEL ................................................................... 11 E. INSPECTIONS ................................................................................................................... 11 F. LINE INSPECTIONS OF UNIFORMS ........................................................................... 11 G. FLORIDA DRIVERS LICENSE VERIFICATION PROCEDURES ........................... 11 H. MONTHLY LINE INSPECTIONS REPORT AND ROUTING ................................... 12 I. FOLLOW-UP PROCEDURES FOR DEFICIENCY AND/OR DEFICIENCIES ....... 12 J. POLICY STANDARDS/EXPLANATION OF TERMS ................................................. 12 K. GROOMING ....................................................................................................................... 25 Appendix -

The Makers Issue

RHODE ISLAND'S OCEAN AND COASTAL MAGAZINE VOL 14 NO 1 SPRING/SUMMER 2021 41°N THE MAKERS ISSUE A PUBLICATION OF RHODE ISLAND SEA GRANT & THE COASTAL INSTITUTE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF RHODE ISLAND41˚N spring • A /SEAsummer GRANT 2021 INSTITUTIONFC FROM THE EDITOR 41°N EDITORIAL STAFF Monica Allard Cox, Editor Judith Swift Alan Desbonnet Meredith Haas Amber Neville ART DIRECTOR Ernesto Aparicio PROOFREADER Lesley Squillante MAKING “THE MAKERS” PUBLICATIONS MANAGER Tracy Kennedy not wanting the art of quahog tong making to be “lost to history,” Ben Goetsch, Rhode Island Coastal Resources Management Council COVER aquaculture coordinator, reached out to us a while ago to ask if we Portrait of Ned Miller by Jesse Burke would be interested in writing about the few remaining local craftsmen sup- ABOUT 41°N plying equipment to dwindling numbers of quahog tongers. That request 41° N is published twice per year by the Rhode led to our cover story (page 8) as well as got us thinking about other makers Island Sea Grant College Program and the connected to the oceans—like wampum artists, salt makers, and boat Coastal Institute at the University of Rhode builders. We also looked more broadly at less tangible creations, like commu- Island (URI). The name refers to the latitude at nities being built and strengthened, as we see in “Cold Water Women” which Rhode Island lies. (page 2) and “Solidarity Through Seafood” (page 36). Rhode Island Sea Grant is a part of the And speaking of makers, we want to thank the writers and photographers National Oceanic and Atmospheric Adminis- who make each issue possible—many are longtime contributors whose tration and was established to promote the names you see issue after issue and you come to know through their work. -

ADDENDUM (Helps for the Teacher) 8/2015

ADDENDUM (Helps for the teacher) 8/2015 Fashion Design Studio (Formerly Fashion Strategies) Levels: Grades 9-12 Units of Credit: 0.50 CIP Code: 20.0306 Core Code: 34-01-00-00-140 Prerequisite: None Skill Test: # 355 COURSE DESCRIPTION This course explores how fashion influences everyday life and introduces students to the fashion industry. Topics covered include: fashion fundamentals, elements and principles of design, textiles, consumerism, and fashion related careers, with an emphasis on personal application. This course will strengthen comprehension of concepts and standards outlined in Sciences, Technology, Engineering and Math (STEM) education. FCCLA and/or DECA may be an integral part of this course. (Standards 1-5 will be covered on Skill Certification Test #355) CORE STANDARDS, OBJECTIVES, AND INDICATORS Performance Objective 1: Complete FCCLA Step One and/or introduce DECA http://www.uen.org/cte/facs_cabinet/facs_cabinet10.shtml www.deca.org STANDARD 1 Students will explore the fundamentals of fashion. Objective 1: Identify why we wear clothes. a. Protection – clothing that provides physical safeguards to the body, preventing harm from climate and environment. b. Adornment – using individual wardrobe to add decoration or ornamentation. c. Identification – clothing that establishes who someone is, what they do, or to which group(s) they belong. d. Modesty - covering the body according to the code of decency established by society. e. Status – establishing one’s position or rank in comparison to others. Objective 2: Define terminology. a. Common terms: a. Accessories – articles added to complete or enhance an outfit. Shoes, belts, handbags, jewelry, etc. b. Apparel – all men's, women's, and children's clothing c. -

CLOTHING and ADORNMENT in the GA CULTURE: by Regina

CLOTHING AND ADORNMENT IN THE GA CULTURE: SEVENTEENTH TO TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY BY Regina Kwakye-Opong, MFA (Theatre Arts) A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology, Kumasi, in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN AFRICAN ART AND CULTURE Faculty of Art College of Art and Social Sciences DECEMBER, 2011 © 2011 Department of General Art Studies i DECLARATION I hereby declare that this submission is my own work towards the PhD degree and that to the best of my knowledge, it contains no material previously published by another person nor material which has been accepted for the award of any other degree of the University, except where due acknowledgement has been made in the text. Student‟s Name Regina Kwakye-Opong ............................. .............................. Signature Date Certified by (1st Supervisor) Dr. Opamshen Osei Agyeman ............................ .............................. Signature Date Certified by (2nd Supervisor) Dr. B.K. Dogbe ............................... ................................... Signature Date Certified by (Head of Department) Mrs.Nana Afia Opoku-Asare ................................... .............................. Signature Date i ABSTRACT This thesis is on the clothing components associated with Gas in the context of their socio- cultural functions from the seventeenth to the twenty-first century. The great number of literature on Ghanaian art indicates that Ghanaians including the Ga people uphold their culture and its significance. Yet in spite of the relevance and indispensable nature of clothing and adornment in the culture, researchers and scholars have given it minimal attention. The Ga people‟s desire to combine their traditional costumes with foreign fashion has also resulted in the misuse of the former, within ceremonial and ritual contexts. -

Jewish North African Head Adornment: Traditions and Transition

Jewish North African head adornment: Traditions and Transition Garments, head and foot apparel and jewellery comprise the basic clothing repertoire of man. These vestments are primarily dictated by the wearer's climate and environs and, further, reflect the wearer's ethnic affiliation, social and familial status. Exhibitions and museum collections offer a glimpse into the rich variety of headgear characteristic of diaspora Jews: decorated skuU-caps; headbands and head ornaments; turbans and head scarves, as well as shawls and wraps that covered the body from head to foot. Headdresses exist from Europe, Central Asia, Irán, Iraq, Kurdistan, Yemen, the Balkans and, as shall be focused upon in this text, North África. The head apparel and omamentation under discussion in this article were crafted primarily during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. However, it must be noted that Jewish garments and head apparel are known to reflect age-old cultural traditions. The artistic assemblage of head adomments was not, however, uniquely Jewish. The design repertoire of eastern Jewish headdresses was given inspiration also from the Muslim environment. Both populations, in continual fear of idolatry, tumed to symbols rich in hidden meanings and to colours ripe with magical properties. The adornments under consideration here were those worn by the Jewish populace during both ceremonial and festive occasions. Festive garb, including omamented headgear, were used in ceremonies of the life cycle ^ and on Jewish holidays ^. Undoubtedly the most exquisite items were worn by the bride and groom on their wedding day. The Song of Songs 3:11 reflects upon the age oíd custom of head adornment: «Go forth, O daughters of Zion, and behold King Solomon with the crown with which his mother crowned him on the day of his wedding...»». -

SCHOOLS of LOGIC and RHETORIC Uniforms Students Are Required to Purchase One Set of the Formal Uniform Pieces; All Other Pieces Are Optional

SCHOOLS OF LOGIC AND RHETORIC Uniforms Students are required to purchase one set of the formal uniform pieces; all other pieces are optional. * Unless otherwise noted, all uniform pieces, must be purchased from Land's End or Educational Outfitters As stated in the handbook, Eagle Ridge Academy maintains an official standard of dress, complete with a school uniform that must be worn every day in order to encourage students to think of their attire as an aspect of their work, to eliminate self-consciousness and social competition, and to foster a sense of identity. The uniform is to be worn at all times during the school day. Formal uniform is required on formal uniform days, on specified field trips, and on special occasions. Required Uniform Pieces (also formal uniform approved items) Top Options: Headwear: • Shirt: long-sleeved white Oxford (tucked in) OR white • Hijab or headscarves in black, white, gray or burgundy pinpoint princess blouse (logo optional) Note: all (solid color with no pattern or adornment) undershirts must be plain white • Tie: burgundy (required with Oxford shirt) Note: all Note: Hats and caps may not be worn during the school undershirts must be plain white day as they are not considered part of the school uniform. • **Optional formal dress pieces: Note: white Oxford shirt or white pinpoint princess blouse must be worn Footwear: under these items • Socks: black, white, or gray (solid color with no o Cardigan: burgundy (logo optional) pattern); if visible anklet or knee high • o V-neck sweater: burgundy (logo optional) Tights: solid color with no pattern; black, white, gray or burgundy Note: Leggings are not part of the formal o Sweater vest: burgundy (logo optional) Bottom Options: dress uniform. -

Fashion Text Book

Fashion STUDIES Text Book CLASS-XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Preet Vihar, Delhi - 110301 FashionStudies Textbook CLASS XII CENTRAL BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110 301 India Text Book on Fashion Studies Class–XII Price: ` First Edition 2014, CBSE, India Copies: "This book or part thereof may not be reproduced by any person or agency in any manner." Published By : The Secretary, Central Board of Secondary Education, Shiksha Kendra, 2, Community Centre, Preet Vihar, Delhi-110301 Design, Layout : Multi Graphics, 8A/101, W.E.A. Karol Bagh, New Delhi-110005 Phone: 011-25783846 Printed By : Hkkjr dk lafo/ku mísf'kdk ge] Hkkjr ds yksx] Hkkjr dks ,d lEiw.kZ 1¹izHkqRo&laiUu lektoknh iaFkfujis{k yksdra=kkRed x.kjkT;º cukus ds fy,] rFkk mlds leLr ukxfjdksa dks% lkekftd] vkfFkZd vkSj jktuSfrd U;k;] fopkj] vfHkO;fDr] fo'okl] /eZ vkSj mikluk dh Lora=krk] izfr"Bk vkSj volj dh lerk izkIr djkus ds fy, rFkk mu lc esa O;fDr dh xfjek vkSj 2¹jk"Vª dh ,drk vkSj v[kaMrkº lqfuf'pr djus okyh ca/qrk c<+kus ds fy, n`<+ladYi gksdj viuh bl lafo/ku lHkk esa vkt rkjh[k 26 uoEcj] 1949 bZñ dks ,rn~ }kjk bl lafo/ku dks vaxhÑr] vf/fu;fer vkSj vkRekfiZr djrs gSaA 1- lafo/ku (c;kyhloka la'kks/u) vf/fu;e] 1976 dh /kjk 2 }kjk (3-1-1977) ls ¶izHkqRo&laiUu yksdra=kkRed x.kjkT;¸ ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA 2- lafo/ku (c;kyhloka la'kks/u) vf/fu;e] 1976 dh /kjk 2 }kjk (3-1-1977) ls ¶jk"Vª dh ,drk¸ ds LFkku ij izfrLFkkfirA Hkkx 4 d ewy dÙkZO; 51 d- ewy dÙkZO; & Hkkjr ds izR;sd ukxfjd dk ;g dÙkZO; gksxk fd og & (d) lafo/ku -

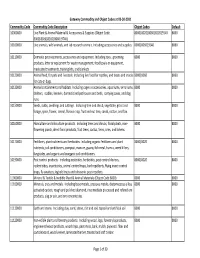

Commodity Codes with Object Codes

Gateway Commodity and Object Codes at 03‐30‐2021 Commodity Code Commodity Code Description Object Codes Default 10000000 Live Plant & Animal Material & Accessories & Supplies (Object Code 8000|8020|8060|8105|9140 8060 8000|8020|8105|8060|9740) 10100000 Live animals, wild animals, and lab research animals. Including accessories and supplies. 8000|8060|9140 8060 10110000 Domestic pet treatments, accessories and equipment. Including toys, grooming 8000 8000 products, litter or equipment for waste management, food bowls or equipment, medicated treatments, training kits, and blankets 10120000 Animal feed, for pets and livestock. Including live food for reptiles, and treats and snacks 8000|8060 8060 for cats or dogs. 10130000 Animal containment and habitats. Including cages or accessories, aquariums, terrariums, 8000 8000 shelters, stables, kennels, domesticized pet houses and beds, carrying cases, and dog runs. 10150000 Seeds, bulbs, seedlings and cuttings. Including tree and shrub, vegetable, grass and 8000 8000 forage, spice, flower, cereal, fibrous crop, fruit and nut tree, carob, cotton, and flax. 10160000 Floriculture and silviculture products. Including trees and shrubs, floral plants, non‐ 8000 8000 flowering plants, dried floral products, fruit trees, cactus, ferns, ivies, and lichens. 10170000 Fertilizers, plant nutrients and herbicides. Including organic fertilizers and plant 8000|8020 8000 nutrients, soil conditioners, compost, manure, guano, fish meal, humus, weed killers, fungicides, and organic and inorganic soil conditioners. 10190000 Pest control products. Including pesticides, herbicides, pest control devices, 8000|8020 8000 rodenticides, insecticides, animal control traps, bird repellents, flying insect control traps, fly swatters, leghold traps and ultrasonic pest repellers. 11000000 Mineral & Textile & Inedible Plant & Animal Materials (Object Code 8000) 8000 8000 11100000 Minerals, ores and metals. -

Daughters of Sarah: a Scriptural Treatise on the Adornment and Work of Christian Women

Abilene Christian University Digital Commons @ ACU Stone-Campbell Books Stone-Campbell Resources 1938 Daughters of Sarah: A Scriptural Treatise on the Adornment and Work of Christian Women Dennis Kellogg Mrs. Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books Part of the Biblical Studies Commons, Christian Denominations and Sects Commons, Christianity Commons, Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, Ethics in Religion Commons, Gender and Sexuality Commons, Practical Theology Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Kellogg, Dennis Mrs., "Daughters of Sarah: A Scriptural Treatise on the Adornment and Work of Christian Women" (1938). Stone-Campbell Books. 191. https://digitalcommons.acu.edu/crs_books/191 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Stone-Campbell Resources at Digital Commons @ ACU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Stone-Campbell Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ ACU. DAUGHTERS of SARAH "Even as Sarah obeyed Abraham, calling him lord, whose daugh ters ye are as long as ye do well . ." (1 Pet. 3:6). A Scriptural Treatise on the Ador nment and Work of Christian Women. By MRS. DENNIS KELLOGG Farm ers Bra nch , Texas TABLE OF CONTENTS Title Page To a Great-Souled Woman 2 Introduction 3 Foreword 4 Outward Adornment 5 Inward Adornment 8 Work Pertaining to the Home . 11 Work Pertaining to the Christian Life in General 15 Work Pertaining to the Church .... ... 19 Note to Reader .. .. .. .... .. .. ... 22 Note: All scripture quotations are from King James Version, except where otherwise indicated . DAUGHTERS of SARAH "Even as Sarah obeyed Abraham , calling him lord, whose daughters ye are as lonq as ye do we ll . -

SCHOOLS of GRAMMAR Uniforms Students Are Required to Purchase One Set of the Formal Uniform Pieces; All Other Pieces Are Optional

SCHOOLS OF GRAMMAR Uniforms Students are required to purchase one set of the formal uniform pieces; all other pieces are optional. * Unless otherwise noted, all uniform pieces, must be purchased from Land's End or Educational Outfitters As stated in the handbook, Eagle Ridge Academy maintains an official standard of dress, complete with a school uniform that must be worn every day in order to encourage students to think of their attire as an aspect of their work, to eliminate self- consciousness and social competition, and to foster a sense of identity. The uniform is to be worn at all times during the school day. Formal uniform is required on formal uniform days, on specified field trips, and on special occasions. Formal Dress Requirements (may be worn daily): Top Options: Sock Options: • Burgundy or white polo with logo (banded or not) Short • White, black, or gray (solid color with no logos, pattern or or Long Sleeve adornment – knee high, crew, or anklets)* Note: All undershirts must be plain white. Long sleeve Note: Leggings are not part of the formal dress uniform. shirts cannot be worn under short sleeve uniform pieces. Non-banded shirts must be tucked in at all times. Bottom Options: Shoes: • Plaid skort (hemmed no higher than 2’ above knee • Black or brown dress shoes* • Plaid jumper Note: The heel height must not exceed one inch. • Khaki Pants • Tights: black, gray, white, or burgundy (solid color, no adornments)* Casual Uniform Pieces (if not wearing Formal Dress): Top Options (logo only required on specified items): Socks: -

A Study of Beads and Adornment in Contemporary Krobo Society Jordan Ashe SIT Study Abroad

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Spring 2012 Progression of Aesthetic: a Study of Beads and Adornment in Contemporary Krobo Society Jordan Ashe SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the African Languages and Societies Commons, Art and Design Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Place and Environment Commons Recommended Citation Ashe, Jordan, "Progression of Aesthetic: a Study of Beads and Adornment in Contemporary Krobo Society" (2012). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1248. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1248 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. School for International Training Study Abroad – Ghana: Social Transformation and Cultural Expression Spring 2012 Progression of Aesthetic: a Study of Beads and Adornment in Contemporary Krobo Society Jordan Ashe [Spelman College] Project Advisor: Dr. R.T. Ackam Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST), Kumasi Academic Director: Olayemi Tinuoye Abstract 1. Title : Progression of Aesthetic: a Study of Beads and Adornment in Contemporary Krobo Society 2. Author: Jordan Ashe ( [email protected] ; Spelman College) 3. Objective: The objective of this project was three-fold: i. To learn the traditional and contemporary practices of Krobo style and adornment, ii. To examine the traditional and contemporary importance of beads in Krobo: what was their traditional significance and use as opposed to now? What is the significance of beads today? iii. -

Christian Dress & Adornment

iblical 10 erspectives Christian Dress & Adornment by Samuele Bacchiocchi Essays by Laurel Damsteegt and Hedwig Jemison iblical erspectives 4990 Appian Way Berrien Springs Michigan 49103, USA BOOKS BY THE SAME AUTHOR THE CHRISTIAN AND ROCK MUSIC is a timely symposium that defines the biblical principles to make good musical choices. THE SABBATH UNDER CROSSFIRE refutes the common arguments used to negate the continuity and validity of the Sabbath. IMMORTALITY OR RESURRECTION? unmasks with compelling Biblical reason- ing the oldest and the greatest deception of all time, that human beings possess immortal souls that live on forever. THE MARRIAGE COVENANT is designed to strengthen your Christian home through a recovery of those biblical principles established by God to ensure happy, lasting, marital relationships. THE ADVENT HOPE FOR HUMAN HOPELESSNESS offers a scholarly, and comprehensive analysis of the biblical teachings regarding the certainty and imminence of Christ’s Return. FROM SABBATH TO SUNDAY presents the results of a painstaking research done at a Vatican University in Rome on how the change came about from Saturday to Sunday in early Christianity. THE SABBATH IN THE NEW TESTAMENT summarizes Bacchiocchi’s exten- sive research on the history and theology of the Lord’s Day and answers the most frequently asked questions on this subject. WINE IN THE BIBLE shows convincingly that the Bible condemns the use of alcoholic beverages, irrespective of the quantity used. CHRISTIAN DRESS AND ADORNMENT examines the Biblical teachings regarding dress, cosmetics, and jewelry. An important book designed to help Christians dress modestly, decently, and reverently. DIVINE REST FOR HUMAN RESTLESSNESS offers a rich and stirring theo- logical interpretation of the relevance of Sabbathkeeping for our tension-filled and restless society.